Firstly, I must confess that math is not my biggest strength. As a student at Coventry High School in the early 2000s, I sat through countless hours of algebra and geometry, and still to this day cannot figure out how x2 +y2=z2! However, as a Civil War historian, numbers fascinate me. Casualty figures, bounty money paid out, numbers of men engaged in a particular battle, these are all statistics that I use to build my narratives as a historian. It is real life math that I actually use in my daily life that I find fascinating. Finding the area of a trapezoid? After twenty years I cannot even remember what a trapezoid is!

When it comes to Civil War regiments from Rhode Island, the numbering of those regiments is fascinating. This article will delve into why certain regiments were numbered the way they were and why certain numbers are missing from the sequence of regimental numbers assigned to Rhode Island regiments.

When the Civil War broke out in April 1861, Rhode Island, unlike most states, did not have a statewide regimental militia organization. Rather, the state militia was composed of nearly twenty active companies spread throughout the state. Eight militia units—the Westerly Rifles, Woonsocket Guards, Newport Artillery, Providence Artillery, Mechanics Rifles, First Light Infantry, Pawtucket Light Guard, and the National Cadets—formed together to create the First Rhode Island Detached Militia. The organization was called such because it was a detached organization from the Rhode Island militia that was mustered into Federal service for ninety days.

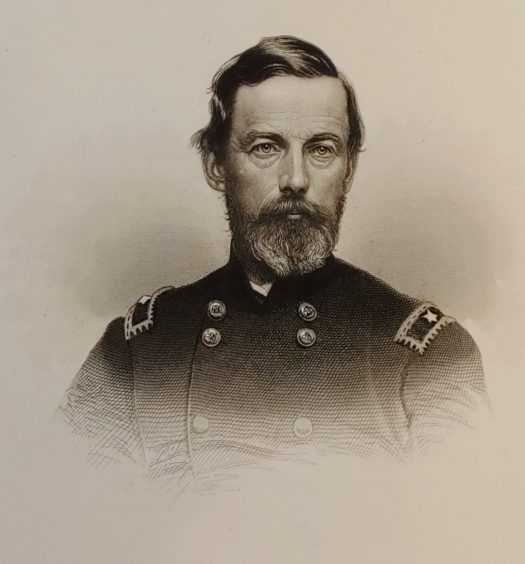

Second Lieutenant Charles E. Douglas of Providence was a jeweler who first served three months as a member of the First Rhode Island Detached Militia. As an officer he served three years in North Carolina with the Fifth Rhode Island Heavy Artillery (Robert Grandchamp Collection)

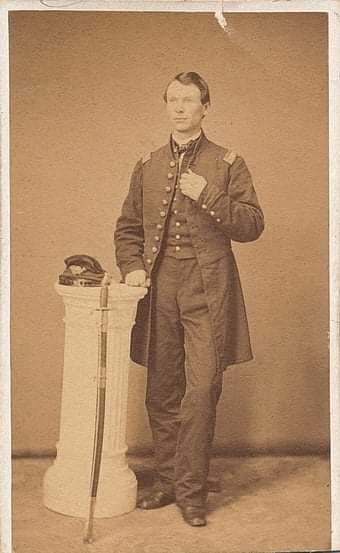

Private John Rice Arnold of Providence died of typhoid at his family home on July 30, 1861, shortly after returning from the front. He had served in Company D, First Rhode Island Detached Militia (Robert Grandchamp Collection)

As the Rhode Island Constitution states that the governor is the “captain-general” of the state militia, William Sprague accompanied the regiment to war. Field command was exercised, however, by Colonel Ambrose Burnside of Bristol. Although the regiment was called up on April 15, 1861, the First Rhode Island Detached Militia did not leave Providence until April 20, with a second detachment leaving on April 24. The delay in leaving the state was that because the regiment was composed of eight different militia companies, with eight different uniforms, a single new uniform had to be created from scratch. Impressively, the uniforms were quickly sewn by a group of ladies of Providence. The baggy blue blouses, gray pants, black hats, and red blankets they created became the trademark of the First Rhode Island Detachment Militia. A further delay occurred in acquiring new M1855 rifle-muskets from the Springfield Armory in Springfield, Massachusetts. Thus, armed and equipped, the First Rhode Island Detached Militia went to war.

The numbering of the Second, Fourth, and Seventh Rhode Island Volunteers is relatively straightforward: all three regiments were enlisted for three years. Recruited in May 1861, the Second was obviously the second regiment raised in Rhode Island. Recruited from throughout the state from militia companies that did not go out with the First Rhode Island Detached Militia, the Second went on to fight in every battle with the Army of the Potomac from Bull Run to Appomattox and was in existence until July 1865. The original Second Rhode Island was mustered out in June 1864; by then, the regiment was reduced to a small, three company battalion of barely 150 men in three companies. In late 1864, a recruiting campaign began in Rhode Island to bring the regiment back up to strength. Eventually five additional companies were raised, bringing the Second back up to eight companies in April 1865.

The Fourth Rhode Island recruited soldiers largely from northern and eastern Rhode Island in September 1861. It existed for three years, mustering out in October 1864. Some 220 men who had reenlisted or had joined the Fourth after it was mustered out were consolidated into three companies and merged with the Seventh Rhode Island Volunteers.

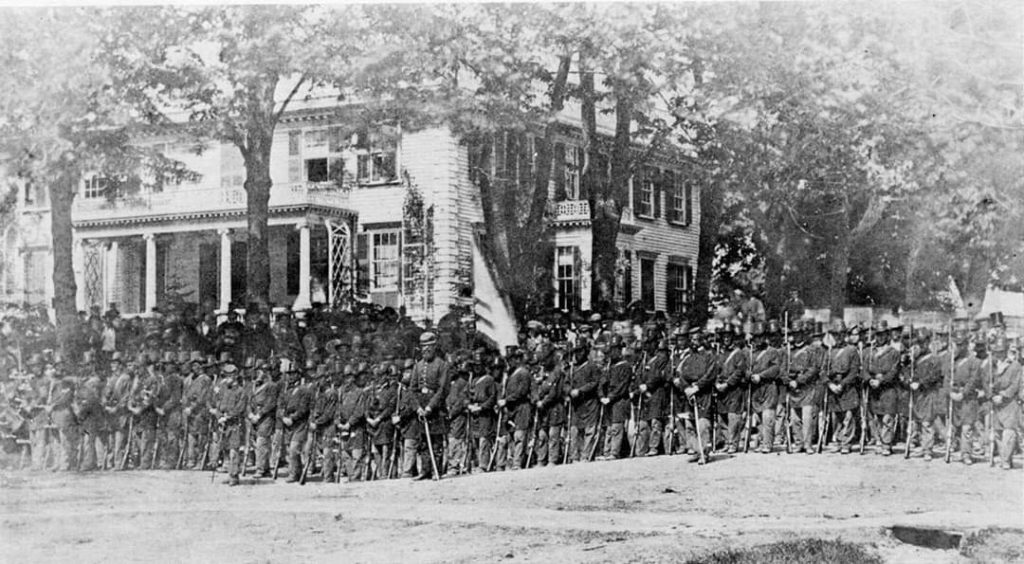

Company G, Second Rhode Island Volunteers, mustering into Federal service, June 1861 (Robert Grandchamp Collection)

The Seventh Rhode Island was the regiment that took the longest time for Rhode Island to recruit. Orders to form the unit came on May 22, 1862 and a recruiting station was opened in Providence, but few men initially joined. Finally, after a frantic call from President Lincoln in July 1862 after Union defeats in Virginia and when towns began to offer significant bounty payments, recruiting began to pick up in late July and into August 1862. Raised largely from towns in southern and western Rhode Island, the Seventh would be the only Rhode Island unit to serve in both the East and West during the war. Heavy casualties during the 1864 Overland Campaign caused the Seventh to be reduced to seven companies in October 1864. The regiment was merged with the three remaining companies of the Fourth Rhode Island to create a regiment still called the Seventh Rhode Island Volunteers. The original Seventh mustered out on June 9, 1865, but the three companies of veterans and recruits from the Fourth Rhode Island did not get back to Providence until July 1865.

The Ninth and Tenth Rhode Island Volunteers were both raised on May 26, 1862. The enlistees were to serve three months at a time when it was feared Stonewall Jackson, then campaigning in the Shenandoah Valley, would attack Washington, D.C. Both units left the state within forty-eight hours of receiving the call. The Tenth was composed exclusively of militia companies from Providence, with Company B, being made up largely of students from Providence High School and Brown University, and led by former governor Elisha Dyer, Sr. The Ninth was composed of various militia units from throughout Rhode Island including the Slater Drill Corps, Warren Artillery, Cudsworth Zouaves, Kentish Artillery, and Pettaquamscutt Guards. Both units served three uneventful months in the fortifications surrounding Washington, D.C. before returning to Rhode Island for muster out on September 1, 1862.

The Eleventh and Twelfth Rhode Island Volunteers were each recruited for a nine-month term in September 1862. The Eleventh recruited enlistees in Providence and the Blackstone Valley, while the Twelfth recruited men from throughout the state. Both regiments existed for just about ten months, with the Eleventh largely performing garrison duty in the nation’s capital, and the Twelfth seeing field service in Virginia and Kentucky, including combat at the bloody Battle of Fredericksburg.

Readers will note that Rhode Island never recruited the Sixth or Eighth Regiments. The stories behind that are complicated, but interesting.

In the summer of 1862, Governor Sprague envisioned the Sixth Rhode Island Volunteers as a “black” regiment, to be composed of African Americans. As Rhode Island had recruited the First Rhode Island Regiment in the American Revolution, composed of slaves freed by enlisting, free blacks, Narragansett and Wampanoag Indians, and other men of color, Sprague hoped that the Sixth Rhode Island would be the first black regiment recruited in the North. If Sprague had succeeded, the regiment would have beat the famed Fifty-Fourth Massachusetts Regiment to the front, as the Fifty-Fourth did not seriously start to recruit until the winter of 1863.

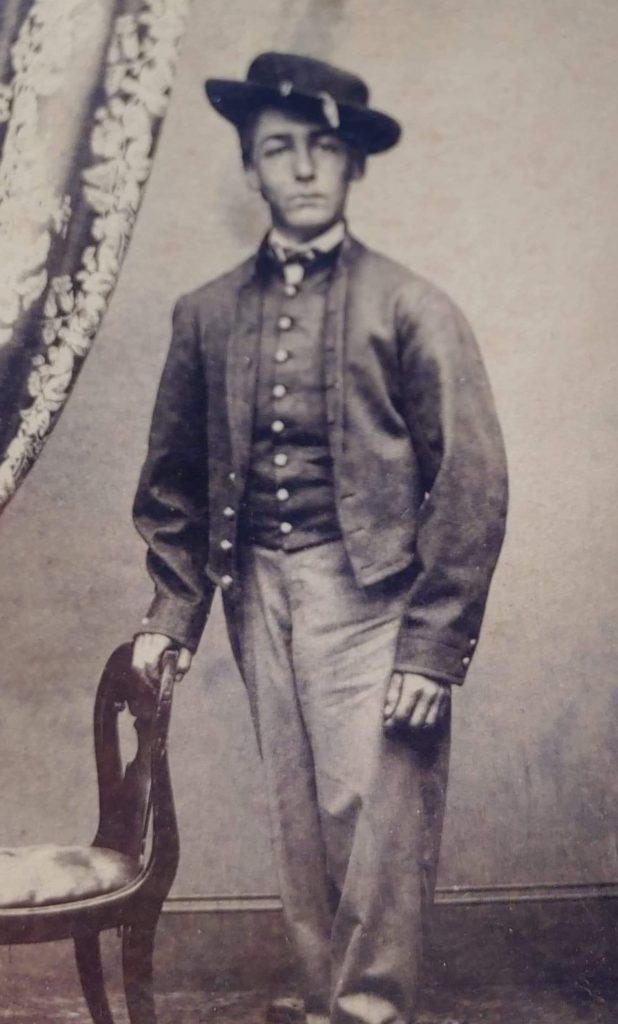

A member of the Narragansett Tribe, George T. Browning of Hopkinton served in the Seventh Rhode Island and was wounded at Cold Harbor. He later moved to Montana and was one of the last survivors of the Seventh (Robert Grandchamp Collection)

The black community of Providence responded favorably to the idea of a new regiment. Community meetings were held, and nearly one hundred men enrolled in the Sixth Rhode Island. This was a time, however, before the President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which freed enslaved people in Confederate territory. Before this major policy change, blacks were not permitted to assume a combat role. Instead, they served as laborers—a crucial role in any army, but it was not how wars were won and glory was gained. From Washington, D.C., Secretary of War Edwin Stanton notified Governor Sprague that the regiment’s soldiers would be relegated to a non-combat role as laborers, rather than as fighting men. Unwilling to send Rhode Island blacks to the front as laborers, rather than soldiers, Governor Sprague ordered recruiting to cease. As a result, the Sixth Rhode Island never mustered into Federal service and the number was never used.

Like the Sixth Rhode Island, the Eighth Rhode Island was never mustered into Federal service. When the call went out for militia companies to respond to the call for troops for the defense of Washington, D.C. in May 1862, Governor Sprague envisioned sending a brigade of three regiments from Rhode Island to the capital’s defense for three months. As stated above, the Tenth was composed exclusively of militia companies from Providence. The Eighth was to be composed of militia units from Washington, Kent, and Newport Counties, while the Ninth was to be composed of militia companies from Providence and Bristol Counties.

An engraver by trade, George A. Spencer of Bristol served in both the Tenth and Seventh Rhode Island Regiments. He was captured at Fredericksburg, but later mustered into the Seventh in June 1865 (Varnum Memorial Museum)

Recruitment for the Eight Regiment was haphazard due to the emergency nature of the call-up. Militia companies did not enlist in their entirety; rather, individuals from these companies volunteered for service. Hastily raised, equipped, and armed, the troops for these regiments left the state within forty-eight hours of receiving the call. When they arrived in Washington, D.C., the Confederate threat had largely subsided. It was quickly discovered, however, that only about 1,900 Rhode Island men had responded. This was only enough for two regiments, not the three Sprague had envisioned. By May 30, the situation was ironed out when the regiments were mustered into Federal service in Washington, D.C. The City of Providence companies were designated as the Tenth Rhode Island Volunteers. The companies from Washington, Kent, Newport, Bristol, and Providence Counties were designated as the Ninth Rhode Island Volunteers. The number Eight was not used, so there was no Eighth Rhode Island Volunteers.

The Thirteenth Rhode Island Volunteers was the regiment featured in the 2010 mockumentary “The Battle of Pussy Willow Creek,” which is an alternate history of the Civil War. Although a rather comical, tongue in cheek view of Civil War history, there actually was a Thirteenth Rhode Island Volunteers!

Rhode Island Governor James Y. Smith activated the Thirteenth Rhode Island in mid-June 1863 in response to the Confederate invasion of Pennsylvania. It was anticipated that the Thirteenth would be needed to garrison either Baltimore, Maryland, or Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Men were enrolled in the regiment to serve for six months. However, the great Union victory at the Battle of Gettysburg ended the need for short-term militia regiments. As such, the Thirteenth Rhode Island was ordered to disband. Most of the men, however, promptly reenlisted and formed the nucleus of the Third Rhode Island Cavalry, which was called up in July 1863. Sent to Louisiana, the Third Rhode Island Cavalry served until November 1865, becoming the last Rhode Island regiment to return home.

Readers will further note that the numbers Three and Five have not yet been discussed. Both units were heavy artillery regiments with a very different story.

The Third Rhode Island was originally recruited as an infantry regiment in August 1861. Designated early on to serve as part of General Thomas West Sherman’s South Carolina Expedition, the Third was sent to Fort Hamilton, New York, to learn heavy artillery drill. The Third Rhode Island became the first heavy artillery regiment in volunteer service. It was renamed the Third Rhode Island Heavy Artillery in November 1861. The regiment used its heavy guns to great effect in April 1862, helping to force Fort Pulaski in Georgia to capitulate.

As originally recruited, the Third was a regiment of 1,000 men in ten companies of 100 men each. However, a heavy artillery regiment in the Union Army had a completely different organization—it was 1,800 men at full strength, in twelve companies of 150 men each. Furthermore, the regiment of twelve companies was organized into three battalions of four companies each. Beginning in January 1862, the Third raised two additional companies, and recruited nearly 500 more men to bring the regiment up to full strength as a heavy artillery unit. The Third was the largest unit Rhode Island sent to the war with over 3,000 men on the rolls throughout the war. The regiment existed until August 1865 and was consolidated over time until finally only a single four company battalion remained. The Third was a remarkable regiment that saw combat service in Virginia, South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. The regiment never served entirely together. Instead, individual companies saw service as both heavy and light artillery, frontline service as both infantry and engineers, and service with the Navy, manning guns onboard gunboats off the Carolina coast.

The Fifth Rhode Island was originally recruited as a five-company battalion in late 1861. The regiment spent its entire service in North Carolina. After service in the successful Burnside Expedition, in the summer of 1862, the Fifth Rhode Island Battalion was redesignated as a regiment and five additional companies were recruited to bring it up to full ten company strength. In January 1863, however, the Fifth was redesignated as a heavy artillery regiment to man forts along the North Carolina coast. Interestingly, the regiment was never authorized to recruit the additional companies and numbers to bring the Fifth up to full strength as a heavy artillery unit. Accordingly, the Fifth, although a heavy artillery regiment, remained at ten companies throughout the war.

Both the Third and Fifth Rhode Island Heavy Artillery Regiments maintained the numbers Three and Five during the war. Typically, when an infantry regiment was converted into a heavy artillery regiment, the unit designation would change. For example, the Second Connecticut Heavy Artillery was originally the Nineteenth Connecticut Infantry, and the Eleventh Vermont Volunteers was later redesignated as the First Vermont Heavy Artillery. Although redesignated as heavy artillery units, the Third and Fifth never changed their numerical designation.

The Fourteenth Rhode Island was the state’s African American regiment during the Civil War. Although the Sixth Rhode Island failed to muster in the summer of 1862, policies about using black troops in combat roles had changed dramatically in the summer of 1863 with the impact of the Emancipation Proclamation in full effect. By then, United States Colored Troops units had been raised in the South, and black regiments had been established in the North, such as the Fifty-Fourth and Fifty-Fifth Massachusetts, as well as the Twenty-Ninth Connecticut. Now black troops had the full backing of the United States government and were used as front-line combat troops.

First Lieutenant Stephen M. Hopkins of Burrillville represented his hometown in the Rhode Island General Assembly. As a member of Company I, Twelfth Rhode Island Volunteers he was mortally wounded at Fredericksburg leading his company and died December 26, 1862 (Robert Grandchamp Collection)

Governor Smith received permission from the War Department to recruit two companies of heavy artillery composed of black recruits from Rhode Island. Smith’s idea was that the two companies would garrison forts along Narragansett Bay. Rhode Island African Americans responded enthusiastically to the call, and soon the two companies were full. Smith then received permission to recruit a four-company battalion. A week later he was authorized to form a full regiment of heavy artillery composed of black enlisted men.

The problem from the beginning was that Rhode Island’s small population of blacks could not support a full 1,800-man regiment. Only around 300 Rhode Island blacks, Narragansetts, Wampanoags, and other men of color joined the regiment. (As was the case with other black regiments, the Fourteenth was officered by white men.) To raise the rest of the numbers required, recruiters fanned out throughout the North, bringing in men from New York, Ohio, Kentucky, Pennsylvania, among others. Unfortunately, many of these illiterate recruits were swindled out of their bounty money by scammers. Despite the issues in raising the regiment, in the fall of 1863, the Fourteenth was sent to Louisiana, one four-company battalion at a time.

Sent to garrison New Orleans, Plaquemine, and Baton Rouge in Louisiana, the Fourteenth, like the Third, never served together as a full regiment. In 1864, in response to Confederate threats of retaliation against black units, and to fully legitimize them as units of the United States Army, all state-raised black regiments, with the exception of the units raised in Massachusetts and Connecticut, received new designations. Accordingly, on April 4, 1864, the Fourteenth Rhode Island Heavy Artillery became the Eighth United States Colored Heavy Artillery. Six weeks later, the numbers were changed again and the regiment’s numerical designation increased by three—to the Eleventh United States Colored Heavy Artillery. The Eleventh served in Louisiana until mustered out in October 1865.

The First Rhode Island Cavalry began its existence in 1861 as the First New England Cavalry. Governor Sprague had the idea in the fall of 1861 to form a cavalry unit composed of units from all the New England states. Prior to this, only infantry and artillery units had been raised in New England. The governors of Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine, Connecticut, and Massachusetts signed on to Sprague’s plan wherein each state would recruit one squadron of two companies for the regiment (a cavalry regiment was composed of twelve companies, split into three battalions of two squadrons each).

Recruits leaped at the chance to join a cavalry unit, so much so that Vermont, Maine, and Massachusetts each recruited a full regiment. Connecticut recruited a four-company battalion that was later attached to a New York unit. Rhode Island ended up with eight companies, while New Hampshire recruited four companies. The regiment was composed of men from New Hampshire and Rhode Island, with a unique flag bearing the seals of both states. It went to war as the First New England Cavalry. In July 1862, much to the disgust of the unit’s New Hampshiremen, the regiment was redesignated as the First Rhode Island Cavalry. The New Hampshiremen soldiered on until late 1863 when they were sent home to form the nucleus of the First New Hampshire Cavalry, and the eight Rhode Island companies were consolidated into a battalion of four companies that remained in the field until General Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox.

The Seventh Squadron of Rhode Island Cavalry is a unit that falls out of the number sequence! It was conceived by Sanford Burr, a college student at Dartmouth, who hoped to recruit a unit of cavalrymen to serve in the Union Army for three months in the summer of 1862. His motivations are unclear, but Burr successfully sold the idea to several of his fellow students from Dartmouth, Norwich, Bowdoin, Amherst, and Union Colleges. In addition, some fifteen men from the Woodstock, Vermont, area decided to join Burr. Burr offered his company of some eighty men to the governors of all the New England states, but only Governor Sprague accepted the unit for three months, as part of the quota under which the Ninth and Tenth Regiments were activated. Rather than send a single company to war, Sprague hastily organized a company in Providence to serve with the “College Cavaliers,” as Burr’s men were called.

Severely wounded July 2, 1863 at Gettysburg, Lieutenant T. Fred Brown of Providence led Battery B, First Rhode Island Light Artillery. Recently his uniforms and papers were donated to the Varnum Memorial Museum in East Greenwich and is now part of its outstanding Civil War collection (Robert Grandchamp Collection)

Why the unit was called the Seventh Squadron is a story of its own. As stated above, a cavalry squadron was composed of two companies, and there were six squadrons in a full regiment of cavalry. The original idea was to attach the Seventh Squadron to the First Rhode Island Cavalry for the duration of its three-month service. When the cavalrymen arrived in Washington, D.C., however, the two Rhode Island companies, under the command of Major Augustus Corliss, were immediately sent to the Shenandoah Valley to act as scouts. Therefore, the two companies never served with the rest of the First Rhode Island Cavalry. The Seventh Squadron’s three months in the summer of 1862 were largely uneventful. The unit did take part in the Union cavalry’s dramatic escape from Harpers Ferry on the night of September 14-15, 1862, after which the unit returned to Providence for muster out. Many of the men in Burr’s company went on to become doctors, lawyers, minsters, and businessmen. They had a lifetime of stories from their three months in the Seventh Squadron of Rhode Island Cavalry.

The Second Rhode Island Cavalry was only in existence for ten months. Composed largely of “worthless” bounty jumpers from New York City, with only a smattering of Rhode Islanders in the ranks, the unit was sent to Louisiana where men deserted by the score, and others died of disease. After a lackluster showing at the Battle of Port Hudson, the Second Cavalry was ordered consolidated with the First Louisiana Cavalry, a unit composed of white southerners loyal to the Union. This move led to a mutiny in the Second Rhode Island, as they refused to serve with another regiment. Two men were executed for their role in the events. Finally, in January 1864, the surviving men were consolidated into two companies and transferred to the Third Rhode Island Cavalry.

During the Civil War, the light artillery batteries sent from Rhode Island were known as the finest in the Union Army. After the war, the veterans quipped that some generals would not begin a battle unless a Rhode Island battery was on the field. The same veterans also called the First Rhode Island Light Artillery, “The Geography Class,” due to its wide and varied service. At one point in July 1863, five batteries were with the Army of the Potomac at Gettysburg, one was on duty in the defenses of Washington, another was in North Carolina, while still an eighth was on duty in Kentucky!

The key to the success behind the Rhode Island Artillery in the Civil War was the Providence Marine Corps of Artillery (PMCA). Raised in 1801, the PMCA was the first battery of “flying artillery” organized outside of the United States Army. Using light guns, the artillerymen of the PMCA wowed audiences with their perfection in drill, rapidity of fire, and fast paced maneuvers in drill exhibitions they took part in throughout the North before the war. The PMCA became known as the “Mother of Batteries,” as all Rhode Island light artillerymen were recruited and trained by the PMCA during the war.

Unlike most northern states which employed the “battery system,” wherein light artillery batteries were recruited independently and numbered as such, Rhode Island maintained a full eight battery regiment of light artillery during the war, with two exceptions.

The First Rhode Island Battery was the first unit to leave Rhode Island, departing on April 18, 1861. It was composed exclusively of PMCA members to serve three months. The numbering is obvious because it literally was the first battery of light artillery from Rhode Island. They were also the first volunteer battery mustered into Federal service, and the first battery in the history of the United States Army to use rifled cannons.

The Tenth Rhode Battery, so named because it was the tenth light artillery battery raised in Rhode Island, was also composed of PMCA members and served three months in the summer of 1862 as part of the same call up for the Ninth and Tenth Regiments. The battery was again activated in the summer of 1863 and served about six weeks at “The Bonnet” in North Kingstown, helping to defend Narragansett Bay.

The First Rhode Island Light Artillery Regiment was commanded by Colonel Charles H. Tompkins, who had served as captain of the First Battery. The regiment was composed of eight batteries designated Batteries A, B, C, D, E, F, G, and H. Although the regiment existed on paper, the batteries served independently of the regiment. In effect, Tompkins’s regimental headquarters served as the de facto headquarters of the Sixth Corps Artillery Brigade from Chancellorsville until the end of the war.

It was not until September 1861 that the full eight battery regiment of light artillery was authorized. By then, Rhode Island had already recruited and sent to the front four additional batteries to serve for three years. As such the Second Battery was redesignated as Battery A, the Third Battery as Battery B, the Fourth Battery as Battery C, and the Fifth Battery as Battery D. In August 1864, Battery A was consolidated with Battery B, maintaining the designation of Battery B, while in January 1865, Batteries C and G, both of which had suffered grievous losses at the Battle of Cedar Creek, were combined to form a new Battery G.

Private Charles D. Ennis of Charlestown served in Battery G, First Rhode Island Light Artillery. He earned the Medal of Honor for heroism at the Battle of Petersburg, Virginia, for his brave actions on April 2, 1865 (Robert Grandchamp Collection)

Rhode Island is officially credited with sending 23,236 men to serve in the United States military during the Civil War. These men served in eight infantry regiments, three heavy artillery regiments, ten batteries of light artillery, a company of hospital guards, three cavalry regiments, and a squadron of cavalry. Furthermore, hundreds of Rhode Islanders served with federal units in the United States Army, Navy, and Marine Corps. Although their regimental designations may have changed at points during the Civil War, the units Rhode Island sent were highly regarded by the government they swore to protect. They upheld the last words of Colonel John Stanton Slocum to “Show Them What Rhode Island Can Do!” A total of 2,217 Rhode Islanders are known to have died in service in the Civil War.