The use of lightships as navigation aids began in England with the shipping of coal from Newcastle to London. With disturbing frequency, ships foundered on the rocks and shoals at the entrance to the Thames River. The first lightship, the Nore, was placed in service in 1732 by David Aury and Roger Hamblin, shippers who had lost some vessels. They, in turn, levied tolls from other ships for maintenance of the Nore. They later sold most of the rights to Trinity House, the famous protector of British commerce, but continued to collect tolls for another 61 years.

By 1870, 55 lightships dotted the Irish and British coasts. By comparison, the United States, at the height of its lightship fleet in 1939, maintained 30 stations. In the U.S., the first one was placed off Willoughby Spit, Virginia, near the mouth of Chesapeake Bay in 1820. The total number of lightships placed in service in the U.S. was 43, which included 9 relief ships and 4 ships out of commission. In March 1985 the last U.S. lightship, Nantucket WLV-612, was retired. As with other retired lightships, it was replaced by buoys or fixed towers.

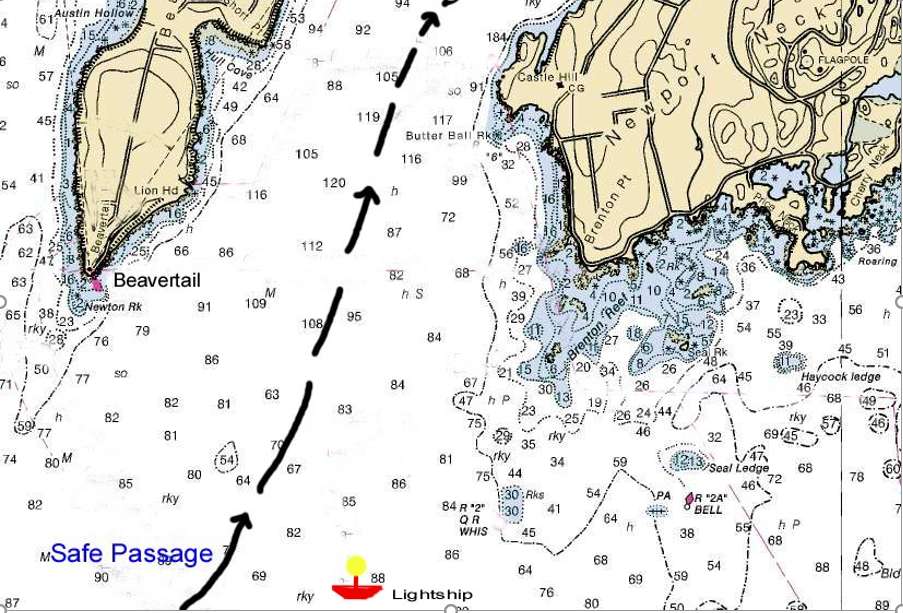

This is the safest route for a vessel to follow into the East Passage of Narragansett Bay. The location of the Brenton Reef lightship is also shown.

Lightships and lighthouses operated under the direction of the Lighthouse Service within the U.S. Treasury Department until 1903. Then the Commerce Department’s Bureau of Lighthouses took over until 1939, when both lightships and lighthouses were transferred to the U.S. Coast Guard.

Rhode Island’s role in maritime commerce continued into the twentieth century. Vessels loaded with cargo entered Narragansett Bay, dropped off the cargo at a port, and departed the bay. Large sailing vessels from around the East Coast and across the Atlantic frequently entered Narragansett Bay. Coastal schooners were the pack horse of commercial traffic. U.S. Navy warships also used Narragansett Bay. With all this maritime traffic came the need for navigation aids such as lighthouses, buoys, and dredged channels to provide safe passage. Supplementing these improvements, two locations, one in Mount Hope Bay (Hog Island Shoal ) and the other at the East Passage entrance of Narragansett Bay (Brenton Reef) were selected by the U.S. Lighthouse Establishment to add anchored lightship vessels as warning beacons of underwater hazards.

Brenton Reef Lightships

The dangerous reef of rocks and shoals called Brenton Reef off Brenton Point in Newport has for more than two centuries worried seamen. The reefs are located two miles due east of Beavertail Lighthouse on the southern tip of Conanicut Island (Jamestown). They extend southwest about one-half mile from Brenton Point. The reefs expose themselves only at very low tide and only when there is a heavy sea or swell. They are the hidden dangers that have taken both lives and ships. Although Beavertail Lighthouse provided the beacon for navigators to make the initial land approach by marking the southern end of Conanicut Island, the reefs, which lie on the other side of the East Passage to the east of Conanicut Island, remained a hazard.

As shipwrecks and groundings continued on Brenton Reef, it became apparent that a prominent navigation aid needed to be placed off the reef extending from Brenton Point. The solution was a lightship strategically placed so that an approaching vessel into the East Passage of Narragansett Bay could follow a deep channel course between Beavertail Point and the anchored lightship, safely away from the underwater rocks of Brenton Reef.

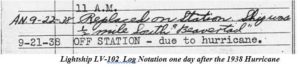

In 1851 appropriations were made to build a “Light-a-Boat” to be placed off Brenton Reef to warn incoming ships of the hazard. A special vessel was constructed in Newport and launched in 1853. This two-masted sailing vessel equipped with a single lantern of 8 lard oil lamps was designated LV-14 and was the first of four lightships assigned to Brenton Reef over a 109-year period. They were placed in deep waters where incoming vessels in transit could pass them close aboard and use the lightship as a point of entrance or departure in and out of Narragansett Bay. Each vessel bore the letters BRENTON REEF or BRENTON on both sides of the hull. At times another vessel marked RELIEF replaced the BRENTON when it was required to proceed into port for maintenance, repairs or upgrading. RELIEF, based in Boston, served lightships from Maine to New York.

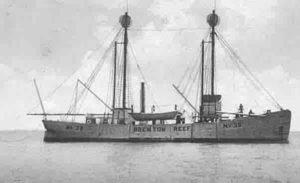

Only four vessels were permanently assigned to lightship duty to mark Brenton Reef. The early ships were sailing vessels. The last one, LV-102, had a special steel whaleback design and was painted bright red, the color characteristic of more recent designs. It also included a radio beacon. Only two ships of the same design were built. Her sister ship, LV-101 is now a museum in Portsmouth, Virginia.

Brenton Reef lightships were always in view from the mainland at Narragansett, Brenton Point in Newport, and from Conanicut Island. They lay anchored less than two miles offshore and with their markings painted on both sides of their hulls easily identified.

The following is information on Brenton Reef lightships. Shown are their designations, lengths, periods of service, and dispositions.

LV 14, 91 feet, 1853-1856, sold for $615.

LV 11, 104 feet, 1856-1897, sold in 1925.

LV 39, 119 feet, 1897-1935, sank being towed to yard

LV 102 (WAL 525), 102 feet, 1935-1962, sold in 1965 and used as a crab processing vessel in Alaska

Hog Island Shoal Lightship

The second lightship in Rhode Island was located off the north end of Aquidneck Island where Mount Hope Bay joins Narragansett Bay. It was located where the present Hog Island Shoal Lighthouse is situated, less than a mile southwest of Mount Hope Bridge. This vessel was used to mark Hog Island Shoal, which extended south from Hog Island, hampering vessel traffic in and out of Mount Hope Bay.

Initially, a dimly lit lightship was placed on the southern end of the shoal by the Old Colony Steamboat Company, which ran passenger ships from Fall River to Newport and New York City. The light was inadequate, and in 1886 the federal government provided an old lightship to serve at the location. It was LV-12, previously used at Fishers Island Sound off the Connecticut shore. LV-12, as other lightships, displayed the name of its location painted on both sides of the hull and when on station showed a fixed white light. Ironically, her first captain at Hog Island Shoal, Augustus Hall, for unknown reasons committed suicide by jumping overboard.

LV-12 was a 72-foot, two-masted schooner built 40 years earlier. She remained on station until 1901 and was nearly 70 years old when sold in a decrepit condition for $360 in 1916.

In 1901 Hog Island Shoal Lighthouse was constructed and took over as the active navigation aid. In 2006 the lighthouse was automated. A structure sitting on a shoal was then considered excess and auctioned off for $165,000.

Lightship Duty

Lightship duty was not a highly desirable position for a seafaring man. The turnover rate of officers and crew was very high. These were ships that never sailed and were always exposed to the worst weather. They were also the most prone to be hit or sunk by a passing ship. Ships intentionally steered for the lightship’s position to visually confirm their own location. During fog they homed in on the lightship’s radio beacon, then passed close aboard using the lightship as a point of departure to their next waypoint.

In August 1905, Brenton Reef LV-39 was struck by the massive battleship Iowa. Fortunately, no lives were lost and the damage was not severe. The accident carried away part of the lightship’s stem and caused damage to her head stays.

The danger increased when lightships were equipped with radio transmitting beacons. Ships would tune their radio direction finders directly on the azimuth bearing emitted from the lightship. Without range information, they had to keep a sharp lookout and veer off when the lightship came into view. In heavy fog visibility could be limited to a few feet thereby creating even more danger.

The danger to lightship sailors was real. On May 15, 1934, LV-117, occupying the Nantucket Shoals Station in a dense fog, was struck by the RMS Olympic and sank on station with the loss of seven crew. On January 6, 1934, the United States Line SS Washington came within inches of ramming the replacement LV-117 on the Nantucket Station. The liner scraped the lightship’s side, shearing off davits, a lifeboat, and radio antennas. No one died in this incident.

An earlier incident happened during World War I. On August 6, 1918, the first American lightship was sunk by an enemy submarine. LV-71 was lost on the Diamond Shoals, twelve miles off of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. Her crew took to their boats and reached shore without injury.

Don Goguen, MKCM (ret), was a Coast Guard crew member of the last lightship at Brenton Reef. He describes some of his experiences below:

I served aboard the Brenton Reef from November 1959 to April 1961. She was designated as WAL-525 at that time. She was built in 1916 or 1919 as I recall. This was my first duty station as a young 17-year old right out of boot camp. I was assigned to deck duties as a seaman apprentice. I did not care for the tasks of chipping and painting too much, but did qualify to stand watches on the radios and radio beacon, but can’t remember specific equipment types.

An opening came up for a fireman in the engine room. I asked to transfer and earn the engineering rate. I can remember the power plant to a certain extent. The original plant was powered by steam and some of the deck equipment such as the windlass was converted to electric power. I don’t know when the ship was converted to diesel.

The main engine was a Cooper Bessemer 6 cylinder diesel, direct reversible type. The engine was stopped and restarted by shifting the camshaft to run in the opposite direction for astern operation. The two DC generators were Hercules diesels and small converters were used for the AC equipment on board. We had few AC powered equipment for that reason.

The movie projector was the most important equipment next to the radar, according to the captain. I was also the movie projector operator and got my butt chewed when the film broke.

The generators were operated from 0600 to 2400 and the ship’s electrical supply came from storage batteries from 0000 to 0600. The batteries were charged during the day. The radar needed AC power, so if the fog set in during the night, we would have to go to generator power. This would also require the fog horn to be activated. Two International Harvester diesel air compressors were used for the fog horn. My normal watch was from 0600 to 1500 so if the fog set in between 0000 and 0600, I would be awakened to lite off [to start] the generator, air compressor and switch the electrical load. The other engineer and I would then stand six hours on and six hours off while the fog was in. I think the requirement for turning on the fog horn was if we could see Montauk Point on Long Island or not.

The scary part of sitting in the fog was watching the big ships hone in on our beacon and see the blips on the radar as they came close by. Sometimes they got so close that the watch would alert the crew and we would get life jackets adorned.

The normal duty time spent on board was two weeks on and one week off. Not bad duty. The total crew was 14 and we usually had 9 on board at any one time. I rotated duty on board with two other engineers. I was stationed at Castle Hill Station when the ship was replaced by the tower. I think that was in1962, I’m not sure.

The only outstanding event I can remember was hurricane Donna in 1960. All lightships on the east coast were given the choice of staying on station or going to safer haven by the District Commander. Our BMC, who was in charge at the time, decided to ride it out. The only other lightship to do so was the Portland as I was informed by our radio watch. We put both mushroom anchors out and ran the main engine ahead. We still got pushed four miles off station. Nasty little ride, green water breaking on the pilot house. It made a sailor out of me. I tied myself to the engine room ladder so I could monitor the engine gauges and just ate crackers. The only time I moved was to fill the fuel day tank and make a head call. I volunteered to stay on watch because the ride was better low in the engine room.

Got a little rest when the eye of the storm passed by. The older guys said it was the eye, what did I know? We lost the radar antenna, both life boat covers and had one port hole staved in on the port bow. The crew patched the hole and mended two crewmen that were hurt by the storm. The storm got just as bad, if not worse after the eye had past. This time I watched sea water spray down the vent pipes into the engine room. A couple of seamen held a line around my waist so I could go out on deck and turn the vents. Anyone that didn’t get a little sea sick in that storm is full of @#%&&&&. After the seas let up a day later, Castle Hill Station picked up the injured crew members. There were a few broken bones as I can recall.

Well that’s about the only sea story I can remember from the days on the little red boat.

Brenton Reef Tower

As the cost of operating, manning with crew, and maintaining lightships on station continued to rise, the Coast Guard was also faced with replacing the vessels, some of which were more than fifty years old. Gradually, all were phased out, and fixed unmanned towers called “Offshore Light Towers” were placed at some lightship locations.

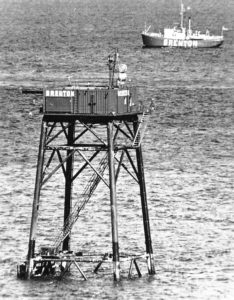

Brenton Reef Tower (or the Texas Tower, as it was nicknamed) was constructed in 1961, with steel piles driven into bedrock 80 feet below the water’s surface. LV-102 hovers in the background.

Brenton Reef Tower, or the Texas Tower, as it was nicknamed after the early oil rigs in the Gulf of Mexico, was constructed in 1961 on top of four 30-inch diameter red steel piles in 80 feet of water. The legs were driven 25 feet into bedrock. It was located 1 and 1/2 miles southeast of Beavertail Light as a replacement for the lightship. It too had the letters BRENTON painted on each side. The unmanned tower was powered via an undersea cable from the Beavertail Light Station. It retained an emergency battery backed-up light in case of a power failure. Placed into automatic operation in 1962, its characteristics were a 1.2 million candlepower white light provided by a double-ended type DCE-36 Rotating Airport Beacon showing 2 flashes every 10 seconds, visible out to 16 miles. The tower was also equipped with an automatic fog signal, sounding a group of 3-second blasts every 60 seconds when activated and directed away from the Newport area.

In 1982 the Coast Guard considered discontinuing the use of the tower and solicited comments from users. Local fishermen and the recreation boating public objected, stating it provided a valuable visible mark when entering Narragansett Bay. The decision was delayed on two occasions, but operational costs and the need for extensive repair of the corroding underwater legs were prohibitive. Repairs were estimated to cost over $500,000. Cracks appeared in the visible areas of the legs, which showed extensive corrosion. The tower continued to provide service until March 1989, when the Coast Guard announced the installation of a new 20-foot high Narragansett Bay entrance sea buoy placed farther to seaward. This red-and-white sea buoy is designated NB for Narragansett Bay Entrance. The buoy’s main characteristics are a 4-second flashing light emitting the Morse code letter A and a horn and a radar transponder beacon that transmits the Morse code letter B back to a ship when interrogated by a ship’s radar.

The establishment of the sea buoy ended 136 years of marking Brenton Reef with a navigation aid.

Radio Beacon

The RDF radio beacon (type D) transmitting on the frequency of 310 kilocycles located on the Brenton Reef tower was transferred to the Beavertail Light Station in 1989, where a vertical ground plane antenna was erected on the grounds behind the keeper’s house. Copper radials of size #8 wire, each 100 feet in length, were buried every 3 degrees from the antenna to act as an artificial ground counterpoise. The Morse code signal identifier B used previously for the word Brenton was retained and used for the word Beavertail. Point Judith Light Station’s radio beacon range was extended at the same time, providing radio coverage out to Buzzards Bay. The range of the radio beacon for Beavertail essentially added 14 miles of additional range over the light. The radio beacon is no longer operational but the radio tower still stands and has been used by ham radio operators during special lighthouse commemoration events.

[Banner image: Lightship LV-102 was stationed off Brenton Reef from 1935 to 1962]

Bibliography

Robert Bachand, Northeast Lights, Lighthouses and Lightships, Rhode Island to Cape May, New Jersey (1989)

Jeremy D’Entremont, The Lighthouses of Rhode Island (Commonwealth Editions, 2006) (Hog Island Shoal)

Department of Commerce, Lighthouse Service Records, National Archives, Waltham, MA

Letter from Donald Goguen, MKCM USCG (ret) WAL 525, to Varoujan Karentz, April 15, 2001. Author’s Collection.

Varoujan Karentz, Beavertail Light Station (Book Surge Publishers, 2008), chapter 8

National Park Service, Lighthouse Keepers in Nineteenth Century (NPS Brochure, 2002)

United States Coast Guard Library, New London, CT

United States Coast Guard Historic Light Station Information Web Site 2001

United States Lighthouse Board Report, 1894 and 1905

US Lighthouses, www.uslighthouses.com

USCG Lightship Sailors Association, Beverly Massachusetts