These three ministers helped shape colonial and revolutionary Rhode Island. The first was the minister of the Second Congregational Church in Newport, Reverence Dr. Ezra Stiles. The second was the minister of the First Congregational Church in Newport, Samuel Hopkins. The third was the Baptist minister who played a key role in founding Rhode Island College, what is now Brown University, James Manning.

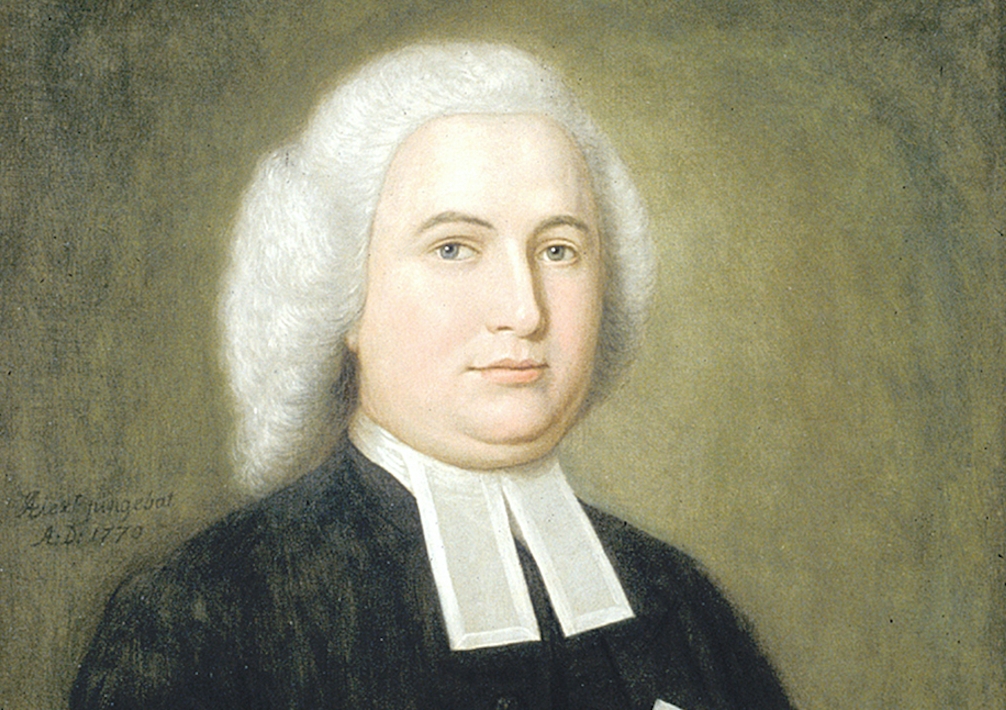

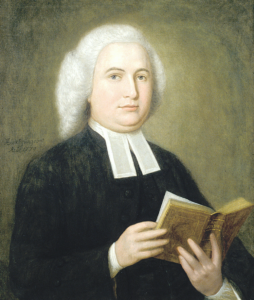

Reverend Dr. Ezra Stiles

Ezra Stiles (1727-1795) was born in North Haven, Connecticut, the son of Isaac Stiles, a Yale-educated Congregational minister, and Kezia Taylor, who died five days after his birth. Ezra entered Yale himself at age fifteen and graduated at nineteen in 1746. Three years later he entered the ministry. As a young man he also studied and practiced law and conducted experiments in electricity in correspondence with Benjamin Franklin.

In 1755, at the age of twenty-eight, Stiles took an assignment as minister of Newport’s Second Congregational Church, where he served with distinction for over two decades. Small in stature and of “a very delicate structure,” Stiles was nonetheless a first-rate preacher, described by contemporaries as “always tolerant and distressed by sectarian bickering.”

During his tenure in Newport, Stiles became an intellectual and civic leader. He served as librarian of the Redwood Library and, though a Congregationalist, wrote the initial draft of the charter for the Baptist-sponsored Rhode Island College (later Brown University). His draft called for mutual tolerance and religious liberty and prohibited all religious tests for either faculty or students. At various times he attended Quaker, Jewish, Dutch Reformed, Anglican, and Catholic services to acquaint himself with those religions.

Although a minister, dedicated much of his life to accumulating knowledge. He conducted scientific experiments, studied local Native American culture, and taught himself Hebrew. His biographer, Edmund S. Morgan, called him a “monstrous warehouse of knowledge.”

Stiles became a spokesman for the patriot cause in the decade prior to the American Revolution. He left Newport for nearby Dighton, Massachusetts, before December 1776 when the British came to occupy Newport. During 1777 and early 1778 he served as pastor of the Congregational church in Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

While in Newport, in 1756, Stiles acquired an enslaved ten-year-old boy from one of his slave-trading parishioners. Stiles named him Newport. Stiles freed Newport in 1778. Stiles supported schemes to educate African Americans and, occasionally, anti-slave trading proposals by the Reverend Samuel Hopkins (see below).

An indefatigable note-taker and writer, in 1769 Stiles began a literary diary that would reach fifteen volumes by the time of his death in 1795. This record is a major source for events in pre-Revolutionary Rhode Island and for the progress of the war in New England. In addition, Stiles wrote six volumes of manuscript notes on this travels (“Itineraries”) from 1760 to 1794 and a host of other papers which he donated to the archives of Yale University.

Because of his reputation as one of the most literate and learned men in New England, Stiles was called to his alma mater, Yale, in 1778 to become its president and a professor of ecclesiastical history and Semitic languages. His knowledge of Hebrew–acquired by his intellectual interaction with Rabbi Haim Isaac Carigal, Rabbi Isaac Touro, and other members of Newport’s Jewish synagogue–allowed him to translate large portions of the Old Testament into English. In his later years his sermons and writings were notable for their espousal of democracy and their opposition to slavery. Stiles engaged in an impressive variety of intellectual pursuits during his career: he was a linguist (Hebrew, Arabic, Syriac, Armenian, and French), an amateur scientist (electricity, astronomy, chemistry, and zoology), a theologian, and an ecclesiastical historian.

Stiles married twice, first to Elizabeth Hubbard of New Haven in 1757. Of the eight children she bore him prior to her death in 1775, only five outlived their father. In 1782 he married Mary (Cranston) Checkley, a widow; the daughter of Benjamin Cranston of Newport, she was a member of one of the town’s leading families.

In May 1795, at the age of sixty-seven, the still active and enormously productive Stiles contracted a fever and died within a week. His notable career is detailed in a fine biography by Edmund S. Morgan appropriately entitled The Gentle Puritan (1962). Though altered the Stiles house in Newport, at 14 Clarke Street, has been preserved.

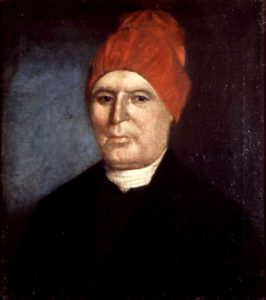

Reverend Samuel Hopkins

Samuel Hopkins (1721-1803) was a Congregational theologian and reformer. He was born in Waterbury, Connecticut, the son of Timothy Hopkins, a successful farmer with the financial means to send young Samuel to Yale, from which he graduated in 1741. During his senior year at Yale, then operating under Congregational auspices, Hopkins became caught up in the religious revivalism that has come to be known as the Great Awakening. He later claimed to have experienced spiritual conversion at that time.

In 1741 he moved to Northampton, Massachusetts, to prepare for the ministry under the tutelage of the famed revivalist Jonathan Edwards. Two years later Hopkins accepted the pastorate of the congregation at Great Barrington, Massachusetts (then Housatonic), thus beginning a twenty-six-year ministry on the New England frontier. There, in 1748, he married Joanna Ingersoll, with whom he had eight children.

While serving at Great Barrington, Hopkins published two major theological works that made him the leader of an innovative hyper-Calvinist movement within New England Congregationalism, a movement that was referred to as the New Divinity or Hopkinsianism. Its doctrinal positions (e.g., God does not merely permit sin; He wills it into existence for good ends) and its concept of immediate conversion (a tenet that seemed to diminish the importance of the means of grace–namely prayer, Bible reading, and church attendance) prompted increasing criticism, especially from Hopkins’s own congregation. In addition, Hopkins was a studious, learned minister, not a skilled or inspiring preacher or an effective revivalist. These factors contributed to his dismissal from rural Great Barrington in 1769 and his momentous move to cosmopolitan Newport’s First Congregational Church.

Hopkins labored in this seaport town for thirty-three years until his death in 1803. In Newport he not only continued to develop the New Divinity and formulated his doctrine of disinterested benevolence, a radical selflessness for the glory of God and the good of humankind; he also began to see the connection between disinterested benevolence and the antislavery cause. In 1776 he published A Dialogue Concerning the Slavery of African Americans, addressed to the Continental Congress, in which he insisted that the Revolutionary cause would not prosper until freedom was extended to slaves. In the Dialogue and other pamphlets Hopkins linked the American Revolution and slavery in a framework that became a central element in the first major antislavery movement in America.

Hopkins railed against slavery despite Newport’s role as the leading port sending ships on African slave voyages in all the thirteen colonies. Many of the slave ship owners and ship captains attended Reverend Stiles church services. Hopkins worked with two other leading Rhode Island abolitionists, Moses Brown and Stephen Hopkins.

While continuing his antislavery crusade, Hopkins also made important contributions to his theology of the New Divinity, especially in a monumental two-volume treatise, published in 1793, entitled System of Doctrines Contained in Divine Revelation. According to his biographer Joseph Conforti, “Hopkins was among the most original theologians America has produced.” His New Divinity movement came to dominate New England Congregationalism during the first two decades of the nineteenth century; “his doctrine of disinterested benevolence helped inspire the foreign missionary movement in the United States; and his antislavery writings were republished and read by New England abolitionists.”

In 1793 his wife Joanna died, and a year later, at the age of seventy-three, he married Elizabeth West. A stroke in 1799 left Hopkins partially paralyzed, but he survived and continued his theological efforts until his death in December 1803.

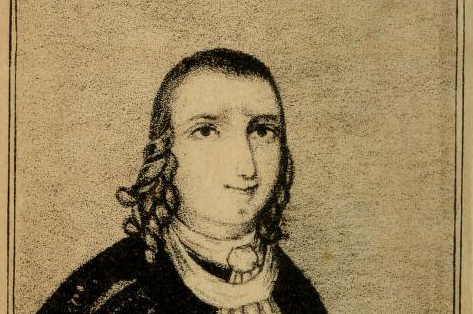

Reverend James Manning

Reverend James Manning (1738-1791), Baptist clergyman and founding president of Rhode Island College (now Brown University), was born in Elizabeth Township, New Jersey, to parents who were probably of Irish origin. He attended Hopewell Academy, a Baptist grammar school, and the College of New Jersey (now Princeton), a school that operated under Presbyterian auspices. In 1764, after ordination as a Baptist minister, Manning and his wife Margaret Stiles moved to Warren, Rhode Island, where he founded a Latin school and a Baptist church. When the region’s Baptists decided, after much debate and controversy, to establish a college in Warren, they obtained a charter from the General Assembly in 1764, after more debate and controversy. Shortly thereafter, the fellows of Rhode Island College chose the Reverend James Manning as the school’s first president. By 1770 the college’s financial problems and the persuasion of Providence civic leaders, especially Stephen Hopkins and the Brown brothers, led to its relocation, and Manning moved with it to Providence.

As a Calvinist with an evangelical spirit, Manning was more suited to action than to scholarship. However, he taught classical languages, moral philosophy, and rhetoric to his students. Under Manning’s leadership his college attracted and accommodated several religious minorities, including Quakers and Jews.

Manning enjoyed giving advice to the college’s students. At the 1773 graduation, he soundly advised them: Be slow to speak and swift to hear; be angry only when absolutely necessary, and then you will not be likely to exceed due bounds. Despise the narrow, contracted principle which actuates the selfish, and only think you deserve the character of men when you affectionately love and glow with ardor to promote the happiness of all mankind.”

Manning’s arrival in Providence caused a temporary schism in the First Baptist Church. When the pastor and some of the congregation of that church withdrew, Manning became the church’s pastor, a position he held from 1770 until 1791. Under his leadership the First Baptist Church introduced congregational singing, expanded the terms of communion to include more Baptists, and moved to a more stringent Calvinistic theology.

During his twenty-one year tenure in Providence, Manning became a prominent civic leader and even served Rhode Island as a delegate to the Confederation Congress in 1786. Although he was a reluctant revolutionary, Manning became a staunch advocate of the federal Constitution, and he was very instrumental in securing support for its ratification from Baptists in Rhode Island and in Massachusetts, a state which he had criticized for compelling Baptists to pay taxes that supported the established Congregational Church.

Joining the Providence Abolition Society in 1789, Manning was one of the earliest New England Baptists to become involved in the abolitionist movement. In April 1791 he resigned as pastor of the First Baptist Church and requested that the college find a new president. He was still serving in the latter capacity when he suffered a fatal stroke and died, childless, in July 1791.

According to his biographers, Manning’s greatest significance lies in his contributions to the institutional development of the Baptist denomination. While the college became a focus of Baptist identity, Manning worked to develop his denomination in other ways, and his influence helped reestablish Calvinism as the theological standard among New England Baptists. This Calvinism, says biographer Charles Dunn, “was not a theological straightjacket, but served as a common reference around which disparate New England Baptists could coalesce and from which they could evolve.”

[Banner image: James Manning]

For More Reading:

Morgan, Edmund S. The Gentle Puritan. A Life of Ezra Stiles, 1727-1795. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1962.

Conforti, Joseph A. Samuel Hopkins & the New Divinity Movement. Grand Rapids, MI: Christian University Press, 1981.

Ted Widmer. Brown. The History of an Idea. Providence, RI: Brown University, 2015.