[Editor’s note: The author of this article, Lynne Heinzmann, is the author of Frozen Voices, a wonderful new historical novel about the sinking of the SS Larchmont. She does a great job painting characters that you relate to want to know what will happen to them. At the end, she explains what part of her novel is historical and what part is invented by her based on reasonable historical suppositions. I very much recommend the book and hope Lynne writes more historical novels with Rhode Island as the backdrop.]

On the snowy afternoon of February 11, 1907, Jacob and Sadie Michaelson boarded the SS Larchmont in Providence, Rhode Island, for an overnight cruise to New York City. When the steamship’s purser noticed that they shared the same last name, he offered them a stateroom together on the ship’s Hurricane Deck. The couple laughed and explained that they were cousins, due to be married in a few weeks, and so would require two staterooms, for propriety’s sake. Their marriage never took place. Jacob and Sadie Michaelson and more than one hundred other people died in what was one of the worst maritime disasters in New England’s history.

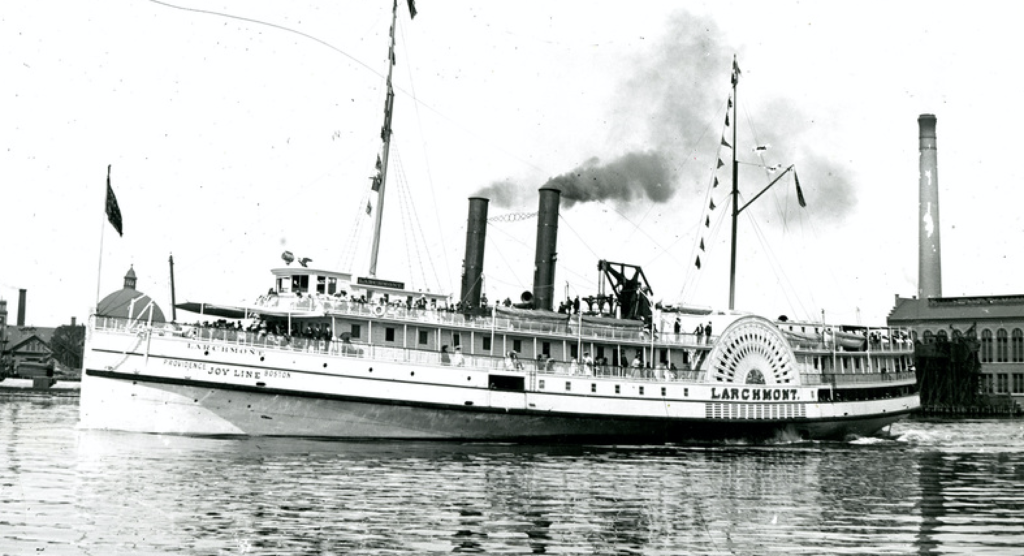

The SS Larchmont steaming out of harbor on a nice day. It has a sidewheel and two smoke stacks. Passengers are visible standing on all levels of the ship’s deck (Providence Public Library

The weather that night was bitterly cold with the temperature hovering around zero degrees. Although the skies were starry and clear, a fierce wind whipped the water into waves up to twenty feet high. Despite these brutal conditions, the Larchmont proceeded on its scheduled run to New York, leaving Providence only a half-hour late at around seven o’clock. The 23-year-old Larchmont was a wooden, side-wheel steamship, 252 feet long by 37 feet wide, painted white with two tall black smokestacks. At ten o’clock, as the ship exited the Narragansett Bay and turned west into the Block Island Sound, some lucky passenger retired for the evening to private cabins, for which they paid extra. Other less fortunate travelers adjourned to the ship’s saloon where they expected to sit up all night.

At around ten-thirty, Captain George McVay, a young man of only twenty-six, who was commanding his first vessel, checked conditions in the pilot house and then retired to his cabin, leaving John Anson, his first pilot, in charge of the ship. A few minutes later, the bow watchman called attention to the lights of an approaching sailing ship. Pilot Anson ordered the quartermaster to adjust the Larchmont’s course slightly so that the two vessels would not pass too closely in the churning waves. But the sailing ship seemed to change its course as well, heading straight toward the Larchmont. John Anson blasted four short warning whistles and ordered the ship turned hard to port, but it was too late. At ten forty-five on February 11, 1907, the Harry Knowlton, a heavily loaded three-masted coal schooner, plowed into the SS Larchmont, ripping a huge hole in the passenger ship and severing her main steam line thus rendering her without power.

The force of the collision and the ferocious seas caused the two ships to separate almost immediately. Frank T. Haley, the captain of the Harry Knowlton, seeing that his ship’s bow was badly damaged, signaled the Larchmont to come back to rescue them but the steamer quickly vanished from view, presumably continuing on its way. Captain Haley set course for the Rhode Island shore in an attempt to beach the ship. Quickly realizing that they were taking on too much water to make it to shore, he ordered his crew of six into a lifeboat. Although the Harry Knowlton ran aground and was pounded to splinters by the enormous waves, all seven crew members survived. Their lifeboat landed near the Quonochontaug Life-Saving Station where they spent three days recovering from frostbite and exposure.

The passengers and the crew of the Larchmont were not as fortunate. After the collision, the ship’s power went out almost immediately, leaving the passengers and crew drifting in utter darkness. The severed steam pipes released huge clouds of scalding steam throughout the lower decks, burning all who came in contact with it. Many passengers never made it out of their cabins. They were, perhaps, the lucky ones.

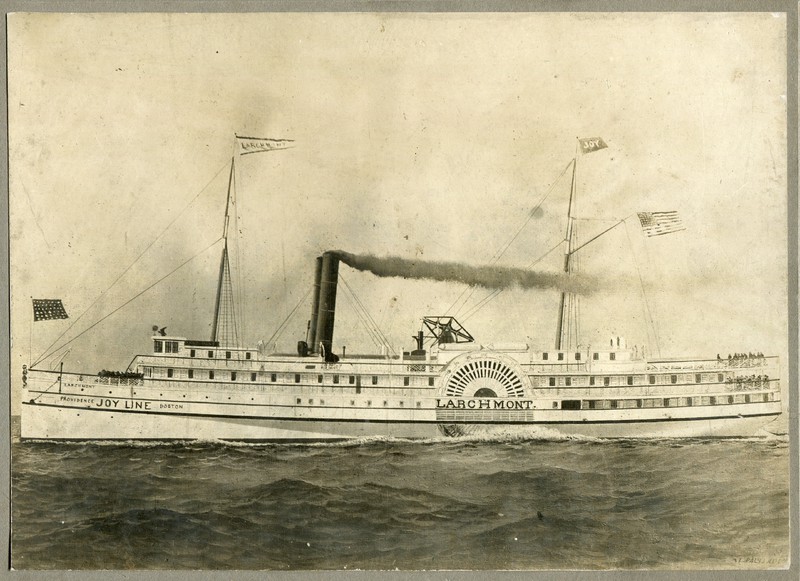

The SS Larchmont sank in collision with the Harry Knowlton on February 11, 1907 at about 11:30 p.m. off of Watch Hill and Block Island. In one estimate, 158 died and only 20 were saved (Providence Public Library)

For those few souls, many still in their nightclothes, who managed to grope their way through the dark, narrow passageways and find stairways leading to upper decks, pain and suffering awaited them. The temperature was near zero, the wind was blowing at up to sixty miles an hour, the frothy waves were constantly crashing over the ship drenching everyone and coating them with ice, and the Larchmont was sinking fast. Captain McVay ordered his men to quickly prepare the lifeboats. The crew and the few passengers on deck at that time boarded the boats and cast off from the ship. The captain, in a lifeboat with seven other crew members, ordered them to row around the sinking steamer in an attempt to rescue people from the water. They found no one and were soon blown away from the ship by the fierce winds. Within fifteen minutes of its collision with the Harry Knowlton, the steamer Larchmont sank beneath the mountainous waves.

Because the crew of the Harry Knowlton did not realize how badly damaged the Larchmont was, they did not immediately alert the authorities. The first anyone knew of the disaster was at around six o’clock the next morning when Fred Hiergesell, a sixteen year old passenger from the steamer, stumbled up to the North Lighthouse on Block Island, mumbling, “More coming, more coming ….” The islanders quickly mobilized their rescue personnel and dashed to the beaches. Soon the other lifeboats from the Larchmont washed up on shore, containing both living and dead victims of the collision. The survivors were all severely frostbitten and suffered from extreme exposure.

Once the Block Islanders realized the scope of the Larchmont disaster, they reasoned that some of the lifeboats from the vessel may have missed the island and might have been swept out to sea. Three island fishing boats, the Elsie, the Clara E., and the Theresa, sailed from the island in search of other survivors. About a mile east of Block Island, the crew from the Elsie spotted what appeared to be a raft with people clinging to it. Upon closer inspection, the craft proved to be a portion of the Larchmont’s Hurricane Deck with fifteen people aboard, eight alive and seven frozen to death. At considerable risk to themselves and their boat due to the dreadful cold and the extremely rough seas, the crew of the Elsie transferred the survivors to their vessel and then rushed them to the island for medical care. These were the last survivors of the Larchmont to be found.

All eight of the crew members of the Elsie suffered ill effects from their heroic endeavors that day, ranging from minor frostbite to chronic respiratory conditions. Edgar Littlefield was one of those crewmembers. Both of his hands were severely frostbitten during the rescue and his lungs were adversely affected, so much so that he had to spend an extended period of time in a sanatorium on the mainland. When he returned to Block Island, his continued ill health prevented him from going back to fishing and he was forced to take up a life of farming. However, despite these consequences, Edgar Littlefield and his crewmates repeated said throughout the rest of their lives that they did not regret risking their lives and health to rescue the passengers from the Larchmont and that, given the chance, they would do it again.

For their valiant efforts, the crew of the Elsie received Gold Medals from the Carnegie Hero Fund, which had been established specifically to reward civilians who performed incredible acts of heroism. The Hero Fund also distributed cash awards to the eight fishermen to provide college educations for all of their children, male and female.

After the Larchmont Disaster, the Steamboat-Inspection Service of the Department of Commerce and Labor conducted an inquiry into the accident to determine the cause and to assign blame. In the final paragraph of their report, the Service reported:

“We find, from the time that schooner Harry Knowlton and steamer Larchmont approached each other in such way as to involve risk of collision, that schooner Harry Knowlton was navigated in full compliance with the provisions of article 21, steering and Sailing Rules for Atlantic and Pacific Coast Inland Waters; that the movements of steamer Larchmont were in direct violation of articles 20 and 22 of the said steering and sailing rules, and we therefore attribute the loss of steamer Larchmont and schooner Harry Knowlton to careless and unskillful navigation on the part of the first pilot of the Larchmont, John L. Anson.”

This judgment was based primarily upon the fact that a sailing vessel automatically had right-of-way over a powered ship in public waters, so by virtue of it being a steamship, the Larchmont was responsible for getting out of the way of the Harry Knowlton. Therefore, when the two ships collided, the fault was attributed to the person in charge of the Larchmont at the time, First Pilot John Anson.

During their interviews with the Steamboat-Inspection Service, the crew of the Harry Knowlton testified that they had maintained a steady course throughout the incident. This testimony was in direct conflict with that given by the surviving Larchmont officers, who stated that the other boat had altered course at least twice, and that it was, in fact, these alterations that caused the collision. Although the truth will probably never be fully determined, several months after the accident, a rumor concerning the disaster circulated among members of the New England shipping community. According to this rumor, at the time of the accident, no one was at the helm of the Knowlton. In an attempt to escape the bitter cold and ferocious winds, the crew had lashed the ship’s wheel and had all gone below deck to keep warm, allowing the ship to go wherever the strong wind pushed it. This theory will certainly never be verified, but it would explain the ship’s erratic change of direction noted by the Larchmont’s officers.

The sinking of the Larchmont is often described as the “Titanic of New England.” Of the approximately one-hundred-fifty-six passengers and crew members aboard that night—the exact number is unknown since the passenger list went down with the ship—only nineteen survived, and two of those succumbed to pneumonia within a week. Seventy-four ice-encrusted bodies washed up on the beaches of Block Island and were shipped home for burial. The remainder either went down with the ship or drifted out to sea in lifeboats, never to be seen again.

[Banner image: The SS Larchmont steaming out of harbor on a nice day. It has a sidewheel and two smoke stacks. Passengers are visible standing on all levels of the ship’s deck (Providence Public Library)]

This article is written by Lynne Heinzmann, author of Frozen Voices, a historical novel about the sinking of the SS Larchmont, which is available from Amazon.com. To find out more information about Lynne and Frozen Voices, please visit her website: www.LynneHeinzmann.com.