This article is being published on the 250th anniversary of the seizure of the Gaspee.

“In a certain sense, the War for Independence began at sea when patriots clashed with the British on Narragansett Bay some two years before the momentous engagements at Lexington and Concord. In what can be considered the first armed confrontation of the American Revolution, veteran mariner and privateersman Abraham Whipple [1] led fellow Rhode Islanders in the seizure and destruction of the British schooner Gaspee after the vessel had run aground while pursuing suspected smugglers. This organized attack emboldened the first open, armed opposition to British authority in America.” From the Foreword to the book Commodore Abraham Whipple of the Continental Navy, by Sheldon S. Cohen.[2]

Compared to other states, especially Massachusetts and Virginia, Rhode Island has never properly celebrated its significant history.[3] As Rhode Island historian Samuel Arnold noted as early as the 19th century, “While each sister state has had her historian to give enduring form to the records of her daring deeds, to make known to men her claims to high distinction, and to contribute each his part to the grand fabric of our national history, Rhode Island alone has stood aloof, remained inactive, or failed at least to assert her indisputable place among the earliest in Council and the foremost in action. No wonder that rival states have claimed the precedence in many bold designs wherein they acted well but simply followed where Rhode Island led.”[4]

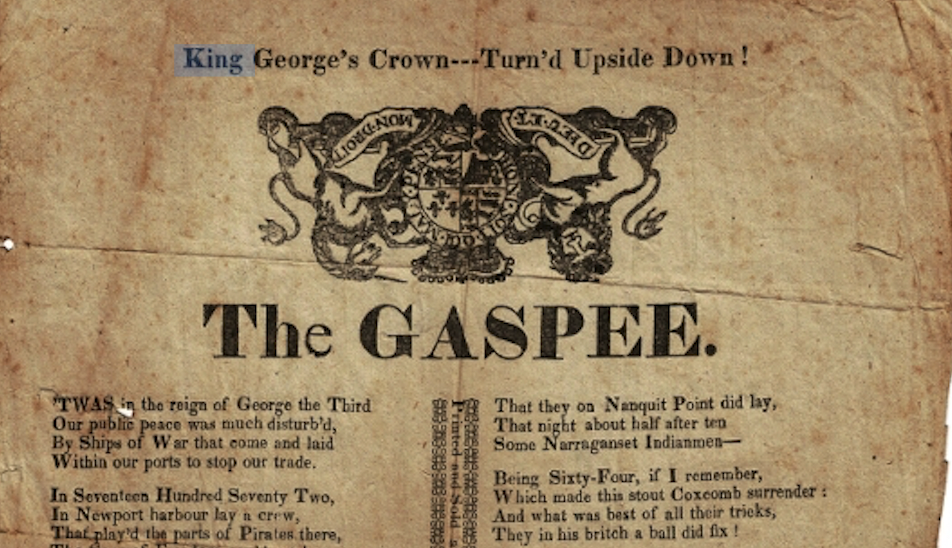

One of the great incidents leading up to the American Revolution was the burning of HMS Gaspee in Narragansett Bay. In modern times this event each June is celebrated in the village of Pawtuxet with a Gaspee Day Parade. It is a wonderful local tradition. But the incident gets little national attention. As historian William R. Leslie noted in his essay, The Gaspee Affair: A Study of Its Constitutional Significance, “The burning to the water line of his majesty’s schooner Gaspee while she was lying hard aground on a sandspit [Namquit Point] in Rhode Island’s Providence River [Narragansett Bay] has long been recognized as a singularly important event. Although it occurred on the night of June 9-10, 1772, nearly three years before Lexington and Concord, it was nevertheless of major significance in leading to the outbreak of war between the American colonies and the Mother Country. Indeed, perhaps the musket ball which wounded Lieutenant William Dudingston, commander of the Gaspee, was really an earlier shot heard ‘round the world.’”[5]

The story of the affair had ramifications here in America but also in England. The incident was also one of the main reasons the colonies formed standing committees of correspondence. According to a prominent contemporary historian, Mercy Warren Otis of Massachusetts: “Perhaps no single step contributed so much to cement the union of the colonies and the final acquisition of independence as the establishment of committees of correspondence.”

The following highlights the event:

- – On the night of June 9 – 10, 1772, about eighty intrepid patriots boarded eight long boats and rowed from Fenner’s Wharf in Providence to His Majesty’s schooner Gaspee, then aground off Namquit Point in Warwick.

- – Earlier the Gaspee had run aground on a sand bar while pursuing the packet Hannah. The packet’s captain, Benjamin Lindsey, was intentionally baiting the schooner and with superior knowledge of the waters of Narragansett Bay led the schooner into shallow waters where the British revenue vessel grounded.

- – The Gaspee and her commander had been much reviled by coastal traders for too rigorously enforcing the revenue laws and by colonials for raids on land. Rhode Island merchants and seamen had complained of abuses committed by Lieutenant Dudingston, but they fell on deaf ears at the Royal Navy. A warrant for Duddingston’s arrest and a trial would do no good, as Dudingston stayed on his vessel and so a warrant could not be served. Rhode Islanders felt they then had to take matters into their own hands, outside of legal strictures.

- – When Captain Lindsey brought word of the Gaspee’s plight, a group of men lead by merchant John Brown and one of his sea captains, Abraham Whipple, met at Thomas Sabin’s Tavern on the Providence waterfront and plotted the destruction of the Gaspee. Aroused by a boy’s beating of an alarm drum, patriots streamed to the waterfront and soon the plotters had sufficient officers and seamen to execute their plan.

- – Arriving at the Gaspee in eight boats the raiders, accompanied by another boat from Bristol, quickly boarded the ship and in the ensuing scuffle the Gaspee’s commander, Lieutenant William Dudingston, was shot and severely wounded in the groin.

- – After stripping the schooner of its valuables and removing all of the nineteen British officers and sailors, the ship was burned. When the flames reached the Gaspee’s gunpowder stores the vessel exploded. (To this day it is not certain whether the Gaspee was intentionally set afire. Since all of the British officers and sailors were removed before the fire started, that strongly suggests the fire was intentional.)

- – News of the Gaspee’s destruction spread quickly throughout the American colonies and accounts of the event were carried in the leading newspapers of the colonies. It was after all the boldest act of resistance thus far to the Mother Country’s oppressive revenue measures.

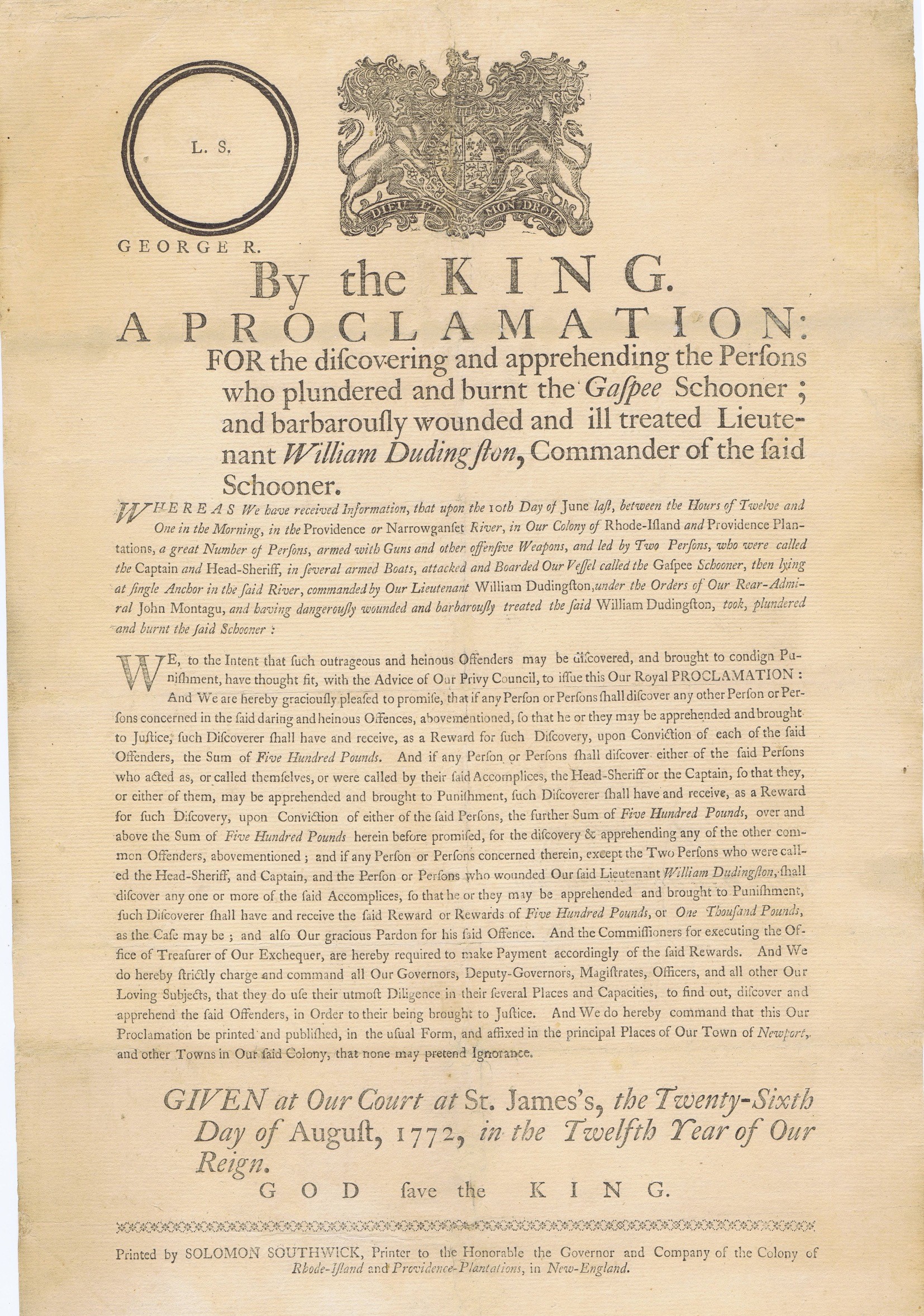

- – Over the next year the British Crown sought to bring the perpetrators to justice. King George III talked of treason being committed. A handsome reward was offered for information leading to the arrest of the perpetrators—£100, later increased, when the first offer of reward provided insufficient, to £500. Those charged with crimes were to be transported to England for trial, away from where the offense occurred, which greatly upset colonials.

- – On August 26, 1772, King George III called for a Royal Commission of Inquiry headed by Rhode Island Governor Joseph Wanton. A number of notables were appointed to serve on the commission: Daniel Horsmanden, Chief Justice of New York; Frederick Smythe, Chief Justice of New Jersey; Peter Oliver, Chief Justice of Massachusetts; and Robert Auchmuty, Judge of the Vice Admiralty Court of Boston.

-

A proclamation on behalf of King George III, August 26, 1772, calling for a commission for the inquiry into discovering and apprehending those involved in the burning of the Gaspee, and increasing the reward for information leading to arrests to £500. This one did not have Governor Wanton’s name on it. Printed at Newport by Solomon Southwick. (Anonymous Collection)

- – Governor Wanton, though he would become a Loyalist in the American Revolutionary War, worked hard to prevent any Rhode Islander from being charged or punished.

- – Many people knew who were responsible for seizing and burning the Gaspee, but no one wanted, or dared, to talk, with one exception. He was Aaron Biggs, an enslaved man. Biggs named names, and for his boldness he was escorted to safety to Boston by a Royal Navy officer. But it is not clear if Biggs had actual knowledge. He may have cleverly used the episode to liberate himself from bondage and join the Royal Navy.

- – The commissioners, after many sessions interviewing numerous people, failed to apprehend or commit anyone on the evidence presented. On June 22, 1773, the commissioners issued their final report to the king and closed the investigation, explaining, “there being no probability of our procuring any further light on the subject ….” No one was ever punished for the burning of the Gaspee.

- – Judge Daniel Horsmanden, used to Royal rule by the King and an elite class of politicians, did not appreciate the democratic elements he found in the colony of Rhode Island. In a letter, dated February 21, 1773, to Lord Dartmouth, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, based in London, he complained, “The government (if it deserves that name) is a downright democracy; the governor is a mere nominal one … a cipher, without power of authority; entirely controlled by the populace.”

- – Lieutenant Dudingston survived his shooting. Since he lost a Royal Navy ship, he had to undergo a court martial. At it, he never mentioned chasing the Hannah and that he had been lured into shallow water which had resulted in his grounding. He claimed that his nineteen officers and sailors faced as many as 250 men. He was acquitted and remained in the Royal Navy, eventually rising in rank to admiral.

The burning of the Gaspee was the most significant act of defiance leading up to the events at Lexington and Concord in 1775, yet it is little discussed or understood. U.S. Representative Francis Baylies of Massachusetts, in referring to Rhode Island during discussion of an apportionment bill on the House floor in 1822, noted, “Has she no claims upon the gratitude of the nation for revolutionary services? – Rhode Island almost commenced the revolution; the burning of the Gaspee was the first open and forcible act of resistance to the authority of Great Britain.”

Post-Revolution, Massachusetts took the main role of defining how the American Revolution began. According to popular lore, there was the Boston Massacre in 1770 and then the Boston Tea Party in 1773, and nothing in between. Of course, that is simply not true.

Stephen Park, when he was a professor at the University of Connecticut, wrote the most accurate history of the Gaspee affair: The Burning of His Majesty’s Schooner Gaspee (Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2016). (And, fortunately, it is not a long book). He noted that a Massachusetts minister, John Allen, first made a strong case for the importance of the Gaspee affair, in a pamphlet entitled, An Oration on the Beauties of Liberty, Delivered on the Annual Thanksgiving Day Sermon, December 3, 1772. Allen called it a direct attack on the British monarchy. Park described the pamphlet as one of the most popular in colonial times. (In the fourth edition of the pamphlet, Allen added a section heavily criticizing the institutions of the African slave trade and slavery).

The cover of a pamphlet by the Reverent John Allen which described the sinking of the Gaspee as an attack on the British monarchy. It was one of the most popular pamphlets of the colonial period. (Photo by Christian McBurney, from an edition held by the Library of Congress)

On June 9, 2022, the date of the 250th anniversary of the start of the raid on the Gaspee, at the headquarters for the Society of the Cincinnati in Washington, D.C., Park gave a lecture on the Gaspee affair. He was preceded by U.S. Senator Sheldon Whitehouse, who is a big fan of the Gaspee affair and agrees that it is very underrated by current history books.

Some historians are starting to get the message. Nick Bunker, in his An Empire on the Edge: How Britain Came to Fight America (New York, NY: Knopf, 2015), has as a major emphasis the Gaspee affair and its importance in the lead-up to the Revolutionary War. The book was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for History.

There is also an outstanding website devoted to the Gaspee affair, with the main author being John Concannon, at www.gaspee.org (click on Archives). (An article by him on the Gaspee will be re-published on this website next week).

The Secretary of State of Rhode Island has also had created an excellent webpage, called “The Burning of the Gaspee.” Many of the documents in the possession of the state archives can be accessed at the website, and there is a virtual tour covering the incident. The website is: https://www.sos.ri.gov/divisions/civics-and-education/for-educators/themed-collections/gaspee. There is even a link for a free poster, with the heading, “Gaspee, The Spark That Ignited the American Revolution.”

Recently, the Rhode Island Historical Society and the Newport Historical Society released a joint publication, called The Bridge, that contained three new scholarly articles on the Gaspee affair.

In comparison one-and-a-half years after the Gaspee’s burning the much-celebrated Boston Tea Party occurred in which patriots disguised as Indians boarded a merchant ship docked at a wharf in Boston Harbor and merely threw casks of tea overboard. The burning of the Gaspee involved taking a ship of the Royal Navy on the seas, shooting its commander, and burning the ship down to the waterline, all accomplished by undisguised raiders. The Boston Tea Party has a commemorative US postage stamp — the burning of the Gaspee does not. WAKE UP RHODE ISLAND!

Recently Robert (“Bob”) Burke, Rhode Island restaurateur, avid state historian, and founder of the Providence Independence Trail, has taken the initiative by sending “cease and desist” letters to key Massachusetts officials, including the state’s governor, ordering them to refrain from claiming that the first shot of the Revolution was fired at Concord and Lexington in April 1775. Burke noted, “This is a clear case of identity theft. Massachusetts stole our identity, and I’m as mad as hell.” Whatever the outcome of this action maybe at least Burke has headed Samuel Arnold’s call to assert Rhode Island’s indisputable place among the earliest in Council and the foremost in action.

Burke and others have organized a plebiscite that is currently being held, from June 9, 2022 to July 4, 2022, to put the matter before citizens to vote the choice of Rhode Island or Massachusetts. The website where you can (and should!) vote is: www.justaminuteman.com.

NOTES

[1] Several years after the burning of the Gaspee, the HMS Rose patrolled Narragansett Bay. Its commander, Captain James Wallace, in an imperious and overbearing manner similar to that employed by Lieutenant Dudingston, often threated to bombard Newport and Bristol. At one point Wallace wrote to Abraham Whipple warning him, “You, Abraham Whipple, on the 10th of June, 1772 burned His Majesty’s vessel, the Gaspee and I will hang you by the yard-arm.” Whipple responded, “To Sir James Wallace, Sir: Always catch your man before you hang him.” [2] Sheldon S. Cohen, Commodore Abraham Whipple of the Continental Navy (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2010). [3] The Rhode Island American of August 13, 1824, noted in its article “Olden Times” in referring to the burning of the Gaspee, “It has, however, scarcely been noticed in the histories of that period, and while Massachusetts and Virginia have been contesting the question, which of them gave the first impulse in the American Revolution, the claims of Rhode Island have not been thought of.” [4] Samuel Arnold, History of the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, 2 volumes (New York, NY: D. Appleton & Co., 1859). [5] Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 39, No. 2 (1952), pp. 233-256.