The use of facsimile currency for advertising purposes was not unusual during the nineteenth century, and such ephemeral items are known to exist from all areas of the country. One of the earliest examples of their use can be found in the promotion of the Clothing Bazaar on South Main Street in Providence, Rhode Island. The shop specialized in ready-made apparel at low prices.

The store’s first owner was Louis Lewisson, a Jewish immigrant from Prussian Poland. Arriving in Providence in 1845, he soon set up business at 31 South Main Street. He quickly relocated to 2 South Main Street near the Providence waterfront, where his clientele, unable to afford costly tailor-made apparel, found clothes within their price range.

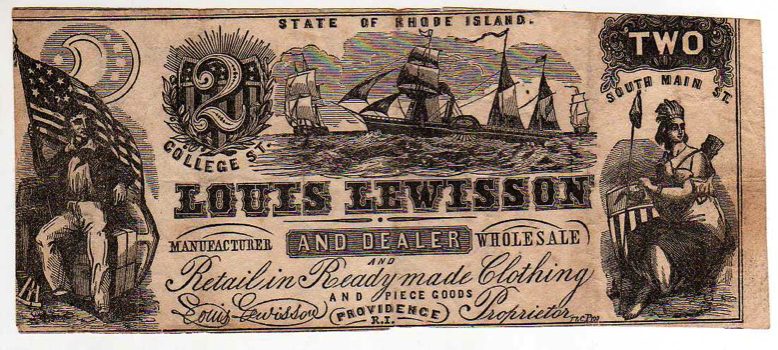

As one of the earliest Jewish merchants in Providence, Lewisson not only was a pioneer, but he also was an innovator in the use of facsimile currency for advertising purposes. (Figure 1) Competition for business was keen along South Main Street, with nearly a dozen similar clothing shops just minutes away. Wanting his business to stand out from the rest, Lewisson soon came up with the idea of issuing small advertising handbills.

Figure 1 – Entrepreneur Louis Lewisson’s Clothing Bazaar, a shop specializing in ready-made items at lower prices, issued facsimile currency in an effort to promote his business and stand out from his competitors.

During this period, state-chartered banks issued their own paper currency and were responsible for its design, printing and distribution. Lewisson, in a manner that would have impressed the famous entrepreneur and self-promoter P.T. Barnum, seized the opportunity and issued his own bank note styled advertising. The address of the Clothing Bazaar was prominently placed where an authentic note would display its denomination.

Like real, contemporary bank notes, Lewisson’s advertising piece was printed on one side only. To execute the design and engraving, he hired the Providence firm Thompson and Crosby, which was known for engraving many of the woodcuts used by local merchants on their stationary and in their newspaper ads. With its allegorical figures, elaborate ornamentation and signature block, the design Thompson and Crosby created for Lewisson’s facsimile note was similar in layout and size to most authentic bank notes of this period. However, it was pure fancy, with no known authentic paper currency exactly like it. Soon after the note’s issuance, Lewisson’s store moved again, requiring Thompson and Crosby to modify their design to reflect the shop’s new business address at 21-23 South Main Street.

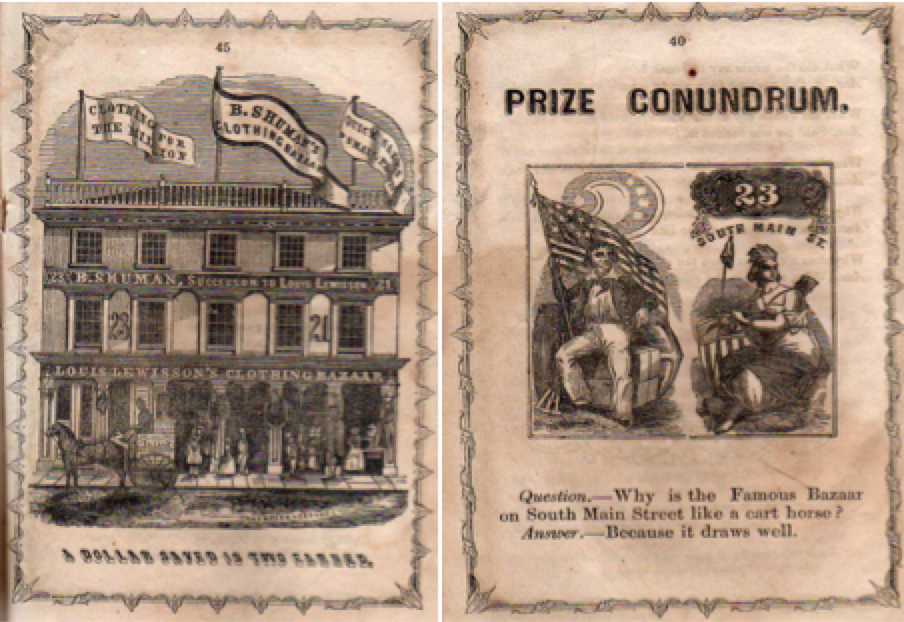

By the mid-1850s, Lewisson sold his business to Benjamin Shuman, who continued the business with the same ‘Clothing Bazaar’ name and at the same address. No slouch himself when it came to self-promotion, Shuman published an annual advertising booklet that featured vignettes originally shown on Lewisson’s facsimile bank note. The woodcut used in the booklet, which depicted the Clothing Bazaar’s façade, was modified to incorporate Shuman’s name on the flag atop the building. The second-floor sign-board that once read YOUTH’S AND CHILDREN’S CLOTHING was replaced with B. SHUMAN SUCESSOR TO LOUIS LEWISSON.(Figure 2)

Figure 2 – The woodcut Lewisson used in newspaper ads (left) was modified to incorporate new owner Benjamin Shuman’s name. Shuman used the images in his advertisement handbill for the Clothing Bazaar.

Lewisson first used the images on his store notes in the advertising pages of the 1852 printing of the annual Providence tax records. Presumably, Shuman appropriated them and asked Thompson and Crosby to make the necessary changes in the woodcut. Whether Shuman issued a facsimile bank note is uncertain, as none are known, but quite likely he did.

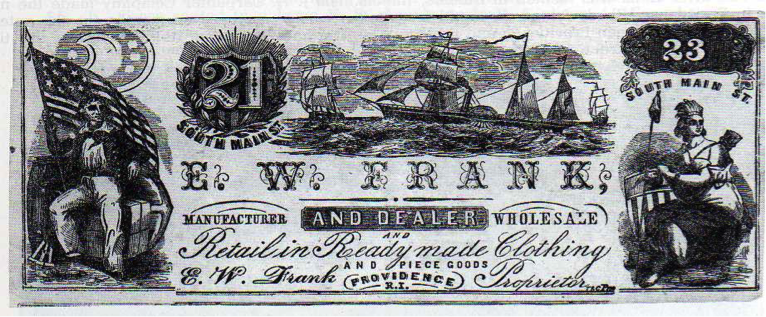

Shuman sold the store to Elisha W. Frank sometime in the early 1860s. Following in the tradition of his predecessors, Frank retained the name “Clothing Bazaar”; he also issued the same facsimile bank note modified only to accommodate his name. (Figure 3) Through intended as a stand-alone item, this note was reproduced in the 1861 printing of the Providence Business Directory. The back of the note is blank, while the one shown in the business directory bears an ad for another company. By the end of the Civil War, Frank sold the store to E. Spirling, but in less than two years time the Clothing Bazaar at 21-23 South Main Street was no more.

Figure 3 – The Clothing Bazaar’s facsimile bank note underwent another change in the early 1860s when Elisha W. Frank purchased the store. The new version, which prominently featured Frank’s name, retained the 21-23 South Main Street address.

The fortunes of business were serendipitous; Louis Lewisson, after selling out to Benjamin Shuman, left Rhode Island, only to return to Providence, where he dabbled in banking before re-entering the clothing business in 1859. His new store, called the “Clothing Warehouse,” was located on Market Square near his previous shop. It is unknown if Lewisson continued the practice of issuing facsimile bank notes to promote his store, since none are known for the Market Street address; however, after relocating to Worcester, Massachusetts in the early 1860s he again issued advertising scrip for his store located at 259 Main Street. The store was appropriately named the “Clothing Bazaar”.

As the Civil War drew to a close, the opportunity to use facsimile Confederate bank notes for advertising purposes became apparent. In Woonsocket, Seth Arnold, developer of the nationally renowned patent medicine Dr. Seth Arnold’s Cough Killer, used a Confederate $5 bill design for the face of his advertising note. (Figure 4) The image is that of the February 17, 1864 issue showing the Confederate capitol at Richmond, Virginia, along with a portrait of Confederate Treasury Secretary Christopher Memminger. Arnold’s note attempted to replicate the pink tone of the authentic note’s face. The back of the advertising note identified the Dr. Seth Arnold Medical Corporation. This note was issued no earlier than 1872, the year the business was incorporated.

![Figure 4 – Seth Arnold, a Rhode Islander and developer of a “cough killer” patent medicne chose a Confederate $5 note for the front of his company’s advertising issue. The back proclaimed Arnold’s concoction was “sure, quick and [a] perfectly safe remedy.”](http://smallstatebighistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/5-both.png)

Figure 4 – Seth Arnold, a Rhode Islander and developer of a “cough killer” patent medicne chose a Confederate $5 note for the front of his company’s advertising issue. The back proclaimed Arnold’s concoction was “sure, quick and [a] perfectly safe remedy.”

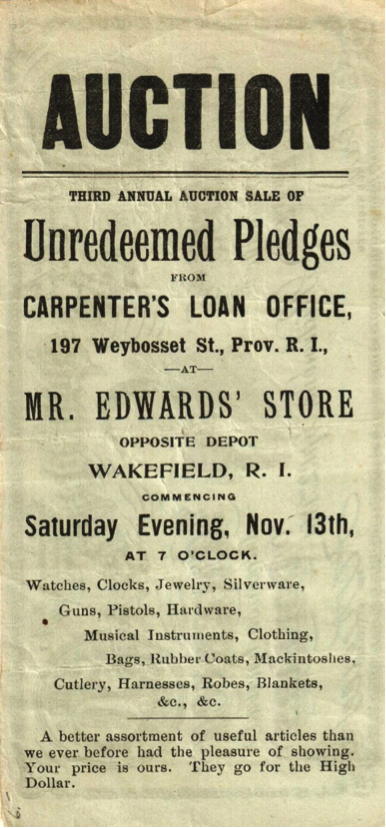

Figure 5 – Advertising issues that copied the images and designs used on Confederate notes were common. Carpenter’s Loan Office, a Providence pawnshop, used a portrait of Jefferson Davis on the face of a facsimile note that promoted one of its auctions.

The use of obsolete bank notes for advertising purposes faded into history following the Civil War. However, Confederate notes remained popular for this purpose even into the 20th century.

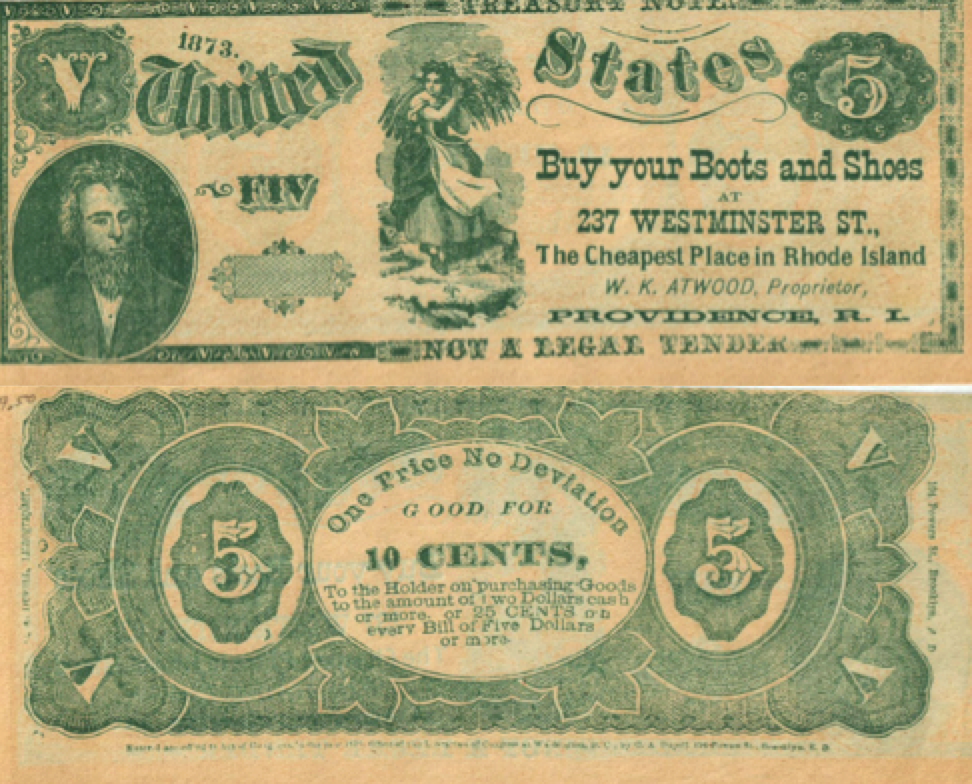

The year 1863 began the era of National Banks and a new opportunity to mimic greenbacks to promote private business was at hand. In 1873 Providence merchant William K. Atwood used a fanciful design to promote his boot and shoe business. (Figure 6) His notes served as a “good for” come-on, in this case 10 cents toward the purchase of merchandise totaling $2 or more, or 25 cents off a purchase of $5 or more. Printed by C.A. Dupell of Brooklyn, New York, the notes included the precaution that they were not legal tender, while misspelling (possibly with intent) the word “five”.

Figure 6 – William K. Atwood marketed his Providence boot and shoe business with a “good for” note, which in this case was 10 cents off of a purchase of $2 or more, or 25 cents on $5 or more. The word FIV on the front may have been intentionally misspelled.

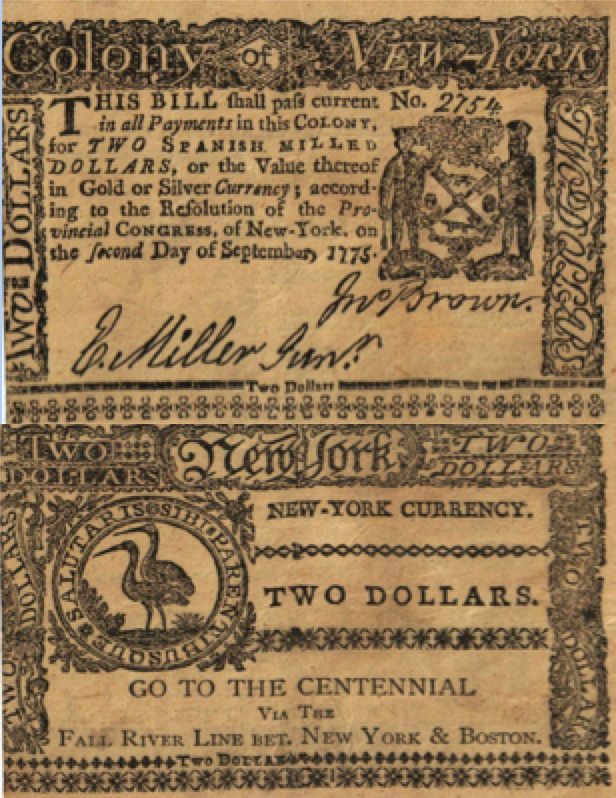

Also during the 1870s, the Fall River Line in commemoration of the 1876 U.S. centennial celebration issued an advertising piece resembling a colonial $2 note from New York. (Figure 7) The large steamship line provided service between New York and Fall River, Massachusetts and had a major port-of-call at Newport, Rhode Island.

Figure 7 – The Fall River Line steamship company commemorated the country’s centennial celebration using a facsimile New York colonial note.

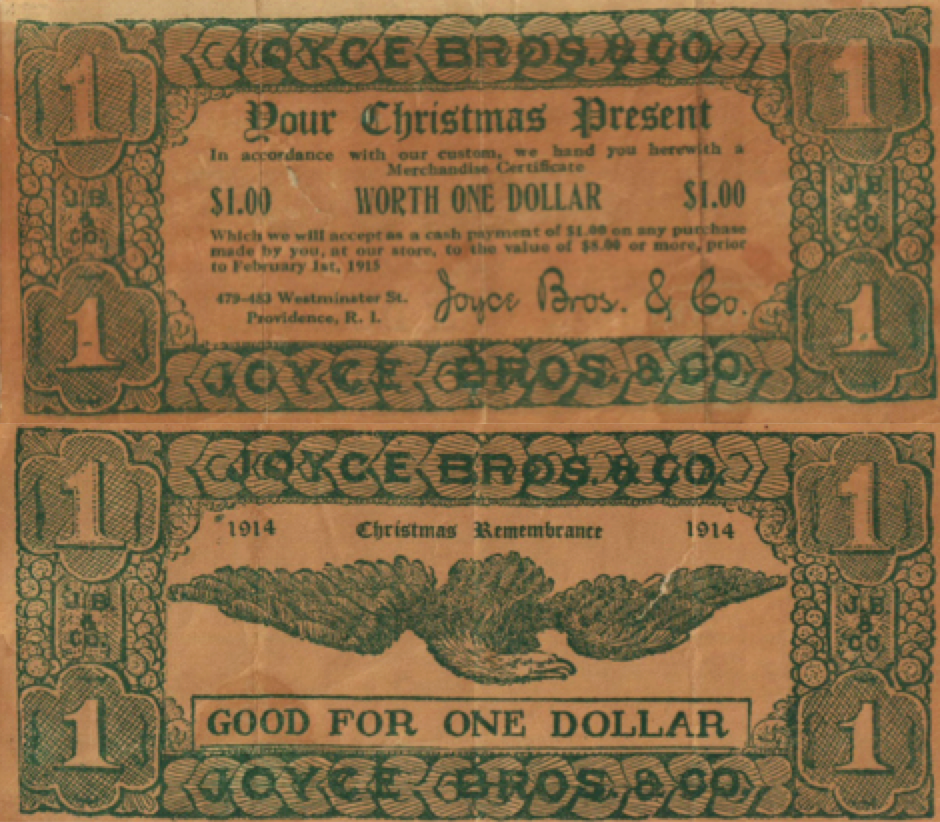

The early twentieth century saw the continued use of facsimile notes for advertising purposes, but the quality of these pieces was generally poor. With the approach of World War I, the Providence clothing and jewelry store, Joyce Bros. & Co., issued a 1914 Christmas remembrance “good for” $1 toward the purchase of merchandise valued at $8 or more if redeemed before February 1, 1915. (Figure 8) This note does not resemble any U.S. currency issued during this period and looks more like play-money than real currency.

Figure 8 – A 1914 Christmas “good for” note issued by Joyce Bros. & Co., a Providence clothing and jewelry store, offered customers $1 toward the purchase of $8 or more in merchandise.

During a span of just 75 years, Rhode Island businesses that promoted their stores and products managed to replicate the look of real money from the colonial period, state bank, Confederate and greenback periods. Today, examples of these issues often are more difficult to locate than the real notes they imitated and rivaling them in collecting interest.

Further Reading:

For a detailed look at advertising notes the standard work is Robert Vlack, An Illustrated Catalogue of Early North American Advertizing Notes (New York, NY: R.M. Smythe, 2001). While not focused on advertizing notes specifically but with a focus on Rhode Island obsolete currency and some advertising notes see Roger H. Durand, Obsolete Notes and Scrip of Rhode Island and The Providence Plantations (Roger h. Durand, 1981).