I have no idea exactly when during the mid-eighteenth century that Newport Philips entered this world but I do know the ”where” and the ‘what” of his beginnings. What he was, from the time of his birth, was a slave, and where he endured that servitude was on the enormous Philips farm centered around the manor house, called Mowbra Castle. The Philips family was among the landed gentry of the region. Although they are never mentioned as part of the Narragansett Planter elite, a class of successful dairy farmers in South County in the mid-eighteenth century whose members aspired to become aristocrats, I do not understand why not. The Philips’ landholdings in the eighteenth century were several hundreds of acres, the Mowbra Castle was arguably the largest and finest home on the West Bay, and finally, and most importantly, the family’s agriculturally focused business dealings were accomplished throughout the period with the support of slave labor. Newport Philips was one of those slaves.

Early on in his existence, no documents recorded the milestones of Newport’s life. With the exception of perhaps the financial ledgers of their owners or probate records (most of North Kingstown’s were destroyed by fire), such things were not deemed worthy of notation. But then in March of 1789, something quite remarkable occurred, something that the participants felt was worthy of recording in the permanent record of North Kingstown, and it was something actually worthy of a celebration. Newport Philips was set free.

How this came to come about is not certain. But we do know that in 1784, the Rhode Island General Assembly enacted a gradual abolition law: any slaves born after that time, once they reached adulthood, would become free. However, the law did not emancipate existing slaves, such as Newport.

But then something unusual occurred in South County, the former center of slavery in Rhode Island. Many owners of slaves voluntarily set them free. Why did this occur? The motives likely differed in each case. Certainly the ideas of freedom for all, as espoused in the Declaration of Independence, had permeated society by that time, and many did see the hypocrisy of continuing to hold slaves. In addition, with a decline in the state’s economy and division of Narragansett Planter estates, slavery was less profitable. Furthermore, some slaves and owners negotiated a deal: the slave would agree to work for a few more years and not try to escape, and then would be freed. Perhaps this is what Newport Philips agreed to with his master, Peter Philips.

Peter Philips presumably inherited Newport as property from his father, Samuel Philips, a Revolutionary War hero who had served as second-in-command to William Barton in the party that captured a British general in his bed in British-held Portsmouth in 1777. But Peter would not agree to free Newport himself. Instead, he agreed to transfer ownership of Newport to Beriah White, a Quaker. Quakers in South County had insisted on each of their members not holding any slaves well before the Revolutionary War. Peter probably made this arrangement because he did not want to liable for a bond that was required to be issued by a master freeing his slave, and apparently Beriah was willing to assume the burden from an interest in seeing that Newport become a free man.

Peter Philips presumably inherited Newport as property from his father, Samuel Philips, a Revolutionary War hero who had served as second-in-command to William Barton in the party that captured a British general in his bed in British-held Portsmouth in 1777. But Peter would not agree to free Newport himself. Instead, he agreed to transfer ownership of Newport to Beriah White, a Quaker. Quakers in South County had insisted on each of their members not holding any slaves well before the Revolutionary War. Peter probably made this arrangement because he did not want to liable for a bond that was required to be issued by a master freeing his slave, and apparently Beriah was willing to assume the burden from an interest in seeing that Newport become a free man.

In March of 1789, Peter, Beriah, Newport, and another slave owned by Peter, named Jack Philips, all went down to visit the Town Clerk in Wickford and proceeded to do something life changing for Newport and Jack—set the slaves free. The legal term for this is manumission. Beriah Waite filled out an order of manumission for Newport Philips, and Peter Philips did the same for Jack Philips. Additionally, Beriah and Peter each put up a $100 bond as a surety guaranteeing that Newport and Jack, respectively, would do nothing as free men to break the laws of the State of Rhode Island. Each document, recorded by Town Clerk George Thomas and witnessed by Benjamin Davis, mentioned “setting him free to his own use and liberty” done in “recognition and consideration of good servitude and labour.” This last mention suggests that perhaps Newport and Peter did strike some kind of deal for Newport’s freedom.

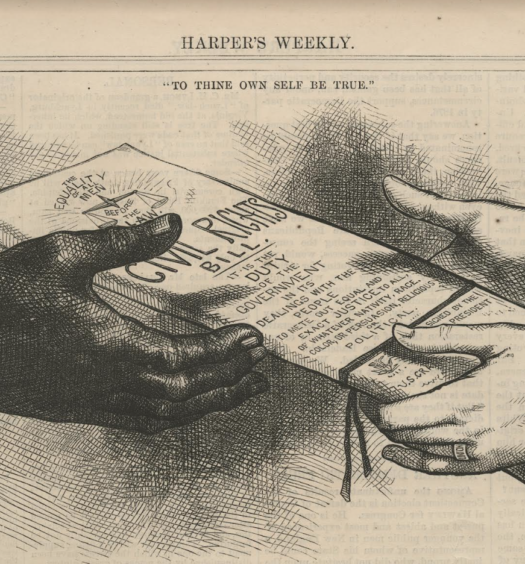

Under the laws of Rhode Island, Newport and Jack as of that day were free men entitled to keep for themselves whatever they earned from their own labor. It is likely that a copy of the manumission certificate was given to each man, who left the Town Clerk’s office grasping the most important piece of paper he would ever hold.

Newport seems to have stayed in North Kingstown for a time, but by 1800 he was living in Portsmouth, Rhode Island. As did many freedmen, he worked as a temporary farm laborer. At some point around this time, he met a slave woman named Margaret, who was owned by the wealthy Easton family of Portsmouth and Middletown. They fell in love and became man and wife, although due to Margaret’s continuing status as a slave no marriage was recorded. They had at least two children together, John and Phebe, and those children, due to the Rhode Island’s 1784 gradual emancipation legislation, were technically born free, although they were bound to their mother’s owner by the same law that stated her owner was financially responsible for them until they attained the age of twenty-one. Thus, in many ways, they were still slaves, if only temporarily. This though, did not seem to be the case by 1810, since the census of Portsmouth for that year shows Newport Philips as a free black heading a household with two other family members. Those two individuals most likely were John and Phebe. It appears that Newport and Margaret had somehow negotiated with the Eastons that he would care for their children while she would continue working for the Eastons.

By 1820, in the census records, Margaret shows up in Portsmouth as the head of a household with two children under her care. It might have been the case that her master allowed her to live independently, but still required her to do some work for him. Was this the result of another negotiation engaged in by Newport? At the time, Newport was back in North Kingstown, working again as a farm laborer, saving money, and planning something extraordinary. On April 1, 1824, Newport Philips, a free black man, having finally saved sufficient money, made his way to Middletown with his money to purchase the freedom of his wife of more than two decades. That transaction was recorded in the town ledgers of Middletown just as Newport’s manumission had been recorded in Wickford some thirty-five years earlier. Newport and Margaret Philips both left Middletown on that day free. What a glorious day that must have been for them.

This remarkable couple disappears from the historical records at this point; I don’t know when or where they breathed their last breaths; while they could have returned to North Kingstown, they probably remained in Middletown or Portsmouth since their children lived in the area. Their son John stayed on in Portsmouth and married Patience Sherman. They had at least more one child, James, together and John, who worked his whole life as a farmhand, died in 1876. James lived in Newport as an adult, had a wife named Louise, and worked as a fisherman until the end of his days. Newport and Margaret’s daughter Phebe eventually married Daniel N. Morse, a sexton at the Methodist Episcopal Church in Providence’s second ward. They had children together and she died in 1871. The slave Newport Philips lives on through the heirs of his children and grandchildren where ever they may be.

The old Philips family graveyard can be found in the midst of the Haverhill neighborhood off of Tower Hill Road on land that was once part of the vast Philips family holdings; in it stands a number of fine gravestones of this once important family. The slave graveyard of those same Philips’ is lost. It was last seen in the 1950s and was noted to include seventeen graves. Two of them, named Lonnon and Hagar, were inscribed with the phrase “servant of Christopher Philips.” Lonnon could have been Newport’s father or Hagar could have been his mother. Newport and Margaret may well be buried here or perhaps under a similar unmarked stone in Portsmouth. Where ever they are is of no real consequence I suppose; what matters is that they are together and forever free.

(banner image courtesy of Tim Cranston.

Bibliograpy

Town Clerk and Vital Records, Town of North Kingstown

Vital Records, Towns of Middletown and Portsmouth

Vital Records, Rhode Island State Archives, Providence

The Newport Mercury, April 13, 1872

Akeia A. F. Benard, “The Free African American Cultural Landscape: Newport, RI, 1774-1826,” Phd Dissertation, University of Connecticut, 2008

Christian McBurney, Jailed For Preaching, The Autobiography of Cato Pearce, A Slave from North Kingstown, Rhode Island (Kingston, RI: Pettaquamscutt Historical Society, 2006).