I have been thinking an awful lot about Russell Smith lately. I have pondered the life of this early nineteenth century ship carpenter, thinking about the unimaginable trials and tribulations that were “part and parcel” to his life, and wondering how he got through it all.

Russell Smith was born sometime around 1794 in the farmhouse of his parents Benjamin and Mary Smith. His birthplace was located at the intersection of the Boston Post Road and Stony Lane. (The original building was torn down in the 1940s and the spot is now occupied by the North Kingstown Post Office.)

Smith was an educated man, as his extant copious writings attest. And he was also a gifted carpenter who worked primarily in Wickford, building schooners, sloops, and brigs for both the Holloway and C & B Spink Shipyards. He kept detailed notes on all this work in a ledger book, noting hours worked on whatever sailing vessel was being constructed at the time, as well as time spent building barns and farm implements, repairing oxcarts, dynamiting and digging wells, grafting fruit trees, cutting firewood and the like. In short, he would do anything a man with a family might do back then to make ends meet.

Smith had married a local gal, Phebe Mann. In about 1816, he built a fine new house on some of his father’s land fronting on Stony Lane, and he began a family with his new bride. Soon, a son, Benjamin, and two daughters Mary and Catherine, were born. Russell Smith’s life was good—hard perhaps, but good nonetheless.

Sadly, Russell and Phebe’s good fortune took a turn for the worse. Their children started dying. First, young Benjamin passed over to the other side and then the light of Russell’s life, daughter Mary, died as well. The double blow overwhelmed Russell with grief. As a parent myself I cannot imagine any emotional pain greater than having to bury your own child, never mind two of them in a short span. Crippling depression suddenly overwhelmed Russell. He turned towards alcohol as a way to cope with his losses, to anesthetize himself against the very personal pain he was suffering.

Russell’s family, strong men and women of Quaker and Baptist stock, refused to stand by and allow Russell to destroy himself in his grief. They knew Russell still had a wife and a remaining daughter to support and that he was a good man.

Russell’s father, Benjamin, and his brother, Harris, performed the nineteenth century equivalent of an “intervention.” Benjamin and Harris went out one night and rounded up Russell, perhaps at a local tavern, and hauled him back to his home on Stony Lane. Father and brother then manacled one of Russell’s legs and chained him to the floor of his front parlor. They were insisting that Russell face his demons head on without the benefit of a bottle in his hand. They left him there with a simple table and chair, perhaps a sturdy metal pail in the corner. They left one more thing, above all others, that saved this once exemplary good man: a ream of paper and a pen and ink.

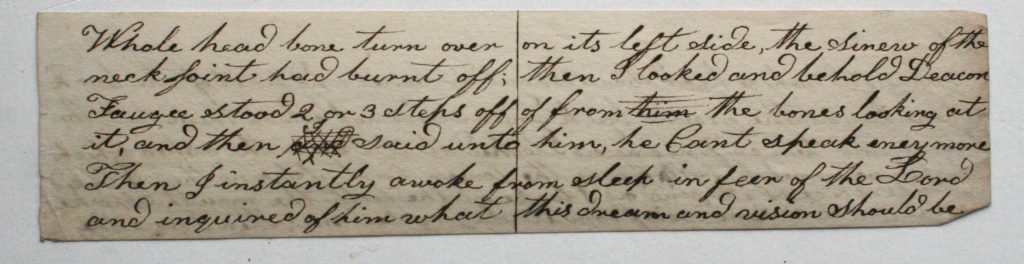

This excerpt from Russell Smith’s writing indicates his disturbed frame of mind. It says: “Whole head bone turn over on its left side, the sinew of the neck joint had burnt off; then I looked and behold Deacon Faugee stood 2 or 3 steps off of from the bones looking at it, and the said unto him, he can’t speak any more. Then I instantly awoke from sleep in fear of the Lord and inquired of him what this dream and vision should be.” (Tim Cranston)

Russell’s father and brother would come by often to check on Russell, to feed him and attend to his needs. As can be imagined, Russell was angry at first. Russell’s niece, Hattie Smith, wrote in her diary, “I went up to Uncle Russell’s with Grandfather, and Grandfather stopped in the front entry and told me to hand him (Russell) a cake of gingerbread. I did so. I presume it wouldn’t have done for Grandfather to have gone so near him then . . . .” Hattie realized that to avoid a verbal confrontation, she must hand the gingerbread to her uncle. The sight she witnessed was emblazoned in her memory for her life. “I remember when I was a little girl, seeing him chained to his front room floor,” Hattie recalled.

An angry Russell took hold of the only thing left to him, the paper and pen, and began to write his way through the delirium and derangement in which he found himself. His earliest writings hint at his state of mind as he battled with his demons, and the “demon drink”. The papers he wrote on were “fully covered,” as Hattie remembers, with writings that bordered upon nonsensical, dreams and visions recalled in intricate detail. They were ramblings and rages, punctuated with occasional pleas to his father for release from his captivity. Slowly his writings began to make sense, as he climbed out of his personal hell. Hattie writes again remembering seeing him later, “silent, pale, and sober looking.”

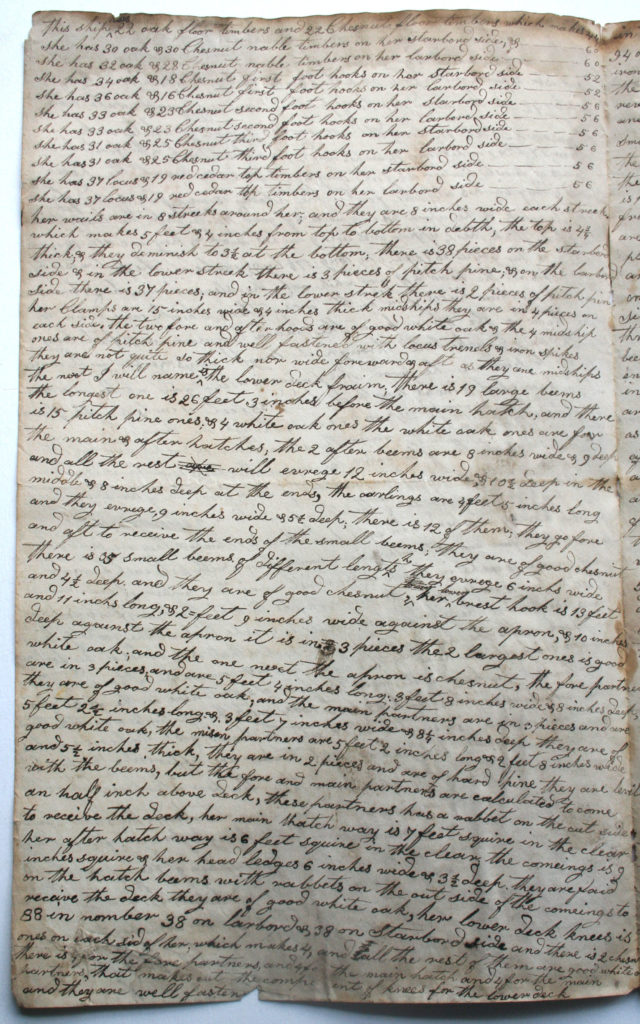

As Russell Smith slowly pulled himself together, he continued to do the only thing he could, the one thing that saved him in fact: he wrote. He wrote lists of the sailing vessels he had helped construct. He even wrote a long and detailed set of instructions, from memory, of exactly how to build a schooner, what wood to use for each portion of the vessel, dimensions needed, where to use spikes versus nails, and how to set the masts. He wrote down remembered songs and poems. In short, Russell wrote himself back from madness.

Eventually, Russell was deemed “cured” and set free by his father and brother. He went about his business, attended to his life, wife, and remaining daughter, and by all accounts was again, as his niece Hattie Smith described him, “an exemplary, good man”. He died in February of 1848 and was buried in the Smith family graveyard located on Stony Lane, between the house of his birth and that of his temporary incarceration. His gravestone is just behind that of his son Benjamin and right next to the grave of his beloved daughter Mary. Mary is in turn buried next to Phebe who followed her husband to heaven some ten years later. Again Hattie’s diary speaks volumes about the connection between Russell and Phebe: “Aunt Phebe used to say after Uncle Russell died, that she didn’t live, she stayed, meaning her lonely life was monotonous, I suppose . . . .”

This page from Russell Smith’s writing shows his detailed directions on building a three-masted schooner, apparently all from memory. His writing is very neat and legible, probably a by-product of his Quaker upbringing (Tim Cranston)

I drive by the circa 1816 house that Russell Smith built on Stony Lane often and I can’t help but think about him and what he lived through. I visit the Smith graveyard from time to time as well and cannot help but note that Russell’s gravestone has fallen over of late, but is propped up now and forever, I expect, by the footstone of his father Benjamin. I can’t think of anything more appropriate than that. Rest in peace Russell Smith, rest in peace.

Bibliography

Diaries of Harriet Smith – unpublished manuscript in private hands whose owner desires to by anonymous

The Russell Smith Papers- unpublished manuscript in private hands whose owner desires to by anonymous

Vital Records – Town of North Kingstown

Land Evidence Records – Town of North Kingstown

[Banner image: Current photograph of the house that Russell Smith built about 1816, on Stony Lane (Tim Cranston)]