Rhode Island’s fortifications were in a state of disrepair by the end of the Revolutionary War. The Rhode Island Assembly ordered, in October 1784, that the works on Goat Island be repaired and armed. The renovated fort was renamed Fort Washington. A decade later, in early 1794, the United States Congress, concerned by the outbreak of war in Europe in 1793, decided to create a unit of artillerymen and engineers. It appointed a committee to study the coastal defenses and appropriated money to construct a number of fortifications.

Newport was one of twenty-one locations selected to be fortified. As the new country lacked trained engineers to supervise the construction, Secretary of War Henry Knox contracted a number of European engineers for the task. Major Etienne Nicholas Marie Bechat, Sieur de Rochefontaine, whose name was anglicized to Stephen Rochefontaine, was appointed the engineer for New England on March 29, 1794. He would draw three gorgeous maps that are the subject of this article. Each one is currently held by the Rhode Island State Archives.

Stephen Rochefontaine was born near Reims, France, in 1755 and came to America in 1778 after failing to gain a position in the French Royal Corps of Engineers. He volunteered in General Washington’s Army on May 15, 1778 and was appointed captain in the Corps of Engineers on September 18, 1778. Congress granted Rochefontaine the brevet rank of major on November 16, 1781 for his distinguished services at the siege of Yorktown. He returned to France in 1783 and served as an infantry officer, reaching the rank of colonel in the French Army. He came back to the United States in 1792. President Washington appointed him a civilian engineer to fortify the New England coast in 1794. After the new Corps of Artillerists and Engineers was organized, Washington made Rochefontaine a lieutenant colonel and commandant of the new Corps on February 26, 1795. Rochefontaine started a military school at West Point in 1795, but the building and all his equipment were burned the following year. He left the army on May 7, 1798, and lived in New York City, where he died on January 30, 1814. He is buried in old St. Paul’s Cemetery in New York.[1]

Upon his appointment as the engineer to fortify the New England coast, Stephen Rochefontaine immediately began to design three fortifications for Narragansett Bay: a work on Goat Island to replace Fort Washington, another on Tonomy Hill, which he called Tomany Hill (now called Miantanomi Hill), and a battery at Howland’s Ferry. He also proposed restoration of the fort at Butts Hill. The plans, all dated July 10, 1794, are discussed below.

Lieutenant Colonel Stephen Rochefontaine was in Boston on August 16, 1796 when he wrote to Rhode Island Governor Arthur Fenner requesting additional funds to complete the fortifications. He also sent copies of the plans and buildings for both the defenses under construction and for those he proposed to erect.[2]

Rochefontaine noted that the sums granted “were so small, that I could not complete the plan of fortification calculated to put that Island beyond any danger of being conquered by a foreign Enemy.” He expected that the additional funds “will sufficiently remove all fear of being insulted, or put under contribution by a small force such as 2 or 3 ships of the line, and 10 or 12 hundred men of Land forces.” He proposed “to restrain our fortifications to the number of defenders easily to be collected together in case of an attack, than to be at a very great expense of erecting fortifications, which we are uncertain to man properly in case of necessity….”

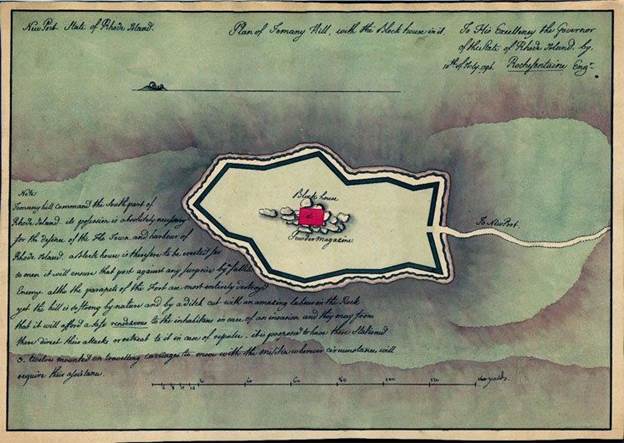

The plan for Tomany Hill noted that the hill commanded the south part of Rhode Island (Aquidneck Island) and that its possession “is absolutely necessary for the defense of the town and harbor.” Rochefontaine noted that the parapets of the fort and moat were entirely destroyed. He proposed to build a block house for fifty men to guard the port against a surprise attack. He also planned to station three artillery pieces (12-pounders) on traveling carriages. Thus, they would be able to move with the militia whenever circumstances would require their assistance. (The previous fortification on the site was garrisoned by the Hessians during the British occupation and at the time of the battle of Rhode Island.)

Fig. 1. Plan for the Fortification at Tomany Hill [Miantanomi Hill] with Block House and Powder Magazine (Rhode Island State Archives)

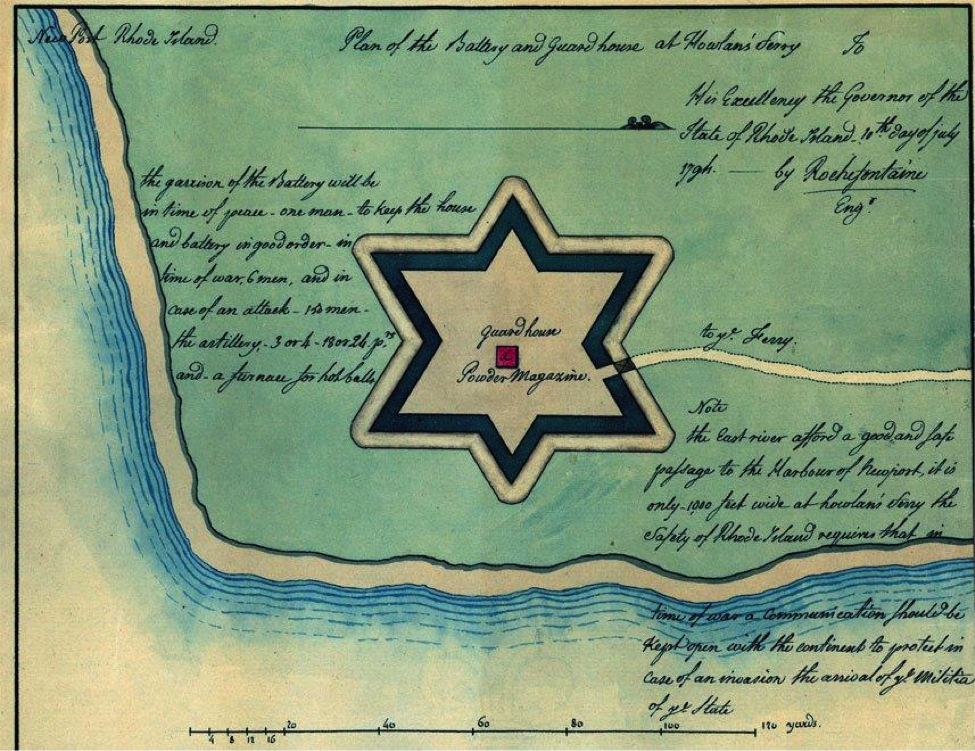

Rochefontaine noted that the East (Sakonnet) River “affords a good and safe passage to the harbor of Newport. It is only 1,000 feet wide at Howland’s ferry and the safety of Rhode Island requires that in time of war a communication be kept open with the continent to protect in case of an invasion the arrival of the militia of the state.”

He planned to erect a battery and a guard house at Howland’s Ferry at the north end of Aquidneck Island. He proposed to garrison the battery with one man in time of peace, to keep it in good order, and with six men in time of war. In the event of an attack, it would accommodate 150 men. The battery would consist of three or four 18- or 24-pounders and a furnace to heat cannon balls.

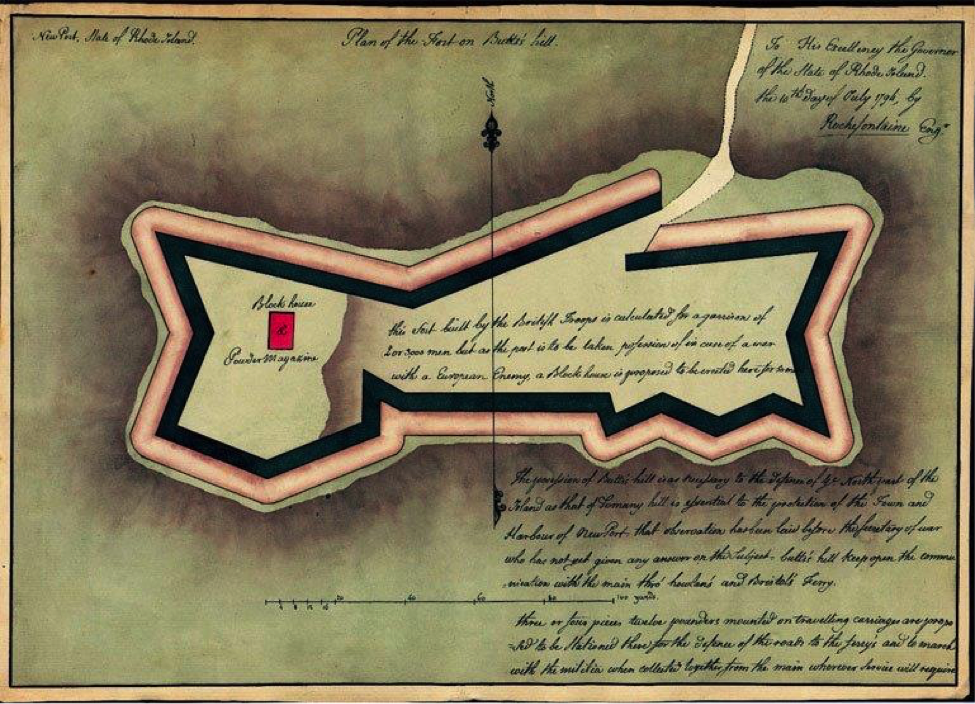

British troops had built fortifications and buildings at Butts Hill (which they called Windmill Hill) after seizing Aquidneck Island in December of 1776 during the Revolutionary War. They continued to occupy the fort at Butts Hill until it became apparent in early August of 1778 that a large New England force was about to invade northern Aquidneck Island. When they withdrew to Newport, General John Sullivan and his troops crossed over from Tiverton and took possession of it. During the ensuing Battle of Rhode Island, the fort was the center of the American defense and where Sullivan made his headquarters.[3]

Rochefontaine stated that Butts Hill was as necessary to the defense of the northern part of Aquidneck Island as Tomany Hill was essential to the protection of the town and harbor of Newport. According to the Frenchman, it would keep open the communication with the mainland and defend the roads to Howland’s and Bristol’s ferries.

Rochefontaine planned to garrison the fort with 2,000 or 3,000 men and proposed to erect a block house on the site, as he expected that the post would be taken possession of in case of war with a European enemy. He also proposed to mount three or four 12-pounders on traveling carriages to be stationed there which would travel with the militia from the mainland when they mustered and moved wherever service would require. Although he had submitted this proposal to the federal government’s new Secretary of War, Henry Knox, Rochefontaine had not yet received any answer before July 10, 1794.

Ultimately, President Thomas Jefferson began a fortification program in 1807 and 1808 that substituted for Rochefontaine’s defensive scheme at what would become a major fort, Fort Adams. This time, American engineers, many of them recent graduates of the new United States Military Academy at West Point, supervised the construction.

[Banner Image: Plan for the Battery and Guard House at Howland’s Ferry (Rhode Island State Archives)]Notes

- “Lieutenant Colonel Stephen Rochefontaine.” In United States Army Corps of Engineers. The geneses of the United States Army Corps of Engineers: a sketch of events from 1775 to 1978 and portraits and profiles of 46 Chiefs of Engineers (Washington, D.C.: The Corps, 1978).

- Rochefontaine, Stephen. “Rochefontaine letter to Governor Fenner,” August 16, 1796. Rhode Island State Archives. Also in Virtual Exhibits, Item #76, http://sos.ri.gov/virtualarchives/items/show/76 (accessed March 27, 2016).

- McBurney, Christian M. The Rhode Island Campaign: The First French and American Operation of the Revolutionary War (Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2011).