This is the first article of four counting down my list of the top twenty greatest Rhode Islanders of all time. In this article, I present the greatest Rhode Islanders, numbers twenty to sixteen (with honorable mentions and current Rhode Islanders to watch). In the following weeks, I will have articles showing my list of greatest Rhode Islanders, numbers fifteen to eleven, ten to six, and, finally, the top five.

Rhode Islanders can be proud of this top twenty list. I am safe in saying that this list is more impressive than that of any other small or lightly populated state in the country, and is more impressive than many of the medium-sized and large states. Small state big history indeed!

At the end of this article is a brief explanation of the criteria I used.

20. Thomas Corcoran (1899-1981)

Thomas G. “Tommy the Cork” Corcoran was born in a middle-class Irish-American family in Pawtucket. His father, the son of an Irish immigrant, was a leading lawyer and Democratic politician. He adopted the Democratic politics of his father and Catholic religion of both parents. At age fifteen, he worked on a farm for fifteen cents an hour, and led a strike for better pay and was fired. Corcoran attended Brown University, where he was a football star, president of the debate club, class vice president, an accomplished pianist, a star of stage plays, and class valedictorian. After earning high grades from Harvard Law School and being the first Irish-American to be selected as an editor of the Law Review, in 1926 Corcoran clerked with the great Supreme Court justice Oliver Wendell Holmes. Holmes advised him, according to Corcoran, who took the advice to heart, “Never, never reach for title, for there will always be others who want it. Instead, aspire to command.” Always taking modest governmental posts, he helped to write the Securities Act of 1933, which still today regulates the issuance of stock by companies, and other key New Deal legislation that had a wide national impact. In 1935 Corcoran became an intimate with President Franklin Roosevelt, not only advising him, but relaxing him by singing Irish ballads and playing the piano and accordion. Roosevelt called him “Tommy the cork,” and Corcoran called him “Skipper.” Once, after dazzling a group of senators, Roosevelt exclaimed, “By God, you’re the first man I’ve had who could handle himself on the Hill.” He even wrote some of Roosevelt’s best lines, including the phrase, “rendezvous with destiny.” Roosevelt’s son, Elliott, wrote that Corcoran “had a major hand in most items of New Deal legislation” and “apart from my father, Tom was the single most influential individual in the country.” Corcoran and associate Benjamin Cohen, known as the “Gold Dust” twins, appeared on the cover of Time magazine’s September 12, 1938 edition. But due to power struggles inside the White House, and his earning the enmity of some Congressional leaders, Corcoran lost the President’s favor and resigned his government post. During World War II, he played a pivotal role in establishing a group of American volunteers known as the Flying Tigers, who supported China against Japan’s invasion. Using his incredible Washington, D.C. connections, Corcoran became the first modern super-lobbyist, representing oil companies, pharmaceutical companies, and other big businesses. For the next forty years, Corcoran served as Washington’s premier behind-the-scenes horse-trader, fixer and power broker. He was the first to understand the symbiotic relationship among the executive branch, Congress and corporate America. He never sought political office in Rhode Island because he already had access to the pinnacles of power. President Harry Truman had his telephone illegally wiretapped by the FBI for two years in order to gain intelligence about his political enemies. Corcoran was among those who persuaded John F. Kenned to pick Lyndon Johnson as his vice-president. To read more: David McKean, Tommy the Cork: Washington’s Ultimate Insider from Roosevelt to Reagan (Steerforth, 2003) and Peddling Influence: Thomas “Tommy the Cork” Corcoran and the Birth of Modern Lobbying (Steerforth, 2005).

19. Zachariah Allen (1795-1882)

Born in Providence, he graduated from Brown University in 1813 and married Eliza Harriet Arnold in 1817. An inventor, in 1821 he constructed the first hot-air furnace for the heating of homes and in 1833 he patented his best-known device, the automatic cut-off valve for steam engines. Fires at mills and other manufacturing plants were then a terrible hazard for both workers and owners. With his own mill in what is now North Providence, Allen added various fire safety devices that were advanced for the time. The Allendale Mill included stone construction, a sprinkler system, heavy fire doors, and a hydrant. He installed the first rotary fire pump, copper-riveted fire hose, and central heating to eliminate the need for individual stoves on each work floor. In addition, Allen built a heavy firewall separating the picker room, an area filled with highly flammable cotton fibers and lint that often led to fires, from the rest of the mill. Finally, he roofed the structure with slate roof shingles set in mortar. Thus, Allen became a pioneer in workplace safety and fire protection that influenced other mill and commercial building owners throughout the country. He then asked for a reduction in his insurance premiums but was denied. So Allen turned to other mill owners who shared his loss-prevention philosophy and together in 1835 they formed Manufacturers’ Mutual Fire Insurance Company. Fire prevention, regular fire safety inspections, and studying industrial fire hazards resulted in fewer losses and lower premiums. But because one mutual company could not handle the financial impact of the loss of an entire plant, Allen formed another insurer, Rhode Island Mutual, in 1848. More mutuals were formed in New England over the next two decades. There were ultimately forty-two insurers that were part of the Factory Mutual System. Those companies consolidated over time until they finally merged into one company, FM Global, which operates today with headquarters in Johnston. Allen also originated the Providence Water Works and is credited with introducing the first vehicles to the Providence Fire Company. He was active as one of the founders of the Providence Anthenaeum in 1831 and the Rhode Island Historical Society in 1822, and he helped to establish Roger Williams Park. For further reading: Paul F. Caranci, North Providence: A History & the People (History Press, 2012).

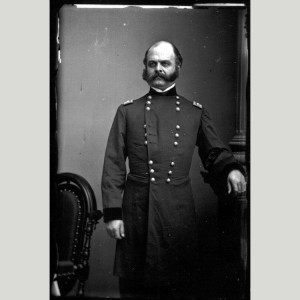

18. Ambrose E. Burnside (1824-1881)

Born in Indiana in 1824, he graduated from West Point in 1847. After serving in the Mexican-American War, in 1852, he was assigned to Fort Adams in Newport, and while there he married March Richmond Bishop of Providence. In 1853 he resigned his commission and founded a company in Bristol, Rhode Island producing breech-loading rifles. His business failed after a fire destroyed his factory, but when the Civil War began, he rushed to Washington, D.C. his Rhode Island infantry regiment, which was one of the first to arrive in the nation’s then virtually undefended capital. He succeeded in a North Carolina coastal campaign in 1861, which led to his promotion as major general in 1862. Commanding a corps of the army at the Battle of Antietam, he was made commander of the Army of the Potomac after George McClellan was sacked in November of 1862. A month later, however, Confederate general Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia soundly defeated Burnside and his troops at the Battle of Fredericksburg, a lopsided and tragic defeat that resulted in more than 13,000 Union casualties. Burnside was relieved as commander, but in 1863 he succeeded in holding Knoxville, Tennessee, against an army commanded by General James Longstreet. Back in good graces, Burnside served in Virginia as a senior commander of the Army of the Potomac under General Ulysses S. Grant for most of the remainder of the war. But after he failed to exploit an opening at the Battle of the Crater outside Richmond, Virginia, he resigned shortly before the end of the war. He was not a battlefield genius or a natural leader, but he perhaps should receive more credit than he has received from most Civil War historians. In 1866, as a Republican, he was elected governor of Rhode Island for the first of three terms and then represented the state in the U.S. Senate until he died of heart disease in 1881. He is perhaps best known for popularizing the style of side-whiskers that are now called by the corrupted version of his last name, sideburns. For further reading: William Marvel, Burnside (Civil War Library, 1991).

17. John Chafee (1922-1999)

A United States Senator and Governor of Rhode Island, he also served as Secretary of the Navy. In the Senate, he made environmental matters a chief concern, as well as supporting public transportation and other liberal causes, often breaking with his Republican Party. Although a Republican in one of the most Democratic states in the country, he remained popular in Rhode Island. He was once asked if he was in the wrong party for him. Despite his disagreements with its leaders about abortion, tax cuts, gun control and environmental issues, he said “I’m happier being a Republican than a Democrat. That doesn’t mean I’m happy with everything the Republicans do.”

John Lester Hubbard Chafee was born October 22, 1922, in Providence to a wealthy and politically active family. His great-grandfather Henry Lippitt was a Rhode Island governor, and among his great-uncles were a Rhode Island governor, Charles Lippitt, and a United States senator, Henry F. Lippitt, all Republicans. After graduating from elite Deerfield Academy in Massachusetts and starting studies at Yale University, Chafee served in the Marines during World War II in the brutal battles at Guadalcanal and Okinawa. He finished his degree from Yale in 1947 and graduated from Harvard University law school in 1950. Then he rejoined the military, serving as a Marine rifle company commander in the Korean War. He successfully ran for a seat in the Rhode Island House of Representatives in 1956 and later became the minority leader. He was reelected in 1958 and 1960, the latter a year when many Republicans were swept from statewide office. He was elected governor in 1962 and was an unabashed liberal. He pushed for anti-discrimination laws in housing and employment before the federal government passed them. He advocated the construction of Interstate 95, developed parks throughout the state, and pushed through a state plan of health care for the elderly before Congress enacted Medicare. He was defeated in his bid for reelection as governor in 1968 after advocating a state income tax, which did pass a few years later. (He had also halted his campaigning after his fourteen-year-old daughter, Tribbie, had died a few weeks before the election after being kicked in the head by a horse.) In 1969 President Richard Nixon appointed him Secretary of the Navy, a post in which Chafee reveled. His most striking decision was when he blocked any court martial of the commander and the intelligence officer of the Pueblo, which had been captured by North Korea in 1968. They had been held prisoner for eleven months, and Secretary Chafee said, ‘”They have suffered enough.” Moreover, he concluded that the capture was the result of a failure shared by the entire Navy chain of command. He left the Navy Department in 1972 to run, unsuccessfully, against Democratic Senator Claiborne Pell. In 1976, he filled the seat vacated by Democratic Senator John Pastore. Chafee was one of the last moderates in the U.S. Senate, willing to cross party lines if he thought legislation was in the nation’s best interests. Year after year in the 1980s, as Congress cut the budget for other social programs, he engineered expansions of Medicaid, extending coverage to millions of pregnant women, children, and the disabled. In 1990, he played a central role in reauthorizing the Clean Air Act, one of the nation’s landmark environmental laws. After announcing he would not run in the 2000 election, he died of heart failure in 1999. His son Lincoln was appointed to replace him and won election in his own right in 2000. John Chafee was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Clinton. Among the buildings and places named after him include The John H. Chafee National Wildlife Refuge, a 550-acre refuge established on Narrow River to protect the wintering population of American black ducks.

16. John O. Pastore (1907 – 2000)

John O. Pastore, the first Italian-American to be elected as governor of, and United States senator from, any state in the nation, was a dominant figure in Rhode Island politics for three decades. ”Rhode Island is the smallest state in the union, and I am the smallest governor in the United States,” the 5-foot-4-inch Mr. Pastore once told a group of German editors visiting the statehouse in Providence. When he went to Washington, he became the smallest senator. But in his twenty-six years in the Senate, he established himself as a formidable presence, a liberal Democrat regarded as a fierce debater with a firm grasp on the issues of his day. He staked out a specialty in nuclear power matters as chairman of the powerful Joint Committee on Atomic Energy and in 1963 provided important backing for the Kennedy administration’s controversial treaty with the Soviet Union barring nuclear tests in the atmosphere. The booming orator made a stem-winding speech as keynote speaker at the 1964 Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City. His attack on Republican presidential nominee Barry Goldwater, eloquent recollections of the recently slain President John F. Kennedy, and ringing defense of the policies and person of the soon-to-be 1964 Democratic presidential nominee, Lyndon Johnson, brought the convention to its feet with a roar and resulted in his being considered briefly as candidate for vice president. He was also a prominent floor leader in the successful fight for some of the most controversial portions of the historic Civil Rights Act of 1964.

John Orlando Pastore was born in Federal Hill in Providence in 1907. His father, an immigrant tailor from Potenza in southern Italy, died when he was nine years old. His mother raised her five children working as a seamstress (explaining why Pastore as an adult was always immaculately dressed). He attended Classical High School. In 1927, while working as a $15-a-week claims adjuster for the Narragansett Electric Company, he enrolled in evening law school classes offered by Boston’s Northeastern University at a Providence Y.M.C.A. In 1932 he set up a law office in the basement of the family home, but with the Depression in full force, he attracted few clients. Benefitting from the increasing political power of the state’s Italian-American community, in 1934, he was elected to the Rhode Island House of Representatives and won reelection in 1936. In 1937 and 1938, and again from 1940 to 1944, he served as an assistant state attorney general. In 1944, he was elected lieutenant governor of Rhode Island, becoming governor in 1945 when the incumbent, J. Howard McGrath, resigned to become U.S. solicitor general. Pastore won the governorship on his own in 1946 and again in 1948. His success was attributed to his honesty, oratory, his good relations with the press, and his ability to keep his finger on the political pulse of the voter. One of his methods of doing this was to eat lunch each day in the statehouse cafeteria. In 1950, he won election to a two-year term in the U.S. Senate after a vacancy caused by the resignation, again, of McGrath. Pastore was elected to a full six-year term in 1952 and won landslide reelection victories in 1958, 1964, and 1970. He did not run for reelection in 1976 and resigned his seat in December of that year. In his retirement, he lived in Cranston and Narragansett, before passing away at the age of 93. What you can see today: The John O. Pastore Federal Building, the courthouse house for the United States District Court for Rhode Island, in Providence.

[Banner: Art deco detail from the John O. Pastore Federal Building in Providence (Library of Congress)]

Honorable Mentions (in Alphabetical Order)

Here are fifteen great Rhode Islanders who just missed making my top twenty list but still deserve honorable mention:

- Edward Bannister (1828-1901) of Providence, nationally respected African American painter of pastoral scenes

- Moses Brown (1738-1836), influential Quaker abolitionist and philanthropist from Providence, who also hired and financed Samuel Slater

- William Ellery Channing (1780-1842), influential Unitarian minister in Boston, born and raised in Newport

- George Corliss (1817-1888), inventor of an advanced steam engine, a marvel of its day

- Antoinette Downing (1904-2001) of Providence, influential in the historic preservation movement in the twentieth century

- Mary Dyer (1611-1660), early pioneer in Portsmouth and Newport who was executed by Puritan authorities in Boston in 1660 for refusing to renounce her Quaker beliefs

- George Downing (1819-1903), African American civil rights leader from Newport

- John Goddard (1723-1785) and John Townshend (1732-1809), Newport colonial cabinetmakers whose distinctive pieces with a Quaker-inspired plainness today sell for millions of dollars

- Theodore Francis Green (1867-1966), from Providence, who when he became state governor in 1935 helped to end the stranglehold of Republican rule and later served as U.S. Senator from 1937 to 1961

- Samuel Hopkins (1721-1803), influential Congregationalist minister in Newport and early abolitionist

- Napoleon (Nap or Larry) Lajoie (1874-1959), Hall of Fame baseball player from Woonsocket

- Royal Little (1896-1989), founder of Textron Inc. and pioneer of the idea of conglomerates (one company acquiring diversified businesses)

- James Mitchell Varnum (1748-1789), Revolutionary War general from East Greenwich, who was appointed a federal judge in the Northwest Territory and was an early Ohio pioneer

- Matilda Sissieretta Joyner Jones (1868-1933) of Providence, one of the great singers of the late 1800s and early 1900s who was the first African American women to sing at Carnegie Hall and performed at the White House for four Presidents

Current Rhode Islanders to Watch (in Alphabetical Order)

Here are five Rhode Islanders in the prime of their careers who one day may move up to my honorable mention list or top twenty list:

- Elizabeth Beisel of North Kingstown, Olympic and World Champion medalist in women’s swimming events

- Viola Davis of Central Falls, multiple award-winning movie, television and stage actress (African American)

- Jhumpa Lahiri Indian American acclaimed novelist who moved to the state when she was two and attended the University of Rhode Island

- Gina Raimondo of Smithfield, the state’s first elected female governor

- Dr. Rudolph E. Tanzi of Cranston, Harvard University professor leading a major effort researching Alzheimer’s disease

Criteria Used for Selections

This part explains in part the criteria I used in making my selections for my top twenty list of the Greatest Rhode Islanders of All Time.

First of all, I give the most weight to Rhode Islanders who made the greatest contribution at the national level and lesser weight to their contributions to Rhode Island. If my list was of Rhode Islanders who had the greatest impact on Rhode Island, Gilbert Stuart, among others, would not be on the list, while Thomas Wilson Dorr would probably be ranked second, and Dr. John Clarke, Theodore Francis Green, Woonsocket’s Aram Pothier, and historic preservationists Antoinette Downing and Doris Duke, among others, would be on the list.

Second, I had to define who is a Rhode Islander. I included those who were born and raised in the state, and those who moved to the state and lived in it during their periods of notable accomplishments. For example, I included Gilbert Stuart, who was born in North Kingstown and trained as a painter in Newport until he was fifteen years old (and returned to Newport for a short stint later). But I excluded George M. Cohan, who was born in Fox Point in 1878 of parents who were itinerant travelling entertainers and who left the state after he finished second grade. If I had included those simply born in the state, Cohan, the composer of favorites such as “Over There,” “Give My Regards to Broadway,” and “You’re a Grand Old Flag,” would have been in my top ten.

One feature of my top twenty list that jumps out is that, with the exceptions of Metacomet and Julia Ward Howe, each person listed was a white male, and all but four of them were Protestants (the other four were Catholics). The fact is that for most of our state’s and nation’s history, women were not allowed or encouraged to achieve greatness, but were largely relegated to the domestic sphere; and persons of color, and for much of our history, persons of different religions and ethnic backgrounds, suffered from discrimination. During most of our country’s early history, when this discrimination was at its worst, it was easier for men to accomplish a “first” and become famous. This is one of the products of discrimination: preventing talented individuals who could become great on a national level from becoming great on a national level.

There are certainly plenty of accomplished Rhode Island women and persons of color and ethnic and religious backgrounds to make up more top ten lists, which I plan to do in the future. The brilliant Puritan dissident Anne Hutchinson would have appeared on my top ten list, but I decided that she did not have a sufficient connection to Rhode Island to be considered a Rhode Islander. Her famous trial occurred when she was a Massachusetts resident. She moved to Portsmouth in April 1638 to join her supporters there and became one of the town’s founders, but so was William Coddington. After her husband’s death, Anne left Rhode Island in the summer of 1642 for Dutch-controlled New York and was killed by Indians there the next year.

Considering the historic discrimination against African Americans in the state and country, it is impressive that two of them achieved “honorable mention” status on my list. Interestingly, on my “current five Rhode Islanders to watch” list, four are women and there is substantial diversity.

After my fourth and last article in this series, I will share with you several lists that I prepared and relied in part in making my selections.