Point Judith is a small point of land located about midway between the eastern and western borders of the state. To the east and north of the point the waters from Narragansett Bay enter Rhode Island Sound. To the west and south are the waters of Block Island Sound. For mariners navigating their way to or from Narragansett Bay the significance of this area is well known—and feared. Wind and waves at the location move in different directions, often causing what sailors refer to as “a confused sea.” This condition that can be difficult for all but the largest vessels and particularly for those powered only by the wind. Storms and the all too prevalent New England fog have added to the threatening nature of the seas. These last two elements alone are principally responsible for roughly half of the vessels lost at Point Judith.

The peninsula, sometimes referred to as a small cape, is a little more than a mile in length with a lighthouse at the tip. The first lighthouse on Point Judith was erected in 1810, but it is said that there was a day beacon at that location prior to the Revolutionary War. The original lighthouse was of wood and presented no match for the intense Great Gale of 1815, which destroyed the beacon. Rebuilt within a year, the second lighthouse survived until it was replaced with the current structure in 1857.

The waters around Point Judith have been responsible for shipwrecks throughout the history of Rhode Island. This article will only list those vessels totally lost and in close vicinity to the point. Due to the remoteness of Rhode Island’s south shore particularly in the earliest years, details of some of these losses are scant. It was not unusual for a passing vessel to report sighting a distressed vessel on the rocks and, if there were no survivors to tell the tale, these often were never recorded for posterity.

The following is a listing of 46 vessels that are known to have come to grief at Point Judith. There are undoubtedly more that went to pieces or sunk without a trace and are whose stories are lost. Further information on those listed below is available at the Museum at Beavertail Lighthouse in Jamestown, where a complete database of the marine disasters in Rhode Island waters is available and accessible to the general public.

Along with the 46 vessels wrecked at Point Judith, 14 lives were lost in wrecks occurring after the Civil War. The vessels involved, dates, and lives lost are: PALLADIIUM (April 29, 1881), 2; JOHN G. FELL (Nov. 24, 1901), 1; MOONBEAM (May 3, 1905), 6; LUGANO (Nov. 15, 1906), 3; BRADDOCK (April 28, 1923), 1; and HARVEST (March 24, 1963), 1.

Another important story indicated by these shipwrecks was the courageous work of the surfmen at the Point Judith Life Guard Station to rescue stranded sailors, often in fierce gales.

April 7, 1728. An unidentified sailing vessel en route from Boston to Rhode Island wrecked on the rocks near Point Judith. The New England Weekly Journal of April 15, 1728, tells the story of the loss of the crew: the vessel “ran upon the breakers near Point Judith…the mate who was an active man carried the master and men (which were six or seven)…to the shore, but their being so long in the water, and undergoing other hardships, proved too hard for them, and they all died soon after they got out of the water, though some walked near half a mile and some farther before they expired . . . .

October 14, 1730. An unidentified sailing vessel on a voyage from Connecticut to Boston was caught in a stormy wind and drove ashore at Point Judith, where its master lost his vessel but managed to save his cargo. Specifics on the vessel itself are not known.

October, 1733. An unidentified sloop of about 60 tons, with Jeremy Finn of Bristol its master and owner, ran ashore on Point Judith and went to pieces. The crew survived to tell the tale.

November 6, 1777. During a gale on this morning during the American Revolutionary War, the British frigate SYREN sailing in company with ship SISTERS and the tender TWO MATES, was driven ashore in a storm near Point Judith (although part of the problem lay with the British master of the SYREN who turned to the west too soon before clearing the point). Word of the stranding reached South Kingstown and the local militiamen wasted little time heading to the site as the opportunity of capturing the stranded vessel was too good to pass up. The Patriot forces were successful and those aboard the British ship were taken prisoner and sent to Providence. British navy officers in Newport were informed of the plight of the ship and sent warships to the scene with intention of regaining the ship or destroying her. Ultimately charges were set aboard the vessel and she was destroyed where she lay. However, enterprising Americans had removed from the stranded vessel before it was destroyed the crew, taking them prisoner, several cannon, anchors, some of the sails and rigging, and some ship stores. Nearly forty years later, in 1815, an enterprising diver named Bailey Brooks visited this site and others in the vicinity. From the wreck of the SYREN he retrieved, among other things, an anchor weighing 3,000 pounds. (To read an entire article on this stranding and capture by Christian McBurney, go to Archives on this website and type in the search box: syren.)

March 28, 1778. In an attempt to get to sea to join other American forces, the frigate COLUMBUS departed from Providence headed for the Delaware. Although she ran a gauntlet and avoided cannon fire from enemy vessels in the Narragansett (West) Passage, she was no match for the frigates lying in wait for her outside the mouth of the bay and was forced to run ashore at Point Judith. Good fortune favored her with diminishing winds, thereby preventing British ships from capturing her immediately. This allowed Patriot forces time to abandon and set fire to the COLUMBUS. They also managed to save her stores and some of her cannon but, most importantly, did not allow their vessel to fall into enemy hands.

September 14, 1805. The merchant sloop ELIZA, with a cargo of salt being shipped from Nantucket to Guilford, Connecticut, was cast away on Point Judith. The reason for the stranding was not stated; the vessel and cargo were a total loss.

December 27, 1809. The 245-ton merchant ship INDIA POINT, on a voyage from New Bedford to New York City, had the bad luck of running ashore near the new lighthouse on Point Judith, just one day before it was to be lighted for the first time. Sometimes the loss of a vessel is attributable to the master’s need to rush to deliver a cargo on time, but since Captain Hathaway’s ship was “in ballast” (without cargo) at the time of her loss, it would seem that another single day’s delay in sailing would not have made much of a difference. The 86-foot long ship was six years old when lost near the lighthouse at Point Judith.

November 17, 1811. The 35-ton merchant sloop CAROLINE, Captain Thomas Hastings, en route from Hartford to Providence, was caught in a storm and cast ashore on Point Judith. She was reported lost with most of her unidentified cargo.

February 10, 1819. Trade between Rhode Island merchants and Caribbean islanders was significant business at this time (indeed, since colonial times). Principally, sugar and molasses, ingredients for brewing rum, were the northbound cargos. The brig MARY, with 270 hogsheads of molasses, was lost in fog while attempting to enter Narragansett Bay. It turned to the west a bit too soon, landing on rocks near the lighthouse on Point Judith. Within a week lighters were sent to remove her cargo and almost all were safely landed before she met her fate on the exposed shore.

November 6, 1823. One of the greatest fears known to mariners is fire aboard their vessel. This is particularly of concern in those seasons of the year when water temperatures are cold and the option of burning on board the ship or freezing in the water is a decision a mariner would rather not make. The 99-ton merchant sloop EXPRESS was southbound for Charleston, South Carolina, with a cargo of lime, when she found herself in trouble. As long as it is kept dry, lime is not a dangerous cargo but when wet it is highly combustible. The lime got wet and a fire broke out. The sloop’s master, Captain Samuel Humphreys, did his best to contain the fire, but he eventually resorted to running his vessel ashore near Point Judith, thereby enabling the crew and passengers to save themselves. Once ashore, the cargo fire continued unabated until it consumed the ship as well.

April 24, 1827. The schooner NEW HOPE was en route to Newport with a most dangerous cargo when she ran into a storm. Her cargo was cut stone for the construction of the expanded fortifications at Fort Adams. In heavy seas, if allowed to move freely in the cargo hold, stone can puncture the hull, and allow water in, often with fatal results. Before this fate could befall this schooner, her master ran the vessel ashore on the rocks at Point Judith where she went to pieces.

August 4, 1844. The sloop CHAMPION, of Falmouth, Massachusetts, with a cargo of salt bound for New York City, found herself fogbound when outbound from Providence. She ran ashore on the east side of Point Judith close to the light house. The rocky shore quickly tore holes in her bottom and the seawater started to dissolve the cargo. As she became lighter the vessel beat on the rocks until her bottom was entirely gone and she became a total loss. Only her sails and some rigging were saved; the crew survived too.

October 3, 1853. The schooner VIRGINIA was northbound from Alexandria, Virginia, for Fall River, when she ran ashore on the southwest part of Point Judith at 3 a.m. The nature of her cargo, if any, was not stated, but she was reported as bilged (a hole broken in the bilge area of a ship’s hull), which would have resulted in a total loss of the vessel and any cargo.

July 15, 1857. En route from Port Ewen, New York, on the Hudson River, to Fall River, Massachusetts, with a cargo of coal, the schooner CHARLES PITMAN became another in a long list of victims to New England fog when she became wrecked on Point Judith. First reports indicated that the vessel might be saved but as things worked out she left her bones on among many others at this location.

February 2, 1861. The 430-ton schooner NORTH STATE was traveling northbound from Savannah, Georgia, with 1,000 bales of cotton and bound to Providence, when she ran into a dense fog off Point Judith and ran ashore about one mile to the westward of the point. Salvagers were optimistic, at first, despite that the vessel having bilged. They set at work unloading her cargo and saved 400 bales before the rough seas and wind prevented further work. Although a steam tug had arrived from New York, where she was owned, she would not sail again.

August 4, 1862. Like the NEW HOPE lost thirty-five years earlier, the schooner VICTOR, bound from Quincy, Massachusetts, for Sandy Hook, New York, was carrying a cargo of granite stone when she ran on the east side of Point Judith and became a total loss. The vessel, without cargo, registered 167-tons and was built in Boston in 1838. As was often the case, the cargo was likely a greater loss than the vessel carrying it. Her master, Captain Sears, was also the owner of the vessel, not uncommon with smaller or older vessels during this period.

September 25, 1865. The 47-ton, 55-foot long sloop GEN. KOSSUTH, from Eaton’s Neck, Long Island, bound for Providence with 80 tons of moulding sand, foundered and sank about one-quarter mile south of Point Judith. Captain Edward C. Coe was also the vessel’s owner. The crew managed to escape in the ship’s boat in heavy seas and made it safely to shore. Within a week after the sinking, the newspapers reported her as abandoned where she lay.

December 24, 1866. En route from New York City to Portland, Maine, in ballast, the 257-ton bark C.B. HAMILTON, with a complement of nine men aboard, ran ashore about one mile west of the lighthouse at Point Judith. The wind was blowing “a good stiff breeze” from the west, and although cloudy and hazy weather was encountered, her stranding came as somewhat of a surprise. The vessel was must closer to the shore than its crew anticipated. The wind being at her back, the vessel continued to move forward despite having struck on rocks, but within about one hundred yards of the shore she swung around and became completely unmanageable. The sole small boat aboard was dashed to pieces when launched. Through prompt assistance from the shore the crew was rescued. The strength of the sea and the solid rocks overcame the bark’s copper sheathed hull, which soon was “holed”, causing her ballast (heavy material carried to provide the desired draft and stability) to spill out. The HAMILTON would sail no more.

December 10, 1872. The 298-ton schooner WILLIAM H. TIERS, with a 400-ton cargo of coal, was northbound from Baltimore, Maryland, headed to Fall River, when she ran into a storm described as severe. Captain Hoffman was anxious to make port and probably “cut the corner” at Point Judith a bit too tightly. His nine-year old vessel struck a rock at Point Judith and immediately broached and went ashore, sinking in less than one hour. The sails, rigging, anchor chains and some other materials were saved from the wreck but the vessel went to pieces.

June 12, 1875. A fairly small three-masted schooner of just 145 tons, VICTORIA, of Mystic Connecticut, was carrying 350 tons of coal when she ran aground on Point Judith in the fog. She had sailed from Hoboken, New Jersey, bound for Providence, under the command of Captain G.W. Morgan at the time of the disaster. Just two days after the stranding, she was reported as full of water with her decks washed off.

April 29, 1881. The 89-ton schooner PALLADIUM, of Harwich, Massachusetts, was carrying a cargo of scrap iron from New York City to Providence when she developed a leak during a storm in Block Island Sound. The crew of three men all manned the pumps and were holding their own for about an hour before the schooner suddenly took a plunge to the bottom, about one mile southwest from the Point Judith Life Saving Station. So quickly did the sinking occur that the ship’s boat could not be launched. The captain’s son and the mate of the vessel drowned and the captain only saved himself by climbing into that portion of the rigging that remained above water when the schooner sunk.

August 5, 1881. Another coal schooner was the TILLIE E. and, like the PALLADIUM, she was about average size (93 tons). TILLIE E. had been in service for thirty years. At the time of her loss she was en route from Weehawken, New Jersey, headed to Provincetown, Massachusetts, her home port. The official report of the U.S. Life Saving Service records that the schooner had sprung a leak when about five miles south of Point Judith. In order to save the lives of the crew, her master, Captain Gross, intentionally ran her ashore about one-half mile west of the Point Judith Life Saving Station. As the life saving station at this time was closed during the summer months, the vessel was not spotted in its perilous position for about three hours. But it was seen by one of the regular surfmen passing by, and the master and crew were brought to shore in short order. The vessel was lost, although part of the cargo was saved.

May 10, 1884. The JULIA A. TATE was a small coasting schooner of 96 gross tons and measuring 78 feet in length. The TATE was sailing under the command of her owner, Captain J.M. Tate, and headed for Boston from Brooklyn with a cargo of car axles, pig iron and logwood. Despite her age, with nearly 44 years at sea, the schooner was considered quite staunch; it had been rebuilt in 1869. She ran aground in fog and sank (undoubtedly after striking boulders on the bottom). The weather was smooth at the time and crew members launched their boat and landed on the beach unassisted. Although most of her cargo was recovered by wreckers, the vessel itself ended her days at this location.

December 1, 1886. On a voyage from Perth Amboy, New Jersey, to Somerset, Massachusetts, with a load of pig iron, the 96-ton schooner MARY NATT was off Watch Hill when she discovered that she was leaking. Continuing on toward Narragansett Bay the leak worsened until off Point Judith. Captain Harrington determined that he and his crew were not going to survive this trip if he did not take immediate action. He intentionally ran his vessel ashore about one-quarter mile north of the Point Judith Life Saving Station. All hands were saved by the life savers, but the vessel became a total loss.

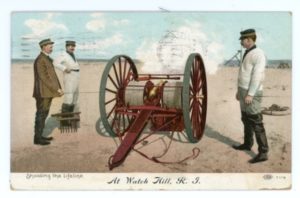

Lifesavers return with their lifeboat to the Watch Hill Life Guard Station (Sanford Neuschatz Collection)

February 20, 1887. Not long after the loss of the MARY NATT, another schooner found herself in trouble off Point Judith. This time it was the three-master HARRY A. BARRY, a 469-ton schooner carrying 450 tons of coal from Baltimore to Fall River. She was making way in a heavy sea when she struck the rocks just offshore from the Point Judith Life Saving Station. The life savers responded immediately and observed crew members attempting to load their boat and come ashore. One man, the cook, was washed overboard but made it to shore on a drifting plank. The remaining crewmen were rescued by the life savers, but the vessel was doomed. Some salvage was performed but the vessel went to pieces in a week.

December 31, 1887. Another three-masted schooner, the MARY A. DRURY, met with a similar accident as she was headed northbound from Norfolk, Virginia, to Providence, with 650 tons of coal on board. In this instance, weather was not the cause. Simple pilot error brought Captain Nickerson and his crew ashore on the point. Two hours later she was floated, but because a leak had developed, she was beached just north of the Point Judith Life Saving Station. Although it was believed that she would be pulled off and return to service, the weather over the next few days turned foul and within a week the schooner went to pieces on the shore.

February 10, 1893. The 97-ton schooner EAST WIND was southbound from Rockport, Maine, headed to Providence, with a cargo of lime. The weather during the voyage had been boisterous and Captain Coombs missed turning into Narragansett Bay and ran ashore on the east side of Point Judith, near the life saving station. All hands were rescued, but the 79-foot long, forty-year-old vessel was doomed.

September 9, 1896. A northeast gale struck the Rhode Island coast with reported wind speeds of up to 72 miles per hour as the tiny 16-ton schooner PAWTUCKAWAY approached Point Judith. She was not alone in being in distress on that stormy day but, unlike most other vessels, she was overwhelmed by wind and sea conditions. She ran ashore and almost immediately went to pieces on Point Judith. Fortunately, her crew had been taken off the vessel shortly before the stranding.

May 12, 1898. The schooner MARY MILLER was another old-timer lost at Point Judith. Built in Philadelphia in 1846, she was over forty years old when lost on a voyage from Port Jefferson, New York, to Newport, carrying a cargo of coal. She developed a leak and her master, Captain Daniel Crowley, decided to anchor her inside the breakwater at Point Judith and pump her out. A tug was called but even the extra pumping capability could not slow the leak. Captain Crowley decided to run her ashore just a little over a mile west of the Point Judith Life Saving Station. All hands were safely removed from the vessel but she would end her days there, partially salvaged but probably not worth the expense to pull her off the beach.

November 24, 1901. Captain Lewis R. Mackey, master of the schooner JOHN G. FELL, lost his life in an attempt to land his yawl boat in heavy surf. The schooner had departed from Tiverton, headed for Jersey City, New Jersey, with 100 tons of scrap iron on board. Soon after departure the thirty-year-old vessel sprung a leak and, as it passed Beavertail Point, it ran into a severe gale. The captain refused to turn back. Approaching the breakwater at Point Judith he brought the 165-ton schooner to anchor inside as his crew continued to try to keep up with the leak. A few hours later the crew, realizing its work was hopeless, abandoned the sinking vessel and made an attempt to land it on the beach. The yawl boat capsized in the heavy surf, killing Captain Mackey. No further mention of the vessel was made so her loss is presumed.

May 3, 1905. The schooner-barge MOONBEAM, Captain Charles P. Ackers, had the misfortune to be caught in a deadly storm. All hands were lost—Ackers, his young son and daughter, and three crew members. At the time of the vessel’s sinking, she was being towed to Providence, with a cargo of coal, from Hoboken, New Jersey. The barge measured 140 feet in length and registered 675 tons. Before she sank, she flashed a signal to her tug, the GERTRUDE, and then blew her steam whistle. But before the tug could reach her she went down. On the day after the sinking, the vessel was seen with her bow headed toward the shore about 900 yards south of the lighthouse. Three weeks after the sinking, divers were sent to the wreck site to destroy the remains with dynamite.

November 15, 1906. Heading southbound for New York City, the schooner LUGANO sailed from Gardiner, Maine, with a cargo of wooden laths. The 174-ton vessel was just under forty years old when lost in a violent east northeasterly storm. Surfmen from the Point Judith Life Saving Station responded to the need of the stricken vessel, attempting to set up a breeches buoy to bring the men ashore. But the intensity of the storm caused that plan to fail and that apparatus was lost. Captain Edmund Barter of the LUGANO realized that if something drastic was not done immediately all the crew would be lost. He grabbed a plank and headed over the side advising the other crewmen to do the same. Four men entered the water and one stayed on the wreck. Two of the swimmers drowned on the trip to the shore, as did the crewman who stayed aboard. The LUGANO became stranded just one-quarter mile from the Point Judith Light House.

December 30, 1907. The 382-ton coal barge JENNIE was northbound from South Amboy, New Jersey, headed for Fall River in a storm. There were at least two barges in the tow on that fateful morning. Word that the JENNIE was in trouble came when the master of the barge IDA, another barge in the string, arrived on the shore in a dory reporting the sinking of his vessel and advising that the JENNIE was anchored about two miles offshore with a leak that would soon take her too to the bottom. The life savers manned the surfboat and rowed to JENNIE’s aid, rescuing those aboard. A few hours later the JENNIE struck the rocks 150 yards east southeast from the Point Judith Life Saving Station and became a complete wreck.

November 24, 1912. The 376-ton barge PIONEER departed from Newport, headed for Jersey City without cargo. John Johnson was in command of the barge when it was anchored along with another barge, TORNADO, inside the breakwater at Point Judith awaiting a break in the weather. A sudden shift in the wind direction proved fatal to the forty-year-old vessel, throwing her on the shore just three-quarters of a mile west northwest from the Point Judith Life Saving Station. At dawn, the PIONEER went to pieces.

December 7, 1914. Barges and coastal merchant vessels were not the only victims of bad weather at Point Judith. The 48-foot long fishing schooner LUELLA NICKERSON, just 26 tons, was anchored inside the breakwater for protection from a northeast gale. Just after daylight, the schooner made her way to the breakwater wall. The wall was suitable for a breeches buoy rescue, so the life savers launched the surfboat and rowed out to rescue the sailors. Amid floating wreckage from the schooner and fighting winds blowing at near hurricane force, the rescuers were able to bring the men safely into the surfboat by means of a line tied to a heaving stick. The danger did not end once the crew were in the surfboat, because the surfboat could not be pulled to shore against the fierce wind. The surfboat remained at anchor inside the breakwater for five hours, waiting out the storm, until the Navy torpedo boat MORRIS happened by. The surfboat was quickly lashed to the steamer and brought to safety, along with the shipwrecked fishermen and the brave surfmen.

A wrecked steam ship after a hurricane, unidentified ship and date (Providence Public Library Digital Collections)

May 1, 1921. Another fishing vessel, this one the small 6-ton sloop PORTUGAL, was anchored inside the breakwater when her anchor cable parted. The sloop struck the breakwater and was about to go to pieces when the life savers arrived to save the fishermen. The vessel became a total loss at the breakwater.

April 28, 1923. Captain George Gardner was in command of the 678-ton, three-masted schooner barge BRADDOCK, en route from South Amboy, New Jersey, to Fall River, with coal on board. The barge was one of four being towed by the tug WATUPPA on a stormy night in Block Island Sound. When another barge in the string, RANDOLPH, developed trouble, it was taken into the safe waters behind Point Judith’s breakwater, while the remaining three barges remained offshore in rough waters. The WATUPPA immediately headed back to the other barges and managed to rescue the captains and crewmen of the barges CANTON and TAUNTON, while the storm continued to rage around them. Unfortunately, the BRADDOCK’s captain ran out of luck; he drowned when his barge ran on the rocks at Point Judith. The storm lasted fifteen hours and in the region at other locations killed a total of eight seamen and destroyed six vessels.

April 28, 1923. The 318-ton schooner barge TAUNTON, part of the string of barges with the BRADDOCK (mentioned above) met with a similar fate to that vessel. She was swamped and broken up on the rocks at Point Judith during a severe gale. But no loss of life was suffered.

June 5, 1934. The pleasure yacht MAXWELL, a 46-foot, 19-ton auxiliary sloop, became a victim of foggy conditions at Point Judith while en route from New York City to Gloucester, Massachusetts. Her crew of the owner and his assistant were accompanied by two artists who were bringing art supplies to Gloucester for an art school. The sloop struck on the breakwater in heavy fog and sank within an hour. All aboard made it to safety on the breakwater.

July 12, 1956. After more than twenty years of no losses at Point Judith, the diesel-screw powered fishing boat WILLIAM D., of New York City, became another victim of the breakwater wall at Point Judith. Although the cause of this disaster is not clear, her final voyage ended when she ran into the south section of the wall. She was a 39-ton vessel measuring 56 feet-in-length and was built in Fernandina, Florida, in 1943.

May 26, 1957. Another member of the Rhode Island fishing fleet, SHANGRI-LA, came to grief just 100 yards off the light house at Point Judith. She was 40-feet-in-length and displaced a mere 13-tons. She was owned by John E. Briggs of Providence; details of her loss have not come to light. She is reported in the Loss List of Merchant Vessels of the United States for 1958, which notes commercial vessels reported lost in the prior year.

March 24, 1963. The diesel-screw powered fishing boat HARVEST, bound from New Bedford for Groton, Connecticut, was lost at Point Judith. The boat’s new owner, Albert Nicolosi, was killed. He reportedly had just purchased the dragger was headed back on his vessel alone. Sometime before the boat ran onto the breakwater at Point Judith her owner may have abandoned her as his dory was later found about four miles away. No trace of his body was ever found and the exact reason for the disaster is unknown.

February 19, 2002. Almost forty years after the loss of HARVEST, the fishing vessel FORAGER, out of Galilee, on a fishing trip, was lost. On the morning of her sinking, the Department of Environmental Management was notified that the vessel was heading back to port as she had begun taking on water. She made it to the Harbor of Refuge where she sank. An unauthorized repositioning of the sunken vessel to more shallow water resulted in significant structural damage and substantial leakage of diesel fuel. In turn, this development led to the temporary closure of the Harbor of Refuge for fishing. As the weather deteriorated, the remains of the vessel began to break up. Only her engines and some flotsam from the wreck were recovered.

February 22, 2004. The steel hulled fishing vessel LADY HELEN made her final trip when inbound to Galilee. The exact cause of the disaster is not clear but the vessel sank in the vicinity of the gap between the west wall and center wall of the breakwater at Point Judith. Her fuel tanks were removed to prevent aggravated pollution of the waters in the Harbor of Refuge and what was left of the vessel was removed with the assistance of a crane barge.

May 19, 2008. Carrying a cargo of 13,000 pounds of squid, the diesel-screw powered fiberglass fishing boat BLUE SEA was inbound to Point Judith when a crewman fell asleep at the wheel. The 63-foot boat ran ashore about thirty feet northeast of the Coast Guard Station at Point Judith. Fortunately, no lives were lost. All of the appropriate agencies that deal with issues of pollution were alerted to remove diesel fuel and hydraulic oil from the wreck. After their efforts had been completed and any salvageable material retrieved, the vessel was determined to be a total loss.

May 27, 2010. The 31-ton diesel-screw powered fishing vessel LUCY M was, ironically, on its way from Galilee to Warwick for repairs when disaster occurred. Aboard the vessel were her master, Ralph Pearson, and one crewman. The boat began taking on water from a leak about a mile off Black Point at Narragansett. The Coast Guard responded to the scene and escorted the sinking vessel, as Pearson failed in attempting to beach the vessel on a shoal. The 51-foot-long, wooden hulled boat had seen service for more than fifty years, being launched in Essex, Connecticut, in 1945. The LUCY M sunk in the middle of the Harbor of Refuge in about 25 feet of water. Whether or not the wreck was removed is unclear.

As this series of articles continue, the next most prolific area for totally lost vessels in Rhode Island waters is Beavertail Point. At least 21 vessels have been known to have left their bones in the immediate vicinity of the point.

[Banner image: Point Judith Lighthouse in Narragansett at night (Sanford Neuschatz Collection)]