Visitors to Newport are sometimes informed that the luxurious hotel at 41 Mary Street in Newport, called The Vanderbilt, was originally built by Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt as a magnificent mansion for one of his mistresses. However, many Newporters insist the building was actually built as a YMCA. Which story is true?

In researching the tale, I came across the colorful but largely forgotten story of the fabulously wealthy Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt. This is his fascinating story and his impact on the city of Newport.

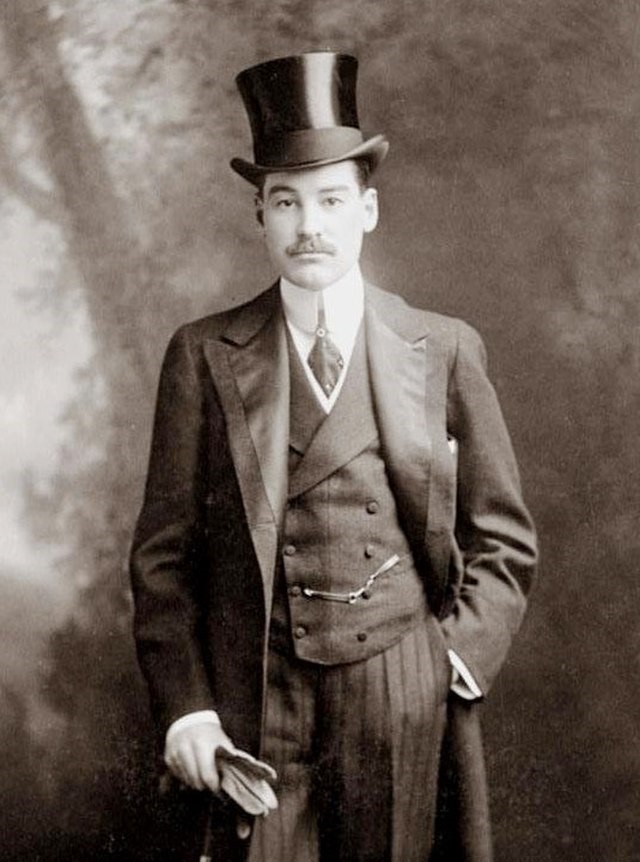

Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt

Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt, born in 1877, was the third son of Cornelius Vanderbilt II and Alice Claypoole Gwynne. Cornelius II was head of the Vanderbilt family, chairman of the New York Central Railroad, and one of the richest men in the world. He and Alice built the most famous of Newport’s mansions, The Breakers.

Young Alfred was known as “the handsome Vanderbilt.” He expected his oldest brother William Henry Vanderbilt II would inherit the family businesses allowing him to lead the life of the idle rich. When Alfred was fifteen, however, William died of typhoid fever. Then, in 1895, the oldest surviving son, Cornelis Vanderbilt III, known as Nelly, despite his father’s strong objections and threats to disinherit him, married one the “marrying Wilsons” (another colorful story). This potentially put Alfred first in line to inherit the bulk of his wealthy father’s estate.

After Alfred graduated from Yale University (Class of 1899), where he was voted the most popular man on campus, he and friends embarked on a two-year round-the-world tour. He was in Japan in September 1899 when he received word that his father had died. Alfred rushed home for the reading of the will. It turned out that Cornelius II had carried out his threat and had virtually disinherited Nelly. (He received just $500,000 and the income from a $1 million trust fund. Nelly went on to be a military officer, inventor, engineer, and yachtsman.) Alfred unexpectedly became the head of the New York Central Railroad. He personally inherited some $42 million dollars (equivalent to nearly $1.5 billion today) making him one of the richest men in the world.

Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt has largely faded from history. In the book Fortune’s Children, The Fall of the House of Vanderbilt, the author and distant relative, Arthur T. Vanderbilt II, makes only a few passing refences to Alfred and does not include a single photograph of him. The Vanderbilts (Harry N. Abrams, 1989), by Jerry E. Patterson, a go-to resource for all things Vanderbilt, mentions Alfred only briefly. Why was that the case?

Part of the reason may be the lifestyle he chose. Alfred’s father, Cornelius II, was stern, religious, and a workaholic. He took his position as head of the New York Central Railroad seriously. Alfred had little interest in business and left the day-to-day operation of the railroad to relatives. His passion was breeding and showing horses, reviving the archaic English sport of coaching (which is explained below), and beautiful women.

Cornelius II left The Breakers to his wife, Alice. She was known as “Alice of the Breakers” and summered in Newport and ruled society with an iron fist. Alfred had an apartment in New York City and summered in Newport. Rather than move in with his mother for the 1900 summer, he rented Rockry Hall on Bellevue Avenue.

Alfred Gwynn Vanderbilt in coaching attire driving one of his carriages, with Ellen Tuck French at his side. She was Alfred’s first wife and the mother of their child, William Henry Vanderbilt III, the fifty-ninth governor of Rhode Island (Author’s collection)

Alfred inherited his father’s 450-acre Oakland Farm in Portsmouth, Rhode Island. It would become an important part of his life.

Oakland Farm was originally part of 100 acres granted to Thomas Cornell in 1664. In 1778, during the Revolutionary War, it was said that General John Sullivan, commander of the American army during the Rhode Island Campaign, used Oakland Farm as his headquarters during the siege of British-held Newport. A skirmish in the opening phase of the Battle of Rhode Island took place near the land. In 1867, the farm was sold to Augustus Belmont a wealthy financier, horse-breeder, and racehorse owner. (He founded The Belmont Stakes, the third leg of the Triple Crown series of American Thoroughbred horse racing. A statue of Augustus Belmont sits on the grounds of the headquarters of The Preservation Society of Newport County at Bellevue and Narragansett Avenues.) Nine years later Belmont sold the farm to Cornelius Vanderbilt II.

On January 11, 1901, Alfred married Ellen “Elise” Tuck French, daughter of the wealthy president of the Manhattan Trust Company. Like her husband, Elise summered in Newport and was interested in horses as a hobby. Later that year the newlyweds had their only child, William Henry Vanderbilt III.

Beginning in 1901, Alfred set about transforming rural Oakland Farm into a summer home and one of the most luxurious horse farms of the times. He added extensively to the colonial era main house. One of the most striking features of the expanded house was a large oval second floor window set in a massive field-stone chimney.

As luxurious as the house was, what most struck visitors were the massive shingle style outbuildings. There was a cattle barn located on what is now part of Green Valley Golf Course. The expansive Vanderbilt horse stable near the house was one of the largest and finest private stables in the world. It could hold ninety horses and an adjacent building stored Alfred’s many carriages and coaches.

No longer dominated by his father and with virtually unlimited wealth Alfred Vanderbilt embraced everything to do with horses. At Oakland Farm he employed a staff to breed and train thoroughbreds for show and for coaching events throughout the United States and Europe. His horses won blue ribbons at every major show. He spent more and more and more time with his horses and as little time as possible at the New York Central Railroad offices.

As his obsession for horses grew, he began building a private riding ring. This huge wooden structure was 265-feet long, 125-feet wide, with a 65-foot-high ceiling. In 1906 the Newport Journal described it in a headline as, “A Mammoth Building, Largest Private Structure of its Kind in the World.”

In addition to the ring, the building included a swimming pool, trophy room, library, squash and tennis courts, and a balcony that could accommodate 200 guests. To connect the stable to the riding ring Alfred built a steam-heated passageway so his beloved horses could be kept under cover and out of inclement weather when moving between the two buildings. He also constructed a polo field on the south part of the farm.

Alfred and Elise attended every major East Coast horse show. But with a young child, she soon began spending less time at shows and more time at Oakland Farm.

Meanwhile, the sport of coaching took over Alfred’s life. He traveled to horse shows and coaching events, typically living in his luxurious two-bedroom private railroad car, the Wayfarer.

The origins of coaching go back to English 18th and early 19th century horse-drawn mail coaches. Mail coaches were eventually replaced by railroads, but nostalgia for the horse-drawn mail coaches led to the development of coaching as a sport. The heavy coaches were pulled by four horses and controlled by one driver, known as a “whip.” The whip wore special attire and sat in an elevated front box seat. The whip had to drive the coach holding all the reigns in one hand, which required skill and experience. At least two costumed footmen rode on a rear bench. Center benches held the passengers. Coaching was (and still is) a very expensive pursuit. It was an important part of the Gilded Age Newport’s summer season.

Many wealthy sons of America’s rich and powerful took up the sport of coaching, but not to the extent that Alfred did. While others were content hiring professional drivers, Alfred drove his coach himself. He began to dress more and more like his stable staff and less like one the world’s wealthiest men.

In 1902 Alfred and his friend and fellow coaching enthusiast James H. Hyde, heir to the Equitable Life Assurance fortune, started a commercial coaching enterprise. They took passengers for $12 ($15 to sit in the box seat next to Alfred) twice a week from late spring to fall from New York City to Philadelphia. Since the upkeep of a coach was estimated to be $40,000 a year in 1902, it was clear that this practice could never be more than a very expensive hobby.

When Alfred did find himself in New York City he stayed at his fashionable apartment and rode one of his horses daily in Central Park. One day he spotted Agnes Ruiź, a striking young former Broadway showgirl who loved to ride. It is said that on the day they met her saddle had become loose and gallant Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt came to her assistance. The story may or may not be true, but what is true is that an affair quickly developed between the two.

A four-in-hand coach sets off from New York City, bound for Newport, Rhode Island, I the 1920 (Author’s collection)

Mary Agnes O’Brien Ruiź was born about 1880 into a modest household in St Louis, Missouri. She was reportedly a wild child. She married a rich Californian when she was a teenager. He soon died leaving the twenty-year-old widow, who went by Agnes, a modest inheritance. She moved to New York City to pursue her dream of becoming a showgirl. She was beautiful and soon caught the eye of Don Antonio Ruiź y Olivares, a wealthy Cuban who was serving as attaché in Washington, D.C. They married in August 1903. However, the marriage was not a happy one and within weeks they were living apart. Agnes received a substantial income from her husband and, like many well-to-do Americans at the time, had apartments in New York City and London.

By 1905 Elise and Alfred were spending less time together. She entertained at Oakland Farm and traveled frequently to Europe. He spent more and more time coaching and attending horse shows in the United States and Europe.

Exterior of the Barn at Vanderbilt’s Oakland Farm in Portsmouth, Rhode Island. The barn has two round towers on either side of the building (Providence Public Library Digital Collections)

Agnes Ruiź began to accompany Alfred to horse shows and to stay in his rail car. It soon became public gossip, and the public did not approve. Public opinion took Elise’s side, sympathizing with the abandoned wife bravely raising her son. By March 1908, Elsie Vanderbilt had had enough of Alfred’s affair and moved to the home of her wealthy brother in Tuxedo Park, New York. A lurid national scandal erupted in April after Elsie filed for divorce alleging adultery between Alfred and an unnamed mistress (Agnes Ruiź). Alfred made only a token objection to the divorce. Elsie was soon a free woman, with a $5 million trust fund for her young son.

Mary Agnes Ruiź, from a photo kept in Elise Vanderbilt’s 1908 divorce file that was sealed by statute for one hundred years (Author’s collection)

Later in 1908, to escape the American press, Alfred moved to a ten-bedroom flat in London. He set out to revive a commercial coaching route between London and Brighton. It took fifty-six horses to operate the line. Like his New York City to Philadelphia route, it never made any money.

Agnes Ruiź also travelled to London, where she and Alfred were often seen together. Back in the United States, Agnes’s husband began divorce proceedings, citing “misconduct with an ’unknown man.’” The aggrieved husband was granted a divorce and Agnes received a generous settlement. However, it soon became clear that Alfred would never marry his mistress. Tragically, the increasingly despondent Agnes committed suicide in her London apartment on May 19, 1909.

Even before Agnes died, Alfred Vanderbilt had already turned his attention to Margaret Mary Emerson McKim, a beautiful American divorcee and heir to her father’s Bromo-Seltzer fortune. Her wealth had allowed her to become part of New York society. In December 1902 she married her family’s physician, Dr. Smith H. McKim. It was not a happy marriage and eight years later Margaret divorced him in Reno, Nevada. She charged that Dr. McKim once beat her in a drunken rage. The divorce too became a national sensation. After the divorce was final in 1910, McKim threatened to sue Alfred for alienation of affection, a claim that could be pursued in court in those days. Dr. McKim ended up settling out of court with Alfred paying him $150,000.

On December 17, 1911, in the small English town of Reigate on the London to Brighton coach route, Margaret Emerson McKim became the second Mrs. Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt.

Alfred did have a decent eye for commercial real estate. In 1912 he built the magnificent Vanderbilt Hotel in New York City on the site of the Vanderbilt family home at Park Avenue and 34th Street, next to another of his projects, Grand Central Station. Alfred and Margaret made the hotel’s lavish two-story penthouse their New York City home (the former hotel is now office space and apartments).

Margaret learned from Elise’s mistake and rarely let Alfred out of her sight. Over the next three years they had two children: Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt Jr., a future businessman and racehorse breeder; and George Washington Vanderbilt III, who would become a noted yachtsman and scientific explorer.

Alfred continued his obsession with coaching and horses. In addition to the many horses at Oakland Farm, he kept about 60 of them in England. With the outbreak of World War One, the British government began confiscating horses for the war effort. Alfred did not object. In fact it appears he planned to donate a horse-drawn ambulance to the Red Cross and volunteer his services as its driver at the front.

On May 1, 1915, Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt and his valet Ronald Denyer boarded the RMS Lusitania, one of the most luxurious and comfortable ocean liners of the day, bound from New York City for England. With the war on, Margaret remained in New York City with the children. Six days later and within sight of Ireland, a German submarine torpedoed the huge ship, which sank in eighteen minutes. Alfred, who could not swim, gave his lifejacket to save a female passenger. Alfred and his valet were last seen helping women and children into life jackets and lifeboats.

More than a thousand people were lost, including Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt and his valet. Alfred was just 37. He had been head of the house of Vanderbilt for just over fifteen years. His body was never recovered.

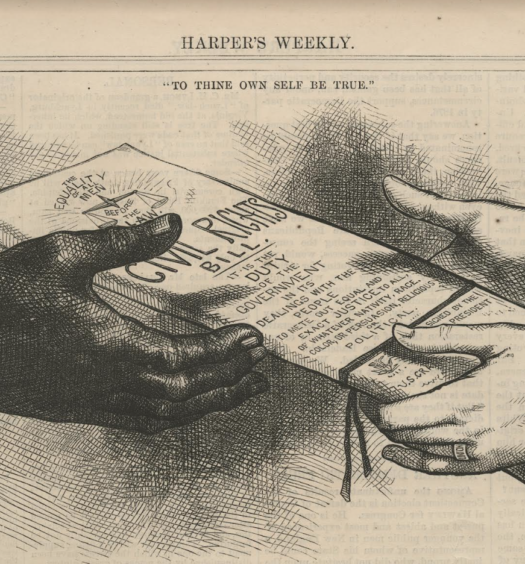

The YMCA

The Newport County Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) was established in 1878, in a Newport home on Mary Street built by former lieutenant governor Duncan C. Pell and his wife Anna. They were the great aunt and great uncle of future U.S. Senator Claiborne Pell.

By the turn of the century, the YMCA had outgrown the house and local board members wanted to build a new, modern YMCA building complete with an indoor pool. The idea was to attract young men to the YMCA as an alternative to the town’s “low theater, the dance hall, the saloon and the dive.” A committee was formed for this purpose.

Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt’s father, Cornelius II, devoted considerable time to charitable endeavors. He served on numerous non-profit boards and was a member of the executive committee of the International Young Men’s Christian Association. Alfred was also a benefactor of various philanthropies. Accordingly, it was only natural that the local committee approached Alfred seeking his assistance in building a new YMCA.

Alfred agreed to construct the building in memory of his father and donate it to the Newport YMCA. He hand-picked the architect, George S. Chappell of the New York firm of Erving & Chappell. Chappell worked closely with the Newport YMCA officials to design the building to meet their needs. Alfred retained Swallow & Howes, also of New York, as the contractor.

Postcard (circa 1913) of the YMCA building on Mary Street, built by Alfred Gwynn Vanderbilt in memory of his father and donated to the Newport YMCA in 1910 (Author’s collection)

The original YMCA structure was demolished and groundbreaking for the new building took place on August 31, 1908, three and a half months after Agnes’s suicide. Despite the recent scandal over his divorce, Alfred returned from London to be present when the cornerstone was laid on November 19, 1908. He soon returned to London.

On January 1, 1910, the new Mary Street YMCA, in attractive Colonial Revival style, was officially opened. Located on the south side of Mary Street, at the intersection of Clark Street, it included a lobby, an auditorium, a dining hall, classrooms, club rooms, dormitory rooms, and a pool in the basement.

Alfred was scheduled to depart New York City for an overseas trip in the first week of January, so he did not attend the elaborate ceremony for the building’s dedication. He did send, however, a letter that was read at the ceremony. The letter, dated December 22, 1909, was reprinted on the front page of the January 1, 1910 edition of the Newport Daily News. It stated, in part:

In lieu of my presence therefore I take pleasure in presenting to you the legal custodians of the property of the Young Men’s Christian Association in Newport, a building erected by me in fulfillment of my gift to the said association to have and to hold the same for the uses and purposes of the association in carrying on its religious and beneficent enterprises. My father’s zeal and unflagging interest in association work and welfare of young men has been to me in the erecting of this building in his memory a source of much gratification, and I feel if he were living, no act of mine would have given him more satisfaction or pleasure than to see the building in the city of Newport where he spent so many of his summers and was so well known to its citizens.

It is with this feeling therefore that I hope the interest of the people of Newport in the Association, now that they have a suitable building, will steadily increase and its influence upon boys and men of Newport and strangers within its gates will be an aid and a support to many in need and helpful in advancing generally the welfare of the community.

The president of the board of directors of the Newport YMCA formally accepted the building on behalf of the Newport YMCA and over 500 people donated a total of $24,500 to fund the completion of the building’s interior and furnish its rooms. It was a true community effort.

Coincidentally, just a year later, Newport’s second YMCA was built in downtown Newport just off Washington Square. Since the Civil War, the YMCA had provided for troop morale, entertainment, and religious services. A 1902 Act of Congress officially permitted the YMCA to erect and maintain “such buildings as their work for the promotion of the social and physical welfare of the garrison may require.”

The National YMCA received money to build a Newport military YMCA from a Cincinnati, Ohio, philanthropist, Mrs. Thomas J. Emery. The Newport Army and Navy YMCA was designed in the Beaux-Arts style and was the first cast concrete structure built in Newport. It is reported to be the first YMCA built under the 1902 act to serve both branches of the military.

The Aftermath

Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt had inherited nearly $43 million in 1899. When he died in 1915, he had managed to shrink the estate to just a little over $26 million.

Elsie Vanderbilt, Alfred’s first wife, married Naval officer Paul Fitzsimons in 1919. They resided at the Harborview estate in Newport opposite the Ida Lewis Yacht Club. Elise and Paul lived there quietly for the remainder of their lives. He died in 1946 and she in 1948. Harborview was sold in 1950, and the house was demolished for a residential subdivision.

Alfred’s second wife, Margaret, received $8,000,000 from Alfred’s estate and some of his property, including the luxury hotel in New York City and the 2,000-acre Sagamore Lodge in the Adirondacks (now Great Camp Sagamore). Their two sons also each received a substantial inheritance. Margaret moved from the Vanderbilt Hotel in New York City to Venfort Hall, a 47-room mansion in Lenox, Massachusetts. She married twice more, and both marriages ended in divorce. In 1931 she legally resumed her maiden name, Margaret Emerson. During World War II she was the Red Cross Director at Hickam Field in Hawaii. Her management experience, her daughter claimed, from supervising her twenty-plus household servants. She died in New York City on January 2, 1960.

The majority of Alfred Gwynn Vanderbilt’s estate went to his first son by Elise, William Henry Vanderbilt III. Although he was born in New York City, William spent much of his life in Rhode Island. He attended St. George’s School in Middletown, Rhode Island, but dropped out in 1917 out at age fifteen to join the U.S. Naval Coast Defense Reserve. As he was only fifteen at the time, he was one of the youngest Americans to have served in the war. From June 1, 1917, to March 7, 1918, he was stationed at the Newport Naval Torpedo Station.

He was discharged from the Navy at age eighteen and joined the Naval Reserve. When he turned 21 he inherited a $5 million trust fund his father had set up when he and Elise divorced. William had also inherited Oakland Farm in 1915.

William Henry Vanderbilt III married Emily O’Neill Davies in 1923. The following summer, he and Emily threw a ball for 500 guests at Oakland Farm.

In 1925, William started The Short Line bus company, operating between Newport and Providence. The bus company expanded and was sold in 1955. After being acquired several more times, today it operates as part of Peter Pan Bus Lines.

William was one of the few Vanderbilts to take an interest in politics. In 1928 he was elected to the Rhode Island State Senate. He fought for the Mount Hope Bridge that connects Aquidneck Island with the mainland and was named chairman of the Mount Hope Bridge Commission. He gave the opening address at the bridge’s dedication in 1929. He successfully ran for Governor of Rhode Island in 1938, but he lost a re-election bid in 1940.

In early 1941, William Vanderbilt was recalled to active duty with the rank of Lieutenant Commander (his two half-brothers also served in the Navy during World War II). He was assigned as executive officer with the Special Operations Branch of the Office of Strategic Services (the basis for the modern Central Intelligence Agency) under General William (“Wild Bill”) Donovan. In May 1944, he was assigned to the staff of Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, commander in chief of the Pacific Fleet. Promoted to the rank of captain prior to the end of the war, after his discharge he retired to a farm in Williamstown, Massachusetts.

William Henry Vanderbilt III was married three times and had a total of four children. He died in 1981 at the age of 79. In an obituary Time magazine described him as a “farmer-philanthropist and sometime politician.”

Alfred Gwynn Vanderbilt’s beloved Oakland Farm, reduced over time to just 150-acres, was sold by William in 1947. The huge horse ring was long gone, demolished in 1937 when it became too difficult to maintain and insure. The sprawling stables were demolished in 1948, and the timber was used to construct five houses in Portsmouth. The main house was heavily damaged by storms and had to be torn down in 1949. The cattle barn followed in 1960. The farm then sat vacant until 1984, when it was sold to the Regine family who developed Oakland Farm Condominiums. The farm’s original white wooden gate can still be seen on the west side of East Main Road, just south of Oakland Farm Drive.

Newport had two YMCAs until 1973 when the Navy relocated the Seventh Fleet out of Newport. This led to the closing of the Army and Navy YMCA in 1973. The building remained vacant for a number of years. It was sold in 1988 to a consortium of private non-profit organizations who converted it into housing for the needy.

The Mary Street YMCA remined in operation until 1974, when the Newport County YMCA moved to a new building in Middletown, Rhode Island. The Mary Street building was sold to Doris Duke’s Newport Restoration Foundation for use as a woodworking/carpentry shop. It was sold by the Newport Restoration Foundation in 1995 for conversion into a hotel, after which a large wing was added. The structures now comprise a posh hotel called The Vanderbilt. Its interior is decorated to imitate the lavish rooms of Newport’s Gilded Age mansions.

Notes on Sources

Considering Alfred Gwynn Vanderbilt’s position as the head of the Vanderbilt family and Chairman of the New York Central Railroad it is surprising how little has been written about him. I previously mentioned brief references to him found in The Vanderbilts and Fortune’s Children: The Fall of the House of Vanderbilt (William Morrow, 1989) by Arthur T. Vanderbilt II. The only book to focus on Alfred, Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt: The Unlikely Hero of the Lusitania (Hamilton Books, 2013), by Steven H. Gittelman and Emily Gittelman, relies almost exclusively on divorce transcripts and contemporary newspaper stories. Newspapers of the time were, however, more interested in sensational stories than historical accuracy. There is also a decent Wikipedia page on Alfred, at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alfred_Gwynne_Vanderbilt.

The AIA Guide to Newport by Ronald J. Onorato is an invaluable resource for information on all notable buildings in Newport, including both the Mary Street YMCA and the Newport Army and Navy YMCA. Another useful source is James L. Yarnell, Newport Through Its Architecture, A History of Styles from Postmedieval to Postmodern (University Press of New England, 2005), pages 170-71. The Newport Daily News’s January 1, 1910 edition had important information relating to the opening ceremony of the YMCA building. The Newport Historical Society also has a wealth of information and photographs documenting the Mary Street YMCA.

The Oakland Farm Condominium Association has published a short, illustrated history of the Vanderbilt farm accessible at www.premierpm.biz/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/OaklandFarmHistory-v2.pdf.

The Newport Preservation Society will be continuing its Weekend of Coaching event on the weekend of August 19-21, 2022. There will be coaching drives each day, and an exhibition on the Whips at The Breakers on August 20, 2022. For more information, go to https://www.newportmansions.org/events/a-weekend-of-coaching.