Benjamin Quarles once wrote that the loyalty of black Americans during the American Revolution “was not to a place nor to a people, but to a principle, freedom.”[1] In late 1779 Newport’s black residents, free or enslaved, faced a predicament: should they stay or should they go? Should they choose freedom but risk an uncertain future under British protection, or should they stay enslaved in wartime Rhode Island? In Newport, prior to the war, nearly twelve percent of the residents were black, and almost a third of white families owned at least one slave.[2] The tiny colony of Rhode Island, in addition to playing a major role in the American slave trade had the highest proportion of enslaved people in New England, some 6.3 per cent of the population.

Newport had been occupied by British and Hessian troops for almost three years, and while many white Patriots had escaped to the mainland, some of the blacks they left behind had worked for the British. The British army was finally leaving the city in October 1779, taking several dozen leading white Loyalists (and their slaves) with them and seemed willing to take self-liberated slaves belonging to Patriots with them. The blacks had perhaps heard about Dunmore’s Edict of 1775 which freed Virginia slaves willing to fight for the British; it is more likely they had heard about the Phillipsburg Proclamation of June 30, 1779, which freed any slave in Patriot hands, man, woman or child, military service not required.

It is not known how many Rhode Island blacks liberated themselves and left the colony, but it is estimated that 20,000 blacks left their enslavers in the new United States during or after the Revolutionary War. Many simply melted away, moved to another area, changed their names, or moved out of the country; due to lack of documentation, most can never be traced. There is, however, a source of information about for about 3,000 of those who left the United States. It is the Book of Negroes, a three-volume handwritten ledger compiled in 1783. The British Army commander ordered it compiled in case the Americans wanted to claim compensation for their “property” and both British and American inspectors checked the people getting on the ships.[3] It gives names, age, former owner (some were still enslaved in which case their current owner), place of residence, the date they left and a brief description. They were “tall and stout” or a “feeble wench” or a “fine child,” some had tribal scars, a few had missing limbs. Fifty Rhode Island names, which included four babies born automatically free in New York, appear in it, though there were almost certainly more as the inspectors or their clerks were not always punctilious in noting places of origin, and it was not necessarily in the would-be evacuee’s interest to tell the truth. The majority of the Rhode Islanders were taken to Nova Scotia in the Canadian Maritimes, five went to Germany, and two to Abaco in the Bahamas.

The cover page to the Book of Negroes, which is actually a set of two ledgers that lists the names, ages, and descriptive information of about 3,000 enslaved African Americans, indentured servants, and freedmen who were evacuated from the United States along with British soldiers at the conclusion of the American Revolution (National Archives)

The British were not philanthropic abolitionists; they offered freedom to all slaves in Patriot hands (though not those belonging to Loyalists) as part of their effort undermine the American “rebel” armies. The 1783 Treaty of Paris, whose negotiators, both British and American included slave traders, contained a clause recognizing slavery, whereby the British agreed not to “carry away any Negroes or other Property of the American inhabitants.”[4] The British commander-in-chief in New York Sir Guy Carleton declared, however, that a promise was a promise and told George Washington to break it would be a “dishonest Violation of the public faith.” He insisted that any person of color who could prove they had been under British protection before the provisional treaty was signed in late 1782 was free.[5] Although Washington was somewhat resigned to his own losses, a British observer said the America commander-in-chief had urged the return of the slaves to their former owners “with all the Grossness and Ferocity of a Captain of Banditti.”[6]

To preserve the blacks from slave catchers who were already hovering in the city, the British treated them as Loyalist refugees (indeed, some had served in Loyalist regiments, though the majority had not), and from April to November 1783 loaded 3,000 of them onto transports along with an estimated 30,000 white Loyalists.[7] The majority went to the Canadian Maritimes where they were promised land and supported by handouts for the next three years. While the white Loyalists received land allocations relatively quickly, many blacks were still waiting in 1791, when the question of should we go or should we stay arose again.

The answer for almost 1,200 of the Nova Scotian blacks was go, to try another place in the hope it would be better. They were responding to an offer from the Sierra Leone Company, a group of British abolitionists and Evangelical businessmen. They wished to create an alternate economy in West Africa by growing cash crops instead of trading human cargo, while meanwhile converting the local Africans to Christianity. At least one Rhode Island family was among those who went to Sierra Leone in 1791. Once there, the Nova Scotians demanded a say in their government and using the revolutionary rhetoric they had learned in America argued for their rights as free men and women, causing the leading British abolitionist, William Wilberforce, to complain that they were “as thorough Jacobins as if they had been trained and educated in Paris.”[8]

The profile of the Rhode Islanders was different from the average traveler listed in the Book of Negroes. Of those listed, two thirds were from Virginia (1,128), South Carolina (474) or New York (448), and while fourteen percent of the total claimed to have been born free, over half of the Rhode Island passengers, including fourteen women, three men and eleven children, convinced the inspectors they were either born free or had been freed by their masters. The Rhode Islanders were old and young, ranging from fifty-three years to five months. Four were of mixed race. Forty of them were from Newport. One had worked as a drummer boy in a Hessian regiment (he and his family went to Germany where he probably served in the Margrave’s private army). Several of the men had worked as carters and laborers in the Wagon Master General’s department in New York, while women worked as laundresses and cooks for the army.

This excerpt from the Book of Negroes, in the third column, gives the names of African Americans seeking to sail to Canada and other places, along with other identifying information (National Archives)

Their enslavers ran the gamut, too. There was a turncoat British spy who had been Speaker of the Rhode Island General Assembly, a Jewish merchant, a few Episcopalian worthies, some determined Patriots, a Loyalist who took his slaves into exile, but died the following year, and a whole group of fence-sitters, waiting to see which way the war would go.

We know the Rhode Islanders’ names, and many traveled in family groups. Jeremy and Keatie Dyer, Bridget Wanton and her daughter, Jemima Bull and her three children, Bridget Wanton and her daughter, Caesar Nichols and his mother and her friend, Arthur Bowler and his wife and daughter, Rhose Groseman, her husband and daughter, Fonlove Jackson and her children, and Hana Hazard and her children. There were also single men such as Peter Parker, Jacob Wanton, Pompey Lindon, Amos Carrey, Cato Rogers, Jack Rogers, Cuff Potter, John Potter, Samuel Warner, and a few single women, including Patience Jackson, Diana Carder, Jenny Toney, Lucy Johnson and Nancy Mumford.

Poor eighteenth-century people are hard to trace. Most of the black Loyalists would have been at best semi-literate, and they rarely owned property, but the British who were supplying them with rations in Nova Scotia for several years kept good records. The brief descriptions in the Book of Negroes and results of extensive archival research illuminate the variety of the refugee experience.

What follows is an examination of the experiences of a well-documented handful of these risk takers illustrating the complexity of slavery and its aftermath, showing examples of creative survival, family formation and re-formation, the growth of religious autonomy and political activism.

Peter Parker, a “stout fellow” with one arm who had been freed, he said, by Thomas Parker of Providence, found a steady job with Thomas Mallard, formerly a British army officer, in St. John, New Brunswick. Mallard erected a large two-story building and while the first floor was an inn, the large room upstairs was used successively as a meeting place for the provincial legislature, a theatre, and a Masonic Lodge. There was plenty of work for his four free servants, but Mallard also owned Jenny, a “likely, healthy negro wench, of about 17 years of age” who he offered for sale in 1787 “for want of employ.” When he found no buyer, he shipped her to Barbados where she sold for £56. Selling recalcitrant slaves to the Indies was an ever-present threat and this must have been unnerving for Peter Parker and the other free black servants.[9]

“Ordinary man” Jacob Wanton, formerly enslaved by rum distiller Latham Thurston in Newport, changed his name and his occupation when he got to Nova Scotia. He became Jacob Wanton Nicholson and started making hats. He was the only one of the Rhode Island self-liberated who said he freed himself on hearing of General Clinton’s declaration at Phillipsburg, though he did not completely escape servitude as he indentured himself to ship’s pilot, James Cotton, in order to travel.[10]

“Stout mulatto wench” Keatie Dyer was aged twenty-five when she left New York, and told the inspectors she was a servant, not a slave. Jeremy Dyer has not been traced. Although the two Dyers were owned by the same man, they were not, it seems, related. Thirty years later she twice petitioned the New Brunswick courts to assert her claims to land she had farmed and improved since she arrived in the province. As in many similar cases, her title was dubious as her occupation of the land was a result of the dislocation of the previous owners, French-speaking Acadians, who had earlier displaced the Mi’kmaq, the indigenous inhabitants of the area. She told the court she had arrived with the troops in 1783 and was now an “Old Woman between 60 and 70 years of age.” She had traveled to Nova Scotia (the northern part of which became New Brunswick in 1784) as a servant to a junior officer in the King’s American Dragoons, a Loyalist unit founded by the multi-talented physicist and inventor Colonel Benjamin Thomson, later Count Rumford. Her son now lived on the land, she said, and farmed it with his five children, and she wanted to establish their right to it.[11]

Fifty-three-year-old Cuff Potter went to Nova Scotia “on his own bottom” as a former employee of the British army and not beholden to any master. Perhaps unusually for someone who is described as a mulatto, he had an African name; Cuffee denoted a boy born on a Friday. His mother, who bore him about 1730, must have had memories of Africa. By 1783 he was described as an “ordinary fellow” not stout, not fine, not worn out, despite his age. He told the inspectors he was formerly a slave of Ralph Potter of Newport. There were a lot of Potters in Rhode Island, but no sign of a Ralph in Newport. Perhaps the inspector misheard. The examinations must have been cursory for the inspectors to list sixty-eight men, twenty-seven women and fifty-one children in the Book of Negroes in one day. It is very possible Ralph may have been farmer Rowse Potter, captured by the British along with his slave Cuff in North Kingstown on August 24, 1778 and taken to Newport. Rowse Potter was released three weeks later and put on a ship back home, but there was no mention of what happened to his slave, who may have stayed in Newport until he was evacuated with the troops more than a year later.[12] Over the next four years he served the Crown, hence the phrase “on his own bottom.” He was old to be a soldier; he may have been a carter. Once he arrived in St. John his name disappears. He could have changed it; he could have moved on; he could have died.

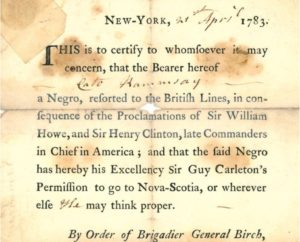

This is one of the few surviving Birch Certificates of Freedom, given to those listed in the Book of Negroes who qualified to leave New York City on British vessels for Nova Scotia in 1783 (Wikipedia)

Fifty-two-year old Jenny Toney, who appeared “worn out” to the inspectors in 1783, got a new lease of life. She had been freed by bill of sale by Daniel Underwood of Connecticut and Rhode Island several years earlier and by 1774 was head of a household of three black people in Newport. She was among the minority of the Rhode Islanders receiving land in Nova Scotia and managed to reunite with at least one daughter who had been sold to an owner in Massachusetts. She was one of the fortunate blacks who received an allocation of land and she was farming her twenty acres in the late 1780s.

“Stout wench” Nancy Mumford, twenty-one, was born free after her father, Bristol, purchased her mother from a Mrs. Mumford, and she had the papers to prove it. She formed a new family with James Prior, a freeborn Jamaican cooper she met in New York. Like many of the Rhode Islanders they lived in Birchtown, on the southern tip of Nova Scotia. With its 1,500 inhabitants it was for a while the largest black town in the Western hemisphere. Birchtown collapsed in the early 1790s, its fall exacerbated by almost five hundred of the residents choosing to go to Sierra Leone, so Nancy and her husband moved north-east to the Nova Scotian port of Annapolis where they thrived. The Priors belonged to the Anglican church, and parish records from St. Luke’s, Annapolis, include marriages for two young Prior women, both identified as black: Phoebe in 1820, and Margaret in 1824. And most significant of all, a black woman named Nancy Prior was buried there on September 27, 1827. Nancy Mumford Prior would have been about sixty-five years old, living long enough to see her granddaughters married.[13]

“Ordinary fellow” Ben Frankham, freeborn in Johnston, Rhode Island, misled the inspectors by telling them he was born free in Charleston. Although had recently been in South Carolina with British troops he did not wish the authorities to know he was a deserter from the Continental Army. He had a long, well-documented career in Nova Scotia, and could have been one of those advised to stay in Canada rather than move to Sierra Leone as by 1781 he was married with small children and well-established in the local community.[14]

Patience Jackson, a “very likely wench”, freeborn of mixed race—the inspectors noted her as “mulatto”—became Patience Warrington and her descendants can be traced in Nova Scotia for several generations.

The all-female Quack family may have been Rhode Islanders—the inspectors grew lax when they had a large number of travelers to process and did not always note place of origin. Fifty-year-old “ordinary” Elizabeth, twenty-eight year-old “stout” Jean and seventeen-year-old “likely” Sally all said they were freeborn, and the next year when the Black Loyalists were mustered for the purpose of allocating rations, they had two younger daughters with them, Katy and Polly. Quaco is a West African name for a boy born on a Wednesday, and there were several Quacos in Rhode Island, some of whom supported the American side in the war. Jehu and James Quaco served in the First Rhode Island Regiment of the Continental Army and Fortune Quaco worked for the Continental Navy as a marine on the 36-gun frigate Confederacy. Quaco Honeyman, a freed man of Newport, on the other hand, is credited as being the first African American spy for the British.[15]

Arthur Bowler, a “stout fellow” of thirty-four, brought from Africa as a boy and enslaved by Metcalf Bowler of Newport, wealthy merchant, colonial official and British spy, stayed in Rhode Island longer than any of his fellows, finally leaving in 1781. He traveled from New York to Nova Scotia with his born wife and twelve-year-old daughter, both freeborn in Portsmouth, Rhode Island. They were taken initially to Port Mattoun, which almost immediately failed, and then to Birchtown where he was eventually awarded forty acres of land. He had not yet seen it, let alone started clearing it, when he decided to go Sierra Leone where he lived long enough to see his grandchildren go to school. He was probably a Baptist, (his second wife was the widow of a Baptist elder) and thus a member of a more moderate faction in Sierra Leone. The Methodists were considerably less accommodating. In Newport he had worshiped in the “Negro Section” of the Anglican Trinity Church. In Rhode Island he was acquainted with leading members of the black community such as the entrepreneurial diarist Cesar Lyndon (who elected to stay, while one of his fellow slaves, Pompey Lindon, opted to go). Soon after Bowler arrived in Sierra Leone he frightened a leopard away from the hut where his wife and daughter were sleeping.[16] He outlived his erstwhile master by at least twelve years; by comparison, Metcalf Bowler died in poverty, though with his reputation intact, as his spying remained undiscovered until the 1920s.[17] Arthur Bowler lived with a modest competence and his freedom.

Rose Gozeman, a “stout wench” of twenty-four, formerly the property of Newport farmer Jonathan Easton, traveled to Canada with her husband, formerly from Connecticut, and freeborn daughter Fanny. In the late 1780s they suffered along with most of the other residents of Birchtown; a blight had affected crops, the weather was bad, British food handouts had ended, and food was in short supply. Black leader Boston King wrote in his memoir “Many of the poor people were compelled to sell their best gowns, even their blankets, several of them fell down dead in the street thro’ hunger…poverty and distress prevailed on every side.”[18] It was during these starving times that Rose’s husband, who was scraping a living as a woodcutter, went to the magistrates and confessed he had killed an ox. He told them he meant to salt it up and it would feed his wife and family for the winter, but he panicked, “he had not the courage to flay or skin him” so left the carcass, and when he returned four days later he found it starting to rot. He nevertheless took some of the meat which he ate “while it was fit in any way to eat” and threw away the rest. And then his “conscience some him” and he turned himself in.[19] There is no record of his punishment, but he and his family moved across the Bay of Fundy to New Brunswick where his later children were born. One of them, John Thomas Gosman is the ancestor of a well-known Canadian operatic singer Measha Brueggergosman; recent DNA testing of her brother suggests one of her ancestors came from what is now Cameroon in West Africa.[20]

Five of the Rhode Islanders went to Germany, or more exactly, to Hesse. Two of the five were a ship’s cook and his daughter—what happened to them after their journey is unknown. The fate of the others is a little clearer, despite the fact that many potential sources were lost when the Allies bombed Kassel during World War II. Local Hessian aristocrats had long used black children, usually boys, as Kammen-Mohren, chamber Moors, and during the Revolutionary War least 150 black Americans were formally enlisted in Hessian regiments, some as soldiers, others as laborers. Many adolescent boys, too young to bear arms, were trained as musicians, playing fifes and drums and thereby freeing soldiers to be musketeers or grenadiers. One such was Cesar Nichols, a “fine boy” twelve years old. He sailed to Canada with his mother Rhose, an “ordinary wench” of thirty-six, both of them enslaved to Benjamin Nichols of Newport and Warwick, and their friend Cathern Townshend, a “likely wench” of seventeen who said she was indentured rather than enslaved. All three of them probably worked at the White Horse Tavern in Newport which was run by Walter Nichols, cousin to Benjamin, and his wife, and housed Hessian officers during the British occupation of Newport. The landgrave of Hesse-Kassel Frederick II (uncle of George III of Great Britain) already had black drummers in his local regiment, and decreed that “No negroes are to be dismissed, but they shall all be retained, and until they can be transferred to my First Battalion Garde they shall receive a monthly bonus payment from the accumulated peace budget from my royal chatoul.” It is therefore very likely that Cesar found himself in the elaborate uniform of Frederick’s private army.[21]

The most unusual destination for a Rhode Island slave was the tiny island of Abaco in the Bahamas. Twenty-two-year-old Bridget Wanton, a “stout little woman” and her five-year-old daughter were among the eighty blacks who were taken there. She had belonged to the Loyalist Colonel Joseph Wanton Jr., a member of the second wealthiest family in Newport, slave ship owner, Harvard graduate, and twice deputy governor of the colony, who took her with him to New York when the British evacuated Newport. He died unexpectedly the following year, and she said he left her free. Unlike Wanton’s widow, who the General Assembly felt sorry for and granted the rents from some of his confiscated properties, Bridget had to fend for herself. She met Captain John Davis, who was organizing the Abaco Loyalists, and went to the island in the summer of 1783. The settlers soon discovered the first site to be a poor choice as most of the buildings were flattened in a hurricane, and though the climate was otherwise good, the soil was too sandy, fresh water was scarce. Though they discovered that sea island cotton would grow, within two years it was infested with chenille bugs, and a little later, when Eli Whitney developed his cotton gin, the demand for sea island cotton fell.[22]

Ben Freebody met the inspectors who listed him in the Book of Negroes as a thirty-five-year old “ordinary fellow” but he decided at the last minute not to go to the Maritimes, but to stay in New York. This was a mistake and added to a long list of his misfortunes. In 1774 he was one of three slaves belonging to Newport merchant and distiller Samuel Freebody. Like many other slave owners Freebody rented out “surplus” labor, by the day, week or month, and hired Ben to a ship’s captain in 1775. Ben was whipped and badly mistreated and forced to work on a privateer for several years. He never saw a share of the prizes, and neither did his owner, which became the subject of legal friction after the war. As Ben stayed in New York he had to find lodgings and a job. Within months he contracted smallpox, which he blamed on carrying his master’s clothes to the washerwoman. He went blind in one eye and lost his job, and his landlord was threatening to sell him into slavery to realize his back rent. In desperation Ben wrote to Freebody “I’m sensible Dear master I belong to you” and returned to his owner and slavery in Newport. He remained a slave for the next sixteen years, but he was far from happy. In August 1790 Freebody signed a pass, which said he allowed “my Servant, Ben, to absent himself from my Service Thirty (30) Days, in order to Look out in the Country for a person to buy him, as he is discontented living with me. I wish him a better Master. I will sell him for a Reasonable pay and Price.” Ben would have been in his early fifties by then, blind in one eye, probably still bearing the scars of Captain Brattle’s whippings. Freebody must have been very unkind or very hard up to expect to get any money for him, however “Reasonable” the price.[21]

The stories of these self-liberated slaves leave a complicated legacy. Abandoning Rhode Island was a gamble that did not always succeed. But neither, as in the case of Ben Freebody, did staying always work out. The early years for many of the black Loyalists were difficult, as they are for most refugees. It is arguable that those Rhode Islanders we can trace in the archives who left on British ships were almost always better off in the short and medium term than the ones they left behind, though what happened to those whose names disappear remains a mystery. Rhode Island passed a gradual emancipation law in 1784, and by the beginning of the nineteenth century there were very few enslaved people in the state; however, their lives and working conditions were far from ideal. Some of the refugees in Nova Scotia found themselves working as sharecroppers to people with more land; those who went to Sierra Leone had the vote (even women, for a while) though they also faced war and disease. From the late 1790s there was a conscious effort to provide training for the Nova Scotians as pharmacists, teachers, clerks, and minor officials and after the British abolition of the slave trade in 1807 many Nova Scotians found themselves employers of “recaptured” Africans, rescued from slave ships by the Royal Navy. Those who went to the Bahamas risked re-enslavement after the waves of Florida Loyalists arrived with their own slaves. Some of those who went to Germany may have fared well as “exotic Moors” in the Landgrave’s army as long as they were young and handsome.

But at least they were all legally free.

[Banner image: A recreation of a settler’s hut at Birchtown in Nova Scotia, Canada (Jane Lancaster)]

Footnotes

[1] Benjamin Quarles, The Negro in the American Revolution (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1961), vii. An article that also covers Rhode Island enslaved persons who ran away to Newport is Christian M. McBurney, “Freedom for African-Americans in British-occupied Newport, 1776-1779, and the ‘Book of Negroes,’” Newport History 87 Summer/Fall 2017, no. 276, 1-40. I completed most of my research on my article before this article was published. In addition, my article is intended to go further, following some of escapees to Canada and beyond. [2] According to the 1774 census, there were 1590 families in Newport, comprising 7,917 white people, 46 Indians and 1246 blacks, to a total of 9,208 people. John Russell Bartlett, arranger, Census of the Inhabitants of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, 1774 (Providence, 1858). [3] A transcription of the American version of the Book of Negroes, which is slightly different from the British one, is in Graham Russell Hodges ed., The Black Loyalist Directory: African Americans in Exile After the American Revolution (New York: Garland, 1996), and it is also online at htto://www.blackloyalist.info/sources. [4] While Benjamin Franklin was the head of the American delegation, his colleagues included South Carolina planter and slave trader Henry Laurens, while Richard Oswald, Britain’s chief negotiator, was a former slave trading partner of Laurens, and formerly the principal owner of Bunce (Bance, or Bence) Castle in the Sierra Leone river, where captured Africans were penned awaiting the horrors of the Middle Passage to the New World. [5 William Smith, Historical Memoirs of William Smith, 1778-1783, W.H. W. Sabine, ed., (New York: New York Times and Arno Press, 1971), 574, quoted in Maya Jasanoff, Liberty’s Exiles: American Loyalists in the Revolutionary World (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2011), 89. [6] Quoted without attribution in Alan Gilbert, Black Patriots and Loyalists: Fighting for Emancipation in the War for Independence (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012), chapter 7, fn. 58. Simon Schama, Rough Crossings: Britain, the Slaves and the American Revolution (New York: Harper Collins, 2006), 144-149, has a lively description of this meeting. [7] Cassandra Pybus, “Jefferson’s Faulty Math: The Question of Slave Defections in the American Revolution,” William and Mary Quarterly 62, 3rd series (April 2005). [8] William Wilberforce to Henry Dundas, April 1,1800, Melville papers Add MSS 41085, British Library, quoted in Cassandra Pybus, Epic Journeys of Freedom: Runaway Slaves of the American Revolution and Their Global Quest for Liberty (Boston: Beacon Press, 2006), xi. [9] See Harvey Amani Whitfield, North to Bondage: Loyalist Slavery in the Maritimes (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2016), 52 [10] See Elaine Forman Crane, A Dependent People: Newport, Rhode Island in the Revolutionary Era (New York: Fordham University Press, 1992), 25-29. [11] Petition of Catherine Dyer, 15 May, 1821, Fredericton, “Black Loyalists in New Brunswick, 1783-1854, Atlantic Canada Virtual Archives, diplomatic rendition, document n. Dyer-Catherine_1815_01. RS 108: Index to Land Petitions: Original Series, 1783-1918, Provincial Archives of New Brunswick, Fredericton, New Brunswick. [12] Robert Pigot to General Sullivan September 14, 1778, quoted in Christian M. McBurney, “Freedom for African-Americans in British-occupied Newport, 1776-1779, and the ‘Book of Negroes,’” Newport History 87 Summer/Fall 2017, no. 276, 39, fn. 53. [13] See website “African Nova Scotians in the Age of Slavery and Abolition,” St. Luke’s parish records at https://novascotia.ca/archives/africanns/archives.asp?ID=66&Page=200402132&Language. [14] Shirley L. Green. “Freeborn Men of Color: The Franck Brothers in Revolutionary North America, 1755-1820.” Doctoral Dissertation, Bowling Green State University, 2011. [15] Christian M. McBurney, Spies in Revolutionary Rhode Island (Charleston SC: History Press, 2014), 74-75. [16] Lt. John Clarkson Diary, (19 March 1792 – 4 August 1792) University of Illinois, Chicago. Special Collections, Sierra Leone Collection, Box 1, Folder 4. My thanks to Suzanne Schwartz for this reference. [17] Jane Clark, “Metcalf Bowler as a British Spy,” Rhode Island Historical Society Collections 22 (1930), 101-17. See also McBurney, Spies in Revolutionary Rhode Island, 55-61. [18] “Autobiographical memoir of Boston King, a fugitive slave from South Carolina who became a teacher and minister in Sierra Leone,” serialized in 1798 in The Methodist Magazine. See online article at http://blackloyalist.com/cdc/documents/diaries/king-memoirs.htm [19] Court records in Nova Scotia Archives, RG60 vol. 42.6 (1789) and RG 60 Vol. 46.4 (1790). [20] See online article at http://www.cbc.ca/whodoyouthinkyouare/2012/09/measha-brueggeralready.sman.html. [21] See Maria I. Diedrich, “From American Slaves to Hessian Subjects: Silenced Black Narratives of the American Revolution,” in Mischa Hone, Martin Klimke, Annette Kuhlman, eds., Germany and the Black Diaspora: Points of Contact 1250-1914 (New York: Berghahn Books, 2013), 93-108. A chatoul refers to monies available at the discretion of the monarch. [22] Jasanoff, Liberty’s Exiles, 231. [23] Letter addressed “Ever honour’d Master,” from Benjamin, slave to Samuel Freebody, April 8, 1784. One of three letters, a bill, three depositions and two pages of litigation notes concerning the case of Ben Freebody, which was heard in several Rhode Island courts in 1786. Rhode Island Historical Society, Mss. 9003, Vol. 16, 97-103. The information on his contracting smallpox was from Samuel Freebody’s unsigned and undated litigation notes in the Rhode Island Historical Society collection. My thanks to Joanne Melish for showing me this material.