We rejoice that we are thrown into a revolution where the contest is not for landed territory, but for freedom; the weapons not carnal, but spiritual; where struggles are not for blood, but for right; and where the bow is the power of God, and the arrow the instrument of divine justice (Minutes of the Fourth Annual Convention for the Improvement of the Free People of Color in the United States, 1834)

In early January 1831, prominent leaders in the Black community in Providence, including Alfred Niger, a barber, along with laborer George Willis and trader George McCarty, convened in the African Union Meeting House and authored a lengthy petition to the General Assembly challenging the state’s taxation and voting structure. Highlighting the “industrious and economical habits” of the state’s growing free Black population that had acquired numerous “freeholds,” the petitioners protested against the collection of property taxes, “while the same authority by which the taxes were attempted to be justified denies to them the privileges and immunities common to all other freeholders in the state.”[1] In making a “privilege and immunities” argument, the petitioners were relying on the U.S. Constitution.

Northern Black leaders railed against “oppressive treatment” and to the systematic “prejudices” as clear violations of the tenements of the language of equality embedded in the Declaration of Independence and a mockery of the steadfast commitment of African Americans to the Patriot cause both in the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812.[2] With Providence beset by multiple race riots in 1824 and 1831, African Americans challenged “unconstitutional and unjust” laws and the “dark clouds of prejudice” that beset their communities.[3] Black Rhode Islanders had been disenfranchised in 1822 by an enactment of the General Assembly and experienced school segregation in Bristol, Newport and Providence, where their children were denied schooling beyond the grade school level.

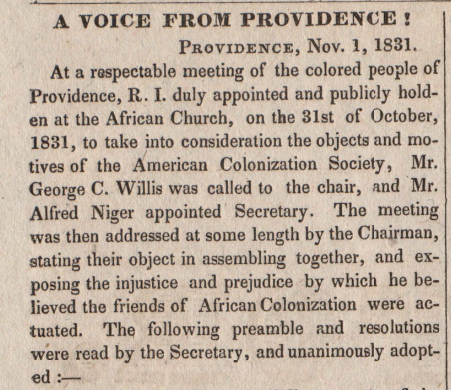

An excerpt from an article in the Liberator, mentioning the roles of Providence Black Leaders George Wyllis and Alfred Niger at a meeting of the American Colonization Society (Russell J. DeSimone Collection)

In the petitioners’ view the right of taxation necessarily involved the “corresponding right of suffrage and representation,” along with funding for expanded public schools to include African American students. The present situation in Rhode Island involved the “denial of equal rights” to the state’s Black citizens. Rather than entertain the possibility of Black voting and education, the General Assembly, then meeting in rotation in the town of East Greenwich, just a few days after receiving the petition, resolved the matter by voting to exempt the Black population from taxation. The Assembly did not accept the petitioners’ understanding of the boundaries of citizenship.[4] It would take another decade and political strife before Blacks were permitted to vote in state elections.

Connected not only with other leaders within Rhode Island, Niger, Willis, and McCarty, were also part of an emerging national Black convention movement whose aim was to stem the growing tide of northern racist laws that were a hallmark of the Jacksonian period.[5] Black leaders began to speak of forming national organizations to protest racial injustice and the Black convention movement provided a formal mechanism to attack the twin evils of slavery and racism.[6] The method to attain a redress of grievances was to petition Congress and state legislatures—just as Niger, Willis and McCarty had done—“to be admitted to the rights and privileges of American citizens.”[7] The advent of the doctrine of immediate abolition of slavery in the South in the 1830s, as distinguished from an earlier period of abolition in the wake of the American Revolution in the North, now meant a call for social justice for all Blacks, slaves as well as free.

Historical scholarship over the last 30 years has shed significant light on the activities of abolitionists in Rhode Island from the post-Revolutionary period through the middle of the 1830s. We have learned a great deal from the scholarship of Deborah Van Broekhoven and John Myers, for example, on the anti-slavery networks in Rhode Island, and most recently from the scholarship of historian CJ Martin.[8]

Black Rhode Islanders took part in a movement to challenge the “unjust and unconstitutional laws” enacted in the North against the “free people of color” and to use the power of petition to challenge the racial status quo.[9] As stated by prominent New York abolitionist William Hamilton, one of the founders of Freedom’s Journal (the first Black newspaper formed in the United States), the convention movement was “highly necessary” for the “free people of color” in order to “combine and closely attend to their own particular interest.”[10]

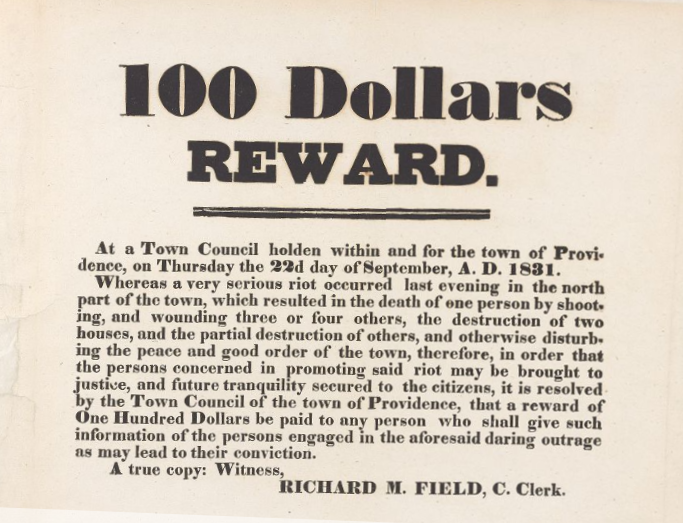

Reward offered for the identity of the perpetrators of the Providence race riot in 1831 (courtesy of Brown University Library)

The Black convention movement spanned the entirety of the 19th century with the initial stages commencing in the aftermath of significant racial violence in the North in the late 1820s. The first meeting in Philadelphia, which included a contingent from Providence, Rhode Island, arose in reaction to a move by white leaders in Cincinnati to remove the Black population after a dispute emerged over job competition with whites. The ensuing race riot in Cincinnati in 1829 led Black leaders in the northeast and Midwest to organize to protest against white-on-Black violence, racial discrimination, and slavery in the South.[11]

Following Cincinnati’s enforcement of the state “Black laws” and the subsequent Black violence unleashed by mobs in the city, a Baltimore activist appealed to African American leaders throughout the North to devise a plan for emigration to Canada.[12] This was a new plan somewhat distinct from a “Back to Africa” movement in the early 1820s. For free Black leaders, including Paul Cuffee, Richard Allen and James Forten, removal to Africa was grounded in the notion that endemic racism in the United States was simply too powerful to overcome.[13] The vast majority of Black leaders, however, came to reject this idea.

The 1829 appeal went unanswered for several months until the Reverend Richard Allen of Mother Bethel A.M.E. Church in Philadelphia called a national meeting of Black leaders to address the issue.[14] Delegations from primarily northern free states (though the upper slave states of Maryland, Delaware and Virginia were also in attendance) met at the Bethel Church on September 20, 1830, and after an “appropriate prayer by the venerable Bishop Allen,” the convention was organized. Allen served as president. George Willis and Alfred Niger represented Rhode Island. The meeting launched a movement, an “evolving crusade for Black freedom,” according to historian David Blight.[15] In addition to the first gathering in 1830, Philadelphia hosted the conventions in 1831, 1832, 1833, 1834, and 1835.[16]

On the agenda in 1830 were topics including, education and self-help, emigration plans to Canada, and opposition to the ideology of the white-led American Colonization Society.[17] As “long at least as the Colonization Society exists, will a Convention of colored people be highly necessary,” argued William Hamilton.[18] Just a year before, a group of free Blacks from Cincinnati set up a voluntary settlement in Ontario, Canada. They were later joined by African Americans from New York and Massachusetts. The settlement was named after British abolitionist William Wilberforce. Reaction to the conservative, white-led American Colonization Society was fierce and would serve as the driving force behind the rise of an abolitionist movement determined to end slavery and racism not through emigration out of the United States, but through a fundamental reform of the United States so as to extended full civil and political rights to both Black and white Americans.[19]

The challenge was, however, daunting. The establishment of schools and avenues for economic independence, which in turn would lead to a political culture of respectability and racial uplift, were part of the method Black leaders adopted to combat the growing tide of northern racism. Black leaders in this period generally desired assimilation into a white-led society and they believed that a demonstration of respectability was critical in this endeavor. “Be righteous, be honest, be just, be economical, be prudent, offend not the laws of your country—in a word, live in that purity of life, by both precept and example.”[20] There was an intense concern with self-image and social behavior, leading to the creation of such organizations as the American Moral Reform Society, which had James Forten of Philadelphia as president.[21]

According to historian Van Gosse, the “politics of deference remained in place, enforced by those who believed that any abolitionist agitation by black Americans invited physical assault, and convinced that the mass of free people of color lacked republican virtues.”[22] Northern Blacks were often viewed by whites as posing an economic threat, along with creating a burden for state and local poor relief agencies, and as a source of crime.[23] On the convention floor, Black men tried to counter this as they “debated the future of Black America, and that conversation became the principal agency for Black activism from 1830 up to the Civil War,” according to Princeton University historian Eddie Glaude.[24]

Richard Allen, a minister from Philadelphia who was a leader of the Black Convention movement (New York Public Library Digital Collections)

Though the prominence of Philadelphia’s Black leaders was on full display in 1830, Richard Allen advocated mass emigration to Canada. Early on a call was made for the formation of auxiliary societies, along with the appointment of an agent to live in “Upper Canada” with the purpose to purchase land for emigration settlements in the near future, settlements made of the “well regulated” northern Black communities and free of the “invidious distinction of color” and where Blacks would be “entitled to all the rights, privileges, and immunities of other citizens.” Voluntary Black emigration to Canada, controlled by Great Britain, a nation that would abolish slavery in its colonies in just a few years, was distinct from the efforts of the American Colonization Society. Allen railed against this white-led organization formed in 1816. “However great the debt which these United States may owe to injured Africa, and however unjustly her sons have been made to bleed, and her daughters to drink of the cup of affliction, still we who have been born and nurtured on this soil, we, whose habits, manners, and customs are the same in common with other Americans, can never consent to take our lives in our hands, and be the bearers of the redress offered by that Society to that much afflicted country,” maintained Allen in his keynote address.[25]

A new society, “The American Society of Free Persons of Color” was to be formed with the express purpose of “purchasing land for the establishment of a settlement” in Canada” and shall consist of “such Persons of Color as shall pay not less than twenty-five cents.” The society was also to work towards the improvement of the “moral,” “independent,” and “political standing” of free African Americans through the development of “agricultural and mechanical arts” and the “sciences.” [26]

In Philadelphia in June of 1831, in what was billed as the first official “First Colored Convention,” Black leaders met this time at the Wesleyan Church. The majority of the 1830 convention attendees, as the editors of the enormously valuable Colored Convention Project website note, were made up of individuals who were not actively involved in what would eventually become the Colored Conventions movement commencing in 1831.[27] John Bowers, an active member of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society, served as president of this convention, with Rhode Islanders George Willis serving as a vice-president and Alfred Niger as a corresponding secretary.[28]

A clarion call for reverence and honor to the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution was made with the “truths” of equality in Thomas Jefferson’s Declaration of being “incontrovertible,” and the guarantees in the Constitution available to “every freeman,” regardless of color, “born in this country all the rights and immunities of citizenship.”[29] As historian Christopher Bonner has recently noted in his important book, Remaking the Republic, when Black “activists called themselves citizens of the United States or appealed to federal authority, they made themselves known part of urgent conversations about what constituted the United States, who belonged in the country, and how its government should relate to individual Americans.”[30]

Support was given for abolitionist papers including editor Benjamin Lundy’s Genius of Universal Emancipation (Ohio), William Lloyd Garrison’s Liberator (Massachusetts), and the newly created, African Sentinel (New York). Prominent white abolitionists, including Garrison and Lundy, along with the wealthy New York merchant and philanthropist Arthur Tappan, addressed the convention. The Liberator, whose readership was made up of predominantly free Blacks in the northern states when it began in January 1831, officially ended its run in 1865 when the Civil War ended. Garrison was recognized as the “bold and uncompromising advocate for the rights of man.”[31]

Building on the work of the previous September, a continued call for emigration to Canada was sounded, as well as a stinging attack on the American Colonizationist Society, which was viewed as nothing more than a naked attempt to “perpetuate slavery,” along with the continued necessity of “education, temperance, and economy” for Blacks. These approaches were considered the best weapons to combat northern racist laws. The threat of colonization was especially strong in Pennsylvania with over eighty local groups promoting the removal of Blacks from the United States to Africa.[32]

A strong claim to birthright citizenship (“birth constitutes citizenship” to quote from one address) was made. It was a triumphant reminder that Blacks had helped to fight for the liberty that white Americans held so dear.[33] Fundraising efforts to build a Black college in New Haven were discussed as well, but the plan ultimately failed due to white resistance at Yale and in the greater community.[34]

In 1832, Providence’s Ichabod Northup journeyed to Philadelphia to serve as a delegate from Rhode Island. Northup’s father fought in the Revolutionary War in the First Rhode Island Regiment.[35] George Willis and Alger Niger continued in their roles as vice president and corresponding secretary. The same was true of Willis and Niger at the 1833 gathering though Northup was not in attendance; instead, George Spywood of Providence took his place.[36] Delegates in 1832 and 1833 met at the Benezet Hall on Seventh Street, an important gathering spot for Black leaders in the city, and in the First African Presbyterian Church. In 1832, delegates met under the cloud of “recent occurrences” in the South, a reference to the white-backlash to a slave uprising in Virginia in August 1831, and a “reign of terror and persecution.”[37] The necessity of establishing a permanent settlement in Canada remained at the forefront of convention business.

At the 1833 convention, white Rhode Islander Arnold Buffum addressed the assembly about a controversy in Connecticut over a new school that welcomed African Americans. The defeat of a recent proposal to start a Black college in New Haven, near Yale University, served as the backdrop for the embroglio over abolitionist and native Rhode Islander Prudence Crandall’s school in nearby Canterbury, Connecticut. Rhode Islanders, father and son, George and Henry Benson, were also actively involved, linking the white backlash over Crandall’s school to the spirit of colonization. “They are genuine flowers of the Colonization garden. Let the real friends of the people of color, who have been deluded by the professions of the Colonization Society, read and ponder,” wrote the young Benson in an editorial.[38] During the ensuing trial, the trial judge specifically called out the Bensons stating that if they were to return to Canterbury they would be fined.[39]

In 1832, Crandall’s previously all-white Canterbury Female Boarding Academy entered the spotlight after admitting a Black student named Sarah Harris. Not one to back down, Crandall decided to run a school for “Young Ladies and Little Misses of Color.”[40] A violent white backlash ended the experiment. The ensuing case of Crandall v. State involved a Connecticut statute banning the private schooling of free Blacks from outside the state (several came from Providence and Massachusetts). Crandall’s attorneys argued that the Connecticut statute violated the Privileges and Immunities Clause of Article IV of the federal Constitution. The judge in the case, in a vein similar to the infamous future ruling by U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger Taney in the Dred Scott case (1857), ruled that African Americans were not citizens.[41]

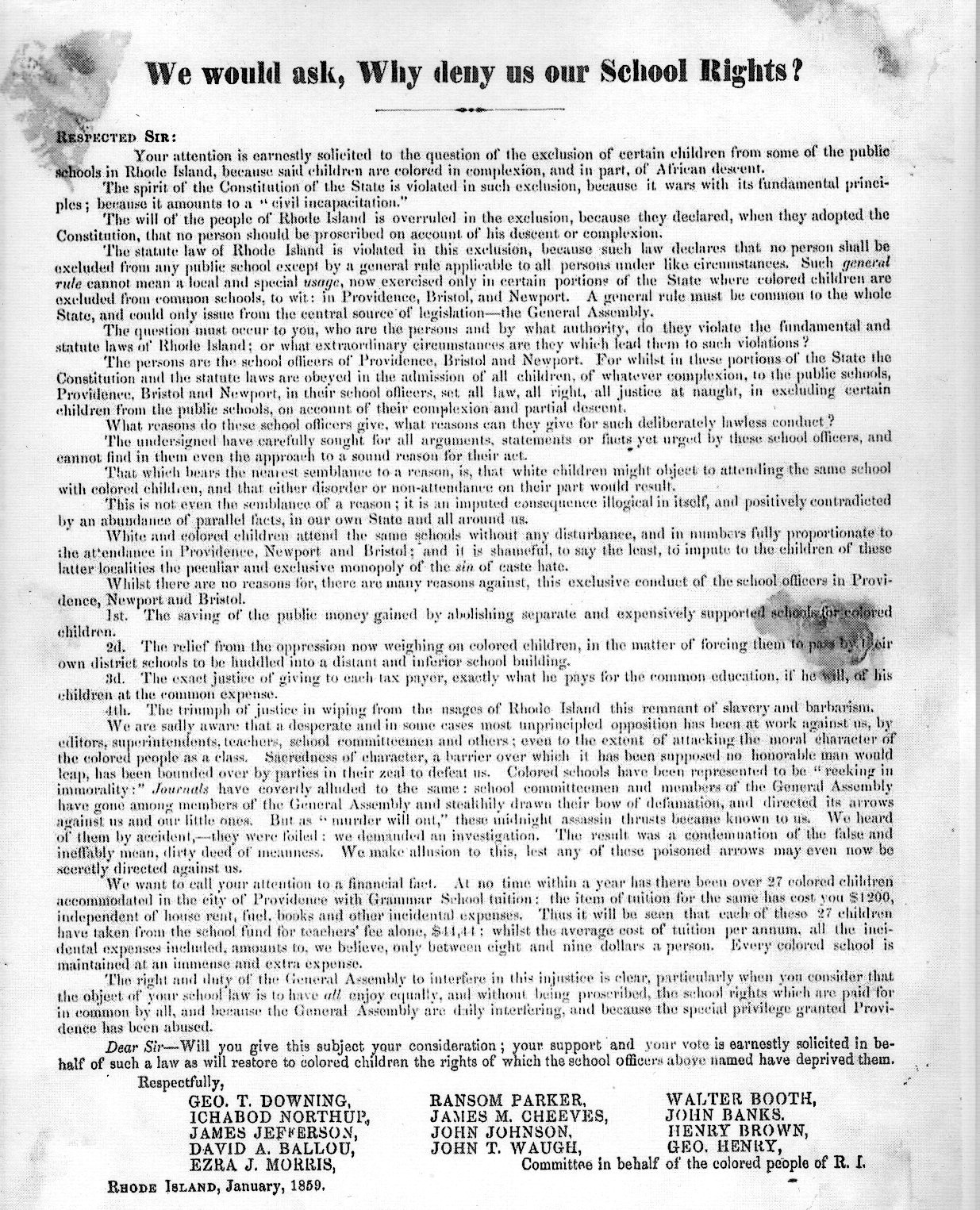

Broadside demanding that Providence schools be desegregated, with first signatories by Black leaders George Downing and Ichabod Northup, 1859 (courtesy of John Hay Library, Brown University Library)

In June 1834, the annual Black convention meeting moved from Philadelphia to New York City. Willis and Niger were again in attendance, maintaining their leadership roles. Fidelity was given to the newly formed American Anti-Slavery Society and continued attacks against the American Colonizationist Society were levied.

In June 1835, the convention movement returned to Philadelphia, this time convening at Wesley A.M.E Zion Church. This would be the final convention of the decade, with eight years elapsing before the return of a large national convention in Buffalo, New York.[42] Alfred Niger and Nathan Gilbert served as Rhode Island delegates, with Niger helping to pen the major address of the convention. George Willis remained a vice-president. William J. Brown of Providence took over for Niger as corresponding secretary.[43]

Arnold Buffum once again traveled to Philadelphia to address the convention. The convention closed with an invocation of the declaration:

that the laws of our country may cease to conflict with the spirit of that sacred instrument, the Declaration of American Independence. We believe in a pure, unmixed republicanism, as a form of government best suited to the condition of man, by its promoting equality, virtue, and happiness to all within its jurisdiction. We love our country, and pray for the perpetuation of its government, that it may yet stand illustrious before the nations of the earth, both for the purity of its precepts, and the mildness and equability of its laws.[44]

As historian Kate Masur argues in her award-winning work, Until Justice Be Done, Black activists pursued better conditions for their communities at both the local and national level and sought to build broader interstate support for the cause of equal rights. African Americans activists “had entered the conversation by taking what everyone understood as the bold step of petitioning” state legislatures and laying claim to the rights of citizenship.[45] The future Rhode Island civil rights leader George Downing learned the importance of petitioning from his father Thomas, a delegate to the early Black conventions in Philadelphia and New York.[46] Later, building on the work of Alfred Niger, George Willis, and Ichabod Northup, George Downing worked towards the establishment of full measures of citizenship protected under federal law.[47]

In 1841, Ichabod Northup, along with a number of other leading Black citizens, petitioned numerous constitutional conventions held in Rhode Island for the right of suffrage. In October 1841, Northup helped to author a petition to the so-called People’s Convention meeting in Providence, questioning why delegates were contemplating excluding Blacks from the franchise in their proposed “People’s Constitution. He wrote,

[We] protest against it as anti-republican. We know of no authoritative standard, where the right of man to participate in the privileges of government is predicated of their personal appearance or bodily peculiarities. We know of no system of political ethics in which rights are based upon the complexion of the skin. We can find no nation that has the temerity to insult the common sense of mankind by promulgating such a sentiment as a part of its political creed.[48]

A month later, Northup helped to co-author another petition, this one sent to a constitutional convention authorized by the General Assembly.[49] In the end, by the fall of 1842, Black leaders had worked hard to negotiate favorable ties with white elites in order to ensure that Rhode Island’s African Americans received the rights due to them as citizens. They understood that equating the rights of citizenship with skin color brings “a stain upon the state.”[50]

Notes:

[1] See the file at the Rhode Island State Archives containing the four-page petition and the response of the General Assembly. Note: Sometimes Willis appears as Wyllis. For more on these three leaders see CJ Martin’s informative essay in the Online Review of Rhode Island History: https://smallstatebighistory.com/the-mustard-seed-providences-alfred-niger-antebellum-black-voting-rights-activist/ [2] Quotes from an anti-colonizationist meeting led by Niger and Willis in November 1831 in the meeting house. See the Liberator, November 5, 1831. The local Liberator agent in Rhode Island was George Benson. [3] For 1831, see https://omeka.coloredconventions.org/items/show/72 and for 1832, see https://omeka.coloredconventions.org/items/show/229. The best discussion of the Providence race riots—the 1824 Hardscrabble Riot and the 1831 Snow Town Riot—can be found in CJ Martin, The Precious Birthright: Black Leaders and the Fight to Vote in Antebellum Rhode Island (University of Massachusetts Press, 2024), 83-118. [4] See the file at the Rhode Island State Archives containing the four-page petition and the response of the Assembly. [5] For an account of Rhode Island’s involvement see the podcast RIHP 11: Baumgartner, Casey, and Muller on RI and the Colored Conventions Project: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/rihp-11-baumgartner-casey-and-muller-on-ri-and/id1588408442?i=1000555960805 [6] See Richard Newman, The Transformation of American Abolitionism: Fighting Slavery in the Early Republic (University of North Carolina Press, 2002), 103-104. [7] See 1835 records at https://omeka.coloredconventions.org/items/show/277 [8] See Deborah Bingham Van Broekhoven, The Devotion of These Women: Rhode Island in the Antislavery Network (University of Massachusetts Press, 2002) and two articles by John Myers “Antislavery Agencies in Rhode Island, 1835 -1835” (1970) and “Antislavery Agents in Rhode Island, 1835 – 1837” (1971) in Rhode Island History, available at https://www.rihs.org/history_journal/rhode-island-history-journal-vol-29-july-oct-1970/ and https://www.rihs.org/history_journal/rhode-island-history-journal-vol-30-january-1971/See also CJ Martin, The Precious Birthright: Black Leaders and the Fight to Vote in Antebellum Rhode Island and the review of this important book authored by Chaput and DeSimone at the Online Review of Rhode Island History https://smallstatebighistory.com/book-review-cj-martin-the-precious-birthright-black-leaders-and-the-fight-to-vote-in-antebellum-rhode-island-university-of-massachusetts-press-2024/

[9] See 1831 records at https://omeka.coloredconventions.org/items/show/72. [10] See Hamilton’s 1834 address at https://omeka.coloredconventions.org/items/show/601 [11] Van Gosse, The First Reconstruction: Black Politics in America from the Revolution to the Civil War (University of North Carolina Press, 2021), 87. [12] See https://coloredconventions.org/first-convention/origins-1830-convention/traditional-origin-story/ and https://coloredconventions.org/first-convention/origins-1830-convention/other-precursors/ [13] See Henry Louis Gates, Jr., and Donald Yacovone, The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross (Smiley Books, 2013), 92-93. [14] See Richard Newman, Freedom’s Prophet: Bishop Richard Allen, the AME Church, and the Black Founding Fathers (New York University Press, 2008). [15] David W. Blight, Yale and Slavery: A History (Yale University Press, 2024), 143. [16] See the informative discussion posted by the editors of the Colored Convention Project website at https://coloredconventions.org/first-convention/is-1830-first-convention/the-attendance/ [17] Douglas R. Egerton, “‘Its Origin Is Not a Little Curious’: A New Look at the American Colonization Society,” Journal of the Early Republic 5:4 (1985), 463–80. [18] See 1834 records at https://omeka.coloredconventions.org/items/show/276. [19] Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and Donald Yaconne, The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross (New York: Smiley Books, 2013), 94. See also Manisha Sinha, The Slave’s Cause (Yale University Press, 2016), 199-205. [20] See the 1832 records on the incredible Colored Convention Project website at https://omeka.coloredconventions.org/items/show/229. [21] See Minutes of the Fifth Annual Convention of the Free People of Color (1835) at https://omeka.coloredconventions.org/items/show/277. See also Howard Bell, “The American Moral Reform Society, 1836-1841,” The Journal of Negro Education 27 (1958), 34–40. [22] Gosse, The First Reconstruction, 90. [23] Martin, Precious Birthright, 120 and Stephen Kantrowitz, More Than Freedom: Fighting or Black Citizenship in a White Republic, 1829-1889 (Penguin Press, 2012), 43-44. [24] Eddie S. Glaude, Exodus: Religion, Race and Nation in Early Nineteenth Century Black America (University of Chicago Press, 2000), 114. [25] 1830 records at https://omeka.coloredconventions.org/items/show/70. [26] Ibid. [27] A detailed statement on the origins of the 1830 meeting and the gathering the following year can be found in the minutes of the 1832 convention at https://omeka.coloredconventions.org/items/show/229.For more on the Colored Convention Project website and for classroom use, see Erik J. Chaput, “Nativity Gives Citizenship”: Teaching Antislavery Constitutionalism through the Black Convention Movement,” Common Place (March 2023), available at https://commonplace.online/article/teaching-antislavery-constitutionalism/.

[28] See obituary in Pacific Appeal, November 8, 1873 (accessed online via the California Digital Newspaper Collection). [29] See 1832 records at https://omeka.coloredconventions.org/items/show/229. [30] Christopher James Bonner, Remaking the Republic: Black Politics and the Creation of American Citizenship (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020), 50. [31] See 1832 records at https://omeka.coloredconventions.org/items/show/229. [32] Newman, Transformation of American Abolitionism, 117. [33] See 1833 records at https://omeka.coloredconventions.org/items/show/275. [34] Kabria Baumgartner, “Gender Politics and the Manual Labor College Initiative at National Colored Conventions in Antebellum America,” in Sarah Lynn Patterson, Jim Casey, and P. Gabrielle Foreman, eds., The Colored Conventions Movement: Black Organizing in the Nineteenth Century (University of North Carolina Press, 2021), 231-232. See also Blight, 145-153. [35] See the research of historians Robert Geake and Fred Zilian at https://rishm.org/patriots-park-the-black-regiment/. [36] Spywood appears in 1830 and 1840 census enumerations for Providence. He was one of the signers of an 1841 petition to the General Assembly dealing with the repeal of an 1841 act exempting real and personal property of African Americans from taxation. Joining Spywood in the appeal was Ransom Parker and Ichabod Northup. For the 1830 and 1840 federal census, see: https://www.census.gov/library/publications/1832/dec/1830b.html & https://www.census.gov/library/publications/1841/dec/1840b.html [37] Henry Mayer, All on Fire: William Lloyd Garrison and the Abolition of Slavery (W.W. Norton, 2008), 120-123. [38] See https://glc.yale.edu/sites/default/files/files/Henry%20B%20Benson.pdf. See also the letter from George Benson to William Lloyd Garrison, August 1833, at https://archive.org/details/lettertomrwlloyd00bens/mode/2up. [39] See the Liberator, January 20, 1833, for an account of the trial judge’s decision. Henry Benson, the son of George Benson, was the Rhode Island agent for the Liberator newspaper. He also served as Recording Secretary for the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society. Benson died shortly thereafter in 1837 at the age of 23 years old. His father died later in the year. [40] Rhode Island civil rights activist George Downing’s future sister-in-law, Theodosia deGrasse, attended the Crandall school. For more on the Crandall affair and Rhode Island young women who attended the school see Christian McBurney’s detailed article in the Online Review of Rhode Island History: “Prudence Crandall, Sarah Harris Fayerweather and Ann Hammond: Their Pre-Civil War Struggle for Equality for Black People” (2020) at https://smallstatebighistory.com/prudence-crandall-sarah-harris-fayerweather-and-ann-hammond-their-pre-civil-war-struggle-for-equality-for-black-people/ [41] See Blight, Yale and Slavery, 154-155, 166-167. [42] See 1843 records at https://omeka.coloredconventions.org/items/show/278. [43] See William Brown, The Life of William J. Brown of Providence, R.I.: With Personal Recollections of Incidents in Rhode Island (Providence, 1883). [44] See 1835 records at https://omeka.coloredconventions.org/items/show/277. See also Martin, Precious Birthright, 134-135. [45] Kate Masur, Until Justice Be Done: America’s First Civil Rights Movement, From the Revolution to Reconstruction (New York: W.W. Norton, 2021), 118. [46] Thomas Downing was a wealthy New York City restaurateur and civil rights leader. In the 1840s, Thomas Downing underwrote an expansion of his business in Newport led by his son George. Later, George Downing took a leading role in the desegregation of Rhode Island schools. See Erik J. Chaput and Russell J. DeSimone’s article in the Online Review of Rhode Island History: “The End of School Desegregation in Rhode Island,” https://smallstatebighistory.com/end-school-desegregation-rhode-island/ [47] Erik J. Chaput and Russell J. DeSimone, “George T. Downing and the “Fraternal Unity of Man”: The Battle for an Abolition Democracy in Nineteenth-Century America,” Newport History (2024), 1-35. The authors are currently at work on a full-length biography of Downing. [48] The memorial is reprinted on pp.111-112 of the 1844 Congressional report on the Dorr Rebellion at https://archive.org/details/rhodeislandinter00unituoft/page/110/mode/2up?q=%22political+creed%22. [49] “Memorial of the Colored Citizens of Rhode Island” (signed Thomas Howland, Ichabod Northup, James Hazard, and James Grimes), Nov. 4, 1841. Constitutional Convention, 1841-42, Box 1, Folder 6, Rhode Island State Archives. [50] Phrase taken from the November 1841 memorial. See also the discussion in Chaput, The People’s Martyr: Thomas Wilson Dorr and His 1842 Rhode Island Rebellion (University Press of Kansas, 2013), 60-75 and Erik J. Chaput and Russell J. DeSimone, “Strange Bedfellows: The Politics of Race in Antebellum Rhode Island.” Common-Place (January 2010) at https://commonplace.online/article/strange-bedfellows/.