[From the editor: The following first installment of a two-part article is.” from a chapter in a book written by Edmund Pearson, Murder at Smutty Note and Other Murders (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1926). Sarah Maria Cornell, a factory worker, on a chilly day in December 1832, was found dead and pregnant in northern Tiverton under suspicious circumstances, and for several reasons the Reverend Ephraim Avery, a Methodist preacher then residing at Bristol, was charged with murder and tried at Newport. For one, Cornell apparently left behind a letter stating that “If I should be missing, inquire of the Rev. Mr. Avery, of Bristol.” Second, Avery admitted he had been walking in Tiverton around the time of the murder. What ensued was one of the longest and most sensational trials in Rhode Island history. Some 239 witnesses testified at the trial, with many of them speculating about the sexual history and proclivities of the victim, Sarah Maria Cornell. This kind of speculation would not be permitted in a trial today. This piece was written in 1926 and, accordingly, has a certain amount of bias, as well as hesitancy to discuss openly the speculations about Maria Cornell’s sexual past. The article also did not adequately cover testimony regarding Cornell’s reputed unstable mind. In addition, the article does not mention that the Methodist Church funded Avery’s high-priced legal defense team. I have made a few omissions from the article that cover material extraneous to the trial or that have obscure references. Still, Pearson’s article is well done. This first installment covers material prior to the Newport trial and verdict. For a modern and excellent history of this trial, which also gives a fine background of Rhode Island at the time and the lives of New England mill workers, many of whom were women, see Bruce Dorsey, Murder in a Mill Town: Sex, Faith, and the Crime that Captivated a Nation (New York: Oxford University Press, 2023).]

Early in the morning of the shortest day of the year, December 21, 1832, a farmer named John Durfee of Tiverton, Rhode Island, was driving his team through a field, a short distance from his house. In a stack yard nearby, he observed the body of a woman hanging to a stake—one of those used for the support of a stack of hay. He went to her, parted her hair which covered her face, and saw that beyond all doubt she was dead.

As an outside garment she wore a long cloak; her hat was one of the kinds called a calash. She wore gloves, but her shoes were off, and were standing on the ground about eighteen inches to the right; on the other side of her lay her handkerchief. She seemed to have died from hanging; a cord was knotted about her neck and attached to the stake. But her knees were bent under her, and her toes touched the ground; it appeared that the cord must have slipped, after death, and let her down to the earth.

Durfee called his father and two other men. With some difficulty, they cut down the body. The Coroner was then notified. Before he impaneled a jury and began his investigation, other persons had arrived and recognized the dead woman. She was Sarah Maria Cornell, a factory employee of Fall River, and about thirty years old. Mr. Durfee went to her boarding place, Mrs. Hathaway’s in the village of Fall River, to get her trunk and clothes, as it was proposed to bury her near the place of death. The landlady said that, rather out of her usual custom, Miss Cornell had left the house the night before, about dusk, remarking that she was going to Joseph Durfee’s and that she would return before nine o’clock. She was in good spirits, and not like a person bent on suicide. With the trunk, which she delivered to Mr. Durfee, was a bandbox, and this was found to contain some letters. Upon the evidence of all of these facts, and some information furnished by a doctor, whom the dead woman had consulted, the coroner’s jury rendered a verdict the same day the body was discovered. This was that she had committed suicide, “and was influenced to commit the crime by the wicked conduct of a married man.”

Sarah Maria Cornell worked in a variety of factories in Rhode Island, Connecticut and Massachusetts. This young woman is shown working as a spinner at Interlaken Mill, Arkwright, Rhode Island. She had worked there one year. The photographer thought she was just twelve years old and wrote that she “had a hectic flush caused by the warm, close atmosphere.” (Lewis Hines Collection, Library of Congress)

Soon after the inquest, she was buried, but two days later a small slip of paper was found in her bandbox; on it was written in pencil the words:

If I should be missing, inquire of the Rev. Mr. Avery, of Bristol—he will know where I am. Dec. 20th. SARAH M. CORNELL.

Public opinion was instantly aroused against Mr. Avery, a Methodist minister of Bristol, Rhode Island. He was almost unanimously condemned, without further evidence. The body was exhumed; there was a second inquest, and this time a verdict of murder. On December 23d, Mr. Avery was arrested. Christmas, at that period in New England, was not celebrated as it is today, so there probably seemed nothing incongruous in the fact that his examination before two justices of the peace began on December 25th. It continued for fourteen days, opening with a long statement by the accused man, as to his actions on December 20th, the day of Miss Cornell’s death, and as to his acquaintance with her.

By this statement, it appeared that Mr. Avery, on the afternoon and evening of the 20th, had been on a long and lonely walk. If it was as innocent an excursion as he solemnly avowed, it was, nevertheless, one of the unluckiest rambles in which a gentleman ever indulged. It is quite possible, even in that Northern climate, and at that season, to find a perfectly good day for a long walk. But in this century, at all events, a person who willingly walks five or ten miles at any season whatever, is suspected of incipient lunacy, if not of graver offences. To stew nearly all day in the house, and then to be conveyed somewhere in an automobile is considered rational conduct; but the walker, if he is not himself murdered by an automobile, is lucky if he is not charged with some felony. Mr. Avery, even in his time, had the worst possible fate. To understand his trip, and its significance, there must be a brief geographical diversion.

As many of us do not live, or spend our summers, on Narragansett Bay, the fact may be forgotten that Rhode Island, the actual island of that name [i.e., Aquidneck Island], is in the bay, and that it forms but a small part, perhaps a twentieth of the State of the same name. The State used to be called Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. The latter part of the name has now gone by the board; perhaps the fact that Rhode Island [i.e., Aquidneck Island] contains the city of Newport is the reason why it has imposed its name upon the much larger region which is on the mainland. Mr. Avery’s town of Bristol is on a peninsula which stretches into the bay, nearly touching the island of Rhode Island at the northern end. To the east of the island, across the Sakonnet River, lies a small fragment of the State, containing the village of Tiverton, where Sarah Maria Cornell had died. North of Tiverton, and only about half a mile from the spot where her body was found, is the boundary line between the State of Rhode Island and Massachusetts, and here, on this line, is the city, then the village, of Fall River, where she lived and worked. If one had occasion to go from Bristol to Tiverton—in 1832, at all events—the easiest course would have been to cross to the island of Rhode Island by the ferry [south of Bristol], thence across the island, two miles broad at this point, and again to the mainland by way of Howland’s or the Stone Bridge.

Mr. Avery took the first of these steps, but, according to his statement, not the second. That is, he crossed by the ferry to the island of Rhode Island, and there, after a long walk, he stayed all night. It was not an impossible day for a walk; it had been cold and rather blustering in the morning, but grew warmer at noon, and was then two degrees above the freezing point: certainly a mild day at this season. Testimony was produced that he was in the habit of taking long walks, being gone half a day or more, and returning at night.

On December 20th, so he testified, he left home and crossed by the ferry at about 2 P.M. He had two objects in visiting the island. First, he had heard that Rhode Island coal was cheap in price, and that it formed a good fuel when mixed with other coal. He had talked with a neighbor in Bristol about it; he talked with another man on the ferry, as he went to learn about the coal, and perhaps to buy some of it. Second, soon after his appointment to Bristol, his father had written to him that he had been stationed in Bristol during the Revolutionary War; that with Sullivan’s expedition he had been on Rhode Island, where he had admired the scenery, and had made the acquaintance of certain families. He asked his son to discover if, after so many years, members of these families survived. He also inspired the younger Avery to wish to view the battlefield where his father had been in action.

With these two objects, the reverend gentleman wandered about the island all the afternoon; lost his way more than once; miscalculated his distances; and was overtaken by night. When he reached the ferry again, it was long after dark—four hours after, at least, since it was nine o’clock. The ferryman refused to take him across (the width of the ferry was nearly a mile) but offered to put him up for the night. This offer he was glad to accept, and he did not cross to Bristol until next morning. At no time, he said, after he landed on the island early in the afternoon of December 20th, did he leave it until the following morning. He did not cross the Stone Bridge to the Tiverton side; was not in Tiverton that day, nor in Fall River; nor did he see Sarah Maria Cornell, nor [did he have any] part in her death.

The Belfry Mill at Georgiaville, Rhode Island, built in 1813. Sarah Cornell worked in mills similar to this one. (Providence Public Library Digital Collections)

Notwithstanding Mr. Avery’s sacred calling, the public in general, and the folk of Fall River in particular, were disposed to receive this narrative [with a jaundiced eye].

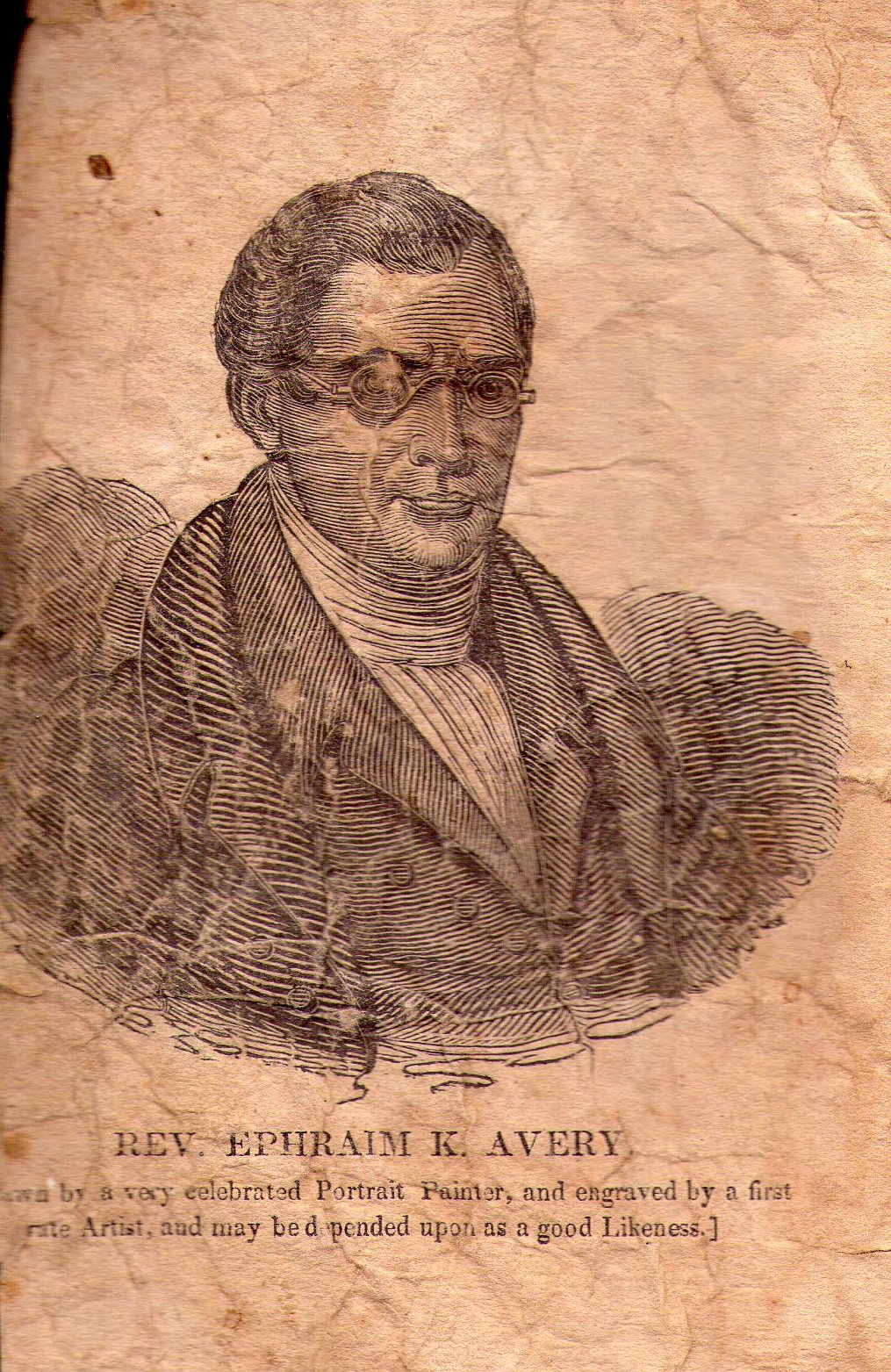

[ ] . . . [P]ublic gossip, newspaper writers and pamphleteers, began to represent Mr. Avery as a combination of Casanova and Sixteen-String Jack [a reputed English gentleman highwayman who was executed in 1774]. His first wife, they said, had died of a broken heart as a result of his unkindness and infidelity—although he was then living, in apparent amity, with his first and only wife, who seems to have adhered to him during all his misfortunes.There were ten years of his life for which he could not account: during this period, he had been a pirate in the West Indies. So ran a story, which rather unnecessarily grieved his friends. Both he and they failed to enjoy its drollery, as you and me, my reader, even gifted as we are with an exquisite sense of humor, might fail to enjoy the malicious gossip of a small town, if we lay in a dirty jail, under [the risk of being charged] of murder. What art could do to please the populace and vex Mr. Avery, is shown in the accompanying caricature, “A Very Bad Man,” which was apparently published as a separate sheet, not part of a book. I am sorry that I can give no information about the play on the subject of Mr. Avery and Miss Cornell, which was given at the unlucky Richmond Hill Theatre, in New York, and is said to have been revived “again and again.”

There arose, of course, very early in this investigation, the question why the unfortunate factory operative, a few hours before her death, should have written the enigmatic message about the clergyman of Bristol. To explain this, the prisoner now addressed himself. He had been acquainted with her for more than two years: since July 1830. He then lived in Lowell, Massachusetts, where Miss Cornell applied to Mrs. Avery for employment. The minister’s wife declined the offer; she was not pleased with the girl’s appearance—and if the portrait of her is a good one, Mrs. Avery was justified. Later, Miss Cornell asked her pastor, Mr. Avery, for a certificate of regular standing in the Methodist Church, as she was going to a camp meeting at Eastham, and also to visit friends in Connecticut. The certificate was given, conditionally, as the pastor had heard the young woman was “accused of profanity.” After a bit, she came back to Lowell, keeping the certificate. Mr. Avery was soon pained to hear, from her employers, that profanity was the least of her offences, and she finally confessed to him that she “had done wrong and had been a bad girl.” His advice to her probably conformed with the practice and rules of his church: she must stand trial, would probably be expelled, but could, in due time, on sign of reformation, again be received into communion. He tried to recover the certificate, which she said she had lost.

She was next heard of in Dover, New Hampshire, where she had obtained admission to the Church by use of the Lowell certificate. Mr. Avery wrote to the Rev. Mr. Dow, the Methodist minister at that place, informing him of the causes for which she had been expelled in Lowell; to these faults, he said, it was now charged that she had added theft [she admitted stealing some cloth from a store at Providence].

Miss Cornell moved about the State, from one town to another. In one of them she accused a physician of so far forgetting himself as to make an attempt against her chastity. She continued to write to or call upon Mr. Avery, asking for his forgiveness.

At a camp meeting in Connecticut, she was said to be present, and although he did not speak to her, “the brethren were cautioned of her,” at his suggestion. Finally, she turned up in Fall River, where one night, after a meeting, she stopped Mr. Avery on the street—he was with two or three ladies at the time—and begged him not to injure her. He had exposed her and ruined her reputation, she said, in Lowell and Dover; she hoped he would persecute her no further. He said that he had no intention of wronging her in any way; her reputation in Fall River depended on her conduct there. In fact, he had already been questioned by his Fall River colleague, the Rev. Mr. Bidwell, about the woman, and had told him, as he was bound to do, about her expulsion in Lowell. After that, Mr. Avery had preached once in Fall River, and had noticed Miss Cornell in the congregation. He had never seen her again.

The effect of all this, of course, was to present the picture of a genuinely unfortunate woman [ ] who had led a more or less disorderly life, punctuated with attempts at reform. These attempts may have been partly sincere, and partly the result of realizing that her livelihood and her social life depended upon her church membership. There was in it all a suggestion of a mild case of the delusion of persecution: she looked upon Mr. Avery as the beginning of all her misfortunes. When she found herself in an embarrassing situation—for the autopsy had revealed pregnancy—and she was resolved upon suicide, she left behind her the note with Mr. Avery’s name in it—either for revenge or for some motive unknown.

These were the conclusions which one might draw from Mr. Avery’s statement before the magistrates at Bristol. He was represented by three lawyers; numerous witnesses were called on both sides. The suggestion of the officers of the law, and the widespread belief as to his acquaintance with the dead woman, and his knowledge of her death, were quite different. This unfavorable view of him will be explained later. The weight of the evidence against him at Bristol does not seem great, and one is tempted to agree with his friends that if it had not been for the scrap of paper, of doubtful import, found in the bandbox, suspicion against him would never have arisen, and proceedings would not have commenced. The two magistrates, after listening to testimony for fourteen days and without consulting together, arrived at the same conclusion. It was that no sufficient cause had been shown to hold the accused for the murder. One of the justices delivered a long opinion—a thoroughly sensible discussion of the evidence. Mr. Avery was, accordingly, released.

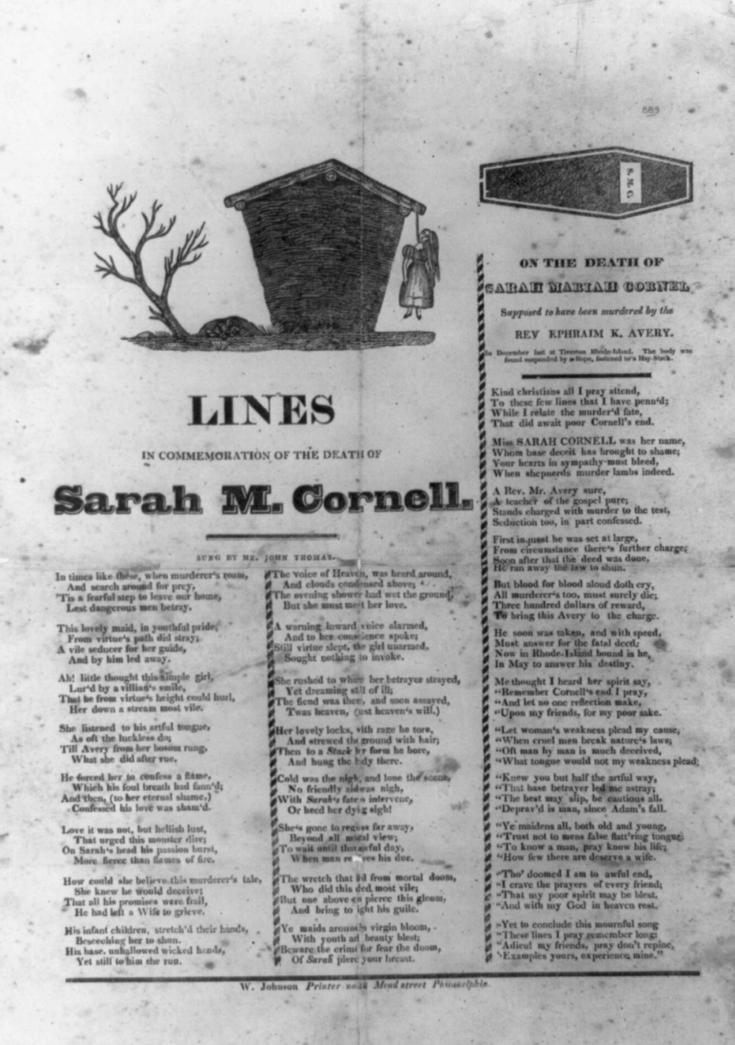

An anti-Avery broadsheet made by a Philadelphia printer containing a poem on the murder of Sarah Maria Cornell. Note the image of her hanging from her coffin. The title in the upper right states: “On the Death of Sarah Maria Cornell. Supposed to have been murdered by the Rev. Ephraim K. Avery. In December last in Tiverton, Rhode Island. The lady was found suspended by a Rope, fastened to a Hay-Stock.” (Library of Congress)

The fury of a large number of the people was merely inflamed by this decision. Whether Methodists were especially unpopular at this time, or what else may have been the cause, is not clear. The two magistrates, so went the gossip, were both Masons, and Mr. Avery also was a Mason; therefore the poor, betrayed lamb, Miss Cornell, was to go unavenged, while the ravening wolf, her destroyer, would walk the earth unwhipped of justice. [ ]

Indignation meetings were held by the citizens of Fall River and Tiverton, and means were discussed for procuring another warrant against Mr. Avery. He was threatened with violence; mobs gathered outside his house, and he and his friends decided that his life was in danger. By the advice of his friends and of his counsel, he took what now appears to have been the unwise course of flight. He disappeared from the State. It always seems best, of course, for a man to stay and “face his accusers,” but when the accusers come in a mob, bent on violence, exactly how he is to face them with any satisfaction is a little hard to explain. . . . [ ] Mr. Avery’s flight naturally had the result of confirming the general opinion of his guilt.

Now appears Harvey Harnden, sometimes called Colonel Harnden. He was armed with a kind of warrant or writ–peculiar and complicated in its nature—and set out on his travels to find the fleeing minister. Mr. Harnden voyaged far into remote and wild districts of Massachusetts and New Hampshire . . . [ ] He had to show great tact and discretion; keep his own counsel and remember at all times that he represented the law and the offended dignity of the people of Rhode Island. For something like five or six days, he was practically cut off from communication with all mankind—at least of his own State —and he did not even write to his wife. When he did come back, he had very naturally become a figure of world-wide interest; he had penetrated the lairs of the Methodists, dragged forth and brought one back, alive.

So, he satisfied the universal curiosity by writing his “Narrative of the Apprehension . . . of the Rev. E. K. Avery,” which had an enormous success, and almost immediately went into a second edition.

Mr. Harnden trafficked with High Sheriffs, Governors, and Secretaries of State. He picked up the trail in Pawtucket but lost it in Attleborough. He made his inquiries in Wrentham, Walpole, and Dedham. From, the last place, he proceeded to Boston, where he stayed at the Broomfield House, kept by Preston Shepherd, Esq. Here he declined to register his name but sought an audience of Governor Lincoln of Massachusetts. Some stately business being concluded, he continued, with his assistant, Mr. Allen, to Woburn, where Mr. Allen “was taken unwell.” He left him to take the stage in the morning, while he pushed on. At Billerica (pronounced Bill Ricker) his horse became lame. He left him and took another. He arrived in Lowell, and here, he began to suspect, the natives were hostile. He sensed—as the novelists say—he sensed opposition. This, however, only increased his determination, and with the aid of the High Sheriff, he ran down a wealthy citizen who was suspected of being a strong partisan of Mr. Avery. He confronted this man, apparently in his own home, and after the High Sheriff had withdrawn, but in the presence of other witnesses, he delivered to the unnamed man of wealth an oration. I will give it, as a sample of Mr. Harnden’s style in face of the enemy:

“On such a day you were in Bristol; you left there with two ladies in a carriage, drawn by two white horses; you stopped in Attleborough at the tavern kept by Mr. Newell, and when you there stopped, Ephraim K. Avery was in the carriage with you. You there called for half a bushel of oats and gave them equally to your horses; you remained there about one hour. When you were ready to start, it was discovered that there were oats remaining before the horses. They were taken, tied up in a handkerchief, put into the carriage, and when you left, Ephraim K. Avery was with you. You next stopped in Walpole, near a public house. You and Mr. Avery got out of the carriage; neither of you went into the house; you then started again, and Ephraim K. Avery was with you. You next stopped at Mr. Sumner’s tavern in Dedham, where you put up for the night; and at that time Ephraim K. Avery and two ladies were with you. A private room was there called for, into which you went. The ladies wished a room, which they could lock themselves into for the night, and requested that you might be shown where you could rap in the morning to awake them, as you designed to start early. You were shown a closet in which you might rap to awake them. You left that place about the dawn of day, the next morning, and when you left, Ephraim K. Avery was with you.”

The terrified citizen, reduced almost to a jelly from fear, begged to speak with this inexorable agent of justice, for a few minutes alone. There followed a long interview, and the information was drawn from the quivering wretch that he believed that Mr. Avery was in Rindge, New Hampshire.

View of Tiverton from the height on which stands Fort Barton, circa 1890 (Providence Public Library Digital Collections)

There followed two days of negotiation with the Governors of Massachusetts and New Hampshire; legal delays and correspondence; drawing up of maps and plans of campaign; interviews with deputy sheriffs, county squires, and itinerant bakers; and the assumption of a disguise by the indomitable Hamden. At last, he found Mr. Avery, standing behind a door in a house in Rindge, where the family had given him a refuge. Mr. Avery showed a little emotion at this second arrest, but no especial sign of fear. Without the use of shackles, chains, or manacles, and with no opposition, Mr. Harnden conveyed his prisoner back to Rhode Island. The journey seems to have taken nearly a week, and at the various taverns where they spent a night, Mr. Avery was called upon by some folk who were curious to see him, but also by a good many friends and sympathizers.

A contemporary drawing of the Reverend Ephraim K. Avery, “drawn by a very celebrated Portrait Painter, and engraved by a first rate Artist, and may be depended upon as a good Likeness.” During his trial in 1833, there was a strong national demand for his likeness (Russell J. DeSimone Collection)

[The next and second installment: the murder trial at Newport and the verdict.]