“Unh, Biology 2?” the secretary replied, “That’ll be in Edwards Auditorium.” It was the Fall of 1969, and I was the newest faculty member in the old Department of Zoology. At the time, the University of Rhode Island (URI) was not a very cosmopolitan place. I was the first faculty member in the department to have received his/her Ph.D. from an institution west of the Hudson River!

Many folks, especially the staff, appeared to speak a foreign language, which I later learned was called “Swamp Yankee”:

“Ya wants ta find someplace ta git brake shoos fa’ ya’ Fahd? Pitcha’s Garage mebbe has some.” Unh, yes, of course, just as you say.

I was also the youngest new faculty member by a long shot. I had gotten my Ph.D. from the University of California at Davis at age 27, then spent two years doing post-doctoral research at the University of Washington in Seattle. Boeing had just started making 747s, and the city was rolling with money. And world-class restaurants—almost as good as in the city of my birth, San Francisco. On the other hand, my first experiences with Rhode Island restaurants of the time gave me roughly the same experience as if someone inserted a 15,000-volt cable in my mouth, then said “Enjoy!” as he turned it on. How times have changed.

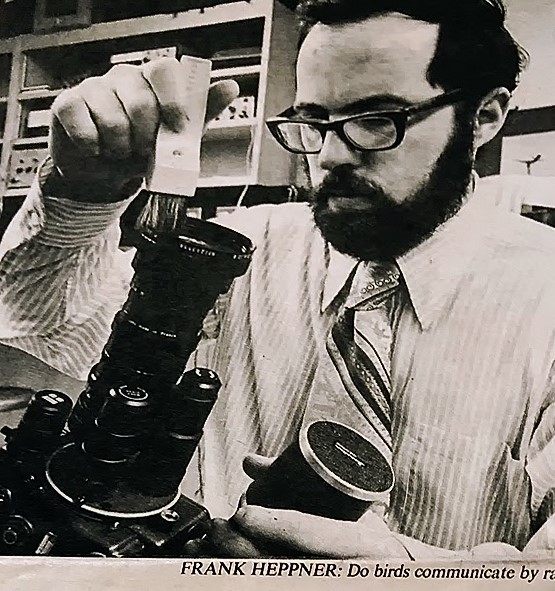

Professor Frank Heppner in the 1970s. A professor of biology, he specialized in ornithology at the University of Rhode Island (Frank Heppner Collection)

I took the job at URI as a quirk of fate. I had WANTED to stay on the West Coast after my post-doc, but as it turned out there were no suitable faculty openings on the Pacific coast at the time I was looking. The URI job popped up in March, and in desperation, I took it. My only experience with the East Coast had been a dreadful freshman year at Rensselaer Polytechnic in Troy, New York, in 1958. After that experience, I had vowed that if I ever had a choice between Hell and the East Coast, I’d jump at Hell in a heartbeat.

The job at URI involved doing research in a field of my interest, teaching some assigned courses, and if I proved to be not totally incompetent at that, some courses of my choice. There was a third component to the job, “service,” which I later found out meant helping to run the place, by spending time in administrative jobs. My first semester there I taught Biology 2 (by myself), which had 920 students, shared an upper division course, and offered a graduate seminar-in addition to getting my bird research started.

Wait a minute, 920 students! When “920 students” sank in a couple of days after my arrival, I asked the departmental secretary where it was taught—it was Edwards Auditorium. I found out where Edwards was, and decided to take a look at it before classes began. Ominously, it didn’t look much like an “auditorium” as I approached it. I went through the front door, and Holy Walnuts! It wasn’t an auditorium. It was a THEATER! Stage curtain. Theater organ. Green room. Dressing rooms. Projection room. Balcony. Ticket office. And they wanted me to give LECTURES there?

After my heart slowed down to maybe 200 beats/minute, I started to walk around. Well, maybe this wouldn’t be so bad after all. In my last semester at Washington, they gave me an opportunity to team-teach a large intro bio class with a wonderful tough-guy faculty member named Ken Osterud. Ken looked like a gangster, but he also showed me 47 different ways for students to cheat on exams which I never would have thought of. Ken was also a photographer and liked to show his relevant pictures to class to the accompaniment of taped music, an idea I stole with great enthusiasm.

I walked around the auditorium, and slowly came to the realization that if I played it right, Bio 2 might not be so awful. I was a photographer myself, and I knew that without strong lighting on a face, in a portrait the facial features tend to disappear. And if you couldn’t see a lecturer’s face, how did you know that the lecturer thought something was really important?

Voila! A glance around the room provided an answer. Because it was a theater, there were spotlights all over the place. There was a podium on the stage that the spotlights could be aimed at. If you chewed the class out because of their lousy performance on the last exam, they could see every furrow on your angry forehead.

The first day of classes, I wore my best suit. (The suit was custom tailored—I had a good starting salary. Relatively speaking, Assistant Professors made a LOT more money then than now.) Following Osterud’s precedent, I played classical music before class. At the STROKE of 9:00 am to the last crash of cymbals, I walked onstage, and my introduction was almost exactly the same then as it was 40 years later. “Good morning, ladies and gentlemen. I am Professor Frank Heppner, and I will be your instructor for Biology 2. Bio 2 will be very demanding of your time, thought, and energy, but you will learn things here that will be useful for the rest of your lives . . . .”

As time went on, I discovered other practical things. Because it also served as a movie theater, there was a huge screen behind the stage. At about this time, the concept of “multi-media” started to kick in in higher education. At that time, it meant using two slide projectors side by side. One image showed the general idea, the other showed the details. Hmmm. If two projectors are good, nine would be much better. So, some of my lectures evolved into slide shows with hundreds of pictures.

I had done photography of school stage shows when I was in high school, and I knew that under strong light, an actor had to use stage makeup if he/she wanted the audience to see your facial features. So, I went up to the theater department, and Professor Joy Spanabel showed me how to use stage makeup. I would arrive at Edwards twenty minutes before lecture, go to the dressing room, put on my makeup, and it’s SHOWTIME! The closest student was twenty feet away when I was on stage, so after lecture, I disappeared backstage, and took three minutes to peel off the makeup. I told the students some cock-and-bull story that I had to phone my lab right after every lecture, so I couldn’t see them until a couple of minutes after lecture. I then met with the mob of students who had questions. I don’t think any of them ever discovered my secret.

Eventually my colleagues discovered these antics, and to my surprise, I never drew any grief from the Chair, or my fellow instructors. I think the Cornell and Princeton pipe-puffers just thought, “Oh, he’s from Berkeley. I hear they’re all like that.” Fortunately, by the end of my first year, I got my research off the ground, and never drew any flak about my teaching eccentricities.

I still keep a little bit in touch with URI, and from what I can see, the present-day school is about as much like URI in 1969 as is the University of Mars. The ratio of full-time to part-time faculty, the ascendence of the social science fields in university governance, and the importance of grant-getting would make today’s URI almost unrecognizable to a time-traveling young faculty member from 1969. Does that mean that URI isn’t as good today as it was then? Not at all—it’s just different.

The Decline of Eccentricity

When I finished my scientific training in the late ‘60s, a reasonably bright young scientist could go either into industry/government or academia, much as he or she can today. However, industry was perceived as a hive for personality deficient corporate drones, the “Man in the Grey Flannel Suit” of IBM legend, or Riesman’s “Lonely Crowd.” If you were a child of the ‘60s, you wanted to do your own thing and a university was just the place to do it.

As a Berkeley graduate of 1962, the choice for me was clear. However, before I took the faculty job at URI in 1969, I did not realize how insular the school was at the time. As mentioned, I was the first faculty member in the Zoology Department to have received his Ph.D. from a graduate institution west of the Hudson River. And I had been an undergraduate at Moscow West, as Berkeley was known in certain quarters.

However, once I settled in, I discovered that this “differentness” was precisely the reason that I had been hired so easily. The young bucks in the rapidly expanding and ambitious URI Zoology department had decided that they wanted to compete on a larger playing field than New England state universities historically had, and they actually thought they were going to be able to mop up the floor with Brown University, which they perceived as old, fusty, and stodgy. So, fresh blood. Ah, the sweet naivety of youth.

Having discovered that URI’s perception of Berkeleyites was that we were oversexed, drug fiend radicals, I had a certain reputation to live up to, and I didn’t want to disappoint. As I hadn’t done a hiring seminar, I gave some thought to the first department seminar I would give once I was established. I decided not to talk about my post-doc work, fascinating as it was, but a new field that I thought was tremendously exciting, especially as Neil Armstrong had stepped on the moon only a few months before. So, I decided to give a review paper on exobiology, or the investigation of the possibility of extraterrestrial life, which was very trendy, and was becoming a “respectable” scientific field, with the advent of Project Ozma in 1960, and NASA’s establishment of the SETI program in 1972. I had been a rabid amateur rocketeer as a teenager (something wildly improbable today, due to safety concerns), so this came naturally to me.

The usual point of these department seminars was to bring in outside experts. Well, if I was going to talk about alien life, why not give the seminar as an alien life form? With the cooperation of the department chair, I kept out of sight until seminar time, and walked in as a full-dress alien. One of the most senior members of the department (Yale and ex-Navy) sitting in the front row bit his pipe stem in half. It was a wild success.

I followed this with similar eccentricities in my teaching. My maxim was that if you don’t have their attention, you can’t teach them, and I was shameless about getting their attention.

At the opening lecture of my giant general bio class, I wore a three-piece suit, conservative tie, shiny shoes, and a pocket watch with chain. The second lecture followed suit. I played classical music over the PA that ended exactly when the class was supposed to start, 9:00:00 a.m.

Two sessions after the first lecture, I drove a motorcycle into the class’s auditorium, dressed as an outlaw biker, with “Born to be Wild” instead of classical music playing on the PA. Why? The topic of the lecture was, “What’s the difference between something that’s alive, versus something that is not alive?” The vast majority of the students had looked at this question in high school biology, where they were given a list to memorize of characteristics that distinguished between alive or not, like respiration, excretion, etc. The biker, whose stage name was Jack Savage, explained to the class that he LOVED his bike. But how could you love a “thing?” He pointed out that you COULD love something that wasn’t human, like a dog. But a motorcycle? He then explained his insight. Before he was invited to be a high school dropout, he took a biology class, and had to memorize a list of characteristics of living things, as had most of the students. Living things require energy. Living things respond to stimuli, etc. . . . Then it hit him. His bike had the characteristics of living things; therefore, the bike was alive, thus he could love it!

He then went down the list. Living things respire. He pointed out the bike’s air cleaner. Living things require energy. He pointed to the gas cap. He came up with six or seven characteristics of living things, then asked for the class’s help. Maybe he forgets some. Hands went up all over the auditorium. One by one, he showed that the bike had the characteristic that the student came up with. Then came the clincher. The bike couldn’t reproduce.

That stumped him. By no stretch of the imagination could he imagine where the bike would reproduce itself. If he parked his Harley next to a petite Yamaha in the garage, and came back six months later, there wouldn’t be a bunch of little Mo-Peds scooting around the floor. But then he said that observation made him very sad. By now, class participation was widespread.

Remember, this was 900 students in a classroom with a balcony. Class participation in this type of setting was almost unheard of. A student invariably asked, “Why does that make you sad?” The “biker” (a.k.a., me) replied, “Because I’m gonna have to go down to the convent and tell sister Maria Theresa that she ain’t alive, because she ain’t never gonna reproduce!” Pandemonium. Then he asks the class, “So that’s it? If you don’t have the natural capacity to reproduce, you’re not alive?” Silence. They know there has to be something wrong, but nobody knows what.

The biker then pulls a roll of cash out of his pocket, holds it up and says, “I will give this $10,000.00 to anybody who can produce for me the son or daughter of a mule. All mules are born sterile.” Pandemonium again. There then followed a more-or-less straight lecture that introduced the questions of when to pronounce someone legally dead, and the question of defining death in an AI robot. A high proportion of this class planned on going into medicine one way or another, so it was a legitimate question to pose for them.

I also gave a Halloween lecture on the “Biological Basis of Myth and Legend” dressed as Count Dracula, who was carried into the lecture hall in a coffin borne by six teaching assistants. There then followed an absolutely straight historico-medical lecture about werewolves, vampires, the Loch Ness monster, etc. A later lecture on Evolution was given by Thomas Huxley, speaking for Charles Darwin.

However, as my career as a large class lecturer drew to a close, I began to notice a subtle shift in the students. Instead of viewing these “character” presentations as a welcome break from demanding and technical routine lectures, and responding with laughter, applause, and participation, the students would become nervous. Class participation plummeted. This wasn’t on the syllabus, many students complained. How could you take notes? What would be on the exam? Where was the PowerPoint? Sadly, I realized that the times, they had a changed. Post-retirement life was becoming more attractive.

And for faculty, there was a complete turnaround in the acceptance of eccentricity in academia versus industry. Now, if you want to be weird, you work for a software company. University full-time science faculty appear to be currently viewed by university administration as single-purpose, grant-getting machines, and any activity that departs from the driven pursuit of overhead money is frowned upon.

For faculty, forty years ago was, to quote Charles Dickens, “The best of times.”