In the early morning hours of October 19, 1864, a large Confederate force under the command of Jubal Early attacked a Union encampment near Cedar Creek, Virginia. Stunned from the early morning attack, thousands of half-awake, panicked Union soldiers ran for their lives to escape the Rebel onslaught. The day would have been a total route for the Union army if not for the remarkable stand of two Rhode Island batteries and the Old Vermont Brigade. Battery C and Battery G of the First Rhode Island Light Artillery, together with the Vermonters, held on long enough for the rest of the Union Army of the Shenandoah to reform on the high ground north of Middletown, Virginia. From that position, the Union forces counterattacked in the afternoon, routing their enemy and destroying the remaining Rebel forces in the Shenandoah Valley.[1]

The stand of Battery G at Cedar Creek received praise from all who witnessed it. Colonel Charles H. Tompkins, the regimental commander who was wounded in the battle helping to withdraw Battery G wrote, “The conduct of officers and men was gallant in the extreme and it merits the hearty commendation of all who witnessed it. Rhode Island has just cause to be proud of such soldiers.” General Frank Wheaton wrote of Captain George W. Adams, the grizzled tough commander who led the men into the fight, “In my opinion, he has few superiors in the service, and his admirable battery has been so skillfully and gallantly handled in battle. I never saw a battery more ably and desperately fought.” The battery made a heroic stand, but paid with a heavy price: nine men died, twenty were wounded, and three were captured. Nearly a third of the men in Battery G went down in the fighting at Cedar Creek.[2]

After the battle, Battery C and Battery G were consolidated into one unit, named Battery G. The command returned to the siege lines at Petersburg, Virginia, where on April 2, 1865, Captain Adams led a band of his men on foot as part of a general assault on the Confederate entrenchments. They managed to capture two Confederate cannon which were promptly turned on their former owners. For their part in the attack, seven Rhode Islanders were awarded the Medal of Honor.[3]

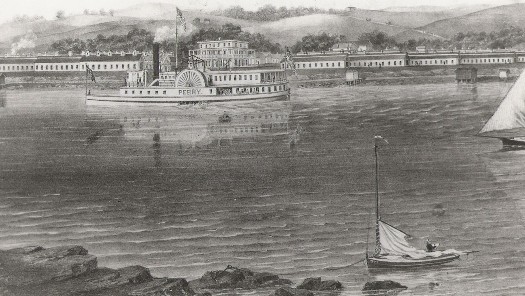

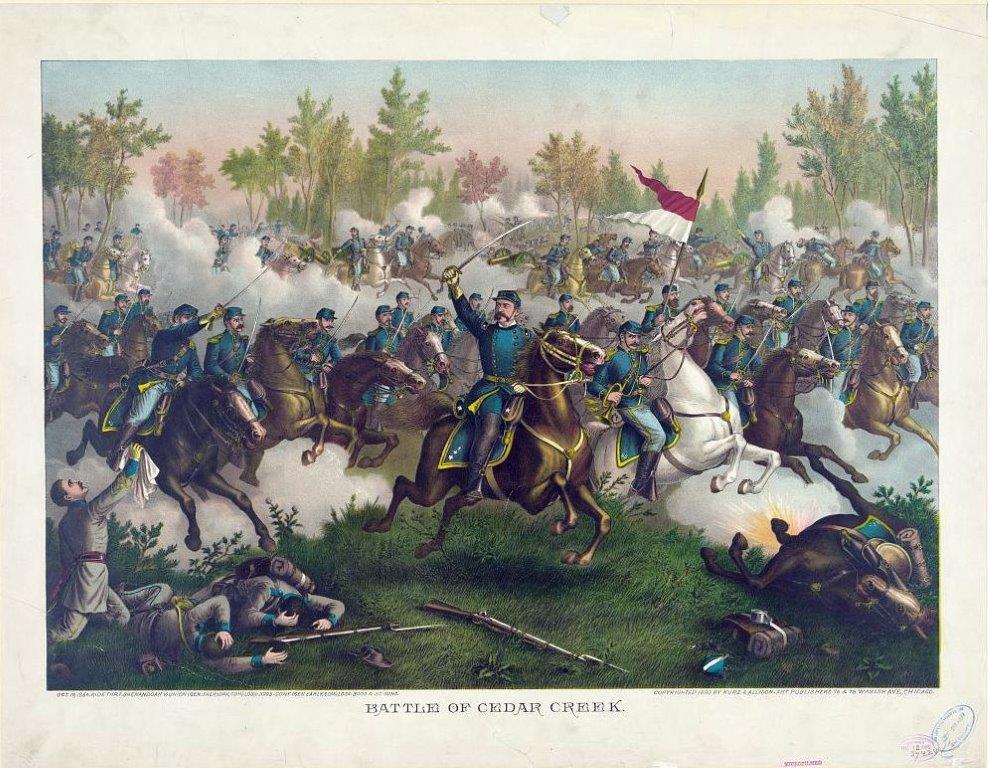

The Battle of Cedar Creek in 1864 in the Shenandoah Valley, Virginia. The battle started badly for Union forces, but ended up in an overwhelming victory (Kurz & Allen)

In 2009, McFarland published my book, The Boys of Adams’ Battery G: The Civil War through the Eyes of a Union Light Artillery Unit. It was the first published account of Battery G, First Rhode Island Light Artillery in the Civil War. Three others, including Captain Adams, historian and veteran of both World Wars General Harold Barker, and television reporter Glenn Laxton, had attempted to write a history, but never completed the task. Because no prior history of the unit had been published, I based nearly my entire narrative on primary manuscript sources. The official papers of the battery from the Rhode Island State Archives proved a blessing, as did the journals and letters of men such as James Barber from Brown University, Albert Cordner’s papers at the North Dakota Historical Society, and pension files from the National Archives.

I spent most of my spare time in 2007 and 2008 when I was a National Park Ranger at Harpers Ferry researching the book. My research trips took me to every battlefield that Battery G fought on in Virginia, West Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania. I was blessed to have the National Archives literally in my backyard and made many research trips there, as well as to the United States Army Military History Institute at Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania. During one research trip, I visited Pamplin Historical Park outside Petersburg, Virginia. The park contains a large Civil War museum, as well as the remains of the entrenchments Battery G attacked on April 2, 1865. While touring the museum, I saw a beautiful light artillery bugler’s coat, ornately trimmed in gold and red lace. I could not help but notice the neat little hole in the center of the coat’s chest, the fatal bullet hole that had struck down the owner of the coat. Reading the sign next to the coat, I was flabbergasted to discover it was owned by a member of Battery G, Bugler William Henry Lewis of Providence.[4]

Bugler William Henry Lewis as he appeared in Providence while on veteran furlough in the winter of 1864. The elaborate coat he is wearing was the coat he was wearing when mortally wounded at Cedar Creek. Today, it is at Pamplin Park in Petersburg, Virginia (Connecticut State Library)

I promptly found the park historian who told me about the coat, and how it came into the collection. As if almost in passing, he said that Lewis’ letters were at the Connecticut State Library in Hartford. I knew that I had to get them as soon as possible. A few phone calls and a week later, I had copies of Lewis’ letters written to his mother, Jane. The letters, covering the period from Chancellorsville through Lewis’ death at Cedar Creek, provided a wealth of information about Battery G, as well as the campaigns in which the unit took part. I readily incorporated the Lewis letters into my book on Battery G, but have long felt they deserved to be published on their own. The majority of the letters concern the battles Lewis fought in, the camp life, and his concerns for his mother and brothers. While these letters are interesting, it is the final two letters in the collection that I feel are most important for the modern reader. The letters written to Jane Lewis after the death of her son tell a poignant and oftentimes forgotten aspect of Civil War combat, those the soldiers left behind.

William Henry Lewis was born in New York in 1845. He was the son of William B. Lewis, a mason born in Rhode Island in 1822, and Jane B. Lewis, a native of Scotland. William had three brothers as well. Jane and William B. Lewis had been married in June 1842 in Providence. According to the 1850 census, the Lewis family lived in the Sixth Ward of Providence, together with other laborers, immigrants, and professionals.[5]

William’s childhood was not a pleasant one. In September 1859, Jane filed for divorce in the Supreme Court of Rhode Island, claiming that William B. “has been guilty of continued + habitual drunkenness, and although able so to do hath neglected to provide her and her infant children with necessaries for their subsistence, and had treated her and her children with great cruelty and has been guilty of gross misbehavior + indecency to the petitioner.” Furthermore, Jane wanted to “have the custody, care, and guardianship of the children.” The court granted the petition, and ordered the divorce. Furthermore, the court ordered William B. to be “restrained from intimidating with the said children or their earnings in any manner whatever.” Jane maintained her married name of Lewis. After the divorce, her two sons Theodore and William provided Jane with her only support. Young William Henry obtained employment in in the jewelry industry to support his mother, while still attending school. He listed his occupation as a “student” when he joined the service.[6]

Although from his surviving letters, it appears that William B. and William H. had an estranged relationship, remarkably, on November 5, 1861, the father and son pair went together to the Benefit Street Arsenal, where both men enlisted in Battery G, First Rhode Island Light Artillery. William Henry, at age sixteen, was appointed a corporal in the unit. Several other boyhood friends also joined up, including Henry C. Seamans, a cigar maker who considered himself a “brother” of William Henry.[7]

Battery G was unique. It included a very large contingent of men from South County, another section of men from western Rhode Island towns such as Scituate and Coventry, a contingent of native born Yankees from Providence, together with newly arrived Irish and German immigrants. They all seamlessly blended to work together to man the six guns of the battery.

Battery G left Rhode Island on December 2, 1861. Under the command of nineteen-year-old Captain Charles Owen, the battery was assigned to the Second Corps of the Army of the Potomac. They moved to the Peninsula in April 1862 and were engaged at Yorktown and Fair Oaks. William H. Lewis had enlisted as a non-commissioned officer and was supposed to set the example for the men under his command. During the Battle of Fair Oaks, Lewis, together with some of the men ran away from their guns as the Confederates closed in. On June 9, 1862 Captain Owen stripped Lewis and two sergeants of their stripes, writing. “Men who are qualified for the positions of sergts and corpls are wanted and not those who when danger or a little hard work is ahead deliberately stop and refuse to try.”[8]

Although demoted from his position as a non-commissioned officer, Lewis apparently had some musical ability and was given the position of bugler, one of two in the battery. After his stripes were removed, Lewis sent them back home to his mother in Providence, hoping to earn them again in combat.[9] After Fair Oaks, Battery G spent a miserable month garrisoning a series of fortifications along the Chickahominy River; scores of men came down with typhoid and dysentery. In late June, the Confederates counterattacked and the battery fought in the Seven Days Battles. In September 1862, Battery G was heavily engaged at Antietam, fighting along Dunker Church Ridge and near the Bloody Lane. Further combat came in December at Fredericksburg, where many Union troops died.

1863 brought a new year and a change for William Henry Lewis. His father was discharged for disability on February 16, 1863, and returned to Providence. In addition, Captain Owen resigned shortly after Fredericksburg. He was replaced by Horace Bloodgood, who resigned a few months later. On May 2, 1863, shortly before the Battle of Chancellorsville, Captain George W. Adams arrived to take command. A native of Providence, a pre-war member of the Providence Marine Corps of Artillery, a merchant, and a decorated combat veteran, Adams had seen nearly two years of service with Battery B. He earned the respect of the men under his command, and led the battery for the rest of the war. In time Battery G was simply known as “Adams’ Battery.”[10]

On May 3, 1863, the battery was heavily engaged at Mayre’s Heights as part of the Chancellorsville Campaign. The command was sent out early to distract the Confederates as Union forces formed up to storm the hill. In the engagement, Bugler Lewis distinguished himself under fire—after his horse was killed, he joined a gun crew and worked on a cannon during the rest of the battle. Although his unit lost seven dead and twenty wounded, the Union forces managed to take the hill. With the death of Bugler Thomas F. Mars in the action, Lewis became chief bugler of the battery, and also acted as a courier and aide for Captain Adams.

After the battle, William’s father happened to be in camp bringing packages to the men in Battery G from. He was given the task of bringing the body of Second Lieutenant Benjamin E. Kelley, whom Lewis called “one of our best lieuts,” back to Providence. The elder Lewis performed the duty and wrote a detailed letter to the Providence Journal informing the people of Rhode Island about the actions of Battery G in the battle. He wrote of his son’s bravery and gave a list of casualties. Bugler Lewis was mortified to read that his father called himself Lieutenant Lewis in the article, when he was in fact a discharged private. William B. Lewis had promised to make another trip to bring items to the men in Battery G, but he never did, prompting William Henry to write to his mother that his father was “up to his old ways.” Battery G was present, but not engaged at Gettysburg, although the men did fight in a rear-guard action on July 5 near Fairfield, Pennsylvania. In November 1863, the command fought at Mine Run.[11]

Battery G began the spring of 1864 as part of the Sixth Corps of the Army of the Potomac. It took part in the dreadful battles at the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Court House, Cold Harbor, and Petersburg. In July 1864, the battery was sent to the Shenandoah Valley after a surprise Confederate raid on Washington, DC. Battery G distinguished itself at Cool Spring on July 18, providing pinpoint suppressing fire to support Union forces attacking a Confederate position. In September, the battery fought well at Opequon and Fisher’s Hill.

After so much marching, campaigning, and combat up and down the Shenandoah Valley, the army rested along the banks of Cedar Creek, south of Middletown, Virginia. That rest was disturbed in the early hours of October 19, when the Confederates made a surprise attack. In the ensuing battle, Bugler William Henry Lewis did not run from combat; he was a courageous veteran fighter now. But he made the ultimate sacrifice, giving his life to save one of the cannon of Battery G from being captured.[12]

The letters below are transcribed directly from the originals contained within the Lewis Family Papers at the Connecticut State Library, which has graciously extended permission to publish the letters and images contained within this article.

Letter I. Henry Chase Seamans was a private in Battery G and was Lewis’s best friend in the service. Bugler Lewis died of his wounds on October 21, 1864, at a field hospital outside of Middletown, Virginia. Private Seamans was especially pained by the death of Lewis, whom he considered his brother. His older biological brother, Frank Seamans had died in Providence on October 11, 1863, of illness contracted in the service, three months after returning home from a nine-month enlistment in Company D, Eleventh Rhode Island Volunteers. Seamans wrote the following letter to Jane Lewis in pencil to inform her that her son had died.

Camp near Middletown Virginia Oct 21st

Mrs. Lewis

With regret I am called to inform you of son William Lewis. He died this morning at half past ten from the effects of his wounds, he was wounded on the 19th. The ball passed through his left side and came out of his right side just below the short rib.[13] I and Edwin Henshaw [14] & a man named Braman [15] dug his grave & buried him. He is buried in a cemetery belonging to the town above. I & Frank Baker [16] stayed there after we buried him and fixed his grave in as good shape as if he were buried at home. Your son was loved by all who new him, at the time he was wounded he jumped from the horse he was riding and sprang on to the horses that were harnessed to our gun and by so doing he saved the gun from being captured.

All the men that are left out of our Battery feel deeply with you and Mrs. Lewis no heart can tell how bad I feel, the last words he said to me was these tell my Dear Mother if my wound should prove to be fatal that I died an honor to my Mother and my Country. He died happy and said he was willing to go to his God for he said I die a Christian. Billy had one hundred I think 60 dollars due him and you can get all of his Government Bounty by seeing Major Monroe [17] or Paymaster Knight.[18] I would advise you to see them as soon as possible on account of his father for if he heard of it, I think he will try to get the money It was Billys Williams request that his mother should have all of his money & all of his pay that are there in the battery. I will send to you by Edwin Henshaw he will be at home in less than 2 weeks as his time is out in seven days.

I have written you all about your son that I can think of at present. I feel deeply with you all and I know that Billy is happy now for he was a good Christian. This sad letter is from me who will ever be willing to help comfort you.

From C. Seamans [19]

Letter II. A month after the battle, as Battery G returned to Washington, D.C. to consolidate with Battery C, First Rhode Island Light Artillery, obtain new horses and guns, and recuperate from the hard-fought campaign in the Shenandoah Valley, Henry Seamans had time to write another letter to Jane Lewis, in response to one she wrote to him.

Camp Russell Va November 30, ‘64

Mrs. Lewis.

Your long looked for letter reached me this morning. I was and have been anxious to hear from you. It seems so lonsome without Billy to talk with. We were as you say the same as Brothers together. He was a good soldier and a brave one and he will never be forgotten in our Battery. Every day there is some one talking about him. Well it was Gods will that he should die and if we are good on this earth we shall surely meet him in Heaven for Billy was a good Christian. You ask me how much money he had coming to him. He had three hundred and fifty dollars coming to him from the Government acct was his bounty money & he had three months pay coming to him and the whole amount that is due him as near as I think is between three hundred & ninety dollars & four hundred dollars. [20] I went to my Captain [21] and asked him about his clothing, and he said they would have to be sent some in a military form what he meant by that I cant make out. You say that you have not been able to do anything since your sons death. Don’t I pray you feel to bad about it we have all die some time. God would not took your son from this wicked world if he had not thought best Billy is far more happier ware he is now than he would be in this world and at Gods appointed time we will all see him never to part again. Wont that be a joyous meeting ware war or suffering never comes. I feel so happy to think he was buried so good but it was a hard task for me. You say if you could get his money, you would get his body. His body is not in our lines at present since my last letter to you the army has fallen back about six miles, so you see it would be impossible to get to it at present and I think it would only be a bill of expense to you. If you should come out to get him for his is buried just as well as if he were at home and with as respect. His grave is besides one that has been there for nearly fifty years. I don’t see what delayed my first letter so long. I hope this letter will reach you in due season and also find you all in good health and spirits. Tell Eddie I will write to him soon, my respects to all of you. Tell George & Theodore [22] I should like to hear from them by mail. There is no news at present. The Army is settled for the winter and the Soldiers are building log houses. I have got my hut finished myself and Frank Baker live together and we are comfortable. We are comfortable as can be, we got plenty to eat and plenty to wear at present. The weather is warm, but we have had some very cold weather and some snow. Well I will close by saying that I shall ever be glad to have you write to me. I will close by subscribing myself your friend.

Henry C. Seamans

Please Direct

Battery “G” R I L A

Sixth Corps

Army of the Shenandoah

Washington D.C.

Do I direct my letters right

H.C.S.

Letter III. Memorial poetry was typically written by the family of Civil War soldiers who died in the service as a means to remember their service. Some of these poems were printed in local newspapers, while broadsides were made of others for distribution to family and friends. This poem, memorializing William H. Lewis, was written by Irene P. Williams.

William H. Lewis Buglar

Wounded Oct. 19 Died the 21st

Aged 19 years.

But Jesus has called the loved one away,

A son, has gone to rest:

Far from this earth where death holds away

He dwells among the blest.

I speak of one who left this state

When his country’s voice come;

How sad, and mournful was his fate

He died far, far, from home.

While nobly fighting on the field,

A deadly missile from the foe

Pierced through his sides, there was nothing to shield

The tiding to his home brought woe.

No Mothers smile from day to day,

Brightened the weary hour;

In vain was human skill to stay

Deaths unrelenting power.

When far from home and those he loved

What must his thoughts have been,

Perchance with fancys eyes he roved

In the streets at home again.

Lord Jesus called him hence from earth

Then wherefore will ye mourn;

His souls to God who gave it birth

Has gone to an eternal home.

Fond Mother, look beyond the grave

Your sons is now in heaven,

Eternal life he there will have

By God’s own hand tis given.

Rest loved one rest, though here on earth

Mother, and brothers, mourn thy loss

From scenes of war you’re gone we trust,

Where gold is never mixes with dross

Nov. 19th 1864, Providence

Irene P. Williams.

Despite the hard work that Henry Seamans and his comrades performed to give William H. Lewis a proper burial spot, he would not rest in the town cemetery in Middletown, Virginia forever. Heeding Seamans’s letter, Jane Lewis never returned her son’s body to Providence. Beginning in 1865, the Federal government began to remove the remains of Union soldiers who died in the northern Shenandoah Valley to the new Winchester National Cemetery, which was dedicated on April 8, 1866. Here, in Grave 3589, William Henry Lewis rests near four other Battery G soldiers who died in the early morning fight for the guns at Cedar Creek. After the war, many other states, including Vermont, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire, dedicated monuments at Winchester National Cemetery to commemorate the valor of their sons who fought in the Shenandoah Valley. A monument was never dedicated to the Rhode Islanders who fought and died in the Shenandoah.[23]

The grave of Bugler William H. Lewis at Winchester National Cemetery, Winchester, Virginia (the Author)

Following Seamans’s advice, Jane Lewis began the process of obtaining a mother’s pension. She filed on November 22, 1864, in Providence, claiming she had been divorced since 1859. Lewis attested in the third person, “She declares that her said son, upon whom she was wholly or in part dependent for support, having left no widow or minor children under sixteen years.” She claimed that William had supported her after the divorce, and had sent the majority of his pay back to Providence to support his mother and brothers. Two neighbors supported these facts.[24]

In addition to the support of her neighbors, Jane turned to the two men who knew her son the most and could attest best to the fact that William Henry supported his mother during his Civil War service:

State of Rhode Island

City and County of Providence

On the 28th day of December 1865 personally appeared before me a Public Notary within + for the County and State aforesaid Frank B. Baker residency of No. 26 “A” Street in this city of Providence and Henry C. Seamans of No. 148 Carpenter Street in said City persons whom I certify to be respectable and entitled to credit who being by me duly sword according to law say that they well knew Jane B. Lewis of said city applicant for pension. That they have known her for the past five years that she is the widow of William B. Lewis who is in such a situation that she cannot enforce her legal claim upon him for subsistence by reason of having divorced from him, and the Mother of William Henry Lewis who entered the military service of the United States and died in such service. That they well knew said William Henry Lewis in his life time that he left no wife or child surviving him and that he contributed to the support of his said mother out of his earnings. That he was employed in the jewelry manufacturing business. The weekly wages of five dollars before entering the military service aforesaid and that said Wm. Henry Lewis has repeatedly told said deponents that he gave all up his said wages to his mother. That said William after he entered the military service aforesaid repeatedly sent his said mother portions of his pay both by express and also through the state allotment commissioner. That we were members of the same Battery “G” 1st Regt R.I. Light Artillery Vols and were quite intimate with the said William Henry Lewis and we have seen letters which he received from his said Mother in which she acknowledged the receipt of the money which the said William sent to her and he repeatedly told us while in the military service aforesaid that he helped support his Mother. Also, that the said Jane B. Lewis had no property and her present means of support is keeping boarders. That deponents as aforesaid have no interest in the prosecution of this claim.

Frank B. Baker

Henry C. Seamans [25]

Unlike many other soldiers, widows, orphans, and mothers, Jane Lewis did not have relatively long to wait in obtaining her first pension check. She began to be paid eight dollars per month, beginning on February 9, 1866, with back pay to October 22, 1864, the day after William died. In 1871, the name “W.H. Lewis” was inscribed on the Soldiers and Sailors Monument in Providence, listing the young man as an official Civil War casualty from Rhode Island. Jane’s divorced husband, William B. Lewis, died in Cranston on December 7, 1882. He was buried in the Grand Army of the Republic Lot in North Burial Ground in Providence. By the time she died in Providence on March 18, 1908, Jane was receiving twelve dollars per month. It was small compensation in memory of her beloved son William who died forty-two years earlier saving a gun from capture at Cedar Creek.[26]

[Banner image: The Battle of Cedar Creek in 1864 in the Shenandoah Valley, Virginia. The battle started badly for Union forces, but ended up in an overwhelming victory (Kurz & Allen)]

Notes:

[1] Diary of James A. Barber, October 19, 1864, John Hay Library, Brown University. Howard Coffin, Full Duty: Vermonters in the Civil War. (Woodstock, VT: Countryman Press, 1993), 306-318. [2] John Russell Bartlett, ed., Memoirs of Rhode Island Officers Who Were Engaged in the Service of Their Country During the Great Rebellion of the South: Illustrated with Thirty-Four Portraits. (Providence: S.S. Rider & Brother, 1867), 415-417; Muster Rolls and Descriptive Book of Battery G, First Rhode Island Light Artillery, Rhode Island State Archives. [3] Walter F. Beyer and Oscar F. Keydel, Deeds of Valor: How America’s Heroes won the Medal of Honor. (Detroit: Perrien-Keydel Co., 1901), 515-516. [4] The coat of Bugler William Henry Lewis can be seen on page 228 of Don Troiani, Earl J. Coates, and Michael J. McAfee, Don Troiani’s Regiments & Uniforms of the Civil War (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2002). [5] 1850 U.S. Census, County of Providence, City of Providence, Ward 6, National Archives, Washington, DC; Jane B. Lewis, Divorce Petition, William H. Lewis Pension File, National Archives. [5] Affidavits of Elizabeth B. Seymour and Theodore S. Seymour, Lewis Pension File; Affidavit of Henry C. Seamans and Frank B. Baker, December 28, 1864, Lewis Pension File; Battery G Descriptive Book. [6] Revised Register of Rhode Island Volunteers: Volume II (Providence: E.L. Freeman, 1893), 918: 922. See the letters of William H. Lewis at the Connecticut State Library for more information on his relationship with William B., especially letters dated May 21, 1863, June 6, 1863, and June 22, 1863. [7] General Orders #8, Battery G, First Rhode Island Light Artillery Orderly Book, First Rhode Island Light Artillery Papers, National Archives. [8] William H. Lewis to Jane B. Lewis, August 8, 1864, Connecticut State Library. [9] For more information on Captain George W. Adams, refer to In Memoriam: George William Adams. (Providence: NP, 1883), copy at Providence Public Library and author’s collection. [10] Providence Journal, May 8, 1863; William H. Lewis to Jane B. Lewis, May 21, 1863 and June 22, 1863, Connecticut State Library. [11] This is a thumbnail sketch of Battery G that is extracted from Robert Grandchamp, The Boys of Adams’ Battery G: The Civil War through the Eyes of a Union Light Artillery Unit (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2009). [12] Obviously, Lewis was not buried wearing the coat he was shot in, as it is now on display at the Pamplin Park Museum near Petersburg, Virginia. [13] Private Edwin B. Henshaw was an eighteen-year-old clerk from Providence who transferred to Battery G from Company D, Second Rhode Island Volunteers, on December 5, 1863. He was mustered out at Middletown, Virginia, on October 31, 1864, and returned to Rhode Island. Revised Register, Volume II, 915; Battery G Descriptive Book. [14] Marcus L. Braman enlisted in Battery G on June 20, 1863; he was listed as a twenty-two-year-old shoemaker who resided in Providence. He was mustered out on June 24, 1865. He died August 26, 1874, and is buried at Old Union Center Cemetery, Union, Connecticut. Revised Register, Volume II, 909; Battery G, Descriptive Book. See also http://www.findagrave.com/cgibin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GSln=braman&GSfn=marcus&GSmn=l&GSbyrel=all&GSdyrel=all&GSob=n&GRid=96902401&df=all& [15] Frank B. Baker was an eighteen-year-old student and a resident of Apponaug, in Warwick, when he enlisted on March 11, 1862. He was mustered out March 11, 1865. Revised Register, Volume II, 908; Battery G, Descriptive Book. [16] Lieutenant Colonel John Albert Monroe of Providence was born in 1836. A student at Brown University when the war broke out, Monroe was a member of the Providence Marine Corps of Artillery. He enlisted as a lieutenant in Battery A, and quickly was promoted to captain of Battery D. Monroe earned praise for his heroism at Second Manassas and Antietam. After these battles he was promoted to major and lieutenant colonel of the First Rhode Island Light Artillery. He commanded an artillery camp of instruction in Washington, D.C., served as an artillery brigade commander, and was mustered out in the fall of 1864. He returned to Providence, and became a civil engineer. Highly active in veterans’ affairs, Monroe died in 1891. Bartlett, ed., Memoirs of Rhode Island Officers, 405-407. [17] Jabez Comstock Knight, 1815-1900, was the paymaster general of the Rhode Island Militia. He was mayor of Providence during the Civil War, encouraging enlistments and industry to support the Union. Welcome Greene Arnold, The Providence Plantations for 250 Years (Providence: J.A. & R.A. R.A. Reid, 1886), 104-105. [18] Henry Chase Seamans enlisted from Providence into Battery G on December 17, 1861; he gave his occupation as a cigar maker and stated he was sixteen-years old. He reenlisted as a veteran volunteer in 1863. Seamans was mustered out on June 24, 1865. He died in Providence on September 3, 1886, and is buried at North Burial Ground. Battery G, Descriptive Book and http://www.findagrave.com/cgibin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GSln=seamans&GSfn=henry+&GSmn=c&GSbyrel=all&GSdyrel=all&GSob=n&GRid=33275223&df=all& [19] In December 1863, William Henry Lewis reenlisted as a veteran volunteer and received a thirty-five-day furlough home, as well as a substantial bounty to serve another enlistment. It was during this furlough back to Providence, accompanied by Seamans, that the only known images of Lewis were taken. William H. Lewis, Service File, National Archives. William H. Lewis, photographs, William H. Lewis Papers, Connecticut State Library. [20] Captain George W. Adams of Providence commanded Battery G. Providence Journal, October 17, 1883. [21] The sons of Jane B. and William B. Lewis. [22] National Cemetery Administration, Winchester National Cemetery, accessed October 29, 2016, http://www.cem.va.gov/CEM/cems/nchp/winchester.asp. [23] Jane B. Lewis, Declaration for Mother’s Pension, November 22, 1864, Lewis Pension File. Seymour Affidavits, Lewis Pension File. [24] Baker and Seamans Affidavit, Lewis Service File. [25] Proceedings at the Dedication of the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument in Providence, To which is Appended a list of the Deceased Soldiers and Sailors whose Names are Sculptured upon the Monument (Providence: A. Crawford Greene, 1871), 62; Burial Records of Prescott Post #1, Grand Army of the Republic Papers, Rhode Island Historical Society; Jane B. Lewis Pension Certificate and Pension Drop Certificate in Lewis Pension File.