Hostilities between the New England colonies and Great Britain did not break out until April 19, 1775, at the Battle of Lexington and Concord. But Rhode Island’s government took a bold military act against the British Crown in preparation for the possibility of war with the mother country in early December of 1774. Fast and bold decision-making by Rhode Island Patriots directly spurred Connecticut and New Hampshire Patriots to do the same in their colonies.

In fact, at the New Hampshire fort, Patriot and Crown forces confronted each other. The British fired cannon at the Patriots. Thus, the war could have started then, all because of what Rhode Island started.

Tensions had been building between Patriots, on the one side, and Crown authorities and Tories (their American supporters) on the other side, ever since the Boston Tea Party in December 1773. Parliament had responded by shutting down the port of Boston, replacing the civilian governor with British general Thomas Gage, and closing meetings of the General Assembly and county courts. In order to coordinate their responses, twelve of the thirteen colonies (not Georgia) met at the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia. In October 1774, Congress resolved to impose a boycott on American merchants purchasing British goods until Parliament withdrew its acts punishing Boston.

Believing that matters were heading toward armed conflict, on October 20, 1774, in London, King George III issued orders in council prohibiting the exportation of arms and ammunition from Great Britain. The King did not want any of the weapons or gunpowder ending up in the hands of “rebels” in North America. In sending copies of the orders to the governors of the thirteen colonies of mainland North American, William Legge, Earl of Dartmouth, the minister in London in charge of colonial affairs of North America, further directed that governors of the thirteen colonies take “the most effectual measures for arresting, detaining, and securing” any armaments that colonists attempted to import.[1]

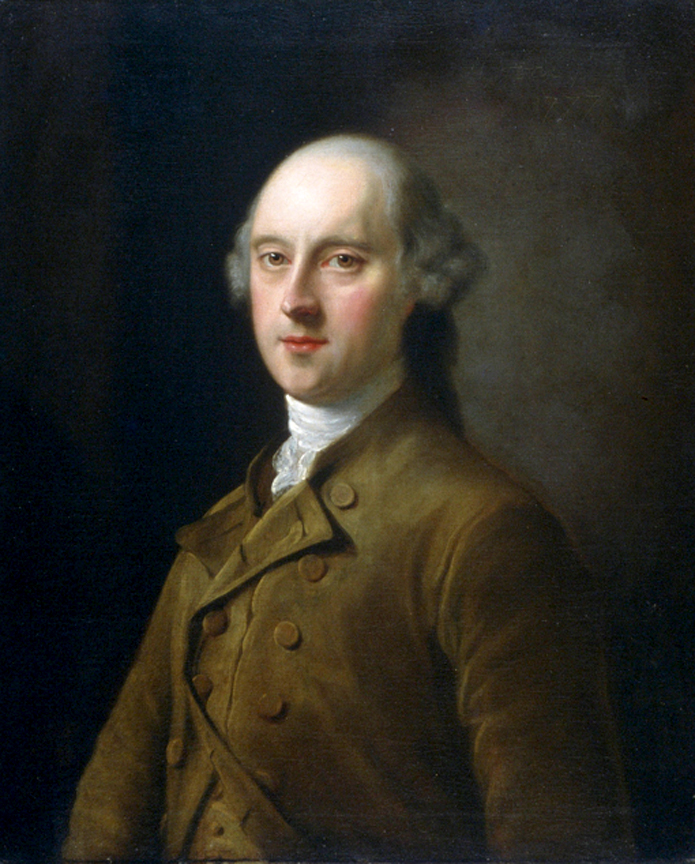

William Legge, Earl of Dartmouth issued orders to governors of the thirteen colonies that spurred Rhode Island to seize cannon at Fort George in Newport

The orders in council arrived in Providence in the evening of December 7 and were placed before Rhode Island’s General Assembly the next morning. The orders had the opposite effect of King George’s intention, as it galvanized colonial military preparations, beginning in Rhode Island.

Lord North meant for the orders to be confidential, known only to the Royal governors and their agents, but he overlooked that Rhode Island (and Connecticut) had elected governors. The Providence Gazette was immediately provided of the copy of the order, which it published in its June 10 edition, along with Lord Dartmouth’s accompanying directive.[2]

Samuel Ward of Westerly and Newport served as one of Rhode Island’s delegates to the First Continental Congress that met in Philadelphia. The former Rhode Island governor met there John Dickinson of Pennsylvania and Richard Henry Lee of Virginia, two of the leading Patriots attending the congressional session. Ward wrote a letter to them explaining what happened after the orders in council arrived in Providence:

The Letter from Lord Dartmouth and the Copy of the King’s Order in Council, Copies of which are enclosed, were brought by the [Royal Navy warship HMS] Scarborough, received by Express [at Providence] on Wednesday Evening last [December 7] and next Morning laid before the General Assembly. They [members of the General Assembly] immediately ordered Copies of them to be sent to Mr. [Thomas] Cushing [a leading Patriot in Boston] to be communicated to the Massachusetts provincial Congress. They [the members of Rhode Island’s General Assembly] ordered the Cannon at our Fort which was not tenable to be sent to Providence where it will be safe and ready for Service. . . .[3]

The fort mentioned was Fort George, located on Goat Island in Newport Harbor. The stone fort’s cannon commanded the entrance to Newport Harbor.

William Legge, Earl of Dartmouth issued orders to governors of the thirteen colonies that spurred Rhode Island to seize cannon at Fort George in Newport

That evening, ten ships from Providence were sent to Newport to take aboard the artillery at Fort George and carry them back to Providence. They accomplished their task efficiently. Fortunately for them, Captain James Wallace of the Royal Navy was not, at that time, patrolling Narragansett Bay. In the prior months, he had been patrolling the bay, threatening to bombard Newport, sending troops ashore to steal cattle and sheep to feed his sailors, and burning houses in Jamestown. But at that this time, he was on a mission outside of Rhode Island.

The Newport Mercury, published by firm Patriot Solomon Southwick, wrote of the affair in its December 12 edition:

Last Friday and Saturday [December 9 and 10] all the cannon belonging to Fort George, except 4, were carried to Providence, with the shot, &c., from whence they may be easily conveyed into the country, to meet the Indians and Canadians with which the colonies are threatened.

The Tory faction in this town [Newport], the beginning of last week, grinn’d horrible a gastly smile, and prophesied there would be high fun by Saturday night; however, they have been somehow most shockingly disappointed, as ‘tis hoped they always will be.[4]

Southwick gave as the purported rationale for the seizure the need of Rhode Island’s military in Providence to confront a threat from “the Indians and Canadians” to the North. Of course, this was nonsense. It recalls many protestors at the Boston Tea Party dressing as Narragansetts as they threw boxes of tea into Boston Harbor. Of course, the Narragansetts were just used as a disguise.[5]

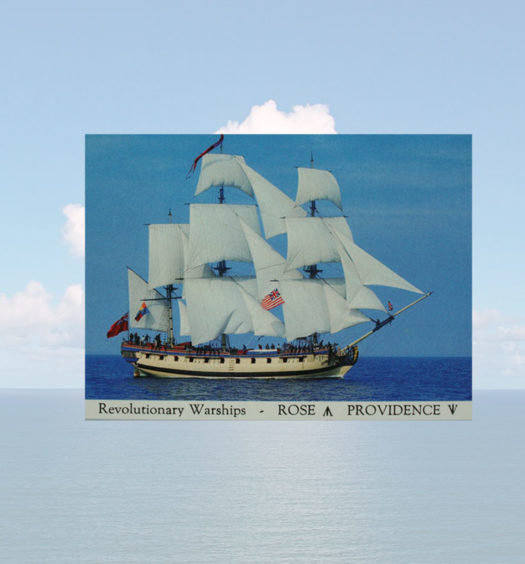

The day after Captain James Wallace arrived back in Narragansett Bay, December 12, on board his 20-gun warship, the HMS Rose, he wrote his superior in Boston, Admiral Samuel Graves a letter, which reads in part:

Sir, Yesterday I arrived in this port, with His Majesty’s Ship under my Command, from New London, on a cruise, of which I had the honor to acquaint You, [in my letter of] the 8th instant.

Since my absence from this Place, I find the Inhabitants (they say here of Providence) have seized upon the King’s Cannon that was upon Fort Island [also called Goat Island], consisting of six twenty-four Pounders, eighteen eighteen-Pounders, fourteen six-Pounders, and six four-Pounders (the latter they say, formerly belonged to a Province [Rhode Island] Sloop they had here) and conveyed them to Providence.

A procedure so extraordinary, caused me to visit upon the Governor [Joseph Wanton of Newport], to inquire of him, for your information, why such a step had been taken. He very frankly told me, they had done it to prevent their [the cannon, from] falling into the hands of the King, or any of his Servants; and that they meant to make use of them, to defend themselves against any power that shall offer to molest them.

I then mentioned, if, in the course of carrying on the King’s Service, I should ask assistance, whether I might expect any from him, or any others in the Government.

He answered as to himself he had no Power, and in respect to any other part of the Government I should meet with nothing but opposition and difficulty. So much for Governor Wanton.[6]

Naturally, Captain Wallace was amazed by this response from the Rhode Island governor.

On December 14, a Newport Tory wrote a letter he sent to New York for publication in James Rivington’s New York Gazette, which supported the Crown. No newspaper in Rhode Island would publish it. The letter, set forth in the newspaper’s December 29 edition, reads in part:

The people here have, I think openly declared themselves against [Royal] government, and in such a manner, as surely must be pronounced rebellion. Is it possible that a people without arms, ammunition, money, or navy, should dare to brave a nation, dreaded and respected by all the powers on earth. What black ingratitude to the parent state [i.e., Great Britain], who has nourished, protected and supported them from their infancy. What can these things indicate but a civil war? Horrid reflection! And such as freezes the blood of every humane heart. There has been a most extraordinary movement here a few days ago. The public authority of the Colony have dismantled the King’s fort, and moved all the cannon and stores to Providence, in order, it is said, to assist the Bostonians, against the King’s troops.

Underneath is a list of the cannon

6 24-Pounders

18 18-ditto, given by the late King [King George II] to the fort

l4 6-4 ditto belonging to the [Rhode Island] colony

God send us better times.[7]

Cannon at Red Bank Battlefield in New Jersey, the scene of a stunning victory by Rhode Island Continental troops in October 1777 during the Revolutionary War (Christian McBurney)

The General Assembly’s quick and decisive actions came to the attention of two other colonies, Connecticut and New Hampshire. The Connecticut Gazette, a Patriot newspaper published in New London, included the following in its December 16 edition:

Last Friday [December 9] all the cannon belonging to Fort George at Newport, except 4, were carried to Providence, with the shot, &c. from whence they may be easily conveyed into any part of the country, to meet the Indians and Canadians, with which the Colonies are threatened. And on Tuesday last [December 13] the cannon belonging to the battery in this town [i.e., New London], were removed into the country, for the same purpose.[8]

New London merchant Nathaniel Shaw, who frequently dealt with Newport merchants, made it clear that the moved by New London Patriots was inspired by Rhode Island’s example. He wrote in a December 14 letter that New London Patriots had taken action “In consequence of the Cannon being moved from the fort att Newport to Providence . . . .”[9]

At Portsmouth, New Hampshire, a serious violent action against the Crown occurred at Fort William and Mary. At the time, New Hampshire’s governor was a firm Tory. The Patriot action was led by John Sullivan, a delegate to the Continental Congress and future major general who would command the American Army in the Rhode Island Campaign of August 1778 and at the Battle of Rhode Island on August 29, 1778. The action was spurred by concern that a Royal Navy ship was preparing to sail to Portsmouth to seize the gunpowder at Fort William and Mary.

A New Hampshire newspaper, in its edition dated December 17, 1774, described what occurred on December 14 at Portsmouth:

On Wednesday last [December 141 a Drum and fife [paraded] the streets of Portsmouth, accompanied by several Committeemen, and the Sons of Liberty, publickly avowing their intention of taking possession of Fort William and Mary, which was garrisoned by six invalids. After a great number of people had collected together, they embarked on board scows, boats, &c. entered the Fort, seized the Gunpowder, fired off the Guns, and carried the Powder up to Exeter, a Town fifteen miles distant. The quantity [of gunpowder] was about two hundred to two hundred and twenty barrels.[10]

According to American Revolution historian J. L. Bell, British soldiers fired cannon at the raiders, making it “the first time British regulars fired back at American units.”[11] Bell believes that this violent confrontation could have sparked the Revolutionary War four months before Lexington and Concord. The difference from Lexington and Concord was that no one was killed in New Hampshire.[12]

Rhode Island, again, was blamed for the Portsmouth, New Hampshire, action. The Royal governor of New Hampshire, John Wentworth, wrote Admiral Samuel Graves of the Royal Navy, “The Mischief originates from the publishing of . . . the King’s Order in Council at Rhode Island, prohibiting the exportation of military stores from Great Britain . . . .” Wentworth added that Paul Revere of Boston, who would gain fame for his ride on April 18, 1775, had brought the news about Rhode Island to Portsmouth Patriots.[13]

A cannon at Fort Moultrie National Historical Park on Sullivan’s Island near Charlestown, South Carolina. At what was then Fort Sullivan, in 1776 Patriot defenders drove off a Royal Navy squadron. This British 12-pounder cannon was probably made in the 1670s. Some of the cannon seized by Rhode Island may have been that old (Christian McBurney)

When Rhode Island’s General Assembly ordered the removal of cannon at Fort George to Providence, it also ordered that other warlike preparations be made. They were also described in Samuel Ward’s letter to Dickinson and Lee. The General Assembly, Ward wrote, ordered that:

200 bbls. Of Powder, a proportionate quantity of Lead & Flints & several Pieces of brass Cannon for the Artillery Compy. Were order’d to be purchased, a Major General (an officer never before chosen in the Colony) was appointed, several independent Companies of light Infantry Fusiliers, Hunters &c were formed, the Militia was order’d to be disciplined & the Commanding Officers empowered to march the Troops to the Assistance of any Sister Colony.

Ward added to the letter, which he forwarded to the Providence Gazette for publication:

The Spirit & Ardor with which all this was done gave Me ineffable Pleasure and I heartily wish that the other Colonies may proceed in the same spirited Manner for I fear the last Appeal to Heaven must now be made & if We are unprepared We must be undone. The Idea of taking up Arms against Great Britain is shocking but if We must become Slaves or fly to Arms I shall not hesitate one Moment which to chuse for all the Horrors of civil War & even Death itself in every Shape is infinitely preferable to Slavery which in one Word comprehends every Species of Distress Misery Infamy & Ruin.[14]

As historian J.L. Bell has written about all these preparations in Rhode Island:

Moving cannon to a more secure place, buying weaponry when the London government had just forbade that export, appointing a major general and forming new militia companies, invoking John Locke’s “Appeal to Heaven”—Ward’s Rhode Island was clearly preparing for war in December 1774.[15]

A Newport mob almost subject Captain James Wallce to violence on December 15. Wallace was sitting in the Newport home of Loyalist George Rome and other friends, when a man rushed into the house and breathlessly announced that “there was a Mob raising with an Intent to tarr and fear the Captain of the Man of War and the Man of the House,” meaning Captain Wallace and George Rome. Wallace shortly afterwards learned that the Newport mob “had broke the Custom-House windows and entered two or three other Gentlemen’s Houses and done some damage.” Wallace obtained reinforcements from his warship, but was not molested.[16] The Royal Navy captain fired off a letter to Governor Wanton, exclaiming, whether “War or Peace” was in the offing.[17]

Bell has written an excellent book about how General Thomas Gage, commander of the British forces in North America and stationed in Boston, wound up sending a major British army force to Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775. It was all about cannon, which was crucial to conducting warfare in this age. At the heart of Bell’s book are four small brass cannon stolen from militia armories in Boston, smuggled out of town to the countryside, and finally located by Royal spies in Concord. Bell’s book, The Road to Concord, How Four Stolen Cannon Ignited the Revolutionary War, tells the story of the importance of these four cannon leading to the first bloodshed at Lexington and Concord for the first time.

After the war started on April 19, 1775, Rhode Island authorities sought to take the rest of the cannon from Fort George and bring them to a more secure place near Providence. This was done on August 10, 1775, by a privateer from Providence, at a time, again, when Captain Wallace was on a mission outside Narragansett Bay. According to Newport minister Ezra Stiles, the cannon included “2 large 18 pounders.”[18]

Photograph of the replica of the HMS Rose warship, circa 1976. Captain James Wallace commanded the Rose and attempted to intimidate Rhode Islanders.

Rhode Island’s General Assembly appreciated the importance of cannon all along. These cannon would become useful to American forces after a large British invasion force seized Newport and the rest of Aquidneck Island (and Jamestown) in early December 1776, staying for three years. The cannon seized from Fort George in December 1774 and August 1775 was used at various gun emplacements surrounding Providence. The British never tried to attack Providence (thus preserving its eighteenth-century houses).

Another example of the military preparations of Rhode Island is to note the establishment of several independent infantry companies and artillery companies in 1774 and in 1775 prior to the Battle of Lexington and Concord. Here is a list as approved by the General Assembly and the dates of the sessions of the General Assembly at which the companies were approved:

The Light Infantry for the Providence County, incorporated in the June 1774 Session

Kentish Guards, incorporated in the October 1774 Session

Newport Light Infantry , Same

Providence Grenadier Company, Same

Pawtuxet Rangers, Same

The Company of Light Infantry from Gloucester, Same

Scituate Hunters, incorporated in the December 1774 Session

Train of Artillery, Providence County, Same

Providence Fusiliers, Same

North Providence Rangers, Same

Rhode Island was indeed preparing for war and, ultimately, independence.

Notes:

[1] Lord Dartmouth’s circular letter, dated Whitehall, Oct. 19, 1774, quoted in William Bell Clark, ed., Naval Documents of the American Revolution, vol. 1 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1964) (hereinafter “NDAR”), 10, n. 2. [2] Providence Gazette, Dec. 10, 1774, in NDAR, 9-10; see also General Assembly Resolutions, Dec. 1774 Sessions, in John R. Bartlett, ed., Records of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, vol. 7 (Providence: A. Crawford Greene, 1862), 262; . L. Bell, The Road to Concord, How Four Stolen Cannon Ignited the Revolutionary War (Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2016), 112. [3] Samuel Ward to John Dickinson, Dec. 14, 1775, in NDAR, 20. [4] Newport Mercury, December 12, 1774, in ibid., 14-15. [5] See J. L. Bell, “Narragansetts (Not Mohawks) Blamed for Boston Tea Party,” Dec. 9, 2023, The Online Review of Rhode Island History, https://smallstatebighistory.com/narragansetts-not-mohawks-blamed-for-boston-tea-party/. See also Christian McBurney, “Gaspee Raid Inspires Boston Tea Party Raiders to Disguise Themselves as Narragansetts,” Dec. 15, 2023, in ibid., https://smallstatebighistory.com/gaspee-raid-inspires-boston-tea-party-raiders-to-disguise-themselves-as-narragansetts/. [6] Captain James Wallace to Vice-Admiral Samuel Graves, Dec. 12, 1774, in NDAR, 15. [7] Extract of a Letter from Newport, Dated Dec. 14 [1774), James Rivington’s New York Gazette, Dec. 29, 1774, in ibid., 20.. [8] Nathaniel Shaw, Jr. to Eliphalet Dyer, Dec. 14, 1774, in ibid., 20. [9] Connecticut Courant (New London), Dec. 16, 1774, ibid., 30. [10] Letter from a Gentleman in New Hampshire to a Gentleman in New York, Dec. 17, 1774, in ibid., 30-31. [11] Bell, Road to Concord, 112. [12] J. L. Bell presentation at the Society of the Cincinnati’s headquarters at the Anderson House, Washington, D.C., April 29, 2025. [13] John Wentworth, Governor of New Hampshire, to Vice Admiral Samuel Graves, Dec. 14, 1774, in NDAR, 19. [14] Samuel Ward to John Dickinson, Dec. 14, 1775, in ibid., 20. [15] Bell, Road to Concord, 112. [16] James Wallace to Vice Admiral Samuel Graves, Dec. 15, 1774, in NDAR, 25-26. [17] Captain James Wallace to Joseph Wanton, Governor of Rode Island, Dec. 15, 1774, in ibid., 25. [18] Ezra Stiles Diary Entry, Aug. 10, 1775, in Franklin Bowditch Dexter, ed., The Literary Diary of Ezra Styles, D.D., LLC.D (New York: Scribner’s Sons, 1901), vol. 2, 659. [19] See General Assembly Resolutions, June 1774, Oct. 1774, and Dec. 1774 Sessions, in John R. Bartlett, ed., Records of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, vol. 7 (Providence: A. Crawford Greene, 1862), 247-48, 260, 262-69.