With the firing on Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, Rhode Islanders eagerly answered the call to arms. From Westerly to Woonsocket, and from Wallum Lake to Little Compton, the men from Rhode Island went to war. When it was over the smallest state in the Union mustered eight regiments of infantry, three regiments and a squadron of cavalry, three heavy artillery regiments, and ten batteries of light artillery, as well as hundreds of men who served in the United States Navy, Army, and Marine Corps. Rhode Islanders served in nearly every major battle of the war, firing the first infantry shots at Bull Run, and some of the last by the cavalry at Appomattox. Over 23,000 Rhode Islanders enlisted in the Civil War, and over 2,000 gave the ultimate sacrifice. [1]

Among the many books Robert Grandchamp has authored on Rhode Island’s role in the Civil War is the above one.

From 1862 until the second decade of the twentieth century, the soldiers and sailors of Rhode Island also left an indelible mark on the pages of history by writing and publishing histories of their participation in the Civil War. Indeed, with the exception of Batteries C and G, First Rhode Island Light Artillery and the Second and Third Rhode Island Cavalry Regiments, every unit from Rhode Island published a history written by men who served. Over the last century these sources were complemented by scores of other books and articles by scholars, Civil War buffs, and those interested in Rhode Island’s role in the war Indeed, Rhode Island has perhaps the greatest written record of any northern state in the Civil War era.

In 1862, Augustus Woodbury published A Narrative of the Campaign of the First Rhode Island Regiment in the Spring and Summer of 1861. This book was the first published regimental history written by a Civil War participant. Woodbury, who served in the First Rhode Island Detached Militia as the regimental chaplain, set the standard by which all future regimental histories would be written. [2] He placed the role of the First Rhode Island within the context of the Bull Run Campaign and focused on the participation of the regiment in the engagement. Woodbury provided a complete roster of the First Rhode Island that included short biographies of the officers and men who perished in the service. Woodbury also listed men from the regiment who reenlisted in other units during the war.

In 1864, Edwin W. Stone, who served in Battery C, First Rhode Island Light Artillery, published Rhode Island in the Rebellion. During the war, Stone served as a correspondent to the Providence Journal, writing detailed letters about his experiences in the Army of the Potomac. The book was published in early 1864, and contains Stone’s letters written through Gettysburg only. Despite this, Rhode Island in the Rebellion is a valuable resource. Nearly a third of book is an appendix with brief histories of each Rhode Island regiment and battery. Stone did not write these histories himself; rather a member of each unit wrote a history for inclusion in the book. These histories present a remarkable view of the war as it was going on by the participants. In addition, Stone also included brief biographies of several Rhode Island soldiers who died in the war. Rhode Island in the Rebellion was reissued in 1865 with the inclusion of a chapter about the events of 1864 and additional biographical material about officers who died in the 1864 campaigns. Often overlooked today, Rhode Island in the Rebellion remains a valuable resource. [3]

Chaplain Woodbury returned to publishing in 1875, writing the official regimental history of the Second Rhode Island Volunteers. To accomplish his work, Woodbury spoke with fellow veterans of the regiment and was given access to both private and personal papers of the soldiers of the Second. The Providence Journal reported: “The historian understood that nothing but the truth and impartiality was sought, and from such a man nothing else could have been obtained, even desired. The narrative is sprightly and told in Mr. Woodbury’s happiest style.”

Chaplain Frederic Denison, who served in both the First Rhode Island Cavalry and the Third Rhode Island Heavy Artillery, published Sabres and Spurs and Shot and Shell in 1876 and 1879, respectively. Denison, a Brown University educated Baptist minister, was also a historian who wrote two excellent histories that are still widely considered to be two of the best sources about the cavalry in the Army of the Potomac and service in South Carolina. A poet as well, Denison published his poetry in these volumes. [4]

One of the most important sources published by Rhode Islanders was the one hundred papers published in the ten volumes of the Personal Narratives of Events in the War of the Rebellion: Being papers read before the Rhode Island Soldiers and Sailors Historical Society. Formed in Providence in 1874, the Soldiers and Sailors Historical Society comprised veterans who met each month when one of the members would present a historical paper on his military service. One hundred of these papers were issued in paperback form from 1878 until 1915, shortly after which the society disbanded. The New England Historical and Genealogical Register recorded: “The society deserves much credit for its labors in preserving the record of events in so important a portion of our national history.” [5]

The papers were collected and published in hardcover in volumes of ten papers each, making up ten full volumes. Publishing the single volumes received praise: “They contain much interesting matter concerning events in the late war for the preservation of the union, which but for this mode of publication would have been lost.” Not all papers read before the Society were published, however; many exist in manuscript form at the Rhode Island Historical Society and the Providence Public Library. Others were independently published elsewhere by their authors.

In 1890, the veterans of the Fifth Rhode Island Heavy Artillery sent a resolution to the Rhode Island General Assembly asking for money to help in writing and publishing a regimental history. Before 1892, Rhode Islanders had sporadically published pieces about their participation in the war. These histories were typically published by and paid for entirely by the veterans or their regimental associations. Often published in limited numbers, these books were found in the many mill village libraries throughout the state.

Beginning in 1892, the Rhode Island General Assembly offered all Rhode Island regimental veteran associations six hundred dollars to publish regimental histories of their units. The state ultimately purchased two hundred copies of each history “for the use of the state,” often sending them to libraries both in Rhode Island and elsewhere, as well as to veteran’s homes and Grand Army of the Republic Posts around the country. In addition, members of the General Assembly and judges of the Rhode Island court system were also given copies to give to their constituents. The generous gift of the Rhode Island General Assembly was the catalyst for the remaining Rhode Island veteran associations to publish regimental histories. [6]

Typical of these histories is the massive 1903 regimental history of the Seventh Rhode Island Volunteers. Raised in 1862, the Seventh saw hard service in both the Army of the Potomac and in Mississippi during the Vicksburg Campaign. The soldiers of the Seventh formed a veteran association in 1873 but did not begin to seriously consider writing a regimental history until 1889 when a committee of twenty-five veterans gathered to write the history. But with so many cooks, little was done. “A committee of so many members was found to be unwieldy and inefficient and accomplished little of importance,” wrote one member of the regiment. In 1893, the Seventh Rhode Island Veteran Association’s president, Nathan B. Lewis, who had served in the regiment as a corporal and was then a prominent lawyer and judge in Washington County, appointed another committee of five members to gather funds to publish the history to supplement the money provided by the state. William P. Hopkins, a former drummer in the regiment, was appointed to write the actual history.

Hopkins, then living in Lawrence, Massachusetts, was “indefatigable in collecting material for such a work.” He wrote thousands of letters to fellow veterans, including Confederates whom the Seventh fought against. He also gathered letters and diaries of fellow veterans from the Seventh, collected hundreds of photographs of regimental comrades, and wrote biographical sketches of most of the soldiers in the regiment. Furthermore, Hopkins traveled throughout the South, revisiting the battlefields where the Seventh had fought and camped in Maryland, Virginia, and Mississippi. By the time he finished his research, which took up most of the 1890s, Hopkins “had sufficient material to make a credible history of the regiment.”

After writing his history of the Seventh Rhode Island, Hopkins had it edited by Dr. George B. Peck of Providence, himself a veteran of the Second Rhode Island and author of several accounts of his own service. Hopkins wrote, “The result sought in the publication of this volume is to place on record an authentic account of the part performed by the Seventh Rhode Island Regiment in the suppression of the Rebellion and to perpetuate the memory of the heroic men who gave up their lives in the service of their country.” When it was published in 1903, The Seventh Regiment Rhode Island Volunteers in the Civil War, 1862-1865 was widely hailed. It is still one of the finest regimental histories published in the postwar period. Filled with hundreds of photographs and biographical sketches, and, with a main text that reads like a diary from a front-line participant, it is one of the greatest books ever published about Rhode Island in the Civil War era. [7]

The First Rhode Island Light Artillery regiment was unique in its service. Recruited at the Benefit Street Arsenal in Providence, the eight batteries of the regiment were mustered in one battery at a time and never served together as a full regiment. One veteran jokingly referred to the First Rhode Island Light Artillery as a “geography class” because of its varied service. In July 1863, Batteries A, B, C, E, and G were serving in the Army of the Potomac at Gettysburg; Battery D was stationed in Kentucky with the Ninth Corps; Battery F was detailed to New Bern, North Carolina; and Battery H served in the defenses of Washington, D.C. Because of the wide and varied service of these batteries, each unit was authorized to publish its own history; all did with the exception of Battery C and Battery G. [8]

Lieutenant Colonel Welcome B. Sayles of Providence was a prominent Democratic politician who ran the Providence Press, the organ of the Rhode Island Democratic Party. He had been a strong supporter of Thomas Wilson Dorr in 1842. At Fredericksburg, he was killed early in the fight as he was hit directly by a shell that eviscerated him

Taken together, these regimental histories form one of the most important resources for the study of Rhode Island in the Civil War period. Written by the men who participated in the units, they present a detailed, first-hand account of their service. Furthermore, many of the volumes contain engravings or photographs of the officers and men who served. Of particular importance are biographical sketches and accounts of the actions in which they participated.

It must be kept in mind that the postwar histories did not always include the seamy side of war. Often they do not discuss desertions, the high bounties that some men enlisted for, and drunk or incompetent officers. For the most part, however, they provide an honest, day-to-day view of Rhode Island’s Civil War units. The books were widely distributed and varied in cost. For example, the history of Battery B sold for three dollars, while the history of the Seventh Rhode Island Volunteers originally sold for five dollars. The men who wrote these books often spent more on their publications than what they earned in sales. It was a labor of love that led them to recall proudly their unit’s part in the Civil War. [9]

After 1917, with the disbandment of the Rhode Island Soldiers and Sailors Historical Society and the passing of many of the state’s Civil War veterans, the steady stream of publications about Rhode Island and the Civil War began to decline. In 1964, Brigadier General Harold R. Barker, a veteran of both world wars whose grandfather had served in the First Rhode Island Detached Militia, wrote History of Rhode Island Combat Units in the Civil War, which served as the official state history to commemorate the Centennial of the Civil War. General Barker’s book is a compression of the regimental histories published by the veterans after the war. He performed no original research and instead published excerpts from the histories to detail the role of a Rhode Island unit in a particular battle. The book is heavily illustrated and includes details such as Medal of Honor recipients and the battle honors earned by each regiment. Widely distributed by the state, General Barker’s book is still frequently read and is often the first book about Rhode Island and the Civil War that many read . [10]

It was not until the 1980s that another round of books about Rhode Island and the Civil War were published. In 1985, Robert Hunt Rhodes, the great-grandson of Colonel Elisha Hunt Rhodes of the Second Rhode Island Volunteers, published his ancestor’s diary through Mowbray Publishing in Woonsocket as All for the Union. This book is a publication of the fair copy of Rhodes’s diary, recopied after the war, and differs in some places from his field journal, especially in his opinions of the Union high command. The book was not widely known until Rhodes’s neighbor in New Hampshire, Ken Burns, bought a copy. Burns used Elisha Hunt Rhodes as the archetypical Union soldier in his 1990 television series The Civil War. All for the Union was republished in paperback by Random House, selling tens of thousands of copies and becoming the most widely read book about Rhode Island and the Civil War.

In the early 1990s, Kris VanDenBossche, an antiques dealer from Hopkinton, formed the Rhode Island Historical Document Transcription Project. He traveled the state seeking documents and photographs for inclusion in a project sponsored by the Rhode Island Council of the Humanities. VanDenBossche gathered hundreds of letters and transcribed them for publication. His book, Pleas Excuse All Bad Writing, was distributed to every library in Rhode Island and not made available for sale to the general public. A companion volume, Write Soon and Give Me All the News, is found at the Rhode Island Historical Society. These books are two of the best and most available sources of letters written by Rhode Island soldiers. [11]

In 1996 Butternut & Blue, a Maryland based publisher of Civil War books, reissued the histories of the First Rhode Island Cavalry and Battery B, and the First Rhode Island Light Artillery, as part of their Army of the Potomac Series. These two republications featured an extensive introduction about both units written by Robert Durwood Madison, a native Rhode Islander and then professor of history at the United States Naval Academy.

With the advent of newer, less expensive publishing technologies, companies such as Higginson Books in Salem, Massachusetts, began to reissue reprints of regimental histories. Previously available only at libraries or for hefty sums from rare book dealers, these reprints made the regimental histories available to the public again. With the emergence of a renewed interest in the Civil War beginning in the late 1980s and the founding of the Rhode Island Civil War Round Table, reenacting groups such as Battery B and the Second Rhode Island along with a surge of membership in the Rhode Island Sons of Union Veterans, a renewed interest in the history of Rhode Island and the Civil War.

Perhaps the greatest contribution to the historiography of Rhode Island and the Civil War era in modern times has been made by Robert Grandchamp (the author of this article). A twelfth generation Rhode Islander, Grandchamp, discovered at an early age that his third great uncle, Alfred Sheldon Knight, had served and died in the service as a member of Company C, Seventh Rhode Island Volunteers. Inspired by his ancestor’s service and sacrifice, in high school he took an active interest in the overall history of Rhode Island and the Civil War. This interest eventually took him to Rhode Island College, where he earned an M.A. in American history.

Grandchamp believed firmly in conducting in-depth, primary research by visiting every historical society, archive, and library in the state, and visiting nearly every Civil War era graveyard in Rhode Island. Furthermore, he has traveled the country, visiting museums, libraries, and battlefields gathering material from out-of-state sources on Rhode Island’s participation. Grandchamp’s interest also expanded to Rhode Island’s role in World War I. In addition, he actively collected, and continues to collect, books, artifacts, and manuscript material about Rhode Island military history.

After twenty years of research, Grandchamp has come to be widely considered as the nation’s foremost authority on Rhode Island military history. He is often consulted by the Rhode Island National Guard, the Varnum Continentals, Kentish Guards, and other organizations for his expertise in military history. During his college years, from 2008-2011 he was the lead researcher and writer of a history of the Providence Marine Corps of Artillery and the 103rd Field Artillery of the Rhode Island National Guard. Grandchamp served as a National Park Ranger at Harpers Ferry and Shenandoah. This experience led to many contacts in the historical community that can be tapped as needed. In 2012, Robert researched and led a program as part of Rhode Island Day at Antietam National Battlefield.

Robert’s work has been published in a wide variety of national and local magazines and journals. He is a frequent contributor to Rhode Island Roots, published by the Rhode Island Genealogical Society. Furthermore, in 2017 he published a controversial article in America’s Civil War magazine that established that Sullivan Ballou did not write the famous last letter made famous in Ken Burns’s Civil War series. In addition, he has authored a dozen books for which he received letters of commendation from Governor Lincoln Chaffee and Mayor Angel Tavares of Providence. Furthermore, he became the first civilian recipient of the Order of St. Barbara from the Rhode Island National Guard for his contributions to the history of the Rhode Island artillery community. Among Grandchamp’s writings are regimental histories of the Seventh Rhode Island Volunteers and Battery G, First Rhode Island Light Artillery. He has edited the correspondence of several Rhode Island soldiers, co-authored a bi-centennial history of the Providence Marine Corps of Artillery, and wrote the popular book, Rhode Island and the Civil War: Voices from the Ocean State.

Alfred Sheldon Knight of Scituate was a 29 year old dairy farmer who enlisted in Company C of the Seventh Rhode Island Volunteers in August 1862. He died of pneumonia on January 31, 1863 and is buried in the family cemetery on reservoir property in Scituate

Robert Grandchamp also authored The Seventh Rhode Island Infantry in the Civil War (McFarland, 2014)

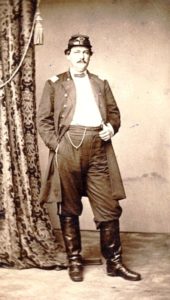

Colonel Zenas Randall Bliss. A native of Johnston, Bliss was an 1854 graduate of West Point. He molded the Seventh Rhode Island into a fine combat regiment. At Fredericksburg he earned the Medal of Honor for his heroism in the fight. After the Civil War, Bliss became an advocate for the Buffalo Soldiers and spent the rest of his career commanding them. Bliss served forty-five years in the Army and retired a major general. He died in 1900 and is buried at Arlington (Robert Grandchamp Collection)

In addition to Robert Grandchamp’s work, the Sesquicentennial of the Civil War, commemorated from 2011-2015, also saw several other publications. Although widely known as a foremost Lincoln scholar, Judge Frank Williams, the chair of the state committee for the Sesquicentennial, edited a book about the contributions of those Rhode Islanders who remained at home during the war. Frank Grzyb, a Vietnam veteran and retired government employee, wrote two books, Hidden History of Rhode Island and the Civil War, and Rhode Island’s Civil War Hospital: Life and Death at Portsmouth Grove. Most recently, the East Providence Historical Society released All Quiet on the Rappahannock Tonight, a compilation of the letters of Lieutenant Peter Hunt of Battery A who was mortally wounded at Cold Harbor.

Unfortunately, the future does not appear bright for continued publications about Rhode Island and the Civil War. While the veterans who took part in the conflict wanted their stories told and were often published by the Soldiers and Sailors Historical Society, or in state-sponsored regimental histories. Current scholarship in the field is limited to two active participants, while academia often does not view the study of Civil War military history in the best light.

The Civil War Sesquicentennial commemorated from 2011-2015 was a litmus test for Rhode Island in which the state failed. While other states such as Virginia, South Carolina, Maine, and, notably, Connecticut, supported and funded commissions to organize events and publications, Rhode Island only organized a group in February 2011. Led by noted Lincoln scholar and retired state Chief Justice Frank Williams, the twenty-seven-member commission, composed of Rhode Islanders from a wide array of backgrounds, published a lofty mission statement:

“The Commission and its advisory council will explore and publicize this important history – military, political, and cultural – in a myriad of ways during the years 2011 through 2015. We will support projects to restore Civil War monuments and to digitize Civil War related data; we will endorse reenactments and exhibits, expand this website, and produce publications; and we will devote much energy to the education of our citizens – especially students – about this crucial era of our history. The volunteer efforts of the Commission, its advisory council, supportive educators, and Rhode Island citizens in general – all without remuneration – will strive to meet these goals.”

Unfortunately, few, if any of these goals were met. While a website was created by the commission and did include some images of Rhode Island soldiers, and some events were listed, the website did not accomplish much, in comparison to neighboring Connecticut which frequently updated with events taking place all through the Nutmeg State. The twenty-seven-member committee proved to be unwieldly, while the Rhode Island General Assembly did not fund the commission’s work; instead they had to rely on donations to remain active. The small size of Rhode Island once again resulted in low funding of the state’s history.

In April 2011, a group of Rhode Islanders met at the Benefit Street Arsenal to commemorate 150 years since the Providence Marine Corps of Artillery left the building as one of the first groups of northern militia to respond to Lincoln’s call for volunteers. Four years later, in April 2015, another ceremony was held at the arsenal to commemorate the end of the war and to dedicate a plaque to the seven soldiers of Battery G who earned the Medal of Honor at Petersburg on April 2, 1865. With the exception of the annual Fort Adams reenactment, and Rhode Island Day at Antietam National Battlefield, neither event being sponsored by the Civil War Sesquicentennial commission, few events occurred in Rhode Island during the sesquicentennial.

While Connecticut sponsored an official sesquicentennial history of its participation, Rhode Island did not. Rather, the Rhode Island Sesquicentennial Commission secured a small grant to publish The Rhode Island Homefront in the Civil War Era, a compilation of essays regarding economic, social, and political events in Rhode Island. Sam Simons published a well-received series of bi-weekly articles in The Westerly Sun from 2012-2013, but even these were read only locally in part of South County. A planned one-day symposium in April 2014 was canceled due to lack of preregistration. Unfortunately, in the end, the Civil War Sesquicentennial was a failure in Rhode Island and did not generate the interest in the conflict that was created in other states.

Why is the Civil War often placed on the back burner in Rhode Island? In Maine, one can walk into the stately home of war hero General Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain; in Connecticut one can visit the restored Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) Hall in Rockville, now home to the New England Civil War Museum. Lebanon, New Hampshire, also boasts a restored GAR Hall, while a visitor can drive to many historical sites in Vermont, including the American Precision Museum in Windsor, originally a musket manufacturing center. In Rhode Island, with the exception of Fort Adams and the Westerly Public Library, once a GAR Hall, few, if any tangible sites remain in Rhode Island relating to the Civil War. Furthermore, much of the state’s vast history is stored in archival boxes at Brown University, the Rhode Island Historical Society, and the Rhode Island State Archives. With the exception of the magnificent Varnum Continentals collection in East Greenwich, there is not a major museum in the state dedicated to Rhode Island’s rich military history.

There are several major reasons why Rhode Island Civil War history is not front and center. First, Rhode Island does not have a statewide history museum to tell the story of its past. The proposed Heritage Harbor Museum in Providence never came to fruition. Local historical societies, while meaning well, often lack trained personnel and resources. In addition, there is not a dedicated facility to host the rich and vast state archives. Rather, the archives are held in a cluttered, risk prone building in the middle of downtown Providence, instead of in a dedicated facility as in every other New England state.

Rhode Island is very much a community of continued immigration from around the world. As each new ethnic group comes into Rhode Island, it does not look to the deeds of the past. The Irish and Quebecois were active participants in the Civil War experience in Rhode Island; however, they were supplemented by the Italians, and in turn by Latinos and East Asians. Each new group, while bringing much and contributing to the vitality of Rhode Island, has not embraced the rich historical past of Rhode Island. One only needs to look at the Soldiers and Sailors Monument in Providence to understand this. The monument is frequently covered in pigeon excrement, while vagabonds sleep, and transients sit wild-eyed on this sacred place to commemorate Rhode Islanders who gave “the last full measure of devotion.”

In addition, Rhode Island history is not, for the most part, an academic discipline. With the retirement of Patrick Conley from Providence College, and Stanley Lemons from Rhode Island College, the state lost two of the best academics in the field of Rhode Island history who were not replaced with equal peers. Another bright light was lost in 2017 when Albert Klyberg, former head of the Rhode Island Historical Society, and one of the foremost champions of the state’s history, died. While Rhode Island College, the University of Rhode Island, Roger Williams University, and others teach Rhode Island history classes, they are general survey courses, not in-depth studies.

Also inhibiting the study of the state’s history is the lack of an academic press attached to a university or college in Rhode Island publishing books about the rich history of the state. When academics do study Rhode Island history it is largely the colonial period, or Rhode Island’s notorious involvement in the Triangle Trade. Even the Fourteenth Rhode Island Heavy Artillery, a black regiment, has not received the academic treatment of the neighboring Fifty-Fourth Massachusetts. A lack of education about Rhode Island history, coupled with a disregard of the state’s history have all contributed to Rhode Island Civil War history’s being neglected.

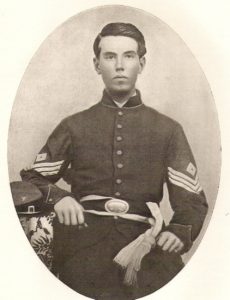

First Sergeant Charles H. Kellen of Providence served in Company F. Mortally wounded at Fredericksburg, he was posthumously promoted to second lieutenant for heroism on the field ((Robert Grandchamp Collection)

In conclusion, the history of Rhode Island and the Civil War must continue to be studied. The Civil War was and remains the defining moment in American history. Rhode Islanders left an indelible mark on the battlefield and in the pages of the histories they wrote. It waits to be seen if future generations will continue writing about the noble deeds they achieved.

[Banner Image: First Sergeant Charles H. Kellen of Providence served in Company F. Mortally wounded at Fredericksburg, he was posthumously promoted to second lieutenant for heroism on the field ((Robert Grandchamp Collection)]

Notes:

[1] For a good overview of the Rhode Island Civil War experience, refer to Robert Grandchamp, Rhode Island and the Civil War: Voices from the Ocean State (Charleston: History Press, 2012). [2] Newport Mercury, June 21, 1862. [3] Edwin M. Stone, Rhode Island in the Rebellion (Providence: George H. Whitney, 1864 and 1865). [4] Providence Journal, March 17, 1875. Frederic Denison, Sabres and Spurs: The First Regiment Rhode Island Cavalry in the Civil War, 1861-1865. Its Origins, Marches, Scouts, Skirmishes, Raid, Battles, Sufferings, Victories, and Appropriate Official Papers; with The Roll of Honor and Roll of the Regiment (Central Falls: E.L. Freeman, 1876). [5] Finding Aid, Rhode Island Soldiers and Sailors Historical Society Papers, MSS 723, Rhode Island Historical Society, Providence, RI. “Book Notices,” The New England Historical and Genealogical Register, Vol. 36 (1882), 100-101. “Book Notices,” ibid., Vol. 35 (1881), 406. [6] John K. Burlingame, History of the Fifth Regiment of Rhode Island Heavy Artillery During Three Years and a Half of Service in North Carolina. January 1862-June 1865 (Providence: Snow & Farnum, 1892), v-viii. Acts and Resolves Passed by the General Assembly of the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations at the January Session, 1899 (Providence: E.L. Freeman, 1899), 221-222. [7] Seventh Rhode Island Volunteers, Regimental Association Minute Books, 1885-1903, Robert Grandchamp Collection. William P. Hopkins, The Seventh Regiment Rhode Island Volunteers in the Civil War, 1862-1865 (Providence: Snow & Farnum, 1903), i-xvi. [8] George B. Peck, Historical Address Delivered at the Dedication of the Memorial Tablet on the Arsenal Benefit Street, Corner of Meeting Providence, R.I. Thursday July 19, 1917 (Providence: Rhode Island Print Co., 1917), 5-15. [9] Advertisement for Battery B, First Rhode Island Light Artillery Regimental History, Gettysburg National Military Park, Gettysburg, PA, Publisher’s Weekly, April 4, 1903. Providence Evening Press, July 21, 1871. [10] Harold R. Barker, History of the Rhode Island Combat Units in the Civil War (1861-1865) (Providence: NP, 1964). Harold R. Barker Papers, Rhode Island Historical Society and Benefit Street Arsenal, Providence, RI. [11] Standard Times, April 8, 1992. Westerly Sun, May 23, 1993. Westerly Sun, August 2, 1992.