Rhode Island’s first lighthouse was constructed in 1749 on Beavertail Point, the southern tip of Conanicut Island (better known as Jamestown). Initially named Newport Light, Beavertail followed Massachusetts’s 1716 Boston Light on Little Brewster Island and Nantucket’s 1746 Brant Point Light. Thus, Beavertail Light has the distinction of being the third oldest lighthouse in what is now the United States and one of the first twelve selected by George Washington to be taken under federal government jurisdiction.

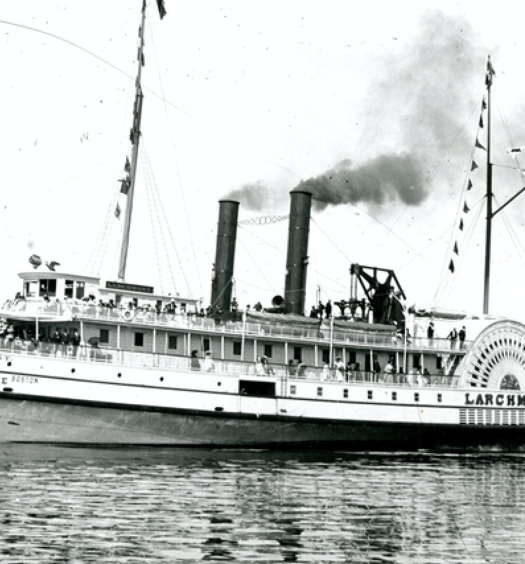

During the century following, eight additional Rhode Island lights were added. In the subsequent decades, maritime commerce, the lifeblood of Rhode Island—and the nation—multiplied and was over burdened by both sailing and steam powered vessels. Additional lighthouses were constructed to provide safe navigation for vessels entering the waters and harbors throughout the state. It was the era noted for transporting goods, passengers and materials over water. At the time, usable roads, motor transportation and railroads were in their infancy. Maritime trade tied isolated coastal towns and port cities together with the lighthouses showing them the way. Over 850 lighthouses including those in the Great Lakes were operational in the nation’s waters during that era.

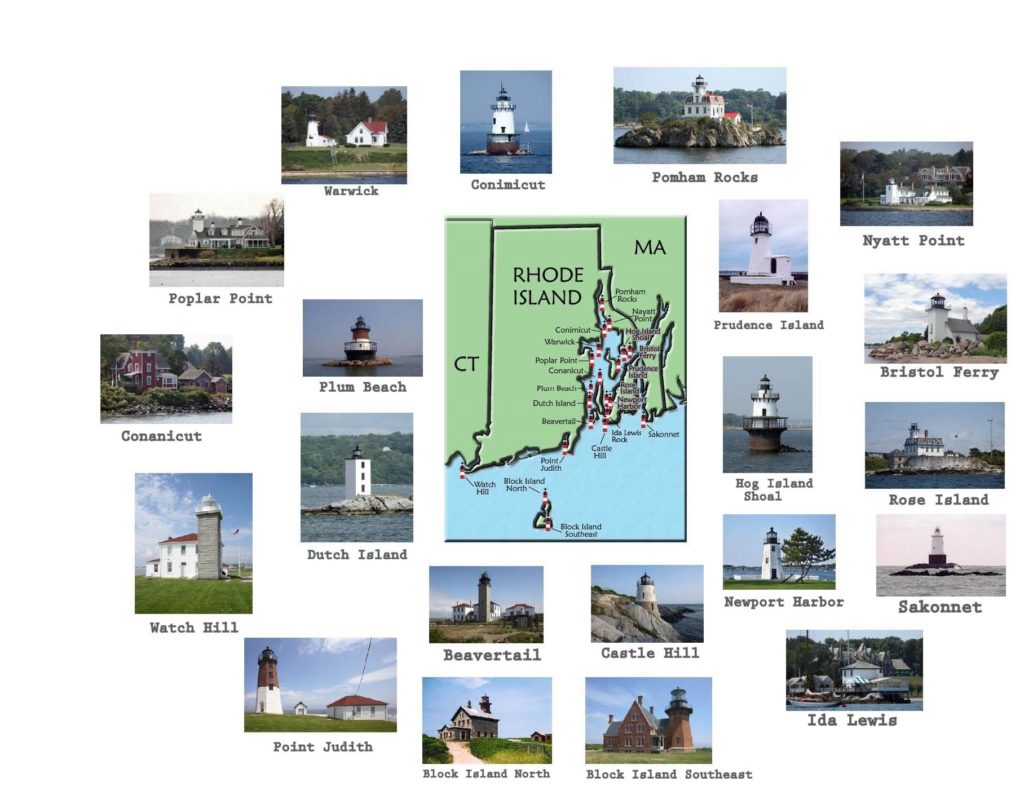

Three bodies of navigational waters—Rhode Island Sound, Block Island Sound, and Narraganset Bay—comprise over 400 miles of Rhode Island’s coast line. From 1749 through to 1901 thirty lighthouses were constructed along those shores. The last was Hog Island Shoal Light, which marked the entrance to Bristol Harbor and Mount Hope Bay. Only twenty-one lighthouse structures remain of which nineteen are listed in the National Register of Historic Places and fifteen are still considered active navigation aids.

Water transportation, primarily coastal vessels consisting of sloops, schooners and three-masted vessels, peaked in the late 1800’s as the Industrial Revolution boomed. Slowly, transportation of goods transitioned to shipping by faster and more economical trucking and railroad box cars. The change hurt lighthouses. New bridges were constructed, channels dredged and in some cases the lighthouse itself was removed. Some lights in Narraganset Bay, namely, Plum Beach, Nayatt Point, Bristol Ferry, Poplar Point and Sassafras Lights, succumbed to adjacent navigation improvements. Coastal shipping by sailing vessels began disappearing as water transportation moved to large motorized bulk carrying cargo vessels, tug boats, tankers, passenger ships and Navy vessels.

Along with navigation improvements, the U.S. Coast Guard, successor to the Lighthouse Service and its predecessor, the Lighthouse Board, began to deactivate unnecessary lights and found methods to reduce the number of its lighthouse keepers.

Automation, the act of operating the light and associated fog signal by electronic controls, began in 1960. The Coast Guard removed all its personnel from its lighthouses nationwide and in the process abandoned many of these structures to the elements. Once declared excess by the Coast Guard, they were disposed of by sale to the highest bidder by the General Services Administration. Warwick Light, Rhode Island’s last manned lighthouse, was automated in 1985. The inactive lights, no longer aids to navigation, were then to be disposed by sale, auction, or demolition.

Initially and intentionally, the U.S. Lighthouse Board, the agency under the U.S. Treasury Department, located lighthouses in geographic locations to best serve as safety beacons for vessel traffic. Unintentionally, they selected sites with exotic maritime venues that awed sightseers. The scenic waterfront sites, when coupled with the architectural attractiveness of lighthouse structures, came together, creating a romance with mystical beauty seizing imaginations of onlookers. Lighthouses symbolized America’s notable maritime past and captured the imagination though stunning photographs and picturesque vistas. Equipment such as the elegant jewel-like prism lenses fueled by whale oil lamps further enforced their historic pedigrees and reinforced the desire to preserve lighthouses for future generations to enjoy.

Nationwide, lighthouse enthusiasts and historians were alarmed at the federal government’s disposition policy and petitioned the U.S. Congress to recognize that lighthouses throughout coastal locations including the Great Lakes were historical icons that should be protected. The result was passage of the National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act of 2000 (the “Preservation Act”), under which each lighthouse that was declared excess by the U.S. Coast Guard, through the General Services Administration would first be offered at no cost to qualified municipalities and nonprofit organizations under a National Park Service preservation agreement.

Prior to the Preservation Act, of the thirty lighthouses constructed in Rhode Island, eight, have either been lost by storms (hurricanes) or purposely destroyed. In addition, thirteen existing lighthouses in Rhode Island were purchased before the enactment of the Preservation Act or obtained by private entities. Their waterfront values have since increased into the millions of dollars.

Because some of Rhode Island’s early lights were designed and constructed before the federal lighthouse agencies established specifications and rules, there is a wide range of architectural designs. Not until the 1850 did standardization take hold, and basic keeper residences and tower designs using granite or stone and cast iron became widely used.

Two examples are Watch Hill Light and Beavertail Light, both constructed in 1856, each of which used granite blocks from the same quarry in Westerly. The Watch Hill Light tower was built to a height of 45 feet, whereas Beavertail ended up at 54 feet. The keeper residences were identical until Beavertail warranted an assistant keeper, and a second keeper house was constructed in 1898 set perpendicular to the one adjacent to the tower.

During that same period the federal Lighthouse Board, concerned with more exposed lighthouse locations, moved from wooden structures to iron caisson lights that were sturdier and could be lowered to sink to the seabed floor, filled with rocks and/or concrete and supported further with rock foundations. These lights were named “sparkplugs” because of their appearance. Five were built in Rhode Island. Of those, Conimicut, Hog Island Shoal, Plum Beach, and Sakonnet lights remain active navigation aids. (The other, Whale Rock Light, was lost along with its Keeper in the 1938 hurricane.)

Three lights, Pomham Rocks, Sabin Point and Rose Island, were designed with comfortable cottages. Two of those have been saved and restored. (Sabin Point was purposely totally destroyed by fire to make way for a new Providence River channel in 1968.)

Conimicut Point Light was the first light in Rhode Island to be transferred under the Preservation Act to the City of Warwick. In August 2020, Watch Hill Light was declared excess property and ownership is expected to be transferred to the nonprofit Watch Hill Lighthouse Keepers Association. Hog Island Shoal Light at the entrance of Mount Hope Bay was eligible under the Preservation Act, but, when no qualifying organization requested the transfer of the light, in 2006 it was sold at auction to an out-of-state private party.

Beavertail Light Station, now a popular museum destination, is expected to become excess and transferred in 2021 to a partnership group to include the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (“RIDEM”), Town of Jamestown and the Beavertail Lighthouse Museum Association.

Both the Watch Hill Lighthouse Keepers Association and Beavertail Lighthouse Museum Association have submitted letters of interest and are awaiting application invitations from the National Park Service. It is expected that both lights and their fog signals will remain active navigation aids maintained by the Bristol U.S. Coast Guard Aids to Navigation Team (ANT) unit. The Watch Hill Light and Beavertail Light transfers were held up due to lack of funding needed to remove contaminated soil. Soil samples were finally taken and an extensive mitigation project of removing top soil was undertaken in January and February of 2020.

Government restrictions have not deterred the public’s appreciation of these historic structures and their need for preservation. Preservationists, historical organizations and philanthropic foundations, along with awareness of the general public, now play the roles of saving Rhode Island’s remaining lighthouses. Ten lighthouses are now under some level of restoration. The total cost to be expended is estimated at over $8,655,000. While these 19th century lighthouses now have stewards as champions, striving to save them their exposure to high winds, salt spray, and other severe environmental conditions means that the lighthouses require planned preservation procedures and annual maintenance.

Restoration and preservation is complicated and expensive because the tradesman-like skills and construction material used during the 19th century today are not readily available. The Rhode Island Historic Preservation and Heritage Commission, the state’s overseer of historic structures, is critical of modern-day methods. In response, contractors in many cases fabricate fittings and hardware replicated from corroded and disassembled unusable parts and assemblies in order to maintain original features.

Lighthouses surrounded by water add another dimension to the difficulties in restoration and maintenance needs. Often contractors, staff members and visitors must be transported to and from the site by boat. Weather and sea state dictate safe passage and thereby limit when services can be delivered. Excluding the two lighthouses on Block Island, which require ferry boats for access, Rhode Island has eight locations with structures considered remote or isolated. Two tour services, one from Quonset Point and the other from Jamestown and Newport, conduct a ten-lighthouse narrated cruise by ferry boat in lower Narragansett Bay, including a visit through Newport’s inner harbor.

Sakonnet Light with a cast iron caisson sits on a peninsula of rocks off Little Compton without any buffer from ocean waters. The other seven isolated lights are located within the confines of Narragansett Bay. They are considered “harbor lights” where exposure to heavy seas are not often experienced, yet can it can become hazardous to approach or land supplies in choppy waters.

Rhode Island Lighthouses and Current Status (February 2021)

[a] = name of lighthouse

[b] = when built

[c] = current owner (USCG is U.S. Coast Guard)

[d] = current status

[e] = comments

[a] Beavertail; [b] 1749-1856; [c] USCG; [d] Active; [e] Property to be transferred to new owner [a] Block Island Southeast; [b] 1875; [c] Private; [d] Active; [e] SE Lighthouse Foundation [a] Block Island North; [b] 1829-1868; [c] Private; [d] Active; [e] Town of New Shoreham [a] Bristol Ferry; [b] 1855; [c] Private; [d] Discontinued 1928; [e] Private residence [a] Bullocks Point; [b] 1872; [c] USCG; [d] Damaged 1938 Hurricane; [e] Demolished 1939 [a] Castle Hill; [b] 1890; [c] USCG; [d] Active; [e] USCG Search & Rescue Station [a] Conanicut; [b] 1886; [c] Private; [d] Inactive 1932; [e] Private residence [a] Conimicut; [b] 1868-1883; [c] Warwick; [d] Active; [e] City of Warwick 2004 [a] Gull Rocks; [b] 1887; [c] USCG; [d] Demolished 1961; [e] Too costly to repair [a] Dutch Island; [b] 1827-1857; [c] Private; [d] Active (private aid); [e] Privately maintained[a] Fuller Rock & Sassafras Point; [b] 1872-1923; [c] USCG [d] Fuller Rock Active; Sassafras Removed; No Dwellings [a] Gull Rocks; [b] 1887; [c] USCG; [d] Demolished 1961; [e] Too costly to repair [a] Gould Island; [b] 1889; [c] USCG; [d] Razed 1960; [e] Purposely burned down [a] Hog Island Shoal; [b] 1901; [c] Private; [d] Active; [e] Property privately maintained [a] Lime Rock; [b] 1854-1857; [c] Private; [d] Discontinued 1963; [e] Ida Lewis Yacht Club [a] Nayatt Point; [b] 1828; [c] Private; [d] Discontinued 1868; [e] Private residence [a] Newport Harbor; 1824; [b] USCG; [c] Active; [d] American Lighthouse Foundation [a] Musselbed Shoal; [b] 1873; [c] USCG; [d] Destroyed 1939; [e]1938 Hurricane [a] Plum Beach; [b] 1899; [c] Private; [d] Active (private aid); [e] Reactivated 2003 after 62 years [a] Point Judith; [b] 1809; [c] USCG; [d] Active; [e] USCG Sea & Rescue Station [a] Pomham Rocks; [b] 1871; [c] Private; [d] Active; [e] Friends of Pomham Rocks/Exxon [a] Poplar Point; [b] 1831; [c] Private; [d] Discontinued 1882; [e] Private residence [a] Prudence Island; [b] 1852; [c] USCG; [d] Active; [e] Privately maintained [a] Rose Island; [b] 1870; [c] Newport; [d] Active (private aid); [e] City of Newport 1985 [a] Sabin Point; [b] 1872; [c] USCG; [d] Destroyed 1968; [e] Interference with new channel [a] Sakonnet; [b] 1884; [c] Private; [d] Active; [e] Property privately maintained [a] Warwick; [b] 1827-1932; [c] USCG; [d] Active; [e] Used by USCG as residence [a] Watch Hill; [b] 1808-1856; [c] USCG; [d] Active; [e] Property to be transferred to new owner [a] Whale Rock; [b] 1882; [c] USCG; [d] Destroyed 1938; [e] Destroyed by 1938 Hurricane [a] Wickford Harbor; [b] 1882; [c] USCG; [d] Destroyed 1930; [e] Cost saving

A few nonprofit organizations and their benefactors were created specifically to save local lighthouses from further deterioration or demolition. Rhode Island’s lighthouses have enthusiastic volunteers and benefactors who recognize their historic value and need for preservation.

Of the twenty-one remaining lighthouses, sixteen are owned by the U.S. Coast Guard and operated as active navigation aids. Eleven of those (excluding the light and fog signal apparatus) are maintained by either a Rhode Island municipality or by a nonprofit, tax-exempt qualified Section 503(c)(3) organization.

Rhode Island Lighthouses Structures Maintained by Municipalities or Nonprofit Organizations

Beavertail Light (Beavertail Lighthouse Museum Association)

Block Island Southeast Light (Southeast Lighthouse Foundation)

Block Island North Light (Town of New Shoreham)

Conimicut Light (City of Warwick)

Dutch Island Light (Dutch Island Lighthouse Society)

Hog Island Shoal Light (Private out of state owner)

Plum Beach Light (Friends of Plum Beach Lighthouse)

Pomham Rocks Light (Friends of Pomham Rocks Lighthouse)

Rose Island Light (City of Newport)

Sakonnet Light (Friends of Sakonnet Lighthouse)

Watch Hill Light (Watch Hill Lighthouse Keepers)

With no funding forthcoming from the U.S. Coast Guard, which abandoned these sites, only cloistered donations from memberships and benefactors, plus competitive grants from private, state or federal agencies, have saved these historic sentinels. Philanthropic foundations, as well as state and federal agencies, have made meaningful contributions to preserve the state’s maritime history and architectural beauty.

No central Rhode Island organization exists combining or acting as spokesman or lobbyist for these lighthouse groups. Each nonprofit organization, staffed by volunteers, operate for the existence of its local lighthouse and strives to collect funds to undertake repairs, annual maintenance, and capital project preservation needs. With 25 percent of Rhode Island Lights destroyed and another seven unavailable to the public, the remaining fifteen lights are in continuous various stages of preservation.

The existing lights are old and require constant attention to limit corrosion, rot, sagging roofs, old floors, and general deterioration. They all need financial assistance. While local communities help, nonprofits are crucial for the future survival of the historic lighthouses. The purpose of these organizations is to save the structures for generations that follow and, in turn, to preserve their heritage, including to tell the stories of lighthouse keepers, their families, and a way of life of service to help others in peril.

The interiors of most Rhode Island lighthouses are not accessible to visitors partially due to geographical limitations and or limited organizational staffing. Conimicut, Pomham Rocks, Plum Beach, Dutch Island, Sakonnet Light, and the two lights on Block Island all require access by boat and some, while externally restored have empty or unfinished interiors. Dutch Island itself is off limits to visitors per RIDEM because of environmental issues.

Beavertail Light, adjacent to easily accessible Beavertail State Park, enjoys more visitors than all other Rhode Island lights combined. Its museum has been expanded to include all of its buildings and now includes modern interactive touch-screen displays that supplement the historic lighthouse artifacts on display. It also has a gift shop, as do the two lighthouses on Block Island.

Pomham Rocks Light completed its restoration, including its entire interior, and is now scheduling visitation days. Rose Island Light not only invites visitors, they accommodate overnight stays all year long. Only five lights periodically schedule public openings. These are at Beavertail, Block Island North, Block Island Southeast, Rose Island, and Watch Hill. All have historical displays and exhibits, and volunteer docents who provide additional information.

Point Judith Light was open for visitors prior to September 11, 2001, excepting the light tower. The property has since been closed to the public by the Homeland Security Department and fenced off for security reasons, since it also houses U.S. Coast Guard personnel and is still an active Search and Rescue Unit.

Websites

As awareness of preservation needs grow, nonprofit organization mangers and staff in addition to other media have embraced the use of online websites to promote information about their restoration projects and detailed history of their adopted lights. These include the following:

Beavertail Light Station: www.beavertaillight.org

Block Island North Light: www.lighthousefriends.com

Block Island Southeast Light: www.southeastlighthouse.org

Dutch Island Light: www.dutchislandlighthouse.org

Plum Beach Light: www.plumbeachlighthouse.org

Pomham Light: www.ponhamlighthouse.org

Rose Island Light: www.roseisland.org

Sakonnet Light: www.sakonnetlighthouse.org.

Watch Hill Light: www.watchhilllighthousekeepers.org

Additionally, both state and city information websites highlight lighthouses within their jurisdictions.

Other Websites Highlighting Rhode Island Lighthouses

http://www.unc.edu/~rowlett/lighthouse/ri.htm

http://lighthousefriends.com/ri.html

http://www.newenglandlighthouses.net/rhode-island.html/

http://www.rhodeislandlighthousehistory.info/lighthouse_part_1f.pdf (Richard Holmes)

[Banner image: Beavertail Lighthouse under restoration in 2006, the first major restoration in 150 years (Beavertail Lighthouse Museum Archives)]

Sources and Images

Jeremy D’Entremont, The Lighthouses of Rhode Island (Commmonwealth Editions, 2006)

Eric Jay Dolan, Brilliant Beacons (Liveright Publishing, 2016)

Richard Holmes, Rhode Island Lighthouses: A Pictorial History (You Lulu Inc, 2008)

Sarah D. Gleason, Kindly Light (Beacon Press, 1991)

Varoujan Karentz, Beavertail Light Station (Booksurge Publishing, 2008)

Rhode Island Division of Parks and Resources, website at http://riparks.com

U.S. Coast Guard Historians Office, website at https://www.nps.gov/maritime/inventories/lights/ri.htm

U.S. Coast Guard Light List, volume 1 (2016)

United States Lighthouse Society, Historic Lighthouse Preservation Handbook (Illusio Design, 1996)

U.S. Lighthouse Society, website at www.uslhs.org

Images: all from the Beavertail Lighthouse Museum Archives