[Note from the author: This article is a slightly edited reproduction of my September 2019 welcoming address to the National Conference of the American Speakers of the House held in Newport and hosted by Rhode Island House Speaker Nicholas Mattiello. This article will be presented here in two parts (this is Part II). It is also available as an attractive pamphlet from the Rhode Island Publications Society (at www.ripublications.org.]

Theme #5 The Founding of the United States Navy

In December, 1774, after the burning of the Gaspee and the failed investigation into that act of rebellion, England dispatched the formidable 24-gun frigate H.M.S. Rose to patrol Narragansett Bay in search of Rhode Island smugglers. Its captain, James Wallace, greatly abused his regulatory powers, even raiding coastal farms for provisions and harassing lawful commerce. Feeling quite certain that Captain Abraham Whipple had led the Gaspee raid, Wallace said he would hang him. Hearing of this threat, Whipple sent Wallace the following message: “Sir, before you hang a man you first must catch him!” Whipple’s full-length portrait now hangs in the main building of the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis, appropriately named Bancroft Hall.

On June 12, 1775, Rhode Island responded to Wallace and the ships under his command by establishing a colonial navy, the first of the Revolutionary era. Three days later, its 10-gun Katy under Abraham Whipple captured the Diana, one of Wallace’s armed sloops.

In August 1775, the Rhode Island General Assembly urged Congress to create a Continental Navy. Then Stephen Hopkins persuaded the Continental Congress to follow Rhode Island’s lead. As the chairman of its Marine Committee, Hopkins introduced a bill to establish a U.S. Navy. It passed on October 13, 1775, with support from Silas Deane of Connecticut and John Adams and John Hancock of Massachusetts. Its first ship was the sloop Katy (renamed Providence), owned by John Brown, the leading Providence merchant and a business and political associate of Hopkins. This ship later became the first command of Captain John Paul Jones. By December, Hopkins’ committee had authorized 30 ships. Nearly half of the sailors and officers on them were Rhode Islanders.

Many of these naval vessels and American privateers would be outfitted with cannon and shot produced in Rhode Island. Here, again, Hopkins was involved. Since 1766 he had been a partner with John Brown in an iron smelting enterprise called Hope Furnace in Hopkins’s home town of Scituate. During its first decade, one of its prime customers was forgeman Nathanael Greene of nearby Coventry. When the American Revolution erupted, the company’s production gradually turned from pig iron to cannon and cannonballs. According to John Brown’s estimate, between 1778 and 1781 Hope Furnace produced about 3,000 high-quality cannons for naval and military use.

Replica of the sloop Providence sailing in Narragansett Bay in 1976, the year of the Bicentennial (Heritage Harbor Museum)

In December 1775, Hopkins, after a diligent search, chose his brother Esek, an experienced merchant and privateersman, as the U.S. Navy’s first commander-in-chief. Was this choice nepotism or brotherly love? Hopkins also initiated a move to authorize two battalions of men to serve as amphibious troops on navy ships. Thus, on November 10, 1775, in Philadelphia’s Tun Tavern, the U.S. Marine Corps assembled for their first recruitment drive.

Disregarding the wishes of Southern delegates to engage the British in the Chesapeake or off South Carolina, Hopkins took a small naval flotilla to the Bahamas in late winter 1776 and raided poorly guarded Fort Nassau on the appropriately named island of New Providence. His nearly unopposed raid of March 3, 1776, netted some cannon, munitions, and gunpowder. It marked the first military landing of the U.S. Marines—270 of them.

This fact should prompt revisions of the Marine Corps hymn: “From the Halls of Montezuma to the shores of the Bahamas”—a landing that occurred 29 years before the invasion of Tripoli.

This first American navy was greatly out-gunned and out-manned by England—the Mistress of the Seas. However, the heroic exploits of Scottish-born John Paul Jones, Irish-born John Barry, and Rhode Island’s own Silas Talbot have remained a part of our naval lore. Of the 13 American frigates built during the Revolution, 7 were captured and taken into the Royal Navy, and another 4 were destroyed to prevent their capture. In August 1779, the sloop Providence, after an impressive career, was scuttled in Maine’s Penobscot Bay to prevent its seizure by a blockading English squadron. John Barry’s flagship, Alliance, became the last vessel in the Continental Navy. It was sold to a private buyer in 1785 and later abandoned on a sand bar in the Delaware River. In the mid-1790s, under the leadership of Barry, the navy revived to combat attacks on American commerce by England, France, and North African pirates.

It is worthy to note that when a full-scale war with England erupted in 1812, Rhode Island produced the naval hero of that conflict, Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry. He was the son of Christopher Perry, a Revolutionary war mariner from South Kingstown, and an Irish immigrant mother whom Christopher met when a prisoner of war in Ireland. Perry decisively beat the British in the strategically significant Battle of Lake Erie on September 10, 1813, declaring “We have met the enemy, and they are ours!”

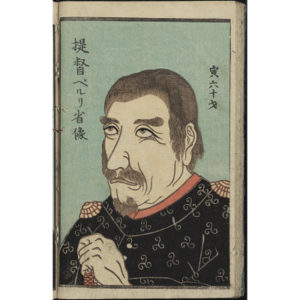

To further enhance Rhode Island’s pioneering naval heritage, Oliver’s younger brother, Commodore Matthew Cailbraith Perry, used knowledge gained as a native of America’s most industrialized state to become the reputed “Father of the American Steam Navy.” Not only did Perry lead the transition from sail to steam power, but he also used the navy as a diplomatic device to open Japan to western trade and influence in 1854.

With the foundation of the U.S. Naval Academy in 1845 by four-decade Newport summer colonist, George Bancroft and the establishment there in 1884 of the U.S. Naval War College by Admiral Stephen B. Luce, a long-time Newport resident, Rhode Island never lost its naval primacy.

Theme #6 The Constitution

Although Rhode Island was among the first in war, it was undeniably last in peace. The same doctrines that I have described—religious freedom, democracy, federalism, and local autonomy—with which Rhode Island influenced American development, kept the newly independent state from attending a convention that it felt might replace one strong, remote central government, just deposed, with another.

Rhode Island quickly ratified the nation’s first Constitution, the Articles of Confederation. That document exalted state sovereignty and created a weak central government with little coercive power or financial resources. Each state had a veto on legislation, and Rhode Island exercised its veto early by opposing the proposed Impost, or Tariff, of 1781, a measure that would have given the central government a significant source of revenue.

When the so-called Founding Fathers properly moved to strengthen the central government via a convention called merely to amend the Articles, Rhode Island declined to attend. When that 1787 Convention produced a new Constitution (thanks to James Madison), Rhode Island refused to ratify it. One reason for Rhode Island’s obstinacy was purely local. In 1786, an agrarian political uprising led by Jonathan Hazard of Charlestown placed the Country Party in power. Their campaign was based upon the promise to relieve debtor farmers who were in danger of losing their property for non-payment of taxes on land imposed by the merchant-controlled legislature to pay the principal and interest on state and national war bonds held mostly by these merchants.

The Country Party immediately authorized the issuance of £100,000 of paper money that could be borrowed by the farmers and secured by their land. With that money, which was legal tender, they could pay their public and private debts. The local merchants and the Founding Fathers were horrified by this clever scheme. The state was called “Rogues’ Island,” where democracy had run rampant. “Nothing exceeds the folly and wickedness that exists there,” asserted an exasperated Madison. With Rhode Island in mind, the Constitution’s Article I, Section 10 prohibited the states from issuing paper money, so Rhode Island waited until its currency plan had run its course and achieved its intended effect.

The Country Party attempted to compel creditors to accept its paper money by imposing penalties for refusing it. Its Force Act of 1786 denied trial by jury to the violators. General and attorney James Mitchell Varnum challenged this statute in the landmark case of Trevett v. Weeden (1786) by writing a compelling argument that advanced the doctrine of judicial review. He called on the court, which ultimately refused jurisdiction of this hot issue, to declare the Force Act an unconstitutional deprivation of the right to trial by jury. Varnum then published his legal treatise and distributed it in Philadelphia just prior to the Constitutional Convention. Legal scholars regard Varnum’s argument a significant precedent for the establishment of this major constitutional doctrine by Chief Justice John Marshall in the case of Marbury v. Madison (1803).

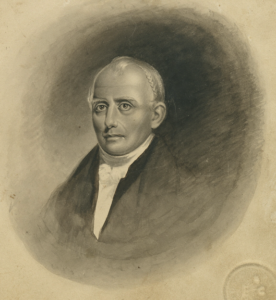

General James Mitchell Varnum of East Greenwich was the prime mover during the Revolutionary War in the creation of Rhode Island’s famed “Black Regiment” of formerly enslaved men and other men of color. His argument as a lawyer in the case of Trevett v. Weeden developed the crucial doctrine of judicial review of legislation to insure the legislation complied with constitutional mandates. He died and was buried at Marietta, Ohio, in January 1789 at the outset of his attempt to organize and settle the Northwest Territory. (Independence Hall)

But Rhode Island had nobler reasons for resisting the new United States Constitution: (1) it lacked a Bill of Rights; (2) it thrice gave assent to slavery—in Article I, Section 2, the Three-fifths Clause, relating to representation in the House; in Article I, Section 9, the 20-year moratorium on any federal law banning the foreign slave trade; and in Article IV, Section 2, the Fugitive Slave Clause; (3) it threatened state sovereignty; and (4) it specified the use of a convention rather than a popular referendum for ratification. In defiance of that requirement, Rhode Island held its own referendum in March 1788. With the Constitution’s supporters, called Federalists, boycotting the balloting, the proposed basic law was rejected by a vote of 2,714 to 238—a margin of 11-to-1.

When George Washington was inaugurated on April 30, 1789, Rhode Island and North Carolina were still outside the Union. Both states were then controlled by similar democratic grassroots populations. In fact, when Carolina was split into north and south in 1729, some observers referred to the new state as “a vale of humility between two mountains of conceit” (Virginia and South Carolina).

Under strong federal and internal pressure, Rhode Island finally called a ratifying convention in January 1790 by a 1-vote margin. The first session met in South Kingstown in March and adjourned until May after offering 36 amendments to the new basic law.

Enraged Federalists threatened Rhode Island with tariffs and made other financial demands, and Providence threatened to secede from the state if ratification did not occur. This pressure brought compliance. On May 29, 1790, Rhode Island ratified the Constitution by a vote of 34 to 32, the narrowest margin of any state. This approval was accompanied by 21 suggested amendments to that founding document.

One of Rhode Island’s proposed amendments (shared with North Carolina) sought to limit the jurisdiction of federal courts. The original Constitution contained a provision allowing a state to be sued in federal court by a citizen of another state. When the U.S. Supreme Court upheld this procedure in 1793 via its ruling in the case of Chisholm v. Georgia, a movement began to limit that aspect of federal court jurisdiction. This effort succeeded in 1795 with the ratification of the Eleventh Amendment. Rhode Island’s position prevailed.

When one considers the basis of Rhode Island’s disapproval of the original Constitution—resistance to an overweening and unrestrained central government; concern for the sovereignty and integrity of the states in the spirit of true federalism; solicitude for individual liberty, especially religious freedom; opposition to slavery and the incidents of servitude; and concern for democratic participation via referendum in the Constitution-making process—perhaps Americans might ask not why it took Rogues’ Island so long to join the Union, but rather why it took the Union so long to join Rhode Island. The future course of American History has vindicated Rhode Island’s obstinacy and resistance.

Theme #7 Expansionism

Clearly, expansionism was a major theme in American history, motivating the first settlers in Virginia and Massachusetts in the early 17th century and continuing unabated thereafter. By the mid-19th century, most Americans considered expansion to be the nation’s “Manifest Destiny.” Ultra-nationalists believed that American expansion, encompassing the continent from sea to shining sea, was divinely ordained as a method of spreading the nation’s democratic institutions.

The amazingly perceptive French visitor Alexis de Tocqueville, whose tour of America produced his revealing and accurate book Democracy in America, observed this drive in the 1830s. In one passage of that famous tome, he compared U.S. expansionism to that of Russia—one moving inexorably westward, while the other had moved eastward through Siberia to Alaska. He stated ominously that “their starting point is different and their courses are not the same, yet each of them seems marked out by the will of Heaven to sway the destinies of half the globe.”

The Robert Gray house on Main Road in Tiverton where Robert Gray was born in 1755 (Providence Public Library Digital Collections)

More than four decades before de Tocqueville’s astute observation, an American merchant-navigator had initiated contact with that expanding Russian empire in the Pacific Northwest. That intrepid seaman was Robert Gray of Rhode Island, born into a farm family in Tiverton on May 10, 1755. Gray’s homestead still stands on Tiverton’s West Main Road.

After naval service in the American Revolution, he entered the merchant trade. By September 1787, he left Boston for Canton, China, on a two-ship voyage of commerce and discovery with Captain John Kendrick. This expedition began three months before Rhode Island entered the exotic China Trade when leading Providence merchant John Brown and his son-in-law Joseph Francis sent their ship General Washington to the Celestial Kingdom with a cargo of rum, cheese, spermaceti candles, and cannon from Hope Furnace. Their vessel returned to Providence on July 2, 1789 laden with tea, gunpowder (which the Chinese invented), silk, flannel, porcelain, and a small fortune in profits for its investors.

Since the pioneering voyage to Canton of the ship Empress of China in 1784, it had been known that the Chinese desired the medicinal herb ginseng, harvested by Native Americans in the eastern forests and fields. Therefore, Captain Gray took a cargo of ginseng, and, with Kendrick, went to the Pacific Northwest to trade the natives there for sea otter and beaver pelts—other commodities valued by the Chinese.

On August 12, 1788, Gray and his crew became the first American citizens to land on the northwest coast. After that historic first, near Cape Lookout, Oregon, Gray proceeded to China, where he traded ginseng and pelts for tea, ceramics, porcelains, silk, and artworks. He certainly obtained a favorable balance of trade.

Gray chose a different route home—via the Indian Ocean and around Africa’s Cape of Good Hope. He arrived back in Boston on August 10, 1790, completing the first American circumnavigation of the globe. (N’orwest John DeWolf of Bristol completed the first overland circumnavigation via a trip across Siberia, returning to his hometown on April 1, 1808, 44 months after his departure for the Pacific Northwest on the ship Juno.)

Gray’s significance for America is far greater than one amazing voyage. On September 27, 1790, he left for the northwest again with letters from President Washington and Secretary of State Jefferson, whom he had notified in 1790 of his initial landfall.

Robert Gray’s ship Columbia at the mouth of the Columbia River, painting by Fred A. Cozzens (New York Public Library Digital Collections)

After cruising the northwest coast and wintering there in 1791–92, Gray made a final coastal excursion. On May 11, 1792, he guided his vessel through shoals into the mouth of a legendary great river, which he named “Columbia” for his ship. He spent nine days in the river, but only sailed 13 miles inland (of its 1,243-mile length) because of its shallow depth.

By these two voyages Gray established the first American claim to the Oregon Country. These visits intrigued the expansionist Jefferson, who dispatched Meriwether Lewis and William Clark with instructions to go beyond the Louisiana Purchase to the Pacific, where they established Fort Clatsop in 1805 at the mouth of the Columbia. These explorers were followed by John Jacob Astor in 1811 in search of furs. Oregon amply honors Lewis and Clark and has a major city named Astoria (pop. 10,000), but no city or county is named for Gray in Oregon, Idaho, or Washington, except for Gray’s River, Grayland, and Gray’s Harbor County in Washington. But, if not for Gray’s initiatives from 1788 to 1792, the residents of Washington, Oregon, and Idaho might be singing “God Save the Queen” rather than “God Bless America,” because British explorers Captain James Cook, George Vancouver, and Simon Fraser would have prevailed in securing all of the Pacific Northwest for England.

Theme #8 The Beginnings of America’s Industrial Revolution

On December 20, 1790, within 7 months of its admission to the Union, Rhode Island, a leader in the American War for Independence, led another revolution—America’s Industrial Revolution. With due deference to Paterson, New Jersey, and Lowell, Massachusetts, America’s Industrial Revolution began in Rhode Island via Samuel Slater’s act of “industrial espionage” in the North Providence village of Pawtucket.

England had a legal ban against exporting their manufacturing technology (heavy fines and a year in prison). However, in 1789 Pennsylvania offered a bounty to any English immigrants who would bring “English models for textile production” to that state.

In defiance of English law, Slater built a replica of Richard Arkwright’s water-powered cotton-spinning machine in Pawtucket, from memory. (Surprisingly, Slater’s birthplace, the town of Belper in Derbyshire, England, and Pawtucket are now sister cities.)

Slater, attracted by the bounties Americans offered to English workers skilled in the manufacture of cotton, was lured to Rhode Island in 1789 by Moses Brown and William Almy (Brown’s son-in-law). America produced great quantities of raw cotton, which, prior to 1790, it exported to England. On December 20, 1790, Slater spun cotton yarn by water power for the first time in America.

Samuel Slater, who has been called “the Father of American Manufactures.” Providence’s Moses Brown attracted him to Rhode Island (National Portrait Gallery)

Samuel Slater gave America the ability to manufacture cotton cloth on a large scale. In his landmark 1791 Report on Manufactures, Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton acknowledged the primacy of Slater’s Mill. President Andrew Jackson later called Slater “The Father of the American Industrial Revolution.”

Another aspect in the development of America’s cotton textile industry also has a Rhode Island connection. In 1792 Massachusetts-born Yale grad Eli Whitney journeyed south to Georgia to find work as a teacher. He met up with a New Englander Phineas Miller, also a Yale grad, who tutored the children of Catherine Littlefield Greene of Block Island, Rhode Island. Caty was the widow of General Nathanael Greene, who had been awarded a plantation near Savannah called Mulberry Grove. That gift from the state of Georgia was in gratitude for Greene’s heroic services to the South during the American Revolution.

Whitney, who was also a handyman, helped around the plantation and worked with Miller and with Caty Greene in the development of the cotton gin, an invention that Whitney patented in 1794. This project was Caty’s idea: she financed it and received some of its royalties.

The gin rapidly separated the seeds from green-seed cotton, grown in the interior South, which were much more difficult to remove than the black seeds in coastal cotton. This invention led to a vast increase in the production of raw cotton destined for Slater’s Mill and other northern factories. It also stimulated the expansion of cotton cultivation in the South. Here, again, a Rhode Islander played a major role in this important nation-changing economic innovation.

Slater Mill Historical Site, home of the first water-powered cotton spinning mill in North America to use the Arkwright system of cotton spinning as invented by England’s Richard Arkwright and developed by his protégé Samuel Slater in Pawtucket. He initially hired children and families to work in his mill establishing a pattern in Blackstone Valley and the rest of New England known as the “Rhode Island System.” (Wikipedia)

Concluding Observations

In the year 1790, as Robert Gray returned from his first circumnavigation of the globe on August 10 and Samuel Slater started his textile machinery on December 20, the United States was completing its first decennial census. That compilation counted 3,929,214 Americans, of whom 68,825 were Rhode Islanders—only 1.75 percent of the population. Just one in 57 Americans were Rhode Islanders. Yet look what they accomplished!

Such achievements bring to mind the tribute given by British romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley to Egyptian pharaoh Ramesses II when an ancient statue of that king was placed in the British Museum. Gazing upon it, Shelley was moved to write the poem “Ozymandias,” in which he had Ramesses speak these words: “Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!” Perhaps tiny Rhode Island could justifiably utter this challenge to its larger and better known sister states.

[Banner image: Slater Mill Historical Site, home of the first water-powered cotton spinning mill in North America to use the Arkwright system of cotton spinning as developed by England’s Richard Arkwright and copied by his protégé Samuel Slater in Pawtucket. Slater initially hired children and families to work in his mill establishing a pattern in New England known as the “Rhode Island System.” (Wikipedia) ]