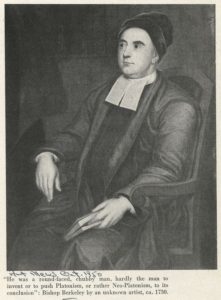

One of the most exciting European visitors to colonial America was the Very Reverend Dr. George Berkeley (1685-1753), who spent most of three years in Rhode Island. The rest of the world knows Berkeley (pronounced Barkly) as a leading immaterialist philosopher, whose motto was “Esse est percipi,” to be is to be perceived. He is the one who posed the question, if a tree falls in the forest and there was no one there to hear it, did it make a noise? Philosophy eventually dealt harshly with that view. As Ronald Knox wrote about Berkeley in the early twentieth century:

There once was a man who said, “God

Must find it exceedingly odd

To think that a tree should continue to be

When there’s no one about in the Quad.”

“Dear Sir: Your astonishment’s odd.

I am always about in the Quad.

So that’s why the tree will continue to be,

Since observed by, Yours faithfully, God.”

Historian Walter Isaacson, in his recent biography of Benjamin Franklin, called John Locke and George Berkeley the greatest philosophers of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. Isaacson admitted that the great Franklin did not rise to that level, at least as a philosopher.

Berkeley was born in Ireland. He attended Trinity College, Dublin, and began to teach there. The College Library has subsequently been named the Berkeley Library. He was good friends with leading writers of his day, including Swift, Addison, Steele, Pope, and Defoe, as well as Irish Archbishop Arthur Price, who was also an official at Trinity College. (A member of the famous Guinness brewing family, then in his 90s, told me that just before Price died, he gathered together his servants, all members of the Guinness family, and gave them his family’s secret recipe for stout and money to build a brewery, which started the family business). Berkeley was soon ordained a priest in the Church of Ireland (Anglican) and later promoted to Dean of the Diocese of Derry in the north (he was sometimes thereafter called Dean Berkeley).

As early as 1720, Berkeley began dreaming up a scheme to educate American Indians. He wanted to found a college for them, but almost immediately he realized that such a plan had problems. First of all, some typical Indian chiefs were already saying, “Why should I send my young men to study your worthless stuff, unless you send an equal number of your young men to study useful stuff with my tribe, such as hunting, tracking, and fishing?” Second, when America’s existing colleges did attempt to educate Indians, many of those Indians, understandably, when the Latin and Greek appeared too difficult, would simply knot their sheets together, sneak out a back window, and melt away into forest tribes, never to be seen at the college again. The existing colleges in Berkeley’s day were: Harvard (Massachusetts Hall still stands from his day); the College of William & Mary at Williamsburg, Virginia, where the great physicist/chemist Robert Boyle had left the Brafferton Endowment specifically to educate Indians (Brafferton Hall and the original “Wren” Building still stand from Berkeley’s day); and Yale College at New Haven, Connecticut (it was the third college of English-speaking America, but no buildings from Berkeley’s day remain).

Berkeley conceived a radical idea: place his new college in Bermuda, where there were no Indian tribes for the students to escape to, so they would have to continue through until graduation. Berkeley made an official proposal to German-speaking George I and Parliament that they should back the college financially. The king liked the idea and promised 1,000 pounds per year from his revenues from the Caribbean island of St. Kitts, and Parliament promised to commit 20,000 pounds from general revenues. George I issued a formal charter for Saint Paul’s College, Bermuda, in 1725. The official seal of the college showed a lighthouse, presumably lighting the way for the Indians as well as for any English colonists who might want to attend.

Officials in London soon began to grumble. General James Oglethorpe, they said, wanted to found the new colony of Georgia (named after King George, of course), and there would not be enough money for both projects. Then, in 1727, the king died, to be replaced by his German-speaking son, George II. George II typically automatically opposed anything that his father had supported, but he urged Berkeley to go to America to wait for the money. As a result, Berkeley assembled some of his college faculty and moved to Newport, Rhode Island (with a brief stop at Williamsburg in order to observe how the Indian education system worked at William & Mary).

Newport, Berkeley said, had the reputation for the most moderate climate in America, and he arrived there January 23, 1729. Berkeley brought with him two Fine Arts professors, Richard Dalton and the Scotsman John Smibert, and two Music professors, John James and Carl Theodore Pachelbel, son of the famous composer Johann Pachelbel (who wrote the celebrated Pachelbel’s Canon in D). James turned out to be an alcoholic, so he was soon sent packing back to London, but not before he had written some organ music and Smibert had created a giant painting of Berkeley and his group, including James. Since he was likely to be staying in Newport for a while, Berkeley bought a farm in Middletown, and he had Dalton take the little farmhouse and enlarge it with an elegant design into North America’s first Palladian-style house, which he named Whitehall. Middletown, incidentally, was set apart from Newport in 1731, while the Rhode Island General Assembly considered a petition by its freeholders to create a new town, but it was not incorporated until 1743.

Berkeley set Dalton the task of designing the layout of the campus for the proposed Saint Paul’s College in Bermuda. He also designed the college chapel (never built) to look like a first-century Roman temple. Berkeley and his entourage raised the whole intellectual and cultural tone of life in the Newport area. They founded an informal club to discuss philosophy and many other high-brow topics, calling it the Philosophical Society, which eventually in 1947 reconstituted itself as the Redwood Library & Athenaeum. Berkeley made friends with nearly everyone of importance in the Newport area, regardless of their religious affiliation.

Berkeley was pleased to meet an Anglican clergyman loosely associated with Yale College, the Reverend Dr. Samuel Johnson (NOT the London Dr. Samuel Johnson who wrote the famous Dictionary), and the two men spent endless hours discussing matters of mutual interest. In 1749, perhaps recalling the inspiration given him by Berkeley, Johnson began considering a college in New York City. In 1754, just after Berkeley’s death, he secured a royal charter from George II to found King’s College in New York City, since renamed Columbia University. Benjamin Franklin and his friends in Philadelphia, who may also have been strongly influenced by Berkeley, took several years from 1740 to 1755 to found The College at Philadelphia (now known as the University of Pennsylvania).

Berkeley normally worshipped at beautiful Trinity Church, Newport, which had been built in 1723 to designs by former Virginia Governor Francis Nicholson. Trinity was over one hour’s walk from Whitehall.

Berkeley was a prolific writer, and while in the Newport area he spent many hours meditating on top of Paradise Rock at what is now Second Beach, looking out to sea. (In the late 1880s, it was also called The Bishop’s Seat, after Berkeley). There he wrote the long poem Alciphron, whose last verse is as follows:

Westward the course of empire takes its way, the first four acts already past;

A fifth shall close the drama of the day; time’s noblest offspring is the last.

The United States westward expansion movement in the nineteenth century took that verse as its mantra.

Berkeley continued writing letters to London in order to find out about the long-awaited money. George II, although he had nothing personal against Berkeley, had no intention of sending the money that his father had promised. Prime Minister Robert Walpole wrote to Berkeley in 1731, “If the president of the college is enquiring about the money, I shall have to tell him that it should arrive some day, but if my old friend Berkeley is enquiring I shall have to be candid and tell him that the money will never appear.” Meanwhile, Oglethorpe received the money he needed to found the colony of Georgia.

Berkeley returned to Britain in 1731-2. The books that he had carefully collected for Saint Paul’s College Library he distributed between Harvard and Yale. The Yale component approximately doubled the size of that college’s library, but the Harvard component was destroyed in 1764 when Harvard Hall (then being used as a temporary home of the Massachusetts legislature) burned to the ground. As a consolation, Berkeley was consecrated Bishop of Cloyne, a small diocese in southern Ireland near Cork that has subsequently been absorbed into a larger diocese. The tiny gothic church of Saint Colman that served as its cathedral still stands. Berkeley retired in 1752 and moved to Oxford, in part to be near his son who was a student there. He also enjoyed matching his wits to the professors there, but he died after only a few months and is buried at Christ Church, Oxford.

Berkeley is highly regarded today in some academic circles. The Berkeley Divinity School at Yale is named after him, and the university town of Berkeley, California, originally called Ocean View, was renamed after the Irish philosopher. Philosophers and historians assembled in Newport in 1975 to found the International Berkeley Society, which has meetings and members all over the world.

Berkeley donated Whitehall to Yale, with the stipulation that money derived from renting it out should go to forward Indian education. One of the first recipients of the Whitehall scholarship went on to found Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, which became renowned for educating North American Indians. Remembering fondly his time in Newport, Berkeley approached the composer Handel and asked him to supervise organ-builder Richard Bridge in making an organ to send to Trinity Church, Newport; the organ case is still in place, and contains a tonal copy of nearly all of Berkeley’s organ.

Modern view of Whitehall Museum House in Middletown, home of the International Berkeley Society (Providence Public Library Digital Collections)

Richard Dalton returned to London, where he was one of the founders of the prestigious Royal Academy of Arts in 1768. John Smibert moved to Boston, where he became New England’s leading painter until his death in 1751. He also supervised construction of Peter Harrison’s Faneuil Hall in Boston.

Carl Theodore Pachelbel remained in America, where he served as organist at King’s Chapel, Boston, then at Berkeley’s organ at Trinity Church, Newport; then at Trinity Church, New York; then at Christ Church, Philadelphia; and finally at Saint Philip’s Church, Charleston, where a concert series and a singing school that he founded developed into the Saint Cecilia Society in 1766, America’s oldest musical organization. Pachelbel, who composed a few instrumental and choral pieces, died in 1750.

Oglethorpe’s founding of Georgia in 1732 even contained echoes of Berkeley’s plans. Among the first settlers were the Reverend George Whitefield, famous for his booming voice, and the Reverend John Wesley, who later founded the Methodist Church. Both of them were profoundly influenced by a group of other settlers in Savannah, a congregation of German-speaking Moravians. The Moravians were the descendants of the Czech group who had established the world’s first Protestant church, a century before Martin Luther. Together, they founded in 1738 the Bethesda orphanage and set in motion Whitefield College, intended for both English and Indian students, which however was abandoned in 1776 before any buildings had been built for it. Oglethorpe had impressed the first settlers with his proclamation that Georgia would never permit slavery, other than seven-year punishment of both white and black petty criminals, but in 1740 it was reluctantly determined that Georgia could not survive and prosper without regular slavery.

At that point, the Moravians all departed and moved to Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, where they founded Bethlehem College in 1742 to educate both European Americans and Indians, including women – the first college in the British world to educate women. Bethlehem itself was established as a voluntary communist society in which everyone in the town worked for a wage paid by the Moravian Church, and the church used the profit to send missionaries to educate Indians in western Pennsylvania and Ohio. This was so successful that the Moravians founded Salem, North Carolina in 1767 (since renamed Winston-Salem) in order to repeat the procedure for southern Indians. So, the Moravians, who likely never heard of Berkeley, actually did much of what Berkeley had been unable to do, and then some. He would have been proud, had he known about it. As for Bermuda with its population of only 65,000, it still has no college, so all its would-be students are required to go to Europe or North America for their higher education.

The standard reference for Berkeley’s sojourn in America is Edwin S. Gaustad, George Berkeley in America, Yale University Press, 1979, and still in print.

Readers can also view a high-level lecture on Berkeley’s philosophy by a Wheaton College professor at the following website: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6LM8M6lqc8M

Berkeley’s historic home in Middletown, which is open to visitors, as is it’s marvelous gardens, is held by The National Society of the Colonial Dames of America in the State of Rhode Island and operated by the International Berkeley Society. Its website also contains some lectures on Berkeley’s philosophy by visiting scholars (at www.whitehallmuseumhouse.org).