One of the oldest quarry districts in New England can be found in Westerly, where stone commonly known as Westerly White and Westerly Blue became the United States Bureau of Standards industry standard for fine grained granite suitable for monument carving due to its color and strength.

According to Mine and Quarry’s January 1913 issue:

The “White Statuary” grade [granite] is . . . used for all sorts of monumental purposes. . . . Owing to its fine grain it takes a very high polish, and at the same time is exceedingly strong. At the United States Arsenal at Watertown, Mass., in 1907, a compression test…showed a resistance of 39,750 pounds per square inch.

“Blue Westerly” [granite] is about 50 per cent less fine in texture than the white, but lends itself well to monuments. . . . It does not take so high a polish as the white, but the contrast in shades is equally good. A test on Westerly Blue shows an ultimate compression strength of 31,970 pounds per square inch.

The first quarry in Westerly to produce Westerly White and Blue granite was the Crumb Quarry, which began operations in 1834, followed in 1848, by the Smith Quarry. Orlando Smith had purchased land from Oliver Wells on what would come to be known as Quarry Hill.

Westerly granite lies in sheets up to twenty feet thick. In those early days quarrying was labor intensive as workers relied on picks, crowbars, hand drills, black powder and brute force. The key task of lifting the stones from the quarry was done by workers using teams of oxen, derricks and block and tackle pulleys. The stone was rough cut and often used for curbing, paving stones and building foundations.

Orlando died in 1859, leaving his wife, Emeline Gallup Smith, to run the business. She began to use the architectural expertise of William Burdick to expand the company’s operations to include monuments of all kinds. By the 1870s, the Smith Granite Company had become a leading producer, shipping granite monuments as far away as Chicago.

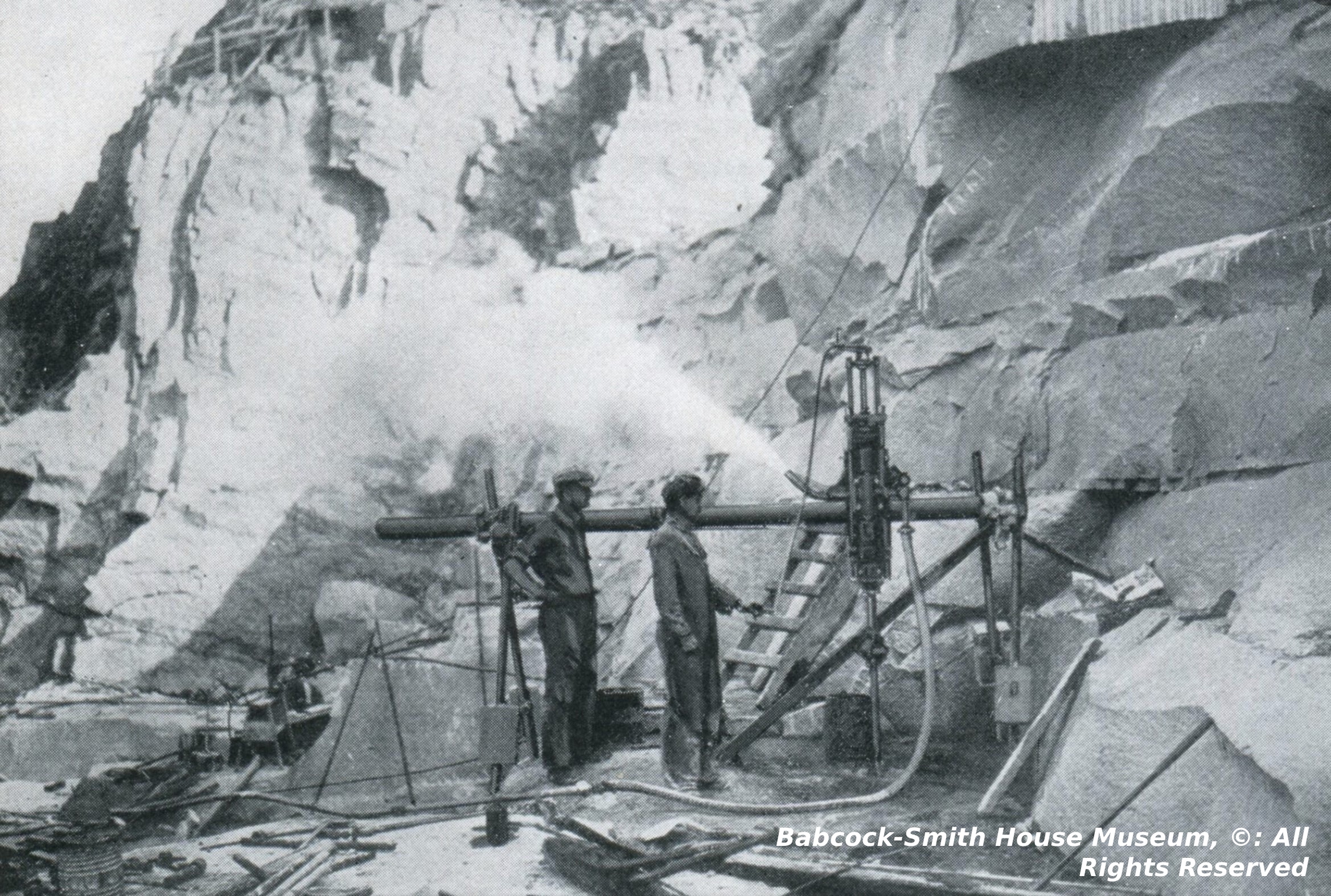

During this time, the advent of steam powered drills and derricks made the extraction of granite from quarries far more efficient. By the 1890s pneumatic equipment began to be used.

It was not only the improvements in quarrying that caused the Smith Granite Company to become a leader in the granite monument business. It was the influx of skilled craftsmen: architects, sculptors, statue carvers, letter cutters and stonecutters, many of them immigrants or second-generation immigrants, made it possible for the company to produce great works of art that by the 1880s were being transported throughout the United States. Impressively, many of the monuments erected by Union regiments at Civil War battlefields, including at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, and at Antietam Battlefield in Maryland, were made by The Smith Granite Company.

Emeline led the business for many years, an impressive achievement for a woman of that era. With the death of Emeline in 1886, the company was run by two of her sons, Isaac G. Smith and Orlando R. Smith. They incorporated the company and solidified its position as one of the leading producers of granite monuments in the country.

Smith Granite Company quarry using a steam powered drill set on a quarry bar (Babcock-Smith House Museum)

The following are two examples projects worked on by The Smith Granite Company in 1896.

In 1896, The Smith Granite Company received an order from Nicholas Brown Young for a group statue on a pedestal. The Smith Granite Company decided to use its very best stone, Smith White Statuary, to produce the monument.

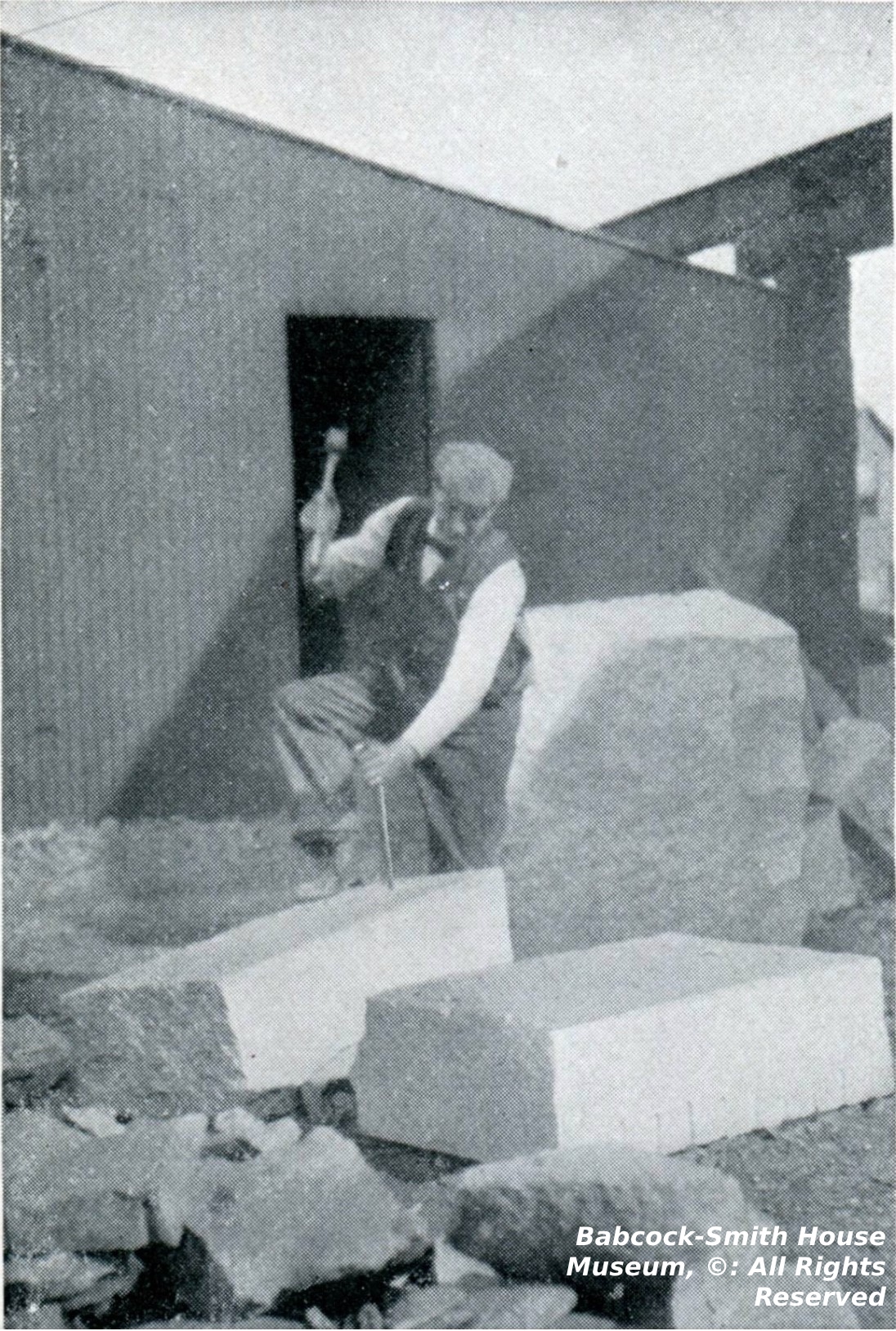

The job of producing the sculpture for the group statue was given to Robert D. Barr. He began the process by creating a clay model. Next, master statue carver James W. Pollette was given the job of carving the granite group statue using sculptor Robert D. Barr’s model as his guide.

The master workmen who performed the work were employees of The Smith Granite Company. The base of the pedestal was cut by Peter Jeffrey, the die by Mike Burke and the top by Charles Slocum. The headstone was carved by Thomas Holiday. For some reason, a new base was carved by Martin Sweeney. The name Young on the pedestal was carved by Bernard Craddick while the initials were done by Alexander McFarland. The initials on the headstone were carved by Daniel Kelliher.

When finished, the monument cost about $3,900.00 (about $145,500 in today’s money). It was shipped to and set in Swan Point Cemetery in Providence.

Young monument in Smith Granite Company order book 10, page 140, order number 288 (Babcock-Smith House Museum)

Sculptor Robert D. Barr’s clay model used to carve the Young monument statue (Babcock-Smith House Museum)

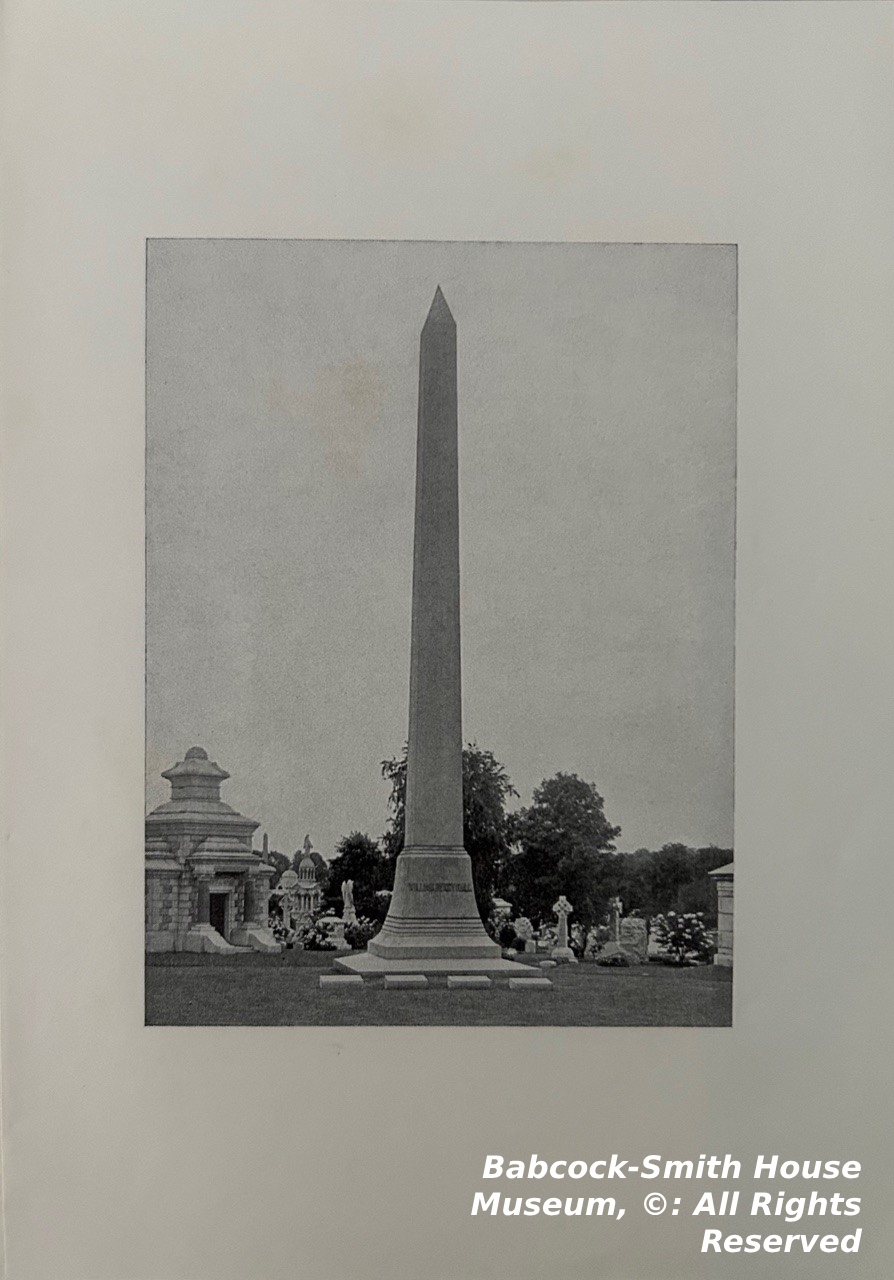

Another order The Smith Granite Company worked on in 1896 was an order placed in 1895 by the Estate of William Henry Hall for what would become the tallest obelisk on pedestal the company ever produced. When completed, the Smith Blue granite monument would stand 57 feet and 4 inches tall. The shaft (which would become the obelisk) would alone be 47 feet tall.

The Westerly Daily Sun carried an article in its April 29, 1896 edition about the quarrying of the monument. It read:

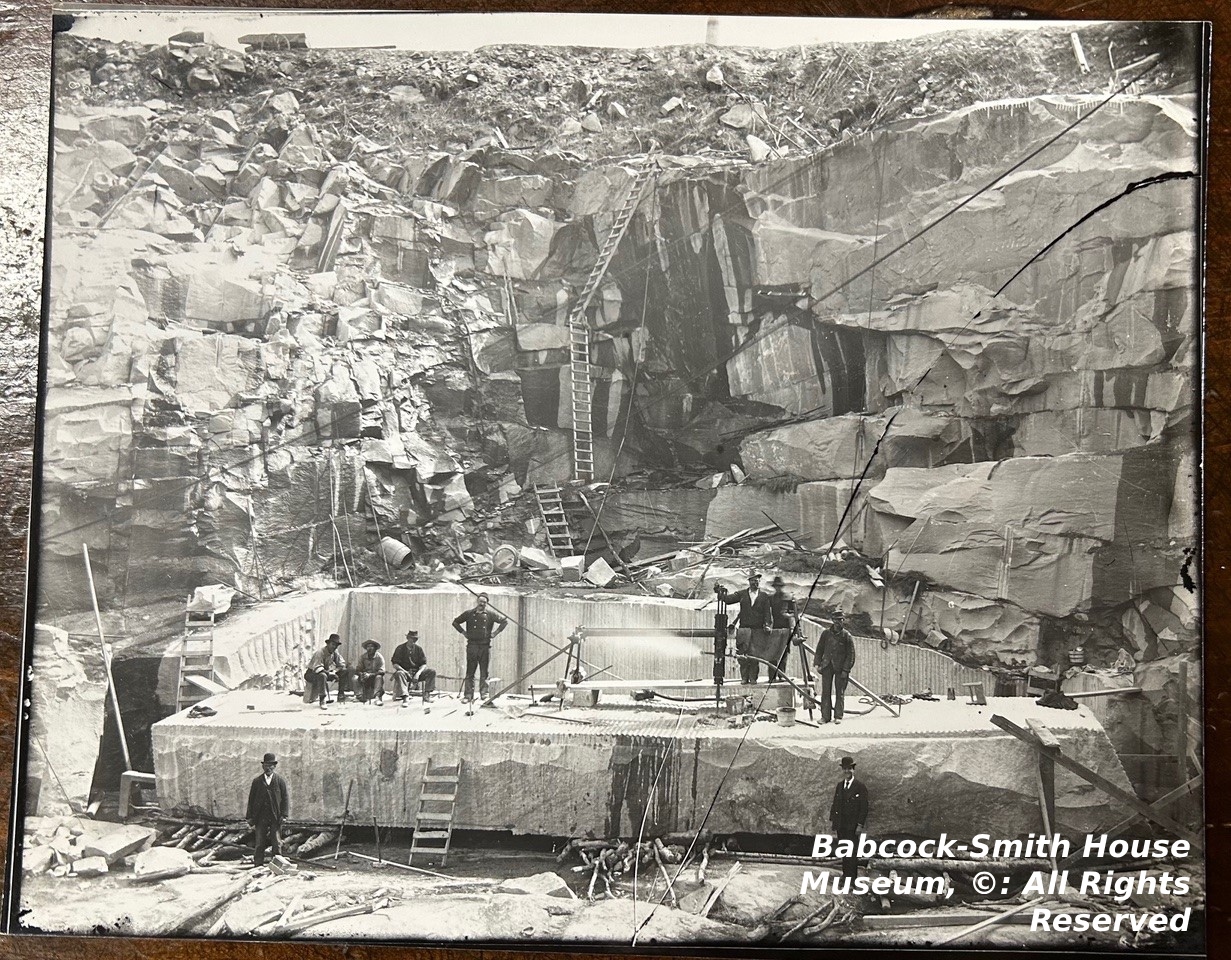

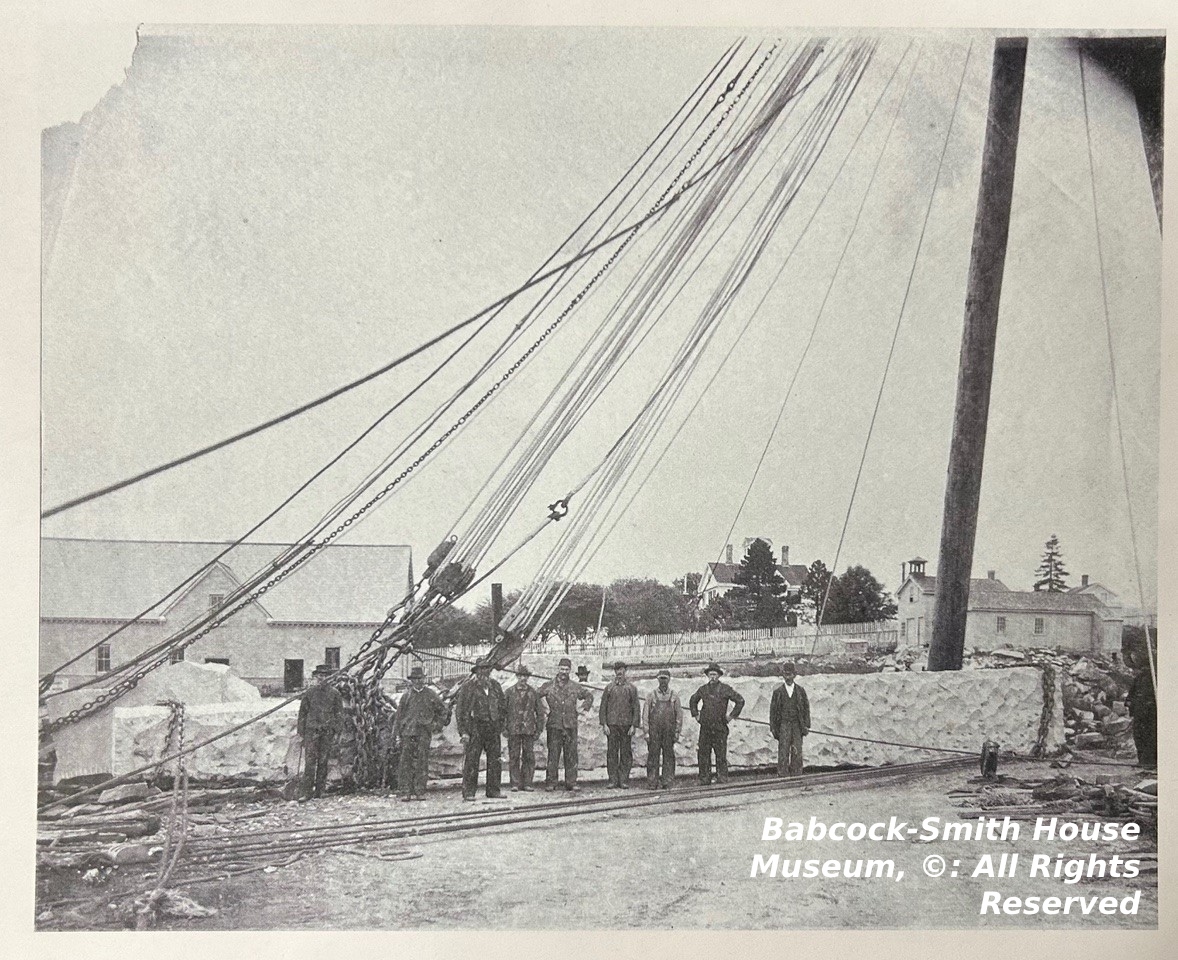

In January of this year the Smith Granite works began . . . the cutting of a long shaft, in fact the stone for two shafts. [The two shafts would become the Hall monument’s obelisk and the smaller the Proctor monument’s obelisk.] The deepest point of the hole is the southeast corner, and here, 125 feet below the surface, a gang of men, averaging twelve each working day, with a steam drill, with its incessant pounding night and day, have been laboring to obtain a block of granite 50.7 feet long, 10.4 feet high, and 4 feet thick. On April 13 success crowned the first step of their labor. The block of granite, the longest ever quarried in Westerly, was released from its fastenings and pried out from the steep wall. It was impossible to remove this large stone, and it therefore became necessary to drill out the two shafts, into which it was to be cut, while still in the hole. To do this the long block must be tipped over . . . . [S]everal cords of wood were piled up in systematic order, upon which the shaft might fall. Three heavy chains were attached to the top, and by means of hundreds of feet of cable and a dozen and a half blocks, with the horse power of hoisting engines the overthrow was accomplished on Wednesday last. Immediately a gang of hand drillers were put on with the steam drill, and the work of cutting out three pieces, two shafts—one to finish 44 feet long and 4 feet square at the butt, and the other to finish 30.4 feet long and 3.1 feet square at the butt—was begun. Extra wire cables are being rigged to the heavy derrick, and every precaution taken to secure the safe removal of the shafts from the depths to the ground above.

As the Hall shaft was lifted up and out of the quarry, logs were stacked along the quarry wall to act as a cushion so that the shaft would not be damaged during the lift.

Once the remaining pieces were in the cutting shed workmen began the process of finishing the four piece pedestal. The Smith Granite Company workers who did the tasks were as follows: the large bottom base, James Pine; the second base, John Ahern; the top base, Martin Sweeney; and the die, Joseph Smith. Henry Francis cut the large obelisk. The three headstones were cut by John Moore, John Keenan and Patrick Driscoll. John Rowe polished the monument while William Higgins polished the headstones. The lines carved into the pedestal were done by William Craig and Maurice Flynn. Flynn also carved the name on the pedestal while Joseph Fraser did the initials on the headstones.

When finished, the Hall monument cost $12,000.00 (about $448,000 in today’s money) and was shipped to and set in Woodlawn Cemetery in Bronx, New York.

Hall monument, Smith Granite Company order book 10, page 65, order number 201 (Babcock-Smith House Museum)

The Smith Granite Company index card with the dimensions of the four piece pedestal (three bases and a die) along with the obelisk (shaft) (Babcock-Smith House Museum)

Smith Granite Company quarrymen before the Hall monument block was flipped on its side. Also shown are logs to cushion its fall (in the foreground) and two of the three chains and pulleys used to make the flip (Babcock-Smith House Museum)

Smith Granite Company quarrymen using a steam drill to drill the holes necessary to split the giant block in half before the Hall half is lifted out of the quarry (Babcock-Smith House Museum)

Smith Granite Company quarrymen begin to lift the Hall monument out of the quarry (Babcock-Smith House Museum)

The Smith Granite Company quarrymen completing the lift out of the quarry (Babcock-Smith House Museum)

The Smith Granite Company Hall shaft ready to be turned into a finished obelisk (Babcock-Smith House Museum)

The Hall obelisk on a pedestal set in Woodlawn Cemetery, Bronx, New York (Babcock-Smith House Museum)

The Smith Granite Company’s first great sculptor, Edward Ludwig Albert Pausch, began his career in Hartford, when at the age of 14 he started as an apprentice working for sculptor Carl Henry Conrads, the chief sculptor for New England Granite Works, owned by James Goodwin Batterson. By 1889, Pausch had moved to Westerly, to begin his work as a sculptor for The Smith Granite Company. (Pausch would later train Robert D. Barr and Edward Stanley, both of who would become master sculptors for Smith Granite.)

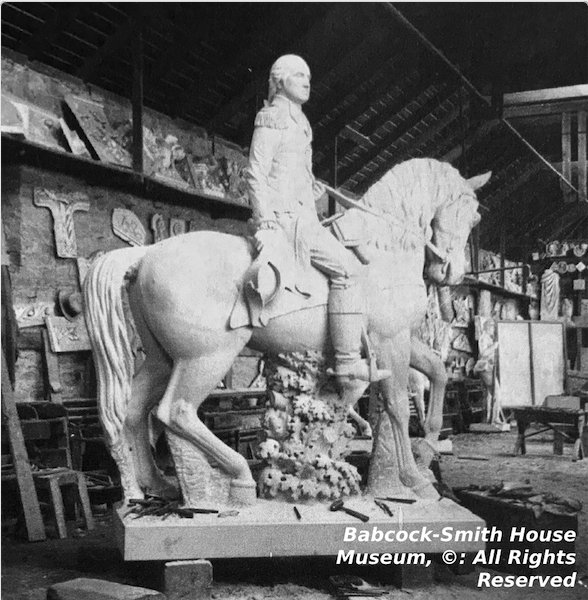

In 1889, Pausch was given the job of sculpting the model for what was to become the largest granite equestrian statue ever produced, a nine foot and six inches tall statue of a young George Washington astride a horse, when Washington was an aide-de-camp to British General Edward Braddock during the French and Indian War. It was to be placed upon a 7’ 7” pedestal, in Allegheny Park, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Using Pausch’s model sculpture, master statue carver Angelo Zerbarini carved the statue using Westerly Blue granite. The legs of the horse remained unfinished to give the statue more stability during shipping. Zerbarini thus also made the trip to Pittsburgh and finished the carving there.

The five piece pedestal was cut as follows: the large bottom base by Henry Edwards and William Wills, the second base by Martin Sweeney, the third base by Samuel Slocum, the die by Joseph Bottinelli, and the top by Richard Datson. The carving on the die was done by Antonio Comi, except for the rear side, which was done by William John Veal. Lettering was done by Richard Roediger while the jobbing was done by William Norman and Daniel Kelliher.

When Angelo Zerbarini finished the statue and the entire monument was set in Allegheny Park in Pittsburgh, its total cost amounted to $10,000.00 (about $344,500) in today’s money.

George Washington Equestrian monument, Smith Granite Company order book 6, page 77, order number 235 (Babcock-Smith House Museum)

George Washington Equestrian Monument in the Smith Granite Company carving shed ready to be boxed and shipped to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (Babcock-Smith House Museum)

Smith Granite Company advertisement showing the George Washington Equestrian Monument in Allegheny Park, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Note branch offices located in Boston, Providence, New Haven, Utica, Cleveland, and Chicago (Babcock-Smith House Museum)

By 1922 Orlando R. Smith Jr. had become president of the company. With the death of James G. Batterson in 1924, Orlando R. Smith Jr. bought the New England Granite Works’ Westerly operations. That company had been The Smith Granite Company’s main competitor since the late 1860s and had shared two of the quarries on Quarry Hill with the Smith company.

Like so many granite companies across the nation, The Smith Granite Company was hit hard by the Great Depression. Just as those lean years were coming to a close the Great Hurricane of 1938 struck, causing a sustained loss of power and beginning the process of the deep quarries filling with water. The company tried to recover, but then World War II brought rationing and a further decline in orders. In 1945, the year World War II ended, the once great company had many of its assets foreclosed upon and it was forced into receivership. For the next ten years, the company was allowed to fill orders and sell its assets after that was completed. By 1955, The Smith Granite Company officially went out of business.

The Smith Granite Company buildings and quarries on Quarry Hill, Westerly, circa 1911 (Babcock-Smith House Museum)

At that time, the last Smith family member still working in the Westerly granite industry, Isaac Gallup Smith, Jr., made it his life’s work to save as much of the local granite history as he could for future generations to learn about. He kept the 22 Smith Granite Company order books that contain the orders the company received from 1881 to 1955. They make up the most complete records of any of the great granite companies that operated during the golden age of granite monument manufacturing in this country. These documents, as well as many related photographs, including the old ones used in this article, are held by the Babcock-Smith House Museum at 124 Granite Street in Westerly.

Note:

The Babcock-Smith House Museum owns all of the photographs in this article, ©: All rights reserved. Please do not use without the permission from the Babcock-Smith House Museum.