The Providence author Catharine Read Williams often liked to refer to the tumultuous political and constitutional storm that swept Rhode Island in 1841-42 as a “tempest in a teapot.” The issues that led to the short-lived rebellion that bore the name of her close friend, Thomas Wilson Dorr, was, in one sense, confined to the tiny state of Rhode Island, but recent scholarship on the Dorr Rebellion and the life of Providence reformer Thomas Wilson Dorr demonstrates that the constitutional crisis in this “teapot” had far reaching national implications and was connected with significant cross-currents of the nation’s political culture in the antebellum period.[1]

In any event, what happens in Rhode Island is still important to Rhode Islanders today. CJ Martin (Visiting Assistant Professor at the College of the Holy Cross) has produced a short, and highly readable and informative, history that broadens the study of the Dorr Rebellion even further through an examination of Black abolitionists and the civil rights movement in the pre-Civil War period. Martin’s work is indeed the most important book on antislavery and abolition in Rhode Island to be published since Deborah Van Broekhoven’s 2002, The Devotion of These Women. His work sheds considerable light on the formation of the Providence Anti-Slavery Society (1833) and the Rhode Island Anti-Slavery Society (1836), two important organizations that often get overlooked in general narratives of the period. Martin’s The Precious Birthright will be required reading for all those interested in questions of the privileges and immunities of citizenship, both state and federal, which began in earnest in the early 1820s with the debate over Missouri’s new constitution and carried all the way to the ratification of the 14th Amendment in the wake of the Civil War’s end.

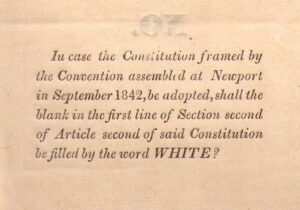

An actual election ticket used to determine if the word “white” should be inserted in the article on suffrage (Russell J. DeSimone Collection)

The Precious Birthright should be read in conjunction with historians Kate Masur’s Until Justice Be Done: America’s First Civil Rights Movement, From the Revolution to Reconstruction (2021) and Manisha Sinha’s The Slave’s Cause (2017). Martin’s The Precious Birthright demonstrates how Rhode Island’s Black leadership class, largely located in Providence by the 1820s, “put together a multifaceted campaign of self-liberation that included a unique combination of agitation and accommodation to republican ideals in order to achieve for themselves the ultimate right of citizenship” – that is, the right to vote.(4) Key figures discussed in the book include, among others, Alfred Niger, George Wyllis, and John W. Lewis, although James Jefferson is missing from the book. (John W. Lewis, a Black Baptist minister who left Providence to spread abolition across northern New England and New York, is reportedly the subject of Martin’s next book.) The quest for racial equality and civil rights was daunting as the minister Hosea Easton, a close associate of the fiery Black abolitionist David Walker, noted in an 1828 sermon in Providence:

Are we eligible for an office? No. – Are we considered subjects of the government? No. –Are we initiated into free schools for mental improvement? No. – Are we patronized as salary men in any public business whatsoever? No. – Are we taken into a social compact with Society at large? No. – Are we patronized in any branch of business which is sufficiently lucrative to raise us to any material state of honor and respectability among men, and thus qualify us to demand respect from the higher order of society? No. – But to the contrary. Everything is withheld from us that is calculated to promote the aggrandizement and popularity of that part of the community who are said to be the descendants of Africa.[2]

The crux of Martin’s story covers the rise of a powerful Black abolitionist movement in the early 19th century that was determined to end racism and slavery, not through colonization schemes that were advanced at the end of the 18th century (a topic Martin discusses at length), but through a fundamental reform of the racist understanding of who was and who was not a citizen of Rhode Island. As Martin makes clear, opposition to emigration and colonization movements became a core principle of the ideology of Rhode Island Black abolitionists as they called for equal rights and the prerogatives of citizenship.

The Precious Birthright opens in the post-Revolutionary period with a discussion of the impact of the passage of the state’s 1784 gradual emancipation act. Martin devotes coverage to a few Black emigration and missionary efforts at the end of the 18th century, the Free African Union Society, with branches in Newport and Providence, along with lives of fascinating figures, such as Newport Gardner, the subject of a forthcoming biography by Providence College history professor Ted Andrews. Through a discussion of Anthony Kinnicutt, a prosperous victualler on Providence’s wharfs, Martin, at page 41 of his book, discusses the weapons Blacks utilized to combat racism: “the rhetoric of liberty, the found philosophy, which included the exploitable contradictions of natural, unalienable rights theory and race ideology.”

The next chapter follows the Black leadership class after the insertion of the word “white” into the state’s voting structure in 1822. Black men who met certain qualifications had the right to vote, but for unclear reasons that was taken away from them. This was a unique development in Rhode Island because unlike other northern states, the denial of Black voting did not coincide with an expansion of the franchise for white males. Indeed, Rhode Island by this period, as historian Patrick T. Conley aptly put it in his classic 1977 work, was a “democracy in decline.”[3] By the 1820s, despite adverse conditions, the Providence Black community had lifted itself up and was able to establish its own churches, schools, and civic organizations. In point of fact some community members prospered and acquired sufficient wealth, with many owning homes, which would have qualified them to vote, even under the state’s stringent property requirement, had not the restrictive enactment of 1822 prevented them from doing so.

Martin is to be commended for his detailed coverage of the African Union Meeting House in Providence. Readers will learn about, among others, George Willis, a sexton in Providence’s First Baptist Church and then deacon in the African Union Meeting House, a minor figure in the national Black Convention movement, a significant player in Providence’s temperance movement, and a major player in the push for Black voting rights in Providence in the early 1840s.

Building on the work of Manisha Sinha, Martin demonstrates that the new wave of abolitionism that gripped the North in the late 1820s was being pushed by African American associational activism. Martin’s detailed analysis of the deadly race riots that gripped the town of Providence in 1824 and 1831, along with the impact on the Black leadership class, constitute the best published work done by a historian on the subject. Martin chronicles the revival of a Black masonic lodge in Providence in the wake of the 1824 riots, along with the formation of the African Society for Mutual Relief and, building on the work of historian J. Stanley Lemons, the creation of Freewill Baptist Congregation in the African Union Meeting House.[4] A keen student of Rhode Island politics in the Jacksonian period, Martin provides coverage of the state-level gag rule debate that raised the specter of racialized debates in the mid-1830s.[5]

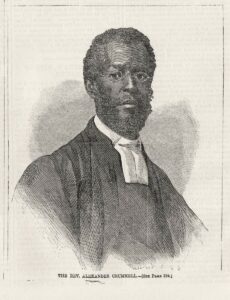

The Precious Birthright ends with two engaging and lengthy chapters on the constitutional crisis that gripped Rhode Island in the spring of 1842. Martin sees the discussion of Black voting moving from the margins to the center of the intense debate to revise the state’s archaic governing structure. The author provides a detailed analysis of the complex interplay between Black leaders, including the Episcopalian minister Reverend Alexander Crummell, and the Rhode Island Suffrage Association. In the summer of 1841, the Suffrage Association called for a constitutional convention to convene on the first Monday in October to frame a new constitution. The August 27th issue of the New Age newspaper, the organ of the Suffrage Association, included: “Let every man who is in favor of a Republican form of government go to the polls on the last Saturday in August, and vote for men good and true, to assemble in the Convention… .” And “TO THE POLLS TO-MORROW: Let every American citizen in the State devote the day to his country ….” Up until this time, Blacks were likely involved in the reform cause, possibly attending Suffrage Association meetings, but despite the inclusive implication of the Association’s election announcements, Black voters were turned away on election day.

The Reverend Alexander Crummell was instrumental in petitioning the People’s Constitutional Convention to support Black suffrage (Russell J. DeSimone Collection)

Though Blacks were prevented from voting for delegates to the People’s Convention, a fierce battle did erupt within the extralegal constitutional enclave about the necessity of bringing African Americans into the body politic. However, in the end, a “white-only” suffrage clause was inserted in the so-called People’s Constitution.[6] An attempt by Black leaders to petition a constitutional convention authorized by the General Assembly bore little fruit as well. Eventually, in the aftermath of the short-lived rebellion in the fall of 1842, Blacks were re-enfranchised after a plebiscite authorized by yet another constitutional convention was taken on the issue. The resolution read:

Resolved, That the question whether native-colored male citizens shall have the right to vote, if possessed of the qualifications required of native white male citizens, be submitted to the qualified voters, on the question of adopting the Constitution, in a separate Article from the Constitution.

This resolution was approved by Rhode Island voters in November 1842, marking the only instance in the antebellum period in which Black voting was restored at the state-level.

Martin views the use of Black troops as being vital to the success of the state authorities against militia units aligned with Providence attorney Thomas Wilson Dorr. In all, about 200 Black men took part in support of the Charter government during the Dorr Rebellion. This support included policing the streets of the city, manning fire companies, joining the militia companies for deployment to Woonsocket, Pawtucket and Chepachet, and, ultimately, guarding Dorrite prisoners, many of whom would suffer in prison cells for months.

While Martin deserves considerable credit for broadening out the conversation about citizenship and voting rights in Rhode Island by linking it to the issues raised by Black abolitionists in the state before the Dorr Rebellion, he goes a bit too far with assertions that the issue of Black voting served as the proverbial hill that the Dorrite cause died on. Moreover, Martin neglects to discuss the impact of Dorr’s failed attempt to solicit support in the corridors of power in Washington, D.C., along with the show of support provided by President John Tyler for the sitting state government at the time under Governor Samuel Ward King. Ironically, Dorr’s political ideology, despite the association with a racist “white-only” clause in the People’s Constitution, sent shivers down the spine of white southerners, leading to a profound backlash from southern Democrats in Congress.[7] Also, it is important to note that Dorr was stationed at the village of Chepachet in northern Rhode Island to reconstitute the People’s Government and not to wage war. The members of the People’s militia were at Chepachet to act as protection for Dorr as he was wanted by the Charter government and there was a $5,000 reward for his capture. The People’s militia was a small group and ill trained or prepared to fend off the 3,500 member Charter militia. Even if the state government deployed a smaller military force (with or without Black troops included) these units would have easily overtaken the Dorrite forces in the village. As it was, most of the Dorrites ran off (including Dorr) without firing a shot. That being said, white supporters of the conservative state government forces appreciated the willingness of Black men to take up arms. Dorr’s forces were also severely depleted due to the impact of martial law and an injunction placed by the Bishop of Boston preventing Irish Catholics in Providence and surrounding mill villages from taking part. Indeed, the overall impactful nativist tactics used by Governor King’s government to scare off support for Dorr’s cause proved to be highly effective. In Rhode Island, Irish Catholics, a sizable immigrant block, were deemed to be outside the body politic in much the same way as African Americans were at the time.

These points aside, CJ Martin has written an important book deserving of a wide readership. The Precious Birthright belongs on the shelves of all students of the state’s history. His foray into the Black Convention movement should also spark future historians to trace the impact of Rhode Islanders in this little known and often underappreciated aspect of abolitionism in the pre-Civil War years. And his discussion of the interplay of Black voters with the Whig Party after the Dorr Rebellion should spark further research and discussion.[8]

Notes:

[1] See Erik J. Chaput, The People’s Martyr: Thomas Wilson Dorr and His 1842 Rhode Island Rebellion (University Press of Kansas, 2013); Patrick T. Conley, Democracy in Decline: Rhode Island’s Constitutional Development, 1776-1841 (Rhode Island Historical Society Press, 1977; reprinted by the Rhode Island Publications Society, 2019) and the Dorr Rebellion Project website hosted by Providence College at https://library.providence.edu/dorr [2] George R. Price and James Brewer Stewart, eds., To Heal the Scourge of Prejudice: The Life and Writings of Hosea Easton (University of Massachusetts Press, 1999), 54. See also Richard Archer, Jim Crow North: The Struggle for Equal Rights in Antebellum New England (Oxford University Press, 2017). [3] Patrick T. Conley, Democracy in Decline: Rhode Island’s Constitutional Development, 1776-1841 (Rhode Island Historical Society Press, 1977; reprinted (with a new preface authored by Erik Chaput) by the Rhode Island Publications Society, 2019). [4] One notable omission in Martin’s bibliography is J. Stanley Lemon’s comprehensive work, Retracing Baptists in Rhode Island: Identity, Formation, and History (Baylor University Press, 2019). [5] For more on the Gag Rule debate in Rhode Island see Chaput and DeSimone, “Third Century of Liberty”?: Thomas Wilson Dorr and Debate over the Gag Rule in Rhode Island, 1835-1836,” on this website, The Online Review of Rhode Island History, at https://smallstatebighistory.com/third-century-of-liberty-thomas-wilson-dorr-and-debate-over-the-gag-rule-in-rhode-island-1835-1836/ and this new page on the Dorr Rebellion Project website devoted to the gag rule debate at https://library.providence.edu/dorr/articles/gag-rule/ [6] See Erik J. Chaput and Russell J. DeSimone, “Strange Bedfellows: The Politics of Race in Antebellum Rhode Island,” Common-Place: The Journal of Early American Life (2010) at https://commonplace.online/article/strange-bedfellows/; See also Caleb T. Horton, “The Tide Taken at the Flood”: Black Suffrage Movement During the Dorr Rebellion” at https://www.providenceri.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Tide-Taken-at-the-Flood.pdf; Irving H. Bartlett, From Slave to Citizen (Providence, 1954). Bartlett gives a detailed account of the development of the Providence Black community and its attainment of social self-sufficiency. [7] See Erik J. Chaput, “Proslavery and Antislavery Politics in Rhode Island’s 1842 Dorr Rebellion,” The New England Quarterly (Winter, 2012), 658–694. [8] See the digital records on the Colored Convention project website at https://coloredconventions.org/about-records/