Note: This article is the second in a two-part series on the career of civil rights reformer George Downing. Readers can access Part I at https://smallstatebighistory.com/george-t-downing-and-the-black-convention-movement/

My self-respect revolts at the idea of asking any man, white or colored, to open the door of his mansion to me … I asked that the legal recognition of my civil rights shall be asserted affirmatively by national legislation, because the negation of a principle is the first step towards its final overthrow … In this case, as in the case of slavery, as in the case of the war for the preservation of the Union, the cause of humanity is the cause of the nation. (George T. Downing quoted in the February 27, 1875 edition of the New York Tribune).

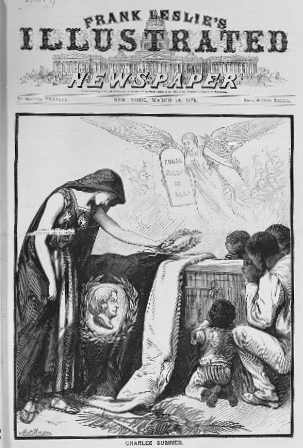

In the winter of 1874, the veteran Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner (1811 – 1874) spent his final days thinking of little else than the landmark civil rights bill that was meandering its way through Congress. With his health rapidly deteriorating, Sumner struggled to fulfill his duties in the Senate. He had difficulty getting from his home in Washington, D.C., to the Senate chambers but he was determined to take the fight over civil rights, despite numerous legislative setbacks over a four-year period, to the very end.

In attendance at Sumner’s bedside were the prominent Black leaders Frederick Douglass, James Wormley, and Rhode Islander George Downing, all veterans of state and national campaigns to demand constitutional rights for African Americans. The promise of a new birth of freedom during the Civil War (1861-1865) sparked not only an intense drive for meaningful measures of freedom in the South for newly emancipated slaves but also for hundreds of thousands of African Americans living in the North. At issue was the protection of liberty and freedom and a broad measure of equality for aspects of social life. George Downing saw the changes wrought by the Civil War, a “new order of things” as he put it, leading to the enshrining of the language of liberty in the Declaration of Independence in the American constitutional order.[1]

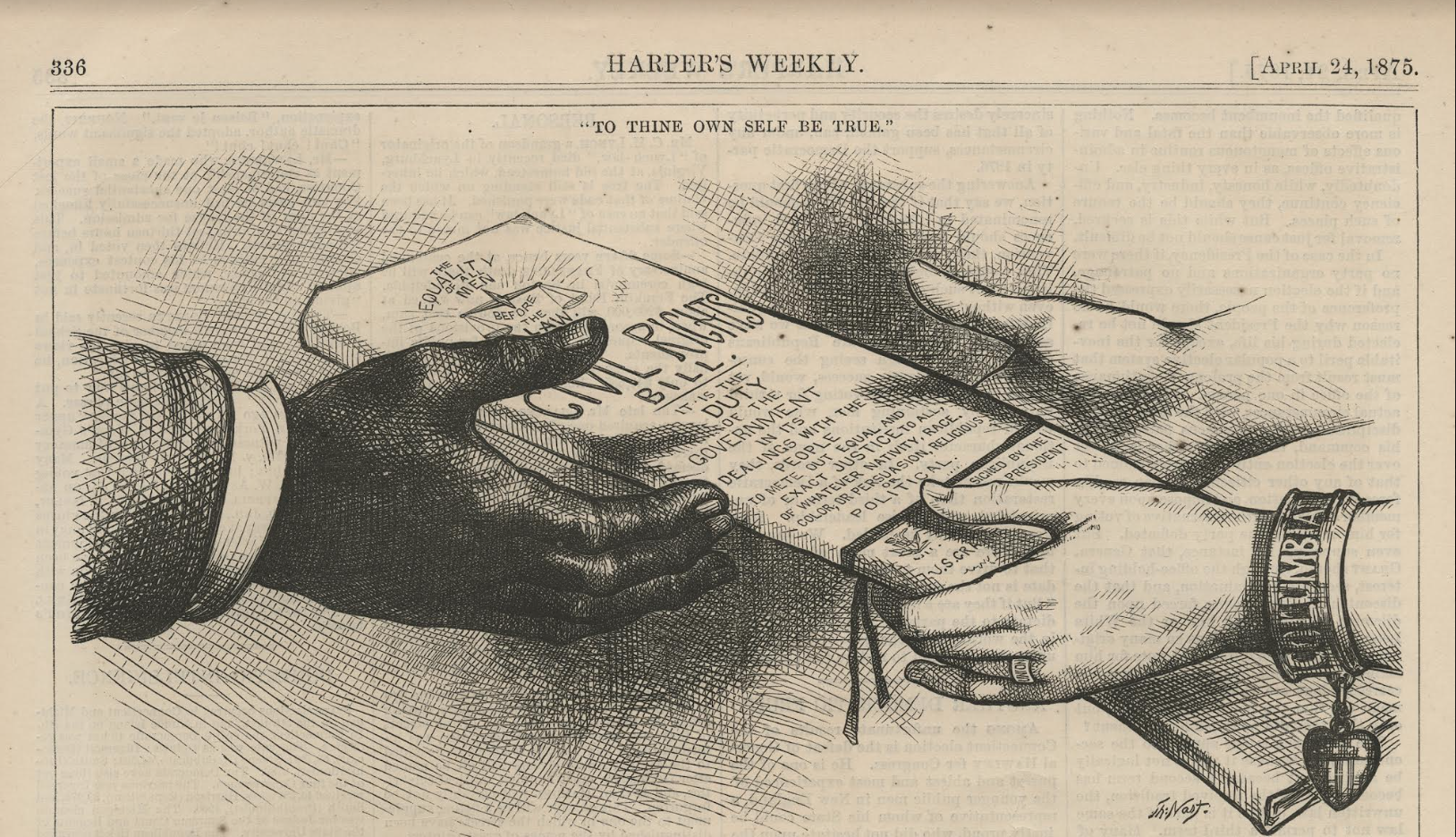

Sumner’s Civil Rights Bill was first introduced in early 1870. His goal was to enact legislation pursuant to the 14th Amendment to abolish de jure segregation in public schools, hotels and restaurants, and other common carriers. The bill was designed to prohibit discrimination by railroads, steamboats, public conveyances, hotels, restaurants, licensed theaters, public schools, juries, and church organizations or cemetery associations “incorporated by national or State authority.”[2] Sumner and John Mercer Langston, a close associate of Downing’s, co-authored the bill.[3] It was grounded in the 13th and 14th Amendments and was a supplement to the 1866 Civil Rights Acts, which entitled all citizens of the U.S. to rights of contract, property, security of the person, and equality before the law.[4] To the former slave John Roy Lynch, who was elected to Congress from Mississippi, Sumner’s bill “has for its object the protection of human rights.”[5]

The Reconstruction Amendments transformed the original Constitution from a document concerned with the relationship between the federal government and the states to a document through which minorities could make a claim to a robust and substantive definition of freedom.[6] As historian Christopher Bonner has noted, Black Americans “wanted the expansive, active federal government of the Civil War years to survive” following the negotiated armistice in the spring of 1865 and “implement a robust set of legal protections for citizens.”[7] At the New England Colored Convention held in Boston in December 1865, George Downing authored a resolution calling for equality before the law for all Americans without regard to color to be the guiding sentiment of the land [8] Despite profound opposition to civil rights in both the North and the South, Downing continued to hold on to his belief in what he labeled the “special mission” of the United States. African Americans were to play a special, almost providential role, in “America’s mission.”[9]

Mourning Charles Sumner, cover of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, March 28, 1874 (Library of Congress)

For Downing, the Reconstruction period was a direct extension of the issues over which the Civil War was fought. Though no African Americans sat in Congress when the transformative Amendments were drafted, the constitutional revolution that emerged between 1865-1870 stemmed from a decades-long debate about the nature of American democracy within Black abolitionist circles. Meeting in conventions as early as 1831, Black leaders pushed for a fundamental transformation of the American democratic order, especially for civil and suffrage rights.[10] This emergent African-American constitutionalism helped to shape the debate over the role of the government in protecting civil and political rights in the post-Civil War era.[11]

In the 1870s, in Downing’s Newport, Black citizens expressed the hope “that every member of Congress will interest himself in our behalf for rights and justice … hoping that they may be true and just to an ever loyal people, and not withhold from us such protection as will protect us in our civil rights before the law; that by passing such laws it affects the rights of nearly 1 million legal voters in the United States whose rights are not ignored.”[12] All “possible help is needed to secure the passage of the Bill for Equal Rights,” implored Sumner in a private letter to his friend Downing. Besides “petitions and letters there must be a strong committee to visit every Republican Senator. Not a vote must be lost.”[13]

For decades, Sumner had worked tirelessly to destroy slavery, the southern Slave Power, and the concomitant evil of racism in American society. The committed abolitionist was nearly beaten to death in 1856 by the proslavery southerner Preston Brooks, a U.S. Representative from South Carolina.[14] After a prolonged and painful recovery, Sumner resumed his full-time duties in the Senate in 1859 and became a trailblazing legislator. Never one to follow the party line, Sumner often stood against a powerful segment within the Republican Party that adhered to the belief that legislation that benefited African Americans encouraged dependency rather than adherence to free labor principles. Opponents of Sumner’s civil rights bill denied that the right to serve on a jury, attend a public school, or be afforded equal treatment and protection by a private business was protected by the 14th Amendment.[15] In addition, the devastating financial panic that gripped the nation in 1873 shifted attention away from civil rights.

While the 14th and 15th Amendments, ratified in 1868 and 1870 respectively, codified birth-right citizenship and Black voting, the amendments did not lead to a broader measure of racial egalitarianism. In in his paper, the New National Era, Frederick Douglass proclaimed that “the black man is not a free American citizen in the sense that a white man is a free American citizen; he cannot protect himself against encroachments upon the rights and privileges already allowed him in a court of justice without an impartial jury.”[16] The “press, platform, pulpit should continue to direct their energies to the removal of the hardships and wrongs which continue to be the lot of the colored people … because they wear a complexion which two hundred and fifty years of slavery taught the great mass of the American people to hate, and which the fifteenth amendment has not yet taught the American people to love.”[17]

In late December 1869, four years after the Confederate surrender at Appomattox, Downing played a pivotal role in the creation of a National Executive Committee of Colored Persons. The committee grew out of the largest and most widely noticed Black convention of the 19th century held in the nation’s capital at the end of the year. In an effort to accomplish their goals, Downing and other Black leaders met with Congressional Republicans, as well as with President Ulysses S. Grant. Downing was the key lobbyist for Sumner’s bill, serving as the head of what became known as the national civil rights council.[18]

Building on a charge from Sumner, Downing issued a call for African Americans to “organize” in order for collective “power to be properly felt.”[19] Sumner told Downing, one of his closest friends, that “Equal Rights” in the United States “must be recognized & accepted by all.”[20] The way to accomplish this was through the strong arm of the federal government. The most important and controversial question raised by Sumner’s proposed legislation was the constitutionality of de jure segregation of public schools, a topic Downing was well-versed in.[21] Though a Newport resident, Downing’s children were educated in Massachusetts because Newport’s schools remained segregated until the 1860s. Downing wanted a “national system of education” open to all Americans.[22]

Downing firmly believed, as he proclaimed in New Orleans at a national Black convention in 1872, that the “federal government” was “bound to protect” all citizens by “guaranteeing to every State a republican form of government, as required by article four of the constitution.”[23] On the floor of the Senate, Sumner drew from Downing’s understanding of the powers of the federal government under the Constitution. “I conclude that when the supreme law says of right a thing shall not be, Congress, which has that supreme law as its guide and authority, has the power to enforce the same.”[24] A “man’s private domicile is his own castle,” declared Downing. “But the public inn, the public or common school, the public place of amusement, as well as common carriers, asking the special protection of law, created through its action on the pleas and for the benefit of the public good, have no such exclusive right as the citizen may rightfully claim within his home.”[25]

In 1873, Downing served as the acting president of the National Civil Rights Convention, which met in Washington, D.C., from December 9-12. Downing took over after P.B.S. Pinchback, who briefly served as governor of Louisiana, had to leave in order to attend to business in the Senate.[26] With Sumner’s civil rights bill still floundering, the meeting was called to discuss “non-recognition” of the rights of Black Americans as concerned the “public privileges” connected to American citizenship.[27] On the second day, Douglass put forth a resolution calling on Congress to “enact into law a measure that will, so far as law is considered, protect all classes of citizens … without distinction to race or color.”[28] Delegates to the convention traveled from as far away as California.[29] On the final day of the convention, Downing led a delegation to meet with President Grant in the White House. They implored Grant to assist them in asking Congress for “relief.”

Grant, unlike his predecessor Andrew Johnson, cordially received the Black delegation. The president acknowledged the “existing prejudices” and promised to speak to congressional leaders about the pending civil rights bill.[30] Downing had a solid working relationship with Grant, extolling the president at one point for the appointment of significant “numbers” of African Americans to “important positions” and giving “a rebuke to vulgar prejudices against a class.”[31] At the convention, Downing read a “declaration of principles” which was designed to demonstrate the power granted to Congress under the 14th Amendment to enforce the “privileges and immunities” of citizenship, along with “equal rights” against the states. As the principal author of a memorial sent to Congress relating to civil rights, Downing boldly proclaimed that it was the “imperative duty of the Government” to “protect” civil rights by a “national law.”[32]

Just before he breathed his last in March 1874, with Downing close by, Sumner said, “You must take care of the civil-rights bill, my bill, the civil-rights bill, don’t let it fail.”[33] In February 1875, in a petition to the Senate Judiciary Committee, Downing and John Mercer Langston emphatically called for the retention of provisions relating to schools. “We ask that the schools established by your legislation be a common school, one to which the children of American parents, without regard to color and nationality and without regard to religion and pecuniary circumstances may go and enjoy the largest advantages of education – and education which is in fact American!” [34] A month later, Sumner’s bill, minus important provisions regarding schools, churches, and cemeteries, passed Congress on February 27, 1875. Democrats were unanimous in their opposition.[35]

Ultimately, Congress passed a much watered-down version of Sumner’s original bill, making racial discrimination in “inns, public conveyances … and other places of public amusement,” along with the selection of juries, a federal crime. However, the school provision, something that mattered deeply to Downing and Langston, was removed. As Kate Masur has argued, “congressional Republicans’ lack of commitment to the bill, and particularly to the school integration clause, fed African Americans’ growing frustrations with the party and fostered continuing discussions about the possibility of defections.”[36]

A year and a half after passage of the act, Downing along with other prominent Newport abolitionists, including Rev. Mahlon Van Horne, Henry Jeter and Benjamin Burton, wrote to famed Boston abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison in utter despair at the “indifference” Republicans were demonstrating to civil rights. Downing and his colleagues were “sick at heart” from “hope deferred.”[37] As historian Heather Cox Richardson notes in her landmark work, The Death of Reconstruction, by 1874, most Republicans “were ready to cut” ties with African Americans in the North and the South “in order to force” Blacks to “fall back on their own resources and to protect the government from the machinations of demagogues pushing special-interest legislation.”[38]

As the 1880s ushered in a new generation of Republicans into office, most of whom did not subscribe to the same thinking of the radical Republicans of the previous decade, Black voters began to feel abandoned. Downing recognized the shift in the Republican agenda and called for a statewide convention of colored men to meet in Newport in October 1882. Unlike the Newport convention of 1869 that sought labor rights, this convention focused on independent political action. The convention felt that the colored voter “ought not to follow blindly in the political track of the Republican party, but ought to think and act for themselves, and be guided rather by an intelligent observation of the present and care for the future than by sentimental memories of the past.”[39] Downing recognized the shift in Republican support and looked to re-align the political thinking of Black Rhode Islanders.

During the presidential race of 1884 the Republican candidate James Blaine faced off against Grover Cleveland. “Mr. Downing refused to support Mr. Blaine [and] believed that the Republican Party had proven faithless to the colored people and that neither the party nor its unfortunate candidate was worthy of the suffrage of the former unflinching and unfailing colored allies, he had come to feel that the Democratic party of today was not what it was twenty-five years ago. After the Republican Supreme Court decision declared Civil Rights legislation null and void he conferred personally and in some cases by letter, with leading Democrats in New Jersey, Connecticut and Ohio and found them ready to accord equal and exact justice to all men. He found the Democrats voting for and passing laws for the enforcement of Civil Rights. It was no difficult thing for him to oppose Blaine.”[40]

Downing’s worst fears came to pass in 1883 when the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the 1875 Civil Rights Act. Justice Joseph Bradley held that the public accommodations provisions of Sumner’s bill were unconstitutional. Bradley outright rejected the 14h Amendment as a basis for enforcement. Civil rights secured by the 14th Amendment could not be deprived by private action, and Congress lacked the power to reverse such acts.[41]. Coupled with another decision in 1873 (Slaughterhouse Cases), the state-action doctrine, so much feared by Downing and other Black leaders, enabled the rise of statutory Jim Crow laws.[41]

In 1885, after the Supreme Court’s decision in the Civil Rights Cases, Downing’s activism, coupled with that of his Newport colleague, the Rev. Mahlon Van Horne, led to the passage of a Rhode Island statute that declared that “no person within the jurisdiction of this state shall be debarred from the full and equal enjoyment of the accommodations, advantages, facilities and privileges of any licensed inns, public conveyances, on land or water, or from any licensed places of public amusement, on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” That same year, Reverend Van Horne became the first African American elected to the Rhode Island General Assembly. In 1898, the Sumner Political Club named in honor of Charles Sumner was organized by Downing, Van Horne and others, in order to combat the growing tide of racism that was gripping the country [42]. The lynchings of African Americans in great numbers in the South at the end of the nineteenth century was cause for great concern for Downing and foreshadowed a delay of the promise for equality that he so hoped to create.[43] He fought tirelessly all his adult life for equal rights and equal justice for his race and while he did not see the fruition for all his works he did accomplish much. He died at Newport on July 21, 1903.

George T. Downing and Family surrounded by their family heirlooms and memorabilia (DeGrasse-Howard photographs, Massachusetts Historical Society)

Notes:

[1] See Downing’s important 1874 essay in The Independent at https://ia904608.us.archive.org/7/items/sim_independent_1874-02-26_26_1317/sim_independent_1874-02-26_26_1317.pdf (see pp.1-2) [2] See Senate Historical Office, “Charles Sumner: After the Caning,” Senate Stories (May 4, 2020) at https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/senate-stories/charles-sumner-after-the-caning.htm#5 [3] Hugh Davis, “We Will Be Satisfied with Nothing Less”: The African American Struggle for Equal Rights During Reconstruction (Cornell University Press, 2011), 59. See also Langston’s landmark 1866 speech on “equality before the law” at https://www.loc.gov/resource/rbaapc.15500/?st=gallery and Erik Chaput’s article on Langston’s civil rights activism in Ohio at http://commonplace.online/article/teaching-antislavery-constitutionalism/ [4] See Amy Dru Stanley’s insightful essay “Slave Emancipation and the Revolutionizing of Human Rights,” in Kate Masur and Gregory Downs, eds., The World the Civil War Made (University of North Carolina Press, 2015), 269-272. [5] Congressional Globe, 43rd, 2nd sess (1875), 947. [6] Eric Foner, The Story of American Freedom (W.W. Norton, 1998), 107. See also Eric Foner, “Rights and the Constitution in Black Life During the Civil War and Reconstruction,” Journal of American History (December 1987), 880. [7] Christopher Bonner, Remaking the Republic: Black Politics and the Creation of American Citizenship (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020), 150. [8] Accessed here at https://omeka.coloredconventions.org/items/show/590 [9] New York Times, November 23, 1877. [10] See Kate Masur, Until Justice Be Done (W.W. Norton, 2020). Erik Chaput reviewed Masur’s book on June 6, 2021 for the Providence Journal. See also the landmark Colored Convention Project website at https://coloredconventions.org/ [11] See Xi Wang, The Trial of Democracy: Black Suffrage and Northern Republicans, 1860-1910 (University of Georgia Press, 1997). [12] Meeting of African American leaders in Newport, Rhode Island reported in the Congressional Globe, Senate, 42nd Congress, 2nd Session, 1872 at https://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=llcg&fileName=101/llcg101.db&recNum=434 [13] Quoted in David Herbert Donald, Charles Sumner (De Capo Press, 1996), 536. Donald’s multi-volume work remains the definitive biography of Sumner. While originally published in 1960 and 1970, in 1996, a combined edition was created. [14] Manisha Sinha, “The Caning of Charles Sumner: Slavery, Race, and Ideology in the Age of the Civil War,” Journal of the Early Republic 23:2 (2003), 233–62. See also Sinha’s magisterial account of the abolitionist movement, The Slave’s Cause (Yale University Press, 2017). [15] The most thorough discussion of education and the Civil Rights Act of 1875 can be found in legal scholar Michael McConnell’s “Originalism and the Desegregation Decisions,” Virginia Law Review 81:4 (1985), 947-1140. [16] The New National Era, December 5, 1872, which can be accessed here: https://rbscp.lib.rochester.edu/4392 [17] The New National Era, May 26, 1870. [18] Kate Masur, An Example for All the Land (University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 181. [19] Daily National Republican (Washington), January 21, 1874. See Sumner to Downing, December 28, 1871 in the Abolitionists Papers (1855 – 1872) at Roger Williams University. [20] Sumner to Downing, April 8, 1872. The letter is contained in the Abolitionists Papers (1855 – 1872) located at Roger Williams University library and can be viewed here. [21] See Erik Chaput and Russell DeSimone’s article for Small State on school desegregation in Rhode Island: http://smallstatebighistory.com/end-school-desegregation-rhode-island/ [22] Daily National Republican (Washington), January 27, 1874. [23] For more on the 1872 convention in New Orleans see https://omeka.coloredconventions.org/items/show/544. Frederick Douglass served as the president of the convention while Downing served as one of its vice presidents. [24] Sumner quoting Downing January 1872. See page 283-284 of volume 19 of the Sumner Papers at https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/50386/pg50386-images.html [25] Downing quoted in Masur, An Example for all the Land, 227. [26] For more on Pinchback see this engaging essay by Henry Louis Gates, Jr., see https://www.pbs.org/wnet/african-americans-many-rivers-to-cross/history/the-black-governor-who-was-almost-a-senator/ [27] See the summary contained in the published pamphlet from the convention on Google Books here. [28] Pacific Appeal, December 27, 1873. See also New National Era, December 18, 1873. [29] Elevator, December 27, 1873. See also Pacific Appeal, December 27, 1873 and January 3, 1874. The Pacific Appeal newspaper can be accessed here. [30] Elevator, December 27, 1873. [31] Quoted in Ron Chernow, Grant (Penguin, 2017), 642. [32] The full memorial can be accessed from Google Books. [33] See: https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/generic/CivilRightsAct1875.htm [34] Pacific Appeal, February 6, 1875. [35] See Eric Foner, The Second Founding: How the Civil War and Reconstruction Remade the Constitution (W.W. Norton, 2019), 143-144. [36] Masur, An Example for All the Land, 228. [37] The letter dated December 5, 1876 is part of the massive Antislavery Collection at the Boston Public Library. A digitized version can be found here: https://www.digitalcommonwealth.org/search/commonwealth:dv143185t [38] Heather Cox Richardson, The Death of Reconstruction (Harvard University Press, 2001), 140. Richardson argues that issues of economic class, along with race, were critical in terms of the end of Reconstruction. Northern support for the rights of African Americans weakened as growing labor interests critiqued the new industrial economy. [39] The Providence Evening Telegram, October 19, 1882. [40] S.A.M. Washington, George Thomas Downing – Sketch of His Life and Times (The Milne Printery, 1910), 18-19. [41] See Downing’s 1876 letter to Garrison at https://www.digitalcommonwealth.org/book_viewer/commonwealth:dv143185t; See also Eric Foner, “The Supreme Court and the History of Reconstruction,” Columbia Law Review 112:7 (2012): 1585–1606. [42] See Geralyn Ducady’s informative essay on civil rights in Rhode Island from the late 19th century to the 1960s at https://library.providence.edu/encompass/african-american-civil-rights-in-rhode-island/african-american-civil-rights-in-rhode-island/ [43] Boston Herald, October 17, 1895. See also Amy Wood, Lynching and Spectacle: Witnessing Racial Violence in America, 1890-1940 (University of North Carolina Press, 2011).