A book review: The City State of Boston: The Rise and Fall of an Atlantic Power, 1630-1865. By Mark Peterson. Princeton University Press, 2019.

Once upon a time there was an English settlement with disappointing prospects in its natural resources. Without the lucrative cash crops of other New World colonies, its merchants resorted to shipping, including a triangular trade with the West Indies with African slaves. The colony jealously protected its autonomy and resisted the British crown’s attempt to reassert control. It led other colonies in seeking full independence from Britain, and only reluctantly agreed to join the federal union.

If you think that colony is Rhode Island, you would be right. But according to Mark Peterson, a professor of history at Yale University, it could also be Massachusetts. Across 740 pages, he retells that state’s early history on its own terms:

My inclination has been to call this story a tragedy. The city-state of Boston would be the noble hero of the drama, whose virtuous aspirations toward self-governing autonomy and an internal ethic of charity were eventually undermined by fatal flaws.

Its chief flaw, says Peterson, was its economic dependence on slave-based societies, which eventually induced it to cede sovereignty to the federal union.

The City-State of Boston is thus a remarkable, if awkward achievement. Engagingly written, it treats the state as an entity in its own right, not the inevitable sub-unit of a more interesting whole. This is a book that’s fun to read and think about, even if you disagree with the arguments.

As for Massachusetts’ apparent similarities with Rhode Island, the book helped me clarify those differences better than anything else I’ve read. Unfortunately the book actually says almost nothing about Rhode Island, so we have to do that work ourselves.

We can dispense with the book’s main argument. It suggests that “Boston,” which includes the entire Massachusetts Bay colony and often other Puritan colonies, had the economic makings and political ambitions of an independent metropolis, and somehow could have steered a course away from slave-based commerce. But it’s hard to imagine any struggling, entrepreneurial society resisting the lure of trading with the only commercially successfully economies in the New World. Rhode Islanders made the same awful bargain, arguably with more energy and creativity. Yet they resisted the federal union far more aggressively than their northern neighbor – something Peterson never examines.

Indeed, Massachusetts hardly seems to have been reluctant about the union, even if the vote was a bit close. It joined within three months of the Constitution’s signing, the sixth of thirteen states to do so. By contrast, Rhode Island was the last to join and held off for two years, until the federals prepared to impose tariffs and the merchants of Providence and Newport threatened to secede from the state. Throughout its history, Massachusetts’ citizens willingly saw themselves as part of larger wholes, either the British empire, the “Protestant International,” or the United States generally (as “the Athens of America”).

It’s true that Massachusetts’ representatives to Congress complained about the domination of the southern colonies, the Embargo Act of 1807, and “Mr. Madison’s” War of 1812. They were so upset that they led the way in organizing the Hartford Convention of 1815, which Rhode Island also supported. Yet the convention stopped short of threatening to secede, and the war’s end defused all talk of secession. Then it turned out that Massachusetts, like Rhode Island, benefitted enormously from joining the union, as it led the country in industrializing and found ready buyers for its cheap cloth. National markets in finance and industry enabled Bostonians to maintain their wealth even as textile profits fell. Massachusetts has done just fine: ever since the mid-19th century, it has been among the richest states per capita (passing Rhode Island in the early 20th century).

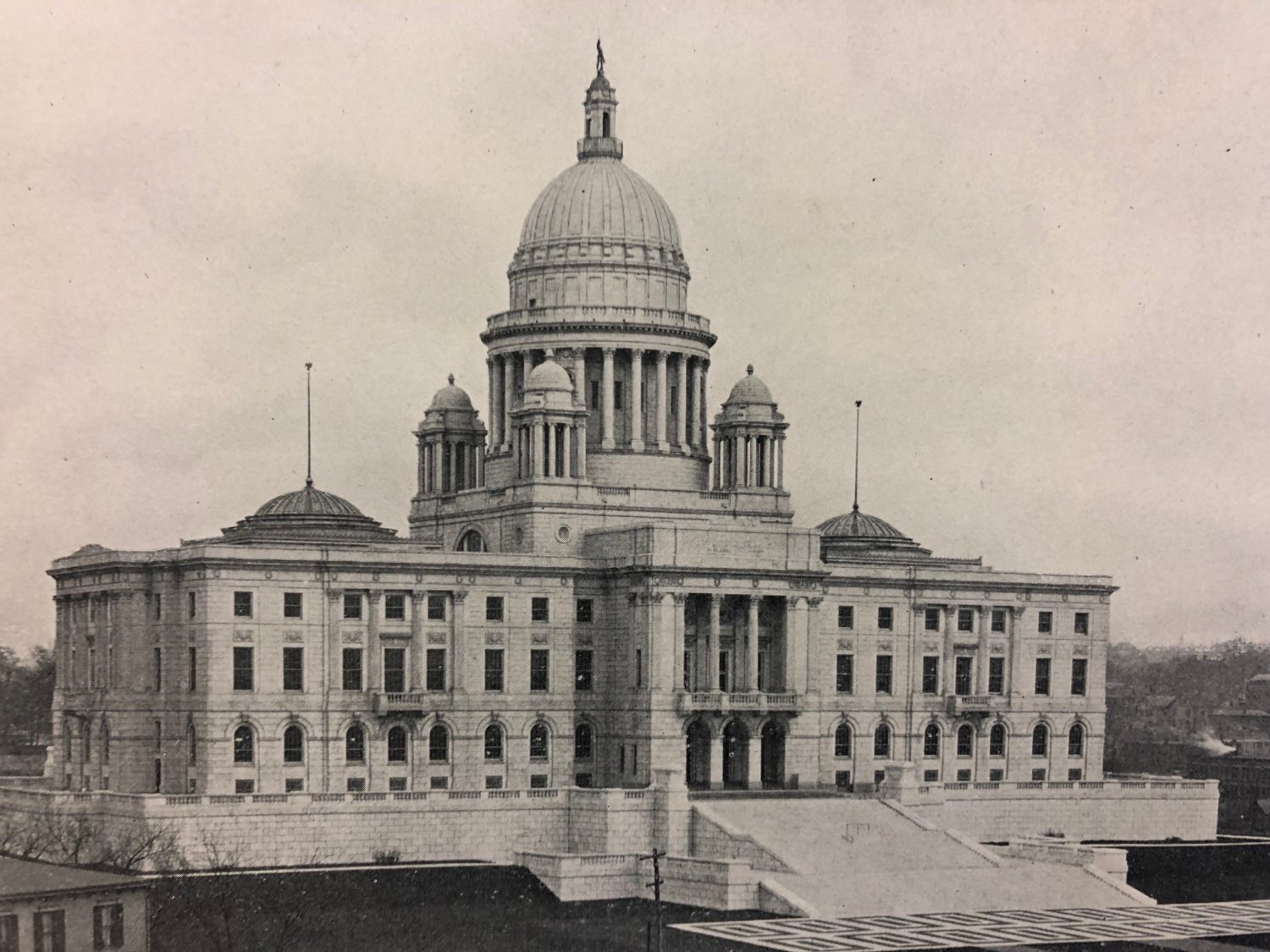

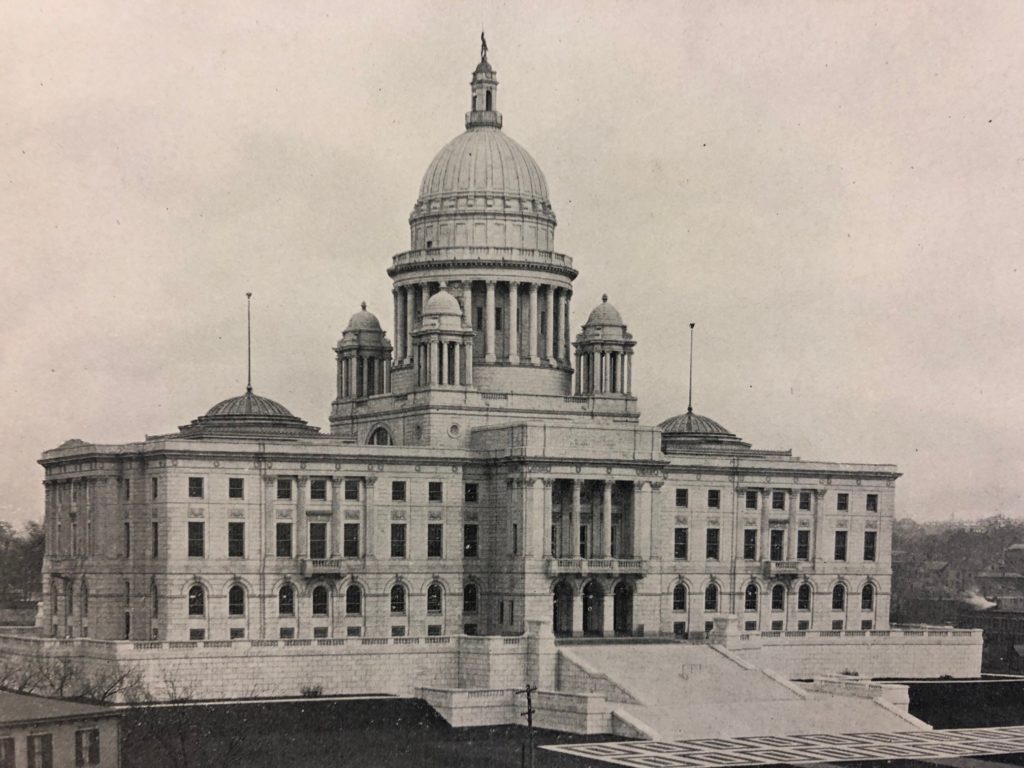

Rhode Island State Capitol Building, circa 1905, a reflection of the state’s prosperity at that time (Board of Trade Magazine)

The problem wasn’t union itself, but that Bostonians weren’t in charge. Peterson nicely describes how Massachusetts historians after the Civil War gave the newly emerging American history books a strongly Boston bent – as though New England represented the purest forms of Americanism. If the region couldn’t dominate the political agenda, at least it could lead the way culturally.

By the end of the book, it’s clear that the author is far more interested in Massachusetts’ imperial ambitions than its desire for autonomy. Bostonians wanted to lord it over other people, gradually extending their economic and political dominance over the New England hinterland. They mistakenly saw the federal union as a way to have their cake and eat it: to boost their commercial prospects without losing their autonomy.

That’s not surprising, because the Puritans who initially dominated Massachusetts excelled at disciplined, collective effort. They were proud of their accomplishments and believed in evangelizing to others. That collective spirit is why the region’s financial industry centered on Boston, not in Rhode Island which began establishing banks around the same time. And Boston continues to have impressive strengths in money management and mutual funds, with Rhode Islanders enjoying some of the spillover.

Unfortunately the book says very little about Massachusetts’ multiple attempts to absorb “Rogues’ Island,” which Cotton Mather called “the cesspool of New England.” That’s probably because those attempts all failed miserably – but more detail here would have been another interesting test of Peterson’s argument.

Indeed Rhode Islanders, far from lording over others, mainly wanted to be left alone. Not only were they the first to rebel from Britain and the last to join the union, but they had little interest in grand projects or in imposing their ideas on others. As Roger Williams ruefully discovered, it was hard to get much collectively done at all, because Rhode Islanders were self-selected to be independent and non-conformist. Government at all levels was weaker than elsewhere.

Aside from persecuted minorities such as Jews and Quakers, hardly anyone came to America specifically to settle in Rhode Island. Most of the early population were disaffected New Englanders seeking “soul liberty” or at least greater economic freedom. Vermont, after all, had more people until the 1880s. It’s no surprise that Rhode Island led the country in entrepreneurship (paper money, industrialization), but failed to keep up when success depended on amassing large amounts of capital. Collectivist Boston, the book describes, also invested in public services for livability as well as generous (for the time) social welfare.

Textiles are another example of the contrast. As Samuel Slater and other innovators developed their mills, they kept the factories relatively small and specialized. Unlike the Boston Associates’ massive integrated complexes at Lowell and Lawrence, Rhode Islanders preferred to stay flexible, and not to trust fellow capitalists. Their approach was apparently just as profitable as their northern neighbors, because textile manufacturing lacked major economies of scale.

Boston’s approach, however, enabled Massachusetts to develop much more of a corporate economy with financing and other advanced services. Massachusetts’ collectivist spirit also made it easier for bankers to support the budding electronics industry when the state was looking for something to replace the fading textile sector in the 1950s. Irascible Rhode Island may excel at basic innovation and entrepreneurship, but Massachusetts can scale up better.

Setting aside these contrasts, what’s most interesting about the book is its focus on Bostonians as a people in their own right, not as Americans in one corner of the country. That focus gives the narrative much more drama and power than conventional state histories. The book reminded me a bit of Rockwell Stensrud’s fine Newport: A Lively Experiment, 1639-1969. That city was the closest counterpart to Boston until the Revolution, a shock that undermined much of the city’s pride and autonomy, along with its economic base. Stensrud doesn’t go so far as to make Newport a dramatic character, but his focus on the city works well as a narrative. We need something equivalent for Providence.

“Plant of the National India Rubber Company, Bristol, R.I., Operated by United States Rubber Company, Samuel P. Colt, President, circa 1892 (Board of Trade magazine)

For most of the colonial period, Bostonians did see Massachusetts, and perhaps all of Puritan New England, as their “country,” separate from other British settlements and from the Crown. But that changed in the late 19th century, whereas Rhode Islanders continued to distrust the rest of the union. To take a notorious example: when the textile industry began to decline in the 1920s, most of the New England states cooperated to find solutions to the crisis. Rhode Islanders, however, refused to join in, until the Great Depression made a go-it-alone strategy untenable.

Peterson concludes by calling for renewed emphasis on the interests of individual states and regions:

In the twenty-first century, it has become less certain that the nation-state should be the normative form of governance, and that the ideals of responsible self-government can be achieved in units reaching the hundreds of millions.

Local loyalties have arguably increased in recent years, as seen in trends as diverse as the decline in people moving across state lines, and the revival of community investments in specific places. The Covid pandemic made people more conscious of their states as well. The federal government may be able to command more tax money, but with political polarization nationally, state and local governments are increasingly where the action is. Local history is also getting renewed interest, as readers of this site can attest.

Massachusetts has a saliency on the national level that Rhode Island will never have, so we can’t expect an outside historian to write the equivalent book about the Ocean State. But The City-State of Boston can serve as a model for history that gives a colony and state an identity separate from the rest of the country. Ironically, despite its tiny size, that separate identity may make more sense for “insular” Rhode Island than for many other states.