[Editor’s Note: The following is from a pamphlet I recently obtained while visiting the Roger Williams National Memorial, which is owned and operated by the National Park Service of the U.S. Department of the Interior. The National Memorial is located at 282 North Main Street in Providence.]

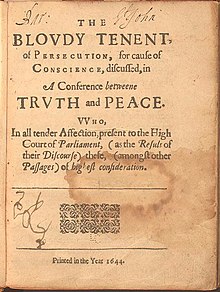

“. . . that no civil magistrate, no King, more Caesar, have any power over the souls or consciences of their subjects, in the matters of God and the crown of Jesus.” Roger Williams, The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution.

Through word and act Roger Williams fought for the idea that religion must not be subject to state regulation but should be a matter of individual conscience. Americans now take this for granted, but most people of his time condemned such ideas as naive and dangerous. They believed religious freedom and civil order could not coexist. Williams extended his defense of individual conscience to American Indians, respecting their rights and condemning imposed Christianity. As the founder of Rhode Island, he put his beliefs into practice, giving “shelter for persons distressed of conscience.”

Defender of Conscience

Roger Williams’s academic promise convinced eminent jurist Sir Edward Coke to help him acquire an excellent education. Born in London in 1603, and trained as an Anglican clergyman, he increasingly sympathized with Puritans, who believed the Church of England had not made a clean break with Catholicism. The Puritans’ options were to risk jail or worse by trying to reform in England or move to more tolerant Holland. In 1629 a third choice arose: Some Puritans founded the Massachusetts Bay Colony and elected John Winthrop governor. They sailed the next year, founding Boston and several other settlements.

Rejecting the Middle Way Roger and his wife Mary sailed with another group in 1631. On arrival he was noted by Winthrop as “a godly minister,” but the two soon clashed. Williams became a separatist, a Puritan wanting to leave the Anglican Church, and believed that not separating from the established church was “middle walking” and “halting between Christ and antichrist.” But the colony refused to take so radical a step. Other issues set Williams at odds with Puritans. He rejected civil jurisdiction over “First Table” laws (the first four of the Ten Commandments), which were matters of individual conscience. He disputed English charters that took land from American Indians. He denounced “hireling” ministers paid from taxes and civil oaths taken in God’s name. Massachusetts Bay finally sentenced the troublesome minister to deportation; he fled the colony to avoid arrest.

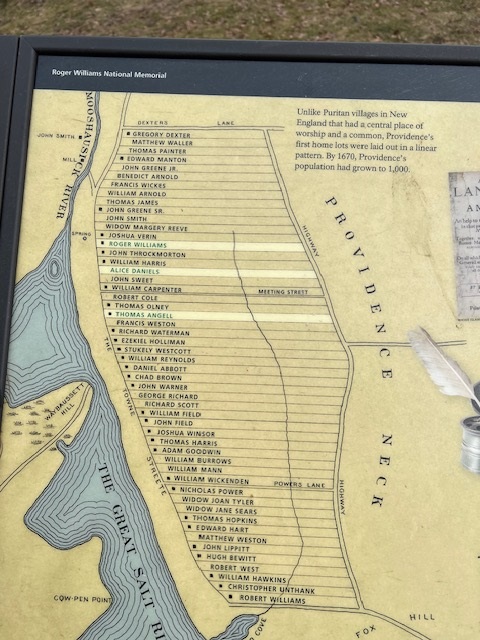

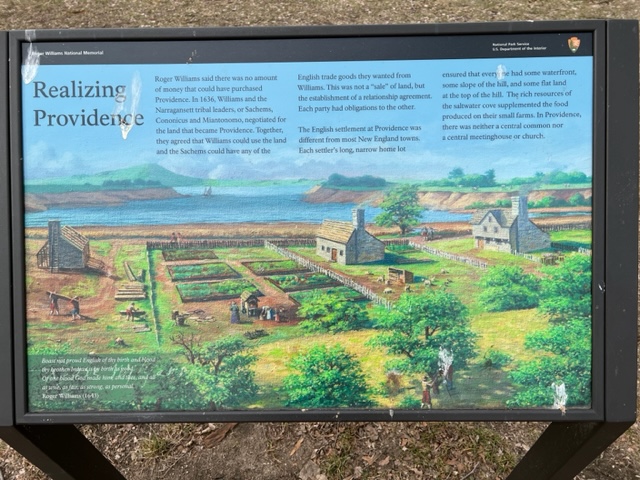

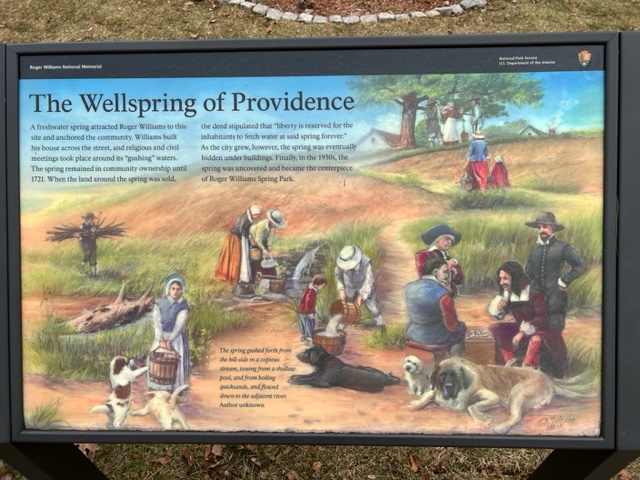

The Narragansett deeded Williams land in 1636 for a colony at the headwaters of Narragansett Bay that he named Providence after “God’s merciful Providence unto me in my distress.” After he was joined there by family and a few friends, the settlers formally agreed to “hold forth Liberty of Conscience,” making laws “only in civill things.” But he had to divide his energies between the new colony—soon called Rhode Island—and other developments. Though he remained an outcast, he was valuable to Massachusetts as a negotiator. When rumors spread that the Narragansett would ally themselves with the Pequot against the English, Governor Winthrop asked Williams to meet with the Narragansett to prevent the alliance. Williams succeeded, even getting them to help the English. The ensuing war of 1637-38 greatly reduced the Pequot population. In coming decades Williams repeatedly was asked to negotiate with American Indians on behalf of the colony that had expelled him.

Williams’s beliefs about freedom of conscience were stated in his 1644 tract, The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution

Williams remained busy, establishing a trading post south of Providence around 1637 and cofounding the first Baptist Church in North America in 1638. By 1643 the towns of Portsmouth, Newport, and Warwick had also been established in the area by fellow dissenters. That year Williams returned to England to secure a charter for the colony, and in 1651, trying to hold Rhode Island together, he traveled to England again to defend the charter against another grant that threatened to split the colony.

In his later years Williams’s health deteriorated. In 1676 he was “near destitute,” he said, from a lifetime committed to the colony without trying to accumulate land or a fortune—the first order of business for many prominent colonists. He had sold his trading post—his one dependable source of income—to finance his 1651 trip to London to defend the colony. Williams died in 1683, his wife Mary having died several years before.

The Dream Realized In his final year Williams wrote a letter pleading with Rhode Island citizens to put away “heats and hatreds” and “Submit to Government.” He was content with the colony charter. More than any other, it set into law the freedom for the “Souls of Men” he had sought. He found the goal a self-evident truth he spent his life trying to make others see. Forty years earlier he wrote: “a man may clearly discern with his eyes and as it were touch with his finger, that according to the verity of holy scripture men’s consciences ought in no sort to be violated, urged, or constrained.” His ideas were addressed, though less vividly, 100 years later in the U.S. Constitution’s First Amendment. In that document this complex man’s abiding passion for freedom of conscience found protection in the laws of the land.

Religious Conflict in England

England in the 1500s demanded religious conformity, forbidding “unlawful assemblies. . . under color or pretense of any exercise of religions, contrary to her majesty’s said laws. Catholics and radical Puritans who refused to conform even outwardly met persecutions as dissenters—public humiliation, torture and sometimes death. Stuart monarchs of the early 1600s also opposed unorthodoxy, but early migrations to the new world had begun and the Crown and Parliament gave colonies more latitude. Many Puritans chose to emigrate.

Roger Williams arriving at Providence. He was allowed to establish Providence by Narragansett chieftains (Rhode Island School of Design Museum)

In 1642 conflicts between the Stuarts and Parliament led to the English Civil War, with Puritans taking Parliament’s side. Roger Williams’s views were too extreme for both sides. On a visit to London in 1644, he published The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution, calling for religious freedom for all” “Paganish, Jewish, Turkish, or Antichristian.” Parliament ordered all copies burned. By 1653 independent Puritan Oliver Cromwell ruled England. Independents believed each congregation should order its affairs with no outside interference. Williams invoked England’s example, urging Massachusetts to allow its churches more freedom.

After the monarchy was restored in 1660, Anglicanism was again the national religion, and one style of conformity replaced another. But dissent across the Atlantic was less feared. In 1663 Charles II granted Rhode Island a charter confirming that no one would be “molested, punished . . . or called in question” for differing religious opinions. England’s 1689 Act of Toleration moved in that direction, allowing all Protestant worship recognizing the Holy Trinity. Public worship by Catholics and other religious groups was still banned.

Roger Williams, Indian Rights, and Religious Freedom

Roger Williams remained close with the Narragansett sachems (leaders) who deeded land to him in 1636. “. . . in consideration of the many kindnesses and services he hath continually done for us . . . we [the Narragansett] do freely give unto him [Roger Williams] all that land from those rivers reaching to Pawtuxet River.” As payment for the land, Williams let Canonicus take what he wished from his trading post. Shell bead strings [called Wampum] were used ceremonially and as a medium of exchange.

In 1643 an enemy tribe [the Mohegans in southeastern Connecticut], conspiring with the English [Massachusetts and Connecticut Puritans], murdered one of the sachems, Miantonomo. Williams and the other sachem, Canonicus, were lifelong friends.

To Know a People

The Algonquian-speaking tribes that Roger Williams came to know so well had long prospered in southeastern New England. When the Puritans first came to their homeland, the tribes already had contact with Europeans, from Basque fishermen to traders and. explorers like Verrazano. They were ready to deal with English settlers as equals. The region’s tribes—Pequot, Wampanoag, and Narragansett—were migratory, their economy based on agriculture, hunting, and gathering. They moved with the yearly cycles to establish places to best exploit seasonal resources. Spring found dispersed groups settled near waterways in coastal areas, living in circular wigwams made of bent saplings covered with woven reed mats, hides, or bark. They harvested fish and shellfish, trapped ducks and geese, hunted and gathered plant foods. They periodically burned large areas to create meadows to attract deer for meat and to clear fields for planting maize, beans, and squash. The fire-resistant trees produced an abundant harvest of nuts in the fall. During winter they gathered inland in sheltered valleys. There several families lived in long houses built like wigwams. They relied on fresh shellfish, stored food, and hunting to survive the cold, lean months.

A Fragile Bond Roger Williams spent a lifetime trying to forge closer ties with the Wampanoag and especially the Narragansett tribes. The Narragansett deeded the land to him for Providence and, with the Wampanoag, helped the colony in its early months. Thereafter William’s complex relationship with American Indians included defending their rights, studying them as an anthropologist and dealing with them as a diplomat. His A Key into the Language of America (1643) alternated translated Narragansett words with related observations of the tribe’s culture. For example, Uppaquontup (the head) and wesheck (hair) preceded the note that “some cut their haire round, and. some as low and as short as the sober English.” His religious tract, Christenings make not Christians, condemned mass American Indian conversions because an American Indian’s conscience should be as inviolate as a European’s. He preached the gospel and lived the Christian life as an example to them, but he believed they had the right to worship as they wished.

Williams admired the American Indians but never romanticized them, believing they could be both noble and “insolent.” And he was an Englishman first of all: He headed a militia during King Philip’s War, and then presided over the selling of American Indian slaves to raise money for English families who lost their homes in the war. For his time, Williams had extraordinary respect for tribal rights. When settlers seized American Indian land, Williams said that tribes had as strong a sense of land ownership as the English. He also ensured the American Indian deed to Rhode Island was interpreted literally when some settlers argued that riverbank grazing rights meant rights to the entire region. Perhaps the dying request of Narragansett sachem Canonicus best shows Williams’s relationship with the tribes. Canonicus asked that Williams attend his funeral and that he be buried in the cloth Williams had given him.

Williams championed American Indian rights, but—unlike in his fight for religious freedom—this bore little fruit. By 1675 the rich American Indian cultures of 1620 were reeling from war and disease, and Europeans would take virtually all of their lands. But Roger Williams led in helping these Europeans understand the first settlers of North America.

Rhode Island: Refuge for Belief

Rhode Island lived up to its charter allowing all forms of worship and sheltering religious fugitives like Anne Hutchinson, a fellow exile from Massachusetts. Descendants of Jewish settlers expelled from Spain and Portugal in the 1400s came to Rhode Island in search of religious freedom. When some of the colonists questioned Jews becoming citizens, the General Assembly said, “they may expect as good protection here as any stranger residing among us.”

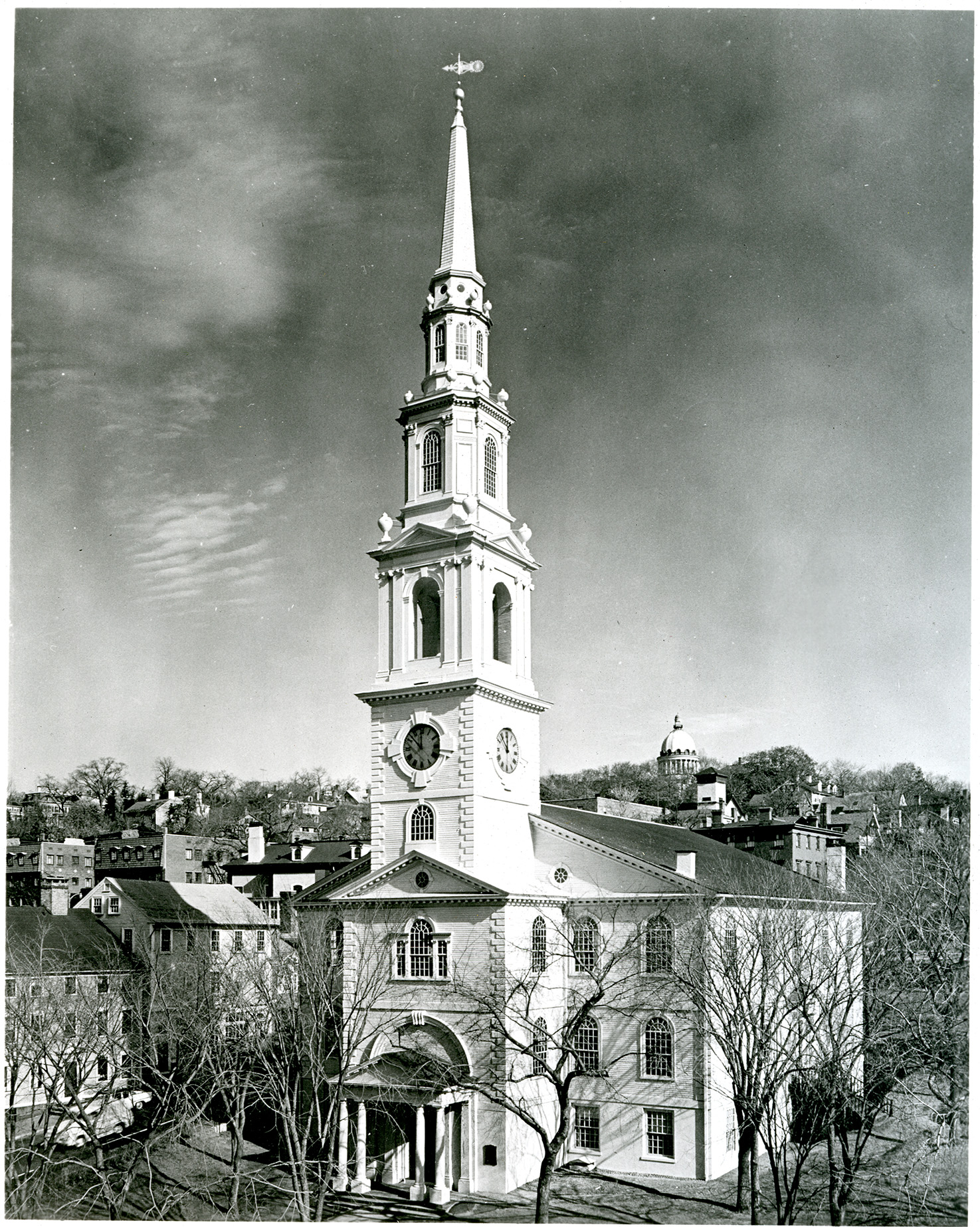

Baptists, barred from Massachusetts, were welcomed also. In Providence they could attend the first Baptist church in America, which had been gathered by Roger Williams. He soon left the group, coming to believe no earthly church could fit the “first and ancient pattern” of the New Testament, at least until the return of Christ.

The First Baptist Meeting House, near Roger Williams National Memorial, represents one of many active faiths in Providence. It is the oldest Baptist Church in America. Located at the corner of North Main and Waterman Street (Providence Public Library Digital Collections)

Yet Roger Williams did not casually accept all faiths. At age 70 he rowed 25 miles from Providence to Newport to debate Quakers. He mistrusted a religion that relied more on “inner light” than on the New Testament. But Quakers in Rhode Island were never punished for their religious beliefs or practices, whereas in Massachusetts some Quakers were hanged. Rhode Island’s first charter said that as long as they obeyed the civil laws, all Rhode Island citizens could “walk as their consciences persuade them.”

Williams likened Rhode Island to “many a Hundred Souls in one ship.” The captain should punish those who “refuse to obey the common laws and orders of the ship,” but “none of, the Papists, Protestants, Jews, or Turks should be forced to come to the Ship’s Prayers or Worship; nor, secondly, compelled from their own particular Prayers or Worship, if they practice any.” This compelling image of the state’s role would set the pattern for a nation.