“Some things can be done as well as others” … Sam Patch

In the 19th century Rhode Island was the home of two daredevils who achieved fame for their bold acts of daring. The first was Sam Patch who became nationally known as a jumper from staggering water fall heights into rivers below. Patch’s fame was such that President Andrew Jackson named his horse Sam Patch. The other was Benoni Sweet who styled himself as “Professor Benoni Sweet” and received regional acclaim for his feats of death-defying acts on a tight rope. A prior article in this two-part series addressed Benoni Sweet’s career. This article focuses on Sam Patch.

In 1791 Samuel Slater, with the financial backing of Moses Brown and others, built the first water powered loom in the United States at Pawtucket by the falls of the Blackstone River. As such, Pawtucket is said to be the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution in America. Within just a short period of time, water powered factories cropped up all over New England, affording employment for many people, including children.

Initially, farmers sent their children to work in the mills. The children not only missed time spent in school and acting like the children whom they were, they worked in miserable conditions. The farmers began pulling their children out of the mills. Samuel Slater and other mill owners needed to look elsewhere for cheap employment. They found it in the form of children of recent immigrants. One of these children was Sam Patch.

The Patch family hailed originally from northeastern Massachusetts and probably relocated to Pawtucket for employment. Sam was the fifth of six children born to Mayo Greenleaf Patch and Abigail McIntire. The year of Sam’s birth is disputed—some sources say it was 1799 but others claim it was 1807. Most likely, as reported in Sam Patch, the Famous Jumper, by Paul E. Johnson, Sam’s birth was at North Reading Massachusetts in 1799. While his birth date may be in dispute what is certain is the date of Sam’s death, which occurred on November 13, 1829, in a fatal leap into the Genesee River at the upper falls at Rochester, New York.

Sam’s family moved to Pawtucket in 1807 and he eventually went to work in one of the textile mills along the Blackstone River. It was not unusual for young children to work in the mills and while just eight years old, Sam’s pay must have been necessary for the family’s survival. The Patch family, as historian Paul Johnson notes, was dysfunctional. Sam’s father drank too much and was often unemployed.[1] By 1818, Sam’s mother, Abigail Patch, had sued for divorce, then an uncommon act.

Sam progressed in responsibly at the mills, and over time, he was promoted to mule spinner. Life, while employed at the mills was dreary and monotonous, working from daylight to dusk with little time for oneself. One of the few enjoyments for the young mill workers was swimming and jumping in the Blackstone River during their lunch breaks; at this, Sam excelled.

Paul Johnson, in his short biography of Sam Patch upon which this article largely relies, described how falls jumping started in Pawtucket:

Early on, boys began jumping from the bridge into the river below the falls. It was a drop of more than fifty feet, and the bottom was rocky and dangerous. At one spot near the east bank, however, the falls had carved a deep hole, and there the aerated water was, as a local journalist put it, “nearly as soft as an ocean of feathers.” The boys called in “the pot.” In 1805, when the four-story Yellow Mill went up on the east side just below the falls (two stories above road level, two below), the jumpers wasted little time. That year three you men made the astounding eight-foot leap from the peaked roof of the Yellow Mill into the pot. In 1813 the six-story Stone Mill went up on the east side, just below the bridge. In ensuing years, the bravest Pawtucket boys—Sam Patch among them—regularly made a running leap from its flat roof into the pot, a descent of close to one hundred feet.[2]

Johnson also described the craft of falls jumping that the Pawtucket boys developed:

The Pawtucket boys all jumped the same way: feet first, breathing in as they fell; they stayed under water long enough to frighten spectators, then shot up triumphantly to the surface. It was truly dangerous play . . . .[3]

Pawtucket authorities eventually shut down the practice as too dangerous, but not before Sam honed his skills as a falls jumper. And it was only Patch who recognized that there could be fame and money in falls jumping outside of Pawtucket.

When or why Sam Patch left Pawtucket is unknown. One newspaper account suggested that he left to seek glory; but the same account also reported that upon leaving Pawtucket he went to sea.[5] Patch continued to jump but now it was from the topmast of the ships on which he sailed. There are no recorded accounts of his time at sea, but it did not last long. In 1827, he appeared in Paterson, New Jersey, working in a mill as a mule spinner. It was in Paterson where he would achieve fame and receive the title of the “Jersey Jumper.”

The first recorded account was a leap of seventy feet at the Passaic Falls. The jump took place in September 1827 on the same day that the new Forrest Garden outdoor park built by its developer, Tim Crane, was to open across the Clinton Bridge. (A mishap occurred when in the process of moving the preassembled bridge into place one of the roller logs fell from the cliff to the chasm below, causing spectators to gasp.)

Patch meant for his jump to steal the show away from the festivities planned for the day. It was a calculated move on Patch’s part as the festivities were well attended with estimates of from six to ten thousand people attending. Certainly, it was Patch’s largest audience to date.

Historian Paul Johnson described the scene:

It was a straight seventy-foot drop to the water below, and Sam took it in fine Pawtucket style. At the end he brought up his knees, then snapped them straight, drew his arms to his sides, and went into the water like an arrow. Tim Crane and his kidnapped audience stared into the chasm, certain that Sam was dead. But in a few seconds Sam shot to the surface. The crowd cheered wildly as Sam sported in the water, paddled over to Crane’s log roller, took the trail rope between his teeth, and towed it slowly and triumphantly to the shore.[4]

As Johnson notes, Sam’s jump was well received by his audience. He would jump again at Paterson on Independence Day, July 4, 1828, and again fifteen days later. There was a strike at all but two of the mills in Paterson beginning on July 21 and by the time the strike was over in early August many of the strike’s ring leaders were dismissed. Possibly Patch was one of those workers fired as he never jumped in Paterson again. Within days of the strike’s end, however, Patch jumped from the topmast of a ship in Hoboken, New Jersey, on August 6. Other than a jump on July 4, 1829, at Little Falls on the Passaic River, Patch never jumped again in New Jersey.

Niagara Falls and Bridge across Gully from the Basin. Original caption said: “This shows the place where the celebrated Sam Patch jumped from the old tree on the left, down 80 feet to the water.” (New York Public Library Digital Collection)

Patch set his sights for the big time, at Niagara Falls, that tallest and most impressive water fall in all of North America. In 1829 he was invited to jump at Niagara Falls by a promoter who planned a day of festivities in early October, which was to include Patch’s leap.

Patch’s jump and other festivities were scheduled to take place at Niagara Falls on October 6, but Patch arrived late in the evening of October 5—too late to make his scheduled jump the next day. He had been brought to town at the invitation of promoters who planned a variety of events including the blowing up of rocks at the falls as well as having the ship Superior plunge over the falls. The great number of attendees was sure to get lots of newspaper coverage and fame for Sam, not to mention money collected from the audience. His leap had to be rescheduled for October 7, thus providing Patch time he needed to inspect the pool of turbulent waters and its currents below the falls into which he planned to leap.

October 7 was rainy and the ladder he was to climb to reach its platform was dropped by the workmen and damaged. Patch’s leap was to be from a height of about eighty feet, similar to his other leaps in New Jersey. The leap at Niagara was from Goat Island, midway between the Canadian horseshoe falls and the American falls.

Remarkably, the leap was accomplished without a hitch. Patch became convinced that he could successfully jump from even greater heights. Accordingly, he soon announced he would jump again on October 17 from a platform forty to fifty feet higher than that of his first Niagara jump.

On October 17 he sailed from Buffalo, where he was staying at a hotel, to Niagara. During this trip he amused the other passengers with a jump from the ship’s forearm, a leap of about forty to fifty feet above the water. Once at Niagara Falls, he prepared for his big leap. Preparation usually included a significant amount of alcohol consumption as Patch was known for his hard drinking habits. The leap was from the phenomenal height of 125 feet. After a delay due to rain, he made his jump at 4 o’clock that afternoon. It was a successful jump. Patch then set his sights on Rocester and the upper falls on the Genesee River. It would prove to be a fatal decision.

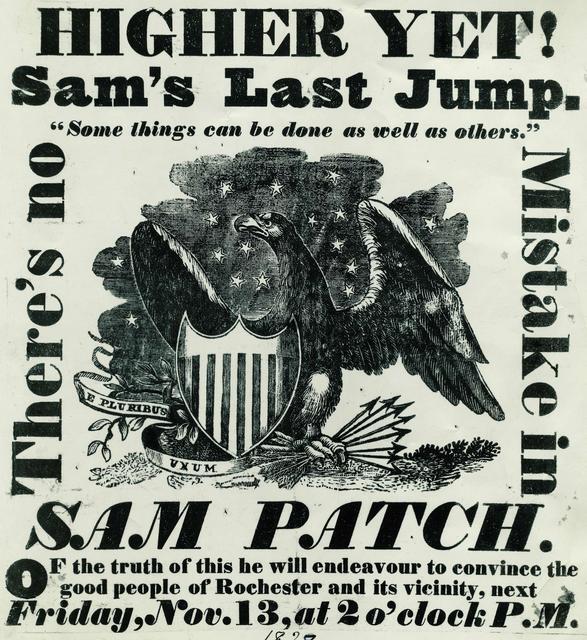

Patch made two leaps at Rochester, the first on November 6 before a crowd estimated to have been between six and eight thousand people. The jump went off without a problem. Now Patch scheduled a second leap for Friday, November 13, and it was well-advertised. It was billed as his last jump, meaning his last jump of the season.

Normally Patch jumped feet first with his arms raised above his head and as he neared the water, he brought his arms by his side. But on his Friday the 13th jump he lost control and on decent his body turned, and he entered the water on his side. It was a fatal error on Patch’s part. It was likely that the impact knocked him unconscious if not killed him outright. If he was only knocked unconscious, he likely died by drowning. Historian Paul Johnson believes Patch was drunk for his last jump. Patch’s body was not recovered until March of the following year, seven miles down river from where he made his jump.

Today, in a quest to be noticed people sometimes put themselves at great risk performing dangerous stunts to be posted on social media for their oft cited fifteen minutes of fame. Sam Patch too put himself at great risk, but he proved that he had perfected a technique to jump from great heights and survive. His use of alcohol braced him in the performance of these feats, and inebriation may explain what went wrong on his fatal jump. Certainly, he was warned in numerous newspaper articles. A year before his death one newspaper stated: “This is in bad taste, for although there is some tact and management in the feat, it is still unnecessarily sporting with human existence, and all such bravadoes should be discontinued.”

An explanation for Sam’s risk taking can perhaps be found in his motto, “Some things can be done as well as others.” He was a showman at heart and dressed for the occasion, in white pantaloons with a black sash tied around his waist. While at Niagara Falls, he walked about town with a pet bear on a leash; and in at least one instance he threw the poor animal from the platform into the river below, before he made his leap.

It is not surprising that Sam Patch is still remembered today, nearly two hundred years after his death. He was recognized in both literature and song. Notable American authors like Nathanial Hawthorne and Herman Melville referred to him, and Sam has several modern-day books written about him. There is even a packet boat named in his honor that gives tourists river boat rides on the Erie Canal in New York state, a fitting legacy for America’s first daredevil. Historian Paul Johnson calls Patch the United States’s first celebrity—an ordinary person who became famous for his feats.

Today the remains of Sam Patch lie buried in the Charlotte Cemetery in Rochester, New York. His gravestone has a bronze plaque on the back of it telling of his fatal encounter at the upper falls of the Genesee River on Friday, November 13, 1829. The gravestone is a modern one, having been placed there in the 1940s. His original grave marker was a wooden plank that simply said, “Sam Patch – Such is Fame.”

Sam Patch’s gravestone at Rochester, New York, which replaced the original one made of wood. Sam was probably born in 1799 and not 1807.

Notes

[1] Paul E. Johnson, Sam Patch the Famous Jumper (Hill and Wang, 2003), 19-26. [2] Ibid., 38. [3] Ibid., 39. [4] Ibid., 47. [5] “Reminiscences of ‘Sam’ Patch,” Providence Journal, August 6, 1916.