Wrapped in a blanket, a lone radio operator sat huddled in his chair on the second floor of the Massie Wireless Telegraph station at Point Judith, Rhode Island, located in the dunes at what is now the east end of Sand Hill Cove, now better known as Roger Wheeler State Beach.

It was a cold, windswept February night in early 1905. Only a small amount of warmth made its way into the second floor room through a floor grate leading to the first floor where there was a Glenwood stove. Periodically, the operator would climb up a ladder to an observation tower and peer through a telescope searching for the appearance of the Fall River Line night boat SS Plymouth headed for New York.

Suddenly, the spark of an incoming message broke the silence. CQ-PJ-D-PX. The liner’s wireless operator, also a Massie employee, was signaling the Point Judith shore station call letters PJ with his call sign PX (the Morse code letters CQ signified an outgoing call and D identifed the originating station). Incoming traffic meant revenue. A businessman aboard the ship had a telegram for a New York City client.

The Point Judith Massie station had installed poles and a land wire to connect with the Western Union telegraph several miles away at the Seaview Electric Trolley Line station in Narragansett. Quickly copying the message, the operator stepped across to his telegraph desk and relayed the message. One of the modern miracles of twentieth century communication, it was thanks in part to the innovative genius of a Providence engineer turned entrepreneur named Walter Wentworth Massie. He was a contemporary of communication pioneers such as A. Frederick Collins of Newark, New Jersey, Lee deForrest of New York, Thomas E. Clark of Detroit, and Italian-born Guglielmo Marconi (the Nobel prize winner often called the father of long-distance radio transmission). Marconi was soon to play a profound role in our story.

Telegraphy was invented by Samuel F. B. Morse. Alexander Graham Bell followed with the telephone in the 1870’s. The communications age took a dramatic turn in the 1890’s with the advent of radio telegraphy, a far more economical approach since there was no need for copper wires strung on poles. Numerous experimenters on both sides of the Atlantic developed the technology and by the turn of the century, wireless telegraphy was up and running to be followed soon by wireless voice communication and the rest, of course, is history.

Our story is about Rhode Island’s contribution, specifically that of Walter Massie.

In the early 1900’s, New York-based wireless entrepreneur Lee deForrest was travelling around the country promoting his services. The Providence Journal latched on to deForrest when its editors decided that the wealthy summer residents on Block Island would benefit from an edition of the newspaper printed on the island from material transmitted from the mainland. They hired deForrest to set up a station at Point Judith (Station “PJ”). Before the system could be completed, deForrest departed for New York to promote his services during the summer 1903 America’s Cup Races off Sandy Hook. The Journal waited patiently. In October, deForrest returned and completed the Block Island station (Station BI). The Journal began what turned out to be the world’s first wireless press system. A storm blew down the Block Island’s slender antenna tower and deForrest lost interest in the deal. The Journal needed someone with local ties to keep things in hand.

Enter Walter Massie. Well known locally for his wireless experiments and demonstrations, he replaced deForrest as the Journal’s resident wireless expert. When the Journal indicated it wanted to divest itself of the venture, Massie bought the Point Judith and Block Island stations. He had already decided that the steamships travelling from New England to New York City would benefit from wireless communications. He convinced the New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad, owners of the Fall River Line, to allow him to install a trial system aboard the steamer Pilgrim. Commencing in March of 1904, the system quickly took hold and the line commissioned Massie to install systems on the rest of the fleet’s ships. An astute businessman, Massie employed operators and placed his own equipment in specially built soundproofed cabins that were quickly duplicated on other vessels. His business rapidly expanded.

Steamers easily communicated with shore stations on Block Island, Point Judith and farther south. Soon, the steamship company owners contracted with Massie for wireless facilities on the other Providence-New York boat, Plymouth, and the Fall River-New York boats, Puritan and Priscilla. Initially, receiving signals over the longer distances was not reliable, necessitating the need to construct a number of new facilities. Gradually, transmitters and receivers improved and power increased. Atmospheric conditions also played a role.

The boats could also communicate with one another, ensuring a safer sailing environment as well as a thriving commercial enterprise. Massie’s telegraph line from the wireless station up to the trolley station at Narragansett Pier created a highly effective (and profitable) ship-to-shore network.

In June of 1904, Massie opened station “WN” at Wilson’s Point in South Norwalk, Connecticut, for the NYNY&H Railroad. The station was quickly upgraded to become even more powerful than the Block Island and Point Judith facilities and could even reach Key West, Florida. Massie also installed station HG on the roof of the Narragansett Hotel in downtown Providence. Before long, he had wireless facilities operating on both coasts serving both civilian and military interests. These stations also exchanged messages with facilities operated by other companies.

In 1907, Massie built a new, sturdy structure on the beach at Point Judith a few hundred feet away from the original rented facility. Along with several other American radio pioneers, Massie had made wireless telegraphy a household word from coast to coast and beyond.

Today Massie’s legacy lives on thanks to the New England Wireless and Steam Museum in East Greenwich (NEWSM), led by Museum Director Robert Merriam, whose staff and volunteers rescued the Point Judith wireless station from destruction in 1983 and moved it in its entirely to the museum grounds. The station’s entire operating equipment, which remained in excellent condition and had been moved earlier to a farm owned by the Massie family near Wrentham, Massachusetts, was donated by the Massie grandchildren to the museum. The equipment has been lovingly reassembled and fully restored, making Station PJ the oldest surviving example of its type in the world.

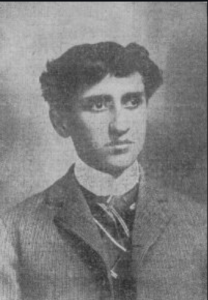

Walter W. Massie was born in 1874 to Providence banker John Massie and his wife Harriet. Young Massie began experimenting with wireless communication in 1895 while still completing his education at Brown University and Tufts University. A year later, he joined the Providence City Engineer’s Office and continued his experiments in wireless telegraphy at his home on Public Street.

He perfected and later patented a number of innovative transmitting and receiving devices that would form the basis of his entry into the burgeoning wireless business. In 1899 Massie married the former Ethel Farrington. They had two sons, Wentworth and Gardner. While working at his day job, Massie avidly continued his radio experiments. Also a talented woodworker, Massie built housings for his inventions and portable cases for public demonstrations. These display kits were also recovered from the Massie family and are now on display at NEWSM. They include a telegraph key connected to audible and visual signal devices (a doorbell and light bulb) and a device called a coherer, an early type of radio signal detector and the basis of wireless transmission systems.

A primitive form of the coherer had been developed in Europe in 1890 and was quickly put into use by a number of inventors on both sides of the Atlantic, including Marconi, who obtained a European patent for his device. A coherer is a glass tube with two electrodes, spaced apart, with metal filings in between. When a radio signal is applied to the coherer, the magnetized metal filings come together or “cohere,” which reduces resistance and allows an electrical current to pass through it. The current triggers a signaling device, such as a bell or light bulb or a paper tape strip on which a record can be made of the signal.

Massie’s coherer proved to be more sensitive and durable than those of his contemporaries. He later received U.S. patents for this invention and several related devices in 1905.

In the midst of his early research, Massie gave a lecture in the Olneyville section of Providence along with several men who were working for Lee deForrest, a New York-based radio pioneer. This brought him to the attention of other major experimenters in the field.

In an article published in the July 29, 1905 edition of Electrical World and Engineer Magazine, another well-known radio engineer, A. Frederick Collins, credits Massie for taking what was considered theoretical in nature and turning it into a “workable apparatus.” The June-July 1910 edition of National Magazine recounts Massie’s personal intervention in obtaining help for victims of a collision between two steamships in the fog off Cape Cod. A Massie operator at the Point Judith station picked up a distress call from one of the ships. Massie himself contacted a New London marine rescue company, which immediately dispatched help to the scene. This was to be repeated countless times over the years as radiotelegraphy grew in importance.

Backed by patents on his key inventions and with additional investors, Massie incorporated his Providence-based business and things really took off. Within a few years, Massie stations were installed on numerous civilian vessels and shore stations on both coasts, including wireless installations for the US Navy as far away as Alaska and the Philippines.

Massie’s sturdy, two-story frame and wood-shingled, gable roofed building at Point Judith was set on a stone foundation behind protective sand dunes inside the Harbor of Refuge and a short distance above the shoreline of Sand Hill Cove (now Roger Wheeler State Beach). The structure with its observation tower has been perfectly restored by the museum. Built to withstand the treacherous New England weather, the building survived many storms and several major hurricanes over the decades.

The original Massie Station at Point Judith, now restored and held by the New England Wireless and Steam Museum at East Greenwich (Brian L. Wallin)

With four rooms (two up and two down) and paneled in dark pine, the building offered primitive living conditions for the operators who individually manned the station around the clock. An outdoor privy was located in the dunes. In addition to windows offering a panoramic view of Rhode Island Sound, the building included a small observation tower at one end of the roofline, reached by a drop-down ceiling ladder. The station’s antenna tower was wood lattice, four feet square and 300 feet tall supporting an elaborate wire antenna array (the Museum has a scale model of a tower section).

In 1910, Massie joined forces with companies owned by fellow radio pioneers deForrest, and Collins, along with Thomas Clark of Detroit, to incorporate as the Continental Wireless and Telegraphy Company with a view to establishing a coast-to-coast communications network. But, before the new venture could take hold, disaster struck in the form of crippling industry-wide lawsuits filed by Marconi against Massie and other American wireless company owners, charging patent infringement.

Marconi was relentless in his efforts and soon put his competition out of business. By 1912, Massie had closed his Point Judith station, as well as others, and sold out to the American Marconi Company. Although he was offered a job with the Marconi interests, Massie declined and returned to work as a civil engineer in Providence.

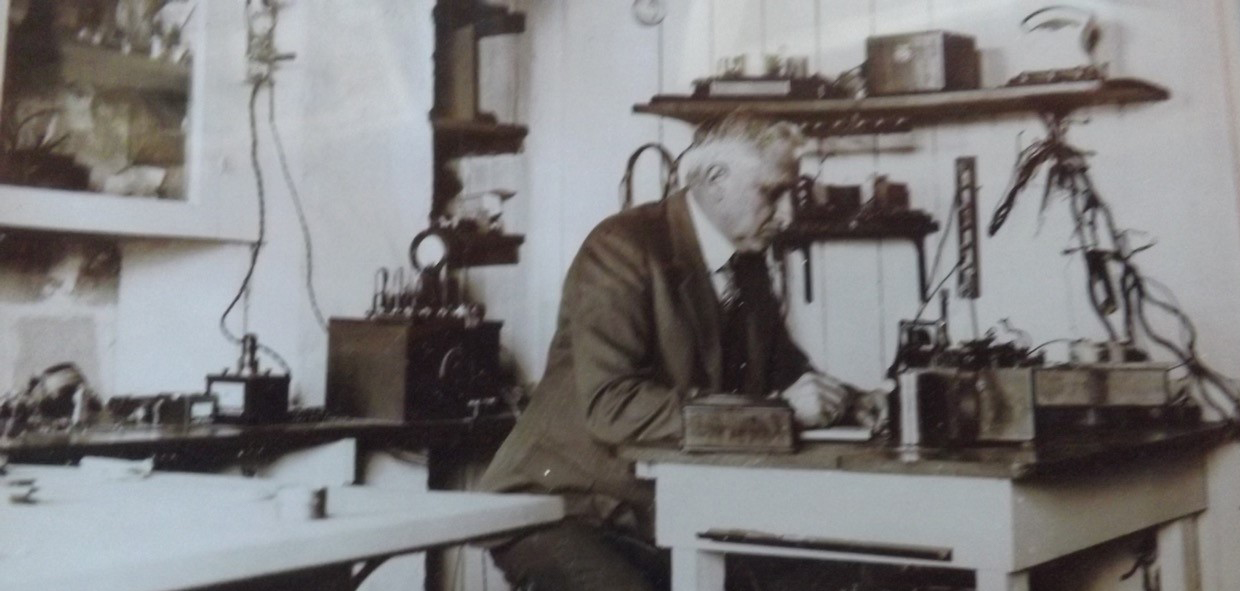

Massie remained active in radio, serving as a communications officer in the Naval Reserve in World War I. He was instrumental in forming numerous professional organizations and for a number of years after the war served as City Engineer in Cranston. He also operated a radio consultancy business in the Edgewood section of Cranston and became an avid yachtsman on Narragansett Bay. He owned a handsome motor yacht, Maurence, named after his two sisters. (Needless to say, his craft was wireless-equipped.) Massie installed a wireless system at the Rhode Island Yacht Club, where he also served as commodore for a number of years. From his office-workshop in Pawtuxet (overlooking the yacht club), he continued to build and lease powerful wireless systems to marine and commercial interests into the 1930’s.

Massie died in 1941. He, his wife and their two sons are buried in a simple plot in North Kingstown’s Elm Grove Cemetery. If it were not for the efforts of Bob Merriam and the NEWSM, his family gravesite would be his only monument.

The Marconi lawsuits continued to work their way through the courts. In 1943, two years after Massie’s death, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned a series of lower court decisions and restored to his estate some of the prior patents challenged by Marconi. But by that time Marconi, Massie and all the other American inventors named as defendants in the suit had died as well (Marconi in 1937 in his native Italy). The high court did state that its decision determined only that Marconi’s claim to certain patents was in question. It did not challenge Marconi’s claim to be the first to achieve radio transmission.

Interestingly, while Marconi never visited Rhode Island, the state’s large Italian-American population wanted to commemorate him. In the late l930’s, after Marconi’s death, a campaign was undertaken to build a memorial for him at Roger Williams Park. World War II interrupted the effort and the memorial was not dedicated until 1953.

Another and more unusual memorial to Marconi is located at the Cranston-Johnston town line at the corner of Atwood Avenue and Plainfield Streets. It is a four-sided marble base with a metal radio tower. When it was dedicated in 2001, a radio signal was actually transmitted at 94.7 megahertz on the FM band. The marble base was vandalized and a section with a replica of a transatlantic map stolen in 2005. A broken water main in 2011 silenced the transmitter, but the monument still stands. Walter Massie was a believer in spiritualism. One wonders, did Walter Massie’s spirit haunt the memorial?

How did the Massie wireless station make its way from the shores of Rhode Island Sound to a rural field in East Greenwich? That’s where NEWSM founder Bob Merriam and his dedicated band of volunteers enter the story.

When Station PJ was shut down, Massie removed all the equipment and furnishings. The building itself became a summer residence until the mid-twentieth century. Because Massie had used rough-hewn lumber and constructed an exceptionally strong and well-anchored building, it survived at least three major hurricanes. By the early 1980’s, the government decreed that the building could no longer be occupied.

Recognizing its significance, Providence architectural historian Antoinette Downing led an effort to preserve the building. According to Robert Merriam, “When Antoinette spoke, people listened.” And they responded. The owners of the building, Mrs. and Mrs. Al Cellemme of East Greenwich, cooperated with the government’s demand that the building be removed and donated the structure to the NEWSM.

“In the spring of 1983, with a group of volunteers and some major construction and transport equipment generously provided by local businesses, we took the building apart in three sections,” recalled Merriam. “A heavy crane from the Rhode Island Engine Company put each piece on flatbed trailers, loaned by Kingston Turf Farm. Under police escort, the old building was gently moved up Route 1 to our grounds in East Greenwich.”

“Then,” continued Merriam, “the real work began. Assisted by the US Navy Seabees and their heavy equipment, we built a cement foundation and reassembled the building.” Merriam and his wife Nancy had been in touch with the Massie grandchildren who had located the interior contents of the old station at the Massie farm in Massachusetts.

“Unbelievably, the family gave us a treasure trove of period wireless equipment,” said Merriam. “It was like a time capsule. Everything was there: Massie’s hand-built transmitter and receiver, the glass capacitors in their case, his Reasonaphone signal receiver and coherer gear, some of his portable demonstration kits and more, even the wireless station’s wall clock, furniture and land telegraph set-up. It was just waiting to be reassembled.” After months of research and work, Merriam and his volunteers threw a switch and, amazingly, the equipment came to life for the first time in more than seven decades.

The Massie station operates at a frequency of 350 kilocycles, below the AM radio band. If allowed to transmit, it would have an output of about 200 watts. In the early days of wireless communication, wireless stations were not government regulated. “Of course, now, we would have to be licensed by the FCC,” commented Merriam. “The FCC would no longer allow operating the station as it was designed and on the wavelength involved. Although, on one occasion, permission was granted to connect the transmitter to an antenna and the signal went out over the airwaves.” We really wanted to see it if still worked, and it did,” Merriam chucked with not a little (understandable) pride.

The building, now on the National Register of Historic Places, appears just as it existed over one hundred years ago with its weathered shingle exterior and the small windowed observation tower. Where the operator’s living quarters would have been on the first floor, there are examples of period wireless gear and Merriam’s own modern amateur radio station (call letters W1NTE).

Spark from a transmitter at the Massie Wireless Station, now at the New England Steam and Wireless Museum in East Greenwich (Brian L. Wallin)

At the time the station began operating, there was no electric service to Point Judith. The equipment was powered by dozens of 600-ampere hour capacity Edison LaLande wet cell batteries, several of which are on display. By 1909, power was supplied by a two-kilowatt gasoline generator. Eventually, an electric power line was run to the building.

A dark, narrow staircase takes visitors to the second floor radio room. In one corner is the heavy wooden table holding Massie’s equipment, just as it appeared over a century ago. On top of the bulky condenser cabinet with its glass capacitor panels is a metal helix coil that generates the transmitter spark directly to the antenna.

A heavy “pump handle” style transmitter key sends an impressive loud and visible spark to the point where it would have travelled to an outside antenna. In the opposite corner of the room is the landline telegraph station. An oddity is the presence of empty tobacco cans on the apparatus. The operators used these as a primitive form of amplifier. For telegraph equipment located by railroad tracks, the cans also created a sound that was different from the “clickety-clack” of train wheels on the tracks, thereby enabling the telegraph operator to separate the incoming signal from outside noises.

Today we take our modern communications technologies for granted. But, a little more than a century ago, pioneers like Walter Massie had a vision: a nationwide, and even international, network that would link people together like never before. The New England Wireless and Steam Museum preserves their dedication and imagination.

Bob Merriam, in restoring the Massie wireless station and its equipment, has ensured that the Providence native’s legacy will be remembered, along with that of other electronic pioneers. “We have examples of every major contributor to the evolution of radio and TV communications,” said Merriam, tracing the development of wireless starting from the very beginning. A visit would be well worth the reader’s time.

“The wireless collection is only part of the museum’s historical mission,” added Merriam recently. “Rhode Island is known as a pioneer in industrial development, much of which was powered by steam. Our collection of steam engines, which includes one manufactured by Providence’s George H. Corliss, is regularly fired up to demonstrate how such engines energized the many diverse businesses that drove the Ocean State’s economic growth.” Thanks to Bob Merriam and his team of committed volunteers, these unique treasures will remain to educate and enthrall future generations.

[Banner Image: Walter Massie at his Cranston Workshop in the 1930’s (New England Wireless and Steam Museum)]

Bibliography

Oral Interviews of Robert Merriam, Director, Wireless and Steam Museum, East Greenwich, Rhode Island, by Brian L. Wallin, January 10 and August 19, 2016

Dilks, John “Earl Abbot’s Massie Cohere,” QST Magazine (December 2013)

“Massie Wireless Co.’s Convincing Exhibition,” Providence Evening News, Nov. 11, 1911

McAdam, Roger Williams, Floating Palaces (Providence: Mobray Co., 1972)

“Massie System of Wireless Telegraphy,” Electrical World & Engineer, Vol. XLVI, #5 (July 29, 1905)

“Merging the Wireless Companies,” National Magazine (June-July, 1910), pp.425-429

“Wireless on Sound Boats,” Norwalk Hour, May 24, 1904

“Tap,Tap,Tap,” The Block Island Times, May 18, 2013

“Coherer,” at www.en.wikipedia.org

“Massie Wireless Station”, at http://www.rhodeislandradio.org/massie.shtml

“Point Judith Wireless Station,” at www.focus.nps.gov/pdfhost/docs/nrhp/text/01001157.pdf

Information at www.newsm.org/Wireless/Massie.html