As the stagecoach disappeared from the urban scene with bittersweet memories for drivers and passengers, it was replaced temporarily by the next stage in the evolution of local mass transit—the omnibus. The “bus,” or “buss,” as it was popularly known, proved to be a crucial link to urban mass transit. The name was actually coined in France where this type of service in the congested European capitals predated American experiments by a decade.

Omnibuses first appeared in the U.S. in New York City in the 1830s. This one on Fifth Avenue is from 1890 (New York Public Library Digital Collections)

New York City hosted the earliest omnibus in the United States in the late 1820s. These vehicles were modified stagecoaches with back entrances for urban passengers on short fixed routes. They resembled circus wagons and could seat twenty-five passengers on longitudinal benches. Most of the conveyances were decoratively painted, often with patriotic designs. Owners lettered the sides with whimsical names like antique vanity plates. In 1831 John Stephenson, a coachmaker by trade, designed and equipped a sturdy model for trips on Broadway in New York City. By 1835 a fledgling fleet there grew to one hundred and multiplied to almost 700 by 1853.

Rhode Island Historian Robert Grieve mentioned that after the demise of long distance stages, “omnibuses were very generally used for local transportation.” Another twentieth century observer Welcome Arnold Greene described them as “furniture wagons” with a design peculiar to Providence. These “low gears” with upholstered seats became the era’s “excursion wagon” of choice.

The reign of the omnibus was brief in America’s cities but very important to the expansion of the riding habit. Providence in the 1850s was still a “city of pedestrians.” The state’s population and downtown business district were just too small to sustain more than a modest fleet of omnibuses but they provided a glimpse of what was to come.

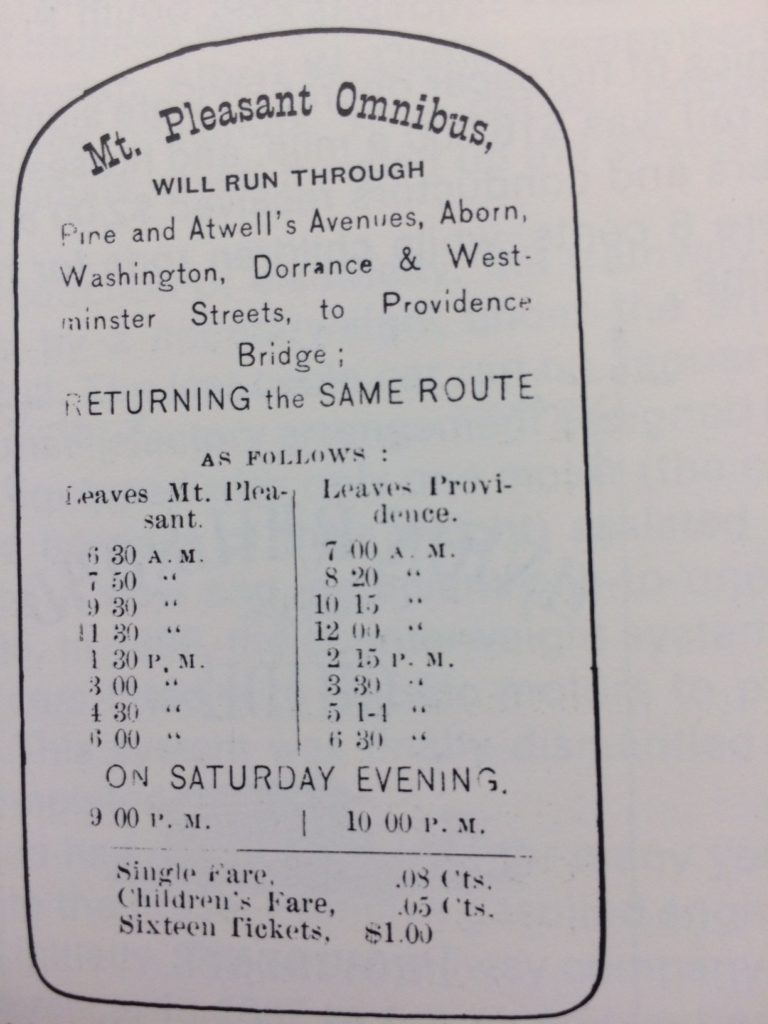

Early omnibus timetable on Mt. Pleasant route. Note the “late service on Saturday night” (Scott Molloy Collection, Robert L. Carothers Library (at URI), Special Collections and University Archives)

The antebellum decade was the heyday of the bus in the Ocean State. The most patronized line bumped along Broadway in Providence to the bustling factories and tenements of Olneyville. Lucy Howlett, a seamstress who worked in Providence between 1848 and 1852, was a typical rider. She made a notation about a bus ride in her unpublished diary on March 24, 1850: “Yesterday we had a snowstorm. The snow was falling all day, but the weather was so warm that it did not accumulate very fast, but the walking was very bad. I rode home in the Olneyville Omnibus with eighteen other passengers.” Earlier that month she mentioned a similar ride when it rained. Most workers and especially mill operatives could not afford daily ten cent fares and walked whenever possible, saving a fare for bad weather or a Sunday outing. By the Civil War the Olneyville line operated every ten minutes.

Other routes ran less frequently on half hour and hourly schedules. The line to Friendship Street in Providence, for example, left every sixty minutes from 6:30 a.m. to 7:00 p.m. Similar service was provided to South Main Street, South Providence, East Providence, Elmwood, Knightsville, Smith Hill, North Main Street, Charles Street, and to the Pawtucket city line. There were incidental trips between several downtown train depots. A Providence timetable in 1853 promised that passengers could leave downtown at noon, have lunch on the East Side, and return to work by one o’clock.

The description of the East Providence omnibus was typical of the period. Passengers entered the “turtleback” through a rear door with three steps. A leather strap attached to the door extended along the top of the inside roof of the bus and was wrapped around the driver’s leg at the front of the vehicle. When a patron wished to leave, he tugged on the strap, paid the fare and the driver loosened the cord. The author of a local transit article in 1930 suggested that “As most of the drivers owned the bus which they drove it is a safe bet that they never ran by any passengers.”

One particularly pleasant omnibus line went from downtown Providence to Swan Point Cemetery, a bucolic spot located at the end of Blackstone Boulevard. A popular carriage rendezvous after the Civil War, the cemetery was more of a public park than a place of eternal rest. Swan Point accommodated thousands of guests on summer Sundays. When the Union (Horse) Railroad initiated a route to nearby Butler Avenue in 1876, about a mile and a half from the cemetery, the omnibus simply shortened the line and carried passengers from the horsecar terminus to Swan Point. Displaced omnibuses from the former Mount Pleasant line were transferred to the East Side for this this popular service. The horsecar company purchased the profitable franchise the following year and outfitted its own larger bus to handle the crowds. The Butler Avenue line was electrified and extended to the gates of Swan Point in 1900.

Riding conditions were primitive, of course, on all lines. There was no heat so a layer of straw served as insulation. Patrons claimed the straw was liberally spread, not to provide rudimentary comfort, but to hide any change that a customer might drop. Drivers retrieved coins at the end of the line. In 1864 the Manufacturers and Farmer’s Journal observed another form of larceny: “The man who smokes in the Omnibus may be mean and disgusting, but he isn’t so dangerous a fellow passenger as the man who rides in the omnibus for the purpose of appropriating articles that may be dropped or left in the vehicle.” In later years, when the status of bus travel had deteriorated, riders on the Lonsdale line were still complaining about smoking. The Providence Morning Star frowned on such transit behavior and condemned “the nuisance of nasty pipe smoke, particularly in the presence of ladies, and not especially agreeable to any inhaler of God’s pure air.”

The omnibus in the background once had a monopoly on service to Blackstone Boulevard on Providence’s East Side. Horsecars, using rail lines, began service in 1876. The two forms of transportation clashed in a race in which the railed, upstart horsecar was destined to win. (Courtesy of Bob Bennet)

Surprisingly, the omnibus did not disappear with the coming of the horsecar, which, since horse-drawn car traveled on steel or iron rails, could carry more weight. Ebenezer Allen, the proprietor of the South Main Street omnibus, apparently attempted to amalgamate the different bus lines. The accompanying timetable advertised “Allen’s Line of Omnibuses” to the following streets: Hope, South and North Main, Charles, Cranston, Broad and High (present day Westminster Street). The dream of a unified system of mass transit in and around Providence would come later, however. Most bus franchises were purchased by the horsecar company in the 1860s. Although the “animal railroad,” as the horsecar was sometimes referred to marginalized the omnibus, the surviving bus lines served a purpose. Horsecar proprietors kept a close eye on bus patronage, especially in emerging neighborhoods, as an indicator of profitable new routes for rail transit.

This omnibus from the University of Rhode Island carried students and professors from the Kingston Railroad station to the campus probably from the inception of the school in the 1890s and well into the 1920s when the vehicle had disappeared from places years earlier. (Scott Molloy Collection, Robert L. Carothers Library (at URI), Special Collections and University Archives)

By 1882 seven omnibus lines survived in Providence although some were relegated to picking up school children. The introduction of electric streetcars to the state in 1892 began a decade of trolley extension into every major community. The electric railway even replaced passenger traffic on some established railroads. The trolleys and outgoing horsecars managed to create a few new omnibus lines even at this late date. When the Union Railroad extended Elmwood Avenue horsecars to Auburn in Cranston in 1878 an independent omnibus ran service between that community and the state prison at Howard twice a day. That line was electrified in 1898. The Rhode Island Company, the successor to the Union Railroad in 1902, operated the state’s last omnibus line in 1904 when it used a primitive wagon-bus on a crosstown route between Knightsville and Edgewood in Cranston. This Park Avenue line was electrified in 1908, finally ending the six decade journey of the omnibus.

The anonymous author of an article in All Aboard, an employee publication printed by the local United Electric Railways Company in the 1930s, wryly noted that “Those old omnibuses crawling along through dust and mud were doubtless expected to fill the bill, forevermore, but like the stagecoach they had to yield to the march of progress.”

[Banner Image: This omnibus from the University of Rhode Island carried students and professors from the Kingston Railroad station to the campus probably from the inception of the school in the 1890s and well into the 1920s when the vehicle had disappeared from places years earlier. (Scott Molloy Collection, Robert L. Carothers Library (at URI), Special Collections and University Archives)]