This article focuses on the “top secret” World War II German prisoner of war camps at Forts Getty and Wetherill in Jamestown, Rhode Island. A companion article, “The Top Secret World War II Prisoner-of-War Camp at Fort Kearney in Narragansett,” should be read first to obtain a proper background for this article.

Among the several missions at the “Idea Factory” in Fort Kearney (see the prior article) was to establish an “experimental school” for a select number of anti-Nazi German POWs to undergo reeducation. Successful graduates were to serve as administrators, assisting U.S. military government personnel in post-war Germany. After the idea for such a school was developed at the Factory in February of 1945, support for it was later received from U.S. Army officers still battling in Europe, including General Dwight Eisenhower himself. On March 19, 1945, the Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army approved the training of anti-Nazi POWs.

The talented commander of the Special Projects Division, Lieutenant Colonel Edward Davison, gathered a number of brilliant professors and other intellectuals to serve as teachers and lecturers. They included Dr. Howard Mumford Jones, a Harvard University professor and dean, and one of the founders of American Civilization studies; Dr. Henry Ehrmann, a Jewish refugee who had fled Germany to escape Hitler, been imprisoned in France, and escaped from there to America; Lieutenant Colonel T. V. Smith, a former Congressman from Illinois and professor at the University of Chicago; and Major Burnham Dell, head of the military government department and a former Princeton University professor. Some of the instructors, like Jones and Ehrmann, were hired as civilian consultants, while others, like Smith and Dell, had become officers in the U.S. Army. POWs at Fort Kearney were also called upon to lead small group discussions.

The first 61 students, of the eventual 101POWs who would constitute the first class, arrived at Fort Kearney on April 28 and 29, 1945, even before the surrender of Germany the next month. (One of them was returned to his former camp, as he was working as an informer with G-2, U.S. military intelligence.) The select POWs entered into a curriculum focused on English as a second language, military government, and democracy. These classes were supplemented by informal discussion groups, visiting lecturers, quizzes and exams. The final stage included an interview to determine how much the POWs had learned and how useful they could be to postwar Germany and the American military occupation government to be established there. Once the POWs successfully completed the sixty-day program they became eligible for early and direct repatriation to Germany. The program was found to be a success, with seventy-three POWs “graduating” at dignified ceremonies on June 29 and July 6 and then shipped to Germany.

Fort Getty staff and faculty, about November 1945. Lieutenant Colonel Alpheus W. Smith is front and center, with Brigadier General B. M. Bryam, Assistant Provost Marshal, to his left (Jamestown Historical Society)

For the next phase of the reeducation effort, the War Department agreed to establish the “United States Army School Center” at two Jamestown locations: Fort Getty, which would house the Administration School for training future government administrators in postwar Germany (approved May 19, 1945), and Fort Wetherill, which would house the Police School for training future policemen to work in occupied Germany (approved June 2, 1945). The two camps were located on Conanicut Island, which encompasses the entire town of Jamestown. Fort Wetherill had a gorgeous position on the southeastern part of the island with a view overlooking the entrance to the East Passage of Narragansett Bay and in the distance Newport Harbor, while Fort Getty on the island’s west side was directly opposite Fort Kearney across the bay’s West Passage. The two camps would allow more POWs to be reeducated than at cramped Fort Kearney.

Lieutenant Colonel Alpheus W. Smith, a former English professor at Northwestern University and a World War I veteran, was selected to head the two schools, with the title of Chief, Prisoner of War Schools Branch, Provost Marshal General’s Office. Smith, most of his staff officers, and most faculty members, who supervised the schools or taught at them, resided at Fort Kearney or on the mainland. The total staff for the schools consisted of 58 officers, 115 enlisted men, and 12 civilian consultants.

The Conanicut Island locations of Forts Getty and Wetherill were ideal places for POW facilities, since they were on a small island with access to the mainland at the time only by a bridge across the West Passage and by ferry on the island’s east side to Newport.

Fort Wetherill had been the site of a battery in the Revolutionary War to defend the entrance to Newport Harbor. In the late 1800s it was replaced by one of the so-called Endicott fortifications armed with large breech-loading coastal artillery pieces designed to combat ironclad, steam-powered warships. The new facility was named in honor of Captain Alexander Wetherill, a Jamestown native killed in the Spanish-American War at the Battle of San Juan Hill. After World War I, the fort was placed in caretaker status but was reactivated in 1940 as part of an extensive buildup of Rhode Island’s coastal defenses.

Fort Getty, built around the same time as Fort Wetherill, was named in honor of Colonel George W. Getty, who served in the Mexican War and the American Civil War. Along with Fort Kearney, it also served as one of two anchor points for an antisubmarine net stretched across the West Passage. POWs and faculty could be easily moved by small boats across the narrow West Passage between the two forts, avoiding the longer trip over the Jamestown Bridge and the curious stares of local civilians.

Early in World War II, both forts had hosted coastal artillery units intended to defend Rhode Island from attacks by German submarines or other naval forces, but, as that threat had receded, the forts were largely abandoned and the heavy artillery was removed, but the wooden barracks, mess halls, and other buildings, many built in the early 1940s, remained. In 1945, they were declared available for use by the Special Projects Division.

A rigorous selection process was undertaken to choose the POWs who would serve as the schools’ first students. German POWs wanted to enter the programs because they had learned that, despite the end of the war in Europe, they would be shipped to England, France, and other allied European countries to perform one or two years of forced labor. By being selected to attend the Fort Getty or Fort Wetherill schools, the POWs could return to Germany and their families faster.

Candidates had to be anti-Nazi, trustworthy, loyal, industrious, in good health, not have a rank over captain, not be under age twenty-five, and not display militaristic tendencies. Many, but not all, had graduated from college. The Special Projects Division whittled down a list of 17,883 POWs to just 816 suitable candidates for Fort Getty and 2,895 for Fort Wetherill. These candidates were further interviewed, tested and evaluated, many at Fort Devens in Massachusetts.

A number of the candidates hailed from the 999th Light Afrika Division, which included many concentration camp prisoners who had been forced to join the outfit. While most of these men were petty criminals, some were political prisoners who had courageously resisted Nazism. Most of the division surrendered in North Africa before it engaged in fighting, thus providing another benefit for the Special Project Division—American parents could not say their children were killed by its soldiers.

Captain Robert L. Kunzig, the commander of Fort Kearney, recalled that many criminals from the 999th tried to fake being professors, writers or political prisoners. “Everyone would say he was a professor or a political leader when he might be a murderer,” Kunzig remembered. But often it was fellow prisoners who exposed the fakers.

POWs arriving at Forts Getty and Wetherill underwent further vetting, which sometimes established that a number of them did not meet the stated criteria. On August 6, 1945, sixty-one POWs who had been sent to Fort Getty but had then been rejected, some for being Nazis, were brought by boat over to Fort Kearney. An American officer at the scene wrote a few days later that these POWs “were very downcast. We were all somewhat fearful that there might be some attempted escapes on the part of the prisoners” who had hoped to join the school as way to get back to Germany quickly. An extra guard was assigned to these POWs; one of the Kearney POWs spoke to the newly-arrived prisoners and helped to defuse the situation.

The POWs who were selected to enter the schools at Forts Getty and Wetherill, as at Fort Kearney, agreed to renounce their military ranks so that all of the POWs could relate to each other as equals. They promised not to try to escape through the barbed wire. And they pledged that when they returned to Germany as civilians they would aid the American occupation forces to help govern the American zone in Germany.

POWs selected to be students were brought to Fort Getty secretly at night by truck. Wolf Dieter Zander, then a twenty-nine-year-old POW who had served as a junior officer in the 10th Panzer Division in North Africa, recalled the morning he was brought to Fort Getty. “The morning fog had prevented us from recognizing where we were, though we smelt the salt water of the sea. At noontime, after having several roll calls . . . the sun pierced through the fog and lifted the veil around us. We found ourselves on a small island, a rock in the sea. . . . We liked it from the first day, though [the sea] separated us from home.”

The POWs were required to wear standard U.S. Army prisoner-of-war uniforms, with the large letters “PW” stamped on each item. But other than that, Fort Getty was an unusual POW camp. One of the instructors, James Ruchti recalled, “instead of fences and guards . . . we had a three-strand barbed wire fence which we had to put up for token reasons.” In addition, he remembered that each of the guards had been “a former prisoner of the Germans themselves” and “therefore were very understanding of what it meant to be a prisoner.”

The camp permitted POWs to send and receive mail, but any mail went through censors. In addition, family visitors were allowed. By October 30, 1945, about six visitors a week were arriving at the gates of Forts Getty and Wetherill.

One newspaper report described a typical barrack at Getty. Ninety POWs occupied a room usually allotted to sixty-five American soldiers. Their bunks were stained, wood-frame double-deckers, and when seen by an inspection party “were clean and orderly—characteristic of the entire camp.” Classes were held mainly in the old hospital, which was converted into fifty-six small classrooms. Two libraries were created at Getty, one for study and the other with an impressive book collection, most of which had been loaned by American universities. Two copies of Conrad Heiden’s vitriolic biography of Adolph Hitler were well thumbed.

Fort Getty’s first classes began on July 19, 1945, with the sixty-day curriculum again focusing on the English language, German history, American history, and military government. Fort Wetherill emphasized the last as part of its core mission to train policemen and thus spent less time on the other subjects. The primary idea that the instructors sought to convey to the prisoners was that democracy was not only a form of government, but was a way of life that could serve as a guide for future behavior.

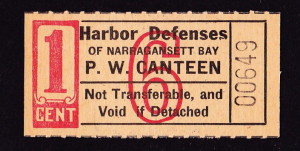

A chit for POWs to spend at the camp canteen store at either Fort Getty or Fort Kearney, February-March 1946 (RICurrency.com)

The enthusiastic spirit of Fort Kearney carried over to Fort Getty. Dr. Walter Hallstein, who would become the most prominent of the Getty graduates, later wrote, “The atmosphere in the stalag between the inmates, the teachers and the staff was terrific . . . . The selection of the faculty, and the methods they used to present the material made it very successful.”

Lieutenant Colonel Alpheus Smith explained that his team of instructors operated on “faith and trust” that the selected POWs would be interested in rebuilding Germany on democratic principles. Wolf Zander recalled how he and his fellow classmates came to drop their suspicions and be open to learning: “the G. I. guard at the compound gate was . . . full of friendliness and willing to meet the other fellow half way. Then our instructors’ missionary enthusiasm—an American trait which fascinates the tired, fatalistic European—would not fail to have its effect. Or it may have been our hosts’ complete lack of prejudice. Or was it the landscape, the air, the rock in the sea? Indeed I do not know just what the reasons were. Nor do my friends.”

The most beloved professor was American history teacher T. V. Smith, a University of Chicago professor, author of best-selling books on American life, host of a popular radio show, and a former Congressman from Illinois. Then a lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army, Smith emphasized the successful resolution of conflicts in American history, in contrast to the approach that had been followed in Germany of picking a leader who made everyone follow his policies. Yet he criticized the Civil War as a failure of U.S. democracy. The students were not used to their own country being criticized and thus, as one POW recalled, “We were amazed at the frankness with which all the topics were discussed, as e.g., the Civil War was mentioned as a black point in American history.”

Smith wanted his students to let their guards down to facilitate discussions and learning. At the start of one course, he saw that his POW students stood at attention when he entered the classroom, clicked their heels when they got up to speak, and bowed from the waist when they finished. The next day, when the students entered the classroom, they gaped in wonder at their professor with his feet on his desk.

Smith provided a sample of his lectures to a small audience at a Y.M.C.A. supper in Newport on September 28, 1945. He said that the three mighty truths that made the United States great were separation of church and state; the doctrine of judicial supremacy wherein final authority rested with the Supreme Court, “which has no money, no army and no navy, and no power beyond its own decisions;” and the absolute authority of civil government over the military. “It is a rare and thrilling experience to teach about liberty behind barbed wire,” remarked the former Congressman.

Dr. Ehrmann, teaching German history, found that many of the POWs treated the rise of Nazis as an historical accident and needed to be taught about the German and Prussian militaristic traditions. At the same time, he emphasized democratic trends in German history and attacked German passivity. Student Zander was deeply impressed that Ehrmann, although a Jewish refugee who had fled from Germany, treated him and other German POWs with the kindness and dignity that the professor had never been afforded in Germany. Another student remembered the school’s emphasis that the prisoners had to learn to think for themselves and not passively accept dogma. “The prisoners were found to be to an amazing degree ignorant of the political, legislative, and financial structures of their own country,” one U.S. observer noted.

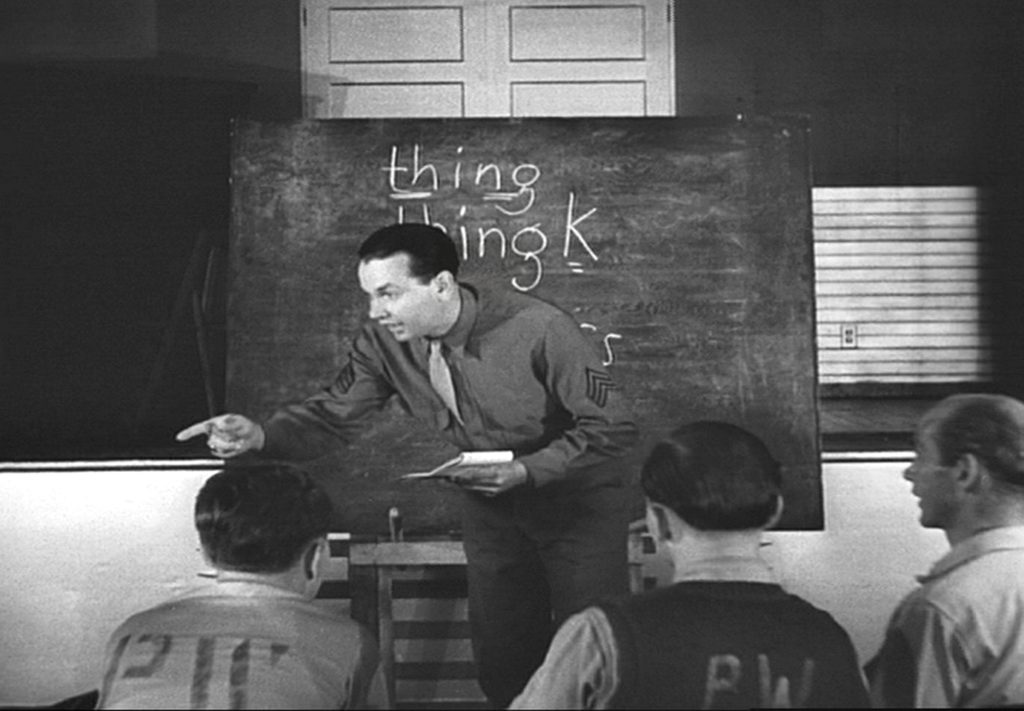

Former Brown University professor Major Henry Lee Smith led the effort to instruct POWs in the English language, since that was needed for the graduates to cooperate with the American military government in Germany. Major Smith taught his own unique—and successful—fast-paced method for teaching colloquial English. (There were so many officers named Smith at Getty that, in a breach of army rules, they started to be called by their first names.)

While Fort Wetherill relied on the Getty instructors, it also used a staff of police officers and commanders from New York City, Cincinnati, and several other cities as teachers of police methods. Major Kenneth K. Kolster, the school’s commander, stated that the school emphasized decentralized police control of Germany on a local basis, in contrast to the centralized control of the Gestapo.

American instructors learned German traditions as well. “At the end of my first lecture,” said a lieutenant, “the class began to stamp on the floor like a herd of buffalo. I was so scared I almost called the MPs. Then I found that stamping on the floor is the German student’s way of applauding.” Students would show their displeasure by scraping their feet back and forth on the floor.

A favorite topic among the students at Forts Getty and Wetherill was the poor treatment of American blacks. While most instructors had difficulty dealing with the subject, T. V. Smith, a native Southerner, found it easier to handle than his Northern colleagues. He conceded his country’s substantial shortcomings (a credit to him as a Southerner in 1946) but asked his students to consider the progress blacks had made and requested suggestions from the students on how to improve their treatment. Smith later wrote that camp instructors were directed “to tell the truth” and “to be candid under questioning” by the POWs. Similarly, in greeting new enrollees with a welcoming speech, Getty and Wetherill commandant Lieutenant Colonel Alpheus Smith admitted, to the surprise of his eager listeners, that “American democracy wasn’t perfect.”

T.V. Smith once happened upon this wonderful scene at Fort Getty: “I stood there, an autumn evening at sunset, behind the barbed wire of a German prisoner-of-war compound, looking at a dozen P.O.W’s as they themselves in silence watched the sun go down across Narragansett Bay. Not a word was spoken . . . . The dozen German prisoners stood in single file upon Fort Getty’s high bank of the Bay with their hands behind their backs, stood so long and so eloquently that at last I walked away, without my reverence at the scene having been so much as remarked by them.” Soon the men went back to studying. “They even study with a vengeance,” Smith wrote.

The screening for the first class at Fort Wetherill was poorly done. A total of 258 POWs arrived at the camp by tarp-covered trucks at 1:30 a.m. on August 10, 1945, for the initial class. Due to transfers from Fort Getty, this total was increased to 294. But as a result of further screening, 139 were rejected before the first class even began. These men failed to meet the stated criteria, with a number of them being described as “politically unreliable,” with explanations such as “strong Nazi leanings,” “Hitler Youth,” and “probably Gestapo.” Eventually, 145 POWs from the initial class graduated on October 13, 1945.

TV Smith addresses POWs graduating in a ceremony at Fort Getty (Edward Davidson Papers, Yale University Library)

At Fort Wetherill, since the students were to become policemen, it was decided that they should be more carefully screened than the candidates for Fort Getty had been. Upon their arrival at Wetherill, each took a polygraph test, supervised by police officials from major cities around the country. Some who had Nazi sympathies, communist leanings, or just wanted to graduate to get home quickly, failed the lie detector test and were removed from Fort Wetherill.

At any one time, there were typically about 200 students at Fort Getty and 150 at Fort Wetherill taking classes. Other POWs were usually at the camps, getting screened and waiting to start their classes.

There was not much interaction between the POWs at Forts Getty and Wetherill and Jamestown residents, but there was some. POWs were not allowed to stroll around town unescorted. However, they could use the beach near the school, and a few Jamestown residents remember seeing some of them on work details. As set forth in the August 5, 2010, edition of The Jamestown Press, Alcina (Lopes) Blair, a lifelong resident of Jamestown, recalled that as a young teenager, she saw “prisoners go by in trucks.” She surmised that they were on their way to the garbage dump as they traveled along Southwest Avenue. Another longtime Jamestown resident, Delores Christman, when she was fifteen years old, remembered the POW trucks going up and down Southwest Avenue to and from Fort Getty. “They would wave at us and we would wave at them,” she said.

One night, Blair further recalled, two prisoners, who had gotten lost, appeared on the front porch of her family’s resident on Windsor Street. “My mother and father were concerned and called the chief of police who came and got them,” she said. “They were not escaping. They were lost.”

No POW at Fort Wetherill ever escaped and only one POW at Fort Getty escaped. The escapee was grey-eyed and dark-haired Gerhard Hetzfuss, aged thirty-two, a former private in the 999th Division. The FBI, state police, and police in various southern New England communities joined in trying to capture Hetzfuss, who was described as speaking good English with a slight accent. It was also disclosed that the prisoner had been due to be returned to Germany in a few days prior to his escape in late January 1946. It turned out that the POW had run off with his American girlfriend; the two were captured in a hotel room in New York City. Rather than return to a devastated Germany with an uncertain future, Hetzfuss wanted to start a new life in America. It is not known if his female friend worked at Fort Getty or helped him to escape, or both.

The authors were told an interesting story by the daughter of a woman who lived near Wakefield during the war. She and some of her college-aged girlfriends were taken by a covered truck at night to a dance held for POW camp guards. She thought the location was at Fort Getty, but could not be sure due to the secrecy imposed on their trip. She temporarily dated one of the camp guards, who was Jewish. It was not unknown in the U.S. for some camp guards to be Jewish, despite the Holocaust.

In September 1946, an unnamed German army captain who had graduated from Fort Getty gave a detailed interview to an intelligence officer in the U.S. zone in Germany. This man had been captured in North Africa on May 12, 1943, and eventually ended up at a POW camp at Mexia, Texas. Nazi POWs at the camp started a “reign of terror and tried to squelch any opposition,” but the captain and other anti-Nazis opposed them, with the result that there were “continuous quarrels and fights.” After this camp was disbanded, the captain was transferred to Camp Dermott in Arkansas. There he was successfully screened for acceptance to the military government school at Fort Getty and he gladly volunteered to enroll there. “After the flatlands of Arkansas, Rhode Island was pleasant and lovely and reminded us a bit of home. We went swimming every day, the food and the accommodations were very good. We saw and ate things which we had not in years. We began to lose the feeling of being prisoners of war altogether . . . . We chose section leaders, regardless of former rank and position. It was quite a pleasant relief to be called mister again after having been captain for so long.”

Class work at Fort Getty was demanding. The German Army captain recalled:

Aside from a seven-hour lecture schedule we had four-to-six hours each day for homework and preparation for the lectures. In the morning, we learned English for four hours and in the afternoon either history or military government. One hour of P.T. [personal time] daily gave us the necessary balance. At night we had discussions which were led sometimes by Germans and sometimes by Americans. These current events discussions were something very new to most of the younger men. We continued our talks back in our barracks and talked until late into the night. In the beginning, some of the men were not altogether tolerant but gradually they too learned to respect each other’s ideas. Very soon real friendships developed between us and our American teachers, whether they were professors, officers or enlisted men. . . . [W]e spent many hours together singing German and American songs, and discussing our personal lives and families.

The captain concluded:

I shall never forget Fort Getty. It will remain to me a source of strength at all times. In spite of all the hardship which we will find at home, in spite of the perhaps sometimes unreasonable measures of some small subordinate office, the final goal of a new democracy will always be before our eyes. That was, after all, the aim of this training school: to reinstate faith and trust in mankind, not only from the economic, political or philosophical point of view, but also from the point of view that each individual recognizes the right of existence of his fellow men.

Another POW at Fort Getty at his graduation ceremony remarked, “What sincere and deep faith in man must live in a people [Americans] who conceived a school like this and made it a reality.”

A Getty graduate, Heinz Härtle, corresponded for many years after the war with Chaplain J. Edward Elliot, who had befriended the POW Härtle at Fort Devens in Massachusetts. One letter, dated April 25, 1946, was kept by Chaplain Elliot’s daughter, Martha Hartman, who currently resides in Kingston, Rhode Island. This letter reveals the time it took for a POW arriving at Getty to begin and finish classes, return to Germany, and get a job.

Härtle had been forcibly drafted into the German army in late 1942, probably into the 999th Division. In North Africa, he found an opportunity to desert to the allies and eventually was sent as a POW to Fort Devens. After undergoing a rigorous screening process there and volunteering for the school at Fort Getty, Härtle was taken by a “comfortable bus” past Worcester, to Providence and then to Jamestown, probably around July 25, 1945. Martha Hartman, then eight years old, waved to Härtle as his bus drove past the main gate at Fort Devens. After arriving at Getty, Härtle had a few weeks at “the wonderfully situated camp” to enjoy “swimming and fishing.” In early August, he underwent further rigorous interviews, testing and other screening procedures. Finally, he was accepted into the school and started classes on September 3. After the “hard” but exhilarating sixty day course, Härtle graduated and received his Certificate of Achievement on October 20. Just nine days later, he embarked from Boston on a ship bound for Germany.

After landing in Europe, he and his group of POWs crossed into Germany on November 9 and were discharged as prisoners-of-war on November 16. It then took him more than ten weeks to receive permission to travel through the Russian zone, which he needed to reach his small apartment in bombed-out Berlin. After not hearing from his beloved wife during the time he was a POW and still wondering if she had survived the war, he received a letter from her—she was alive and the apartment was somehow unscathed. After an excruciating wait, he finally received approval to travel to Berlin, and probably in early February of 1946 reached it and reunited with his wife. He had not seen her in three years, two months and three days. Fortunately for the Härtles, they lived in the American sector in Berlin. Upon arriving Heinz Härtle “had to report to the military government” and, after doing so, he obtained a job as a court interpreter.

On May 28, 1945, less than three weeks after Germany’s unconditional surrender, the Office of the Provost Marshall General declassified the reeducation program for POWs and announced it to the press. This was likely in response to criticism from some Congressmen and members of the press for the government’s failure to take advantage of the opportunity to rehabilitate German POWs, while the Soviet Union was suspected of indoctrinating its POWs about the benefits of Communism. Although the American public was finally made aware of the attempted reeducation of POWs, the identities of Forts Getty and Wetherill as the hosts of the two schools remained confidential.

It was not until August 23, 1945, that Rhode Islanders for the first time were officially informed of the roles of the POW camps at Forts Getty and Wetherill. Lieutenant Colonel Alpheus W. Smith made the announcement at a Newport Rotary Club lunch meeting. By September, newspapers across the country carried stories about the various reeducation initiatives being conducted in Rhode Island. The Providence Journal ran lengthy articles on September 22, 23 and 24 about the three Narragansett Bay POW camps. In addition, documentarians were allowed in to film some of the classes and graduation ceremonies at Getty and Wetherill.

Many of the professors and officers at Fort Getty had liberal or leftist leanings. As many of the POWs did as well, this may have aided them in performing the marvelous work they accomplished with the POWs. But this did not stop ugly and unwarranted accusations questioning their patriotism. On August 2, 1945, a chaplain on temporary duty at Fort Getty informed an intelligence officer, “Something is very rotten at Getty.” He stated that the “civilians in uniform” were harming the entire reeducation effort and that the “leftist” leanings of Lieutenant Colonel Alpheus Smith and Major Henry Lee Smith were apparent. He further accused Lieutenant Colonel Davison’s executive officer, Major Maxwell McKnight, of pro-Communist sympathies. As explained in the prior article, in early August 1945, Professor Jones resigned after rumors cropped up in the War Department that he harbored Communist sympathies. Other than Jones, no other senior officer or professor at Getty is known to have been investigated.

From May 1945 to October 1945, five sixty-day training cycles were conducted, which produced a total of 1,166 German graduates. Each graduation ceremony was a dignified affair held at the Fort Getty theater, with Lieutenant Alpheus W. Smith, and sometimes Lieutenant Colonel Davison, addressing the graduates. One POW graduate typically gave an address as well, including Wolf Dieter Zander.

One of the last graduation ceremonies at Fort Getty, for 160 men, occurred on December 7, 1945. With foresight, the POW speaker declared, “The goodness of democracy is not yet a reality in our country. Hunger and want will not establish it tomorrow. But it will be guiding us as our aim.” After this address and ones by Lieutenant Colonels Davison and Smith, the POWs stamped their feet rhythmically for several minutes.

Pleased with the success at Fort Getty, the Office of the Provost Marshall General decided to expand the program to handle substantially larger numbers of POWs by creating another school at Fort Eustis in Virginia. Starting on January 6, 1946, some 22,000 POWs attended the rapid six-day program at Fort Eustis before being returned to Germany. After transferring to Fort Eustis, in February 1946, Lieutenant Colonel Alpheus Smith received the Legion of Merit, mainly for his work at Forts Getty and Wetherill.

While the courses at Forts Getty and Wetherill made a deep impression on a personal level on many of the POWs, the hope that they would serve as a vanguard to spread American ideals throughout German society was overly optimistic. Their numbers were simply too small, 1,166 men in a country of 65 million people. America had the best of intentions, but lacked the time to reeducate many POWs before they had to be returned to Germany. In addition, as a frustrated Dr. Jones noted, there was little follow-up by the U.S. Army in terms of job placement in Germany. (In September 1946, a U.S. Army intelligence report indicated that about sixty percent of the Fort Getty graduates were then employed by either the U.S. military government or the German civil government.)

Many of the graduates had difficulty coping in postwar Germany. It did not help that some 60,000 Germans, many elderly, died of starvation or exposure in the winter of 1946-1947. Thirty-nine year old Konrad Sperber, in June 1946, informed a newspaper reporter, “It’s sad but true that some of us don’t feel safe to go around flashing the diploma we received from the course in democracy at Fort Getty.” He added, “I know there are many Germans who point at us as traitors or ones who have to be watched.” Sperber said he could not make the villagers near Nürnberg believe “that the losing Republican candidate in the American presidential election goes up to shake the hand of the Democratic winner and puts himself at the winner’s service—instead of fleeing into exile or being locked up in a concentration camp.” The former POW concluded that while U.S.-style democracy was workable in Germany, it would be a long haul at best.

The American occupation of Germany created resentments among the German people, with some wondering if the Americans really wanted to institute democracy. “The whole picture is the peculiar one of a democracy running a dictatorship to teach people about democracy,” wrote Professor William Moulton of Cornell University in frustration after returning from Germany in 1947. While Moulton, who had taught English language classes at Forts Kearney and Getty, reported that many Getty graduates did get work with American occupation and German civilian authorities, others were stymied by red tape and gave up in frustration. Some Getty graduates found themselves defending the American effort against criticism of their friends, explaining that the occupation authority was just a stopgap measure until the Allied powers could foster a real democracy.

In a 1948 survey of seventy-eight Getty graduates, most of the men complained that “Nazi and militarist elements are met everywhere,” and nearly half of them claimed that “widespread corruption, red tape, and the low level of both morals and morale in all aspects of public and family life” formed their first and most shocking impressions of their homeland. Almost half of them were thinking how they could leave Germany, with the United States the preferred destination. Many of them did emigrate to the U.S., including Wolf Dieter Zander, who became a successful businessman in New York City.

Still, many graduates became leaders in postwar Germany. Dr. Walter Hallstein, the most prominent of the Getty graduates, was elected president of the University of Frankfurt in 1946, where he instituted Getty-style teaching methods. In 1957, he was elected the first president of the European Economic Community and served in that important capacity for ten years. His right-hand man in the EEC, Heinz Henze, was another Getty graduate. Partly as a result of his education at Fort Getty, Hallstein developed an interest in the United States Constitution and its creation, but he was never able to push through his vision of a United States of Europe.

Of course, Germany eventually did develop as successful democracy. Perhaps the most effective argument for democracy among most German POWs was the visible affluence of America and the kindness of its people. The latter point was expressed in a letter written by former German POW Willy O. Jaeger in 1991 to a Lawrence, Kansas, newspaper. “With this letter I want to express my thanks to all the Americans who were kind to us, who didn’t treat us as enemies or Nazi criminals but as humans. In the long run this was a much better way to make us friends of the Americans, working better than any reeducation.”

By the fall of 1946, many of the buildings at Forts Getty and Wetherill had been abandoned. The October 11, 1946 edition of the Newport Mercury reported that the army was seeking to sell seventeen buildings not needed at Fort Getty, including the fire station, power plant for the hospital, five supply buildings, and sentry boxes, and that at Fort Wetherill, a number of buildings had been taken down. In 1955, the town of Jamestown purchased the land at Fort Getty to use as a town park. In June of 1971, the federal government declared Fort Wetherill to be surplus property, and in April of 1972, it transferred a fifty-one-acre portion of it to the state of Rhode Island as a public park.

When Fort Wetherill was turned over to the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management for use as a state park, the Army Corps of Engineers installed fencing around the huge wartime concrete fortifications. Thus it is possible today to get a sense of the powerful presence the fort must have presented in its prime. A few cement buildings and a dock also remain, but there are no other traces of the World War II facilities.

On the opposite side of the island, there are few remaining signs of Fort Getty. Concrete gun emplacements face Narragansett Bay’s West Passage and across towards Fort Kearney. The fort’s entrance gates have been refurbished and a few concrete foundations give evidence of the once busy facility. The Town of Jamestown has created a popular campground that attracts recreational vehicles. A long-standing plan to place a marker commemorating the presence of the POW camps has yet to be fulfilled, so few campground users know of the property’s unique World War II history.

For Further Reading:

Please consult the “For Further Reading” discussion to the prior article on Fort Kearney, as that will not be repeated here but contains the sources on which most of this article was based. Other sources for this article include Geoff Campbell, “POW Camps Little-Known Part of Island Legacy,” Jamestown Press, August 5, 2010; Lynn Ermann, “Leaning Freedom in Captivity,” Washington Post (Magazine), January 18, 2004; and an interview transcript of James R. Ruchti, an instructor at Fort Getty, done on January 13, 1997, which is available at The Franklin D. Schurz Library, Indiana University (South Bend) and online at the library’s webpage. For information about Fort Getty’s living conditions, see the October 30, 1945 edition of the Minuteman, a U.S. armed forces periodical. For the escaped prisoner, the local lecture by Getty and Wetherill instructor T. V. Smith, and the sale of abandoned buildings, see Newport Mercury, September 28, 1945; February 1, 1946; February 15, 1946; and October 11, 1946. For interviews of Getty graduates in Germany, see the Associated Press reports in The Amarillo Daily News (Amarillo, Texas), June 21, 1946, and Fitchburg Sentinel (Fitchburg, MA), April 29, 1948. For the sunset scene, see T.V. Smith, “Behind the Barbed Wire,” The Saturday Review of Literature (May 4, 1946), pp. 5-7. The authors thank Martha Hartman for providing the April 25, 1946 letter from Heinz Härtle, and her brother, Sam Elliot, for typing the letter. The Henry W. Ehrman Papers are at the State University of New York at Albany.

Using this link, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xoOu0w8ampo (or go to YouTube and search Fort Getty), the reader can view a ten minute War Department videotape of German POWs at Fort Getty taken by the War Department on December 14, 1945, close to the end of the school’s existence. Lacking any narration, the two most interesting scenes are the first one, showing some of the Getty buildings on a snowy winter’s night, with young, nicely-groomed POWs walking in a group to a class carrying English language study pamphlets, and the last scene, in which Lieutenant Colonel T. V. Smith hosts a roundtable discussion on his three “mighty truths” of the U.S. government, with POWs commenting on whether or not Germany could adopt them.

In an even shorter War Department video, which can be viewed at the website www.criticalpast.com (search Fort Getty), German POWs at Fort Getty are taught classes, including one by former Congressman T. V. Smith, whose students hold a book titled History of the United States. A U.S. Army sergeant teaches an English language class. POWs are seen at a graduation ceremony, with each one filing past Lieutenant Colonel Alpheus Smith and then being handed a Certificate of Achievement by Brigadier General Blackshear. M. Bryan, Assistant Provost Marshal. The filmmakers of this narrated short, intended to be viewed by the U.S. general public, intentionally did not show the