It should come as no surprise, considering its rich maritime history spanning almost 400 years, that Rhode Island has had numerous marine disasters. As you might suspect, both sailing vessels and engine-powered vessels have been involved. This discussion concerns our state’s greatest marine disasters affecting steamships. I have selected loss of life to be the criterion used, but the argument could be made that in many notable disasters no lives were lost. That said, loss of life during a marine disaster is, without question, the most serious aspect of the disaster.

These summaries of the eight greatest steamship maritime disasters in Rhode Island history are presented in order of the severity in terms of loss of life, from the least severe, the collision between the freighter GRECIAN and the liner CITY OF CHATTANOOGA with the loss of just four men, to the most severe, the collision between the sidewheel steamer LARCHMONT and the schooner HARRY P. KNOWLTON in which more than 150 lives were lost. In five of the eight disasters, vessels collided. Another involved a boiler explosion. One was a vessel torpedoed during World War II. Finally, one involved the disappearance of both the ship and its entire crew, probably due to foul weather.

On May 27, 1932, the Merchant & Miners Transportation Company’s freighter GRECIAN was making her way southbound from Boston for Norfolk and found herself caught in a typical New England fogbank, with a heavy sea running. On a northbound track, the Savannah liner CITY OF CHATTANOOGA was headed for Boston, having left New York earlier in the evening, and was facing by the same challenging weather. Just before 2 a.m., the Savannah liner struck the freighter when both were a short distance south of Block Island’s Southeast Light. In short order, the 4,300-ton liner smashed the hull plates on the 2,800-ton freighter and within minutes the GRECIAN sank carrying four of her ship’s complement of thirty-six men to their graves. This type of incident was not uncommon in the days before modern electronics; such occasional accidents were in some ways inevitable. The site of the sinking was about five miles south of the light, an area heavily trafficked by vessels of all shapes and sizes and where minor collisions were all too commonplace. This one involved two large ships.

The steamer GRECIAN was run into and sunk by the liner CITY OF CHATTANOOGA off Block Island on a foggy day in the late spring of 1932.

Perhaps the most mysterious fatal voyage that has ever taken place in Rhode Island waters involved the 97-foot long, 165-ton steam tug WILLIAM MALONEY, lost with her entire crew of eleven men while in transit from New London to Newport. The tug was originally built in Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, in 1891 under the name JOHN L. CANN. In 1918, she was sold to parties in the United States and renamed CAPITOL NO. 1. Four years later, in February of 1922, she was seized from rumrunners. After that, her ownership became a bit obscure but it is believed that she was reacquired by rumrunners (perhaps the same ones who previously owner her) and renamed WILLIAM MALONEY shortly before her loss. Rumors of her use for illegal purposes were rampant; she was suspected of being the point of contact between ships on “Rum Row” and a New York bootlegging coterie. The weather had been stormy for several weeks before the final voyage of this thirty-three year old vessel. Exactly what happened to her and where is not known. She was not even reported missing for a week after her supposed loss date of November 15, 1924. The kin of the men lost on the WILLIAM MALONEY reported the loss to the Coast Guard, which previously had not known of the sinking. The news accounts speculated that she went down with contraband worth $400,000, but that allegation was never proved. It is possible that she was captured and intentionally sunk and the entire crew killed by rival rumrunners for the prized illicit cargo, but that also is speculation. Only discovery of the wreck site may prove or disprove all of the theories.

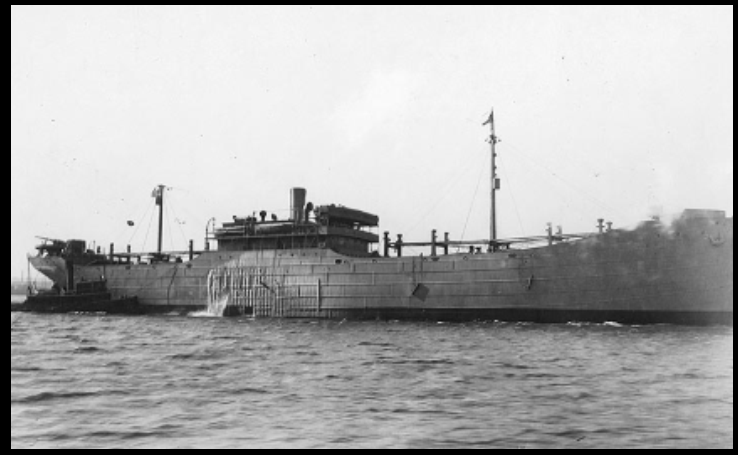

We can only imagine the irony of the loss of thirteen crewmen aboard the collier BLACK POINT who may have been chatting about the end of the war with Germany when their ship was struck by a single torpedo and sunk shortly before dusk on May 5, 1945. The New York Times reported that the bold daylight attack took place just twenty-seven hours before Germany surrendered. The question remains whether or not the captain of the German submarine U-853, the protagonist in the sinking, was aware that the war was essentially over and that a recall of all U-boats and cessation of hostilities by them had been sent out by radio a few days earlier. Thirty merchant seaman and four members of a Navy armed guard escaped into lifeboats from the 5,300 ton freighter just before she sank within three miles southeast of Point Judith. The BLACK POINT was launched in 1918 in Camden, New Jersey, as the FAIRMONT and also carried the name NEBRASKAN during her twenty-seven year career at sea. When sunk it was carrying 7,500 tons of coal from Newport News, Virginia, to Boston Edison’s power plant at Weymouth, Massachusetts. The wreck can still be visited today by scuba divers as it lies in two parts on the ocean floor. (U-853 itself was sunk by U.S. Navy destroyer escorts off about six miles north of Sandy Point on Block Island shortly after it torpedoed the BLACK POINT, with all fifty-five German submariners losing their lives. It is not included in my list only because it was a submarine and not a steamship.)

The BLACK POINT was the last merchant ship lost to a German submarine during World War II when she was sunk by a single torpedo from U-boat 853. Within hours of the sinking, the submarine was destroyed off Block Island with the loss of her entire 55-man crew.

In the annals of ironic incidents, the loss of the Ferro-cement steamer CAPE FEAR, on October 29, 1920, after a collision off Castle Hill, offers a unique story. The idea of building a freighter out of cement was not entirely new but, in this case, was pursued due to a shortage of steel during World War I. The 266-foot long vessel weighed in at less than 2,800 tons but proved to be no match for the Savannah Line steamer CITY OF ATLANTA, whose steel bow cut the CAPE FEAR almost in two. The cement steamer had departed the port of Providence headed south toward Norfolk without cargo. The CITY OF ATLANTA was inbound from Savannah for Providence with a load of pig iron when the two ships met for the first and last time. It was reported that the weather was clear with only slight cloudiness and a light sea running when the collision took place. Investigation into the sinking resulted in charges being brought against Harry A. Biggins, master of the lost vessel. He had discharged his pilot before leaving the confines of Narragansett Bay and changed the course of the CAPE FEAR after signaling to pass in another direction. As was the case with most of the Ferro-cement freighters built, the CAPE FEAR lasted less than a year from launching to sinking, and her loss with seventeen members of a crew of thirty-four in less than three minutes earns her a place among the greatest marine disasters in Rhode Island’s history.

One of only a handful of “cement ships” built at the end of World War I, the CAPE FEAR was lost with half of her crew on October 29, 1920, when she was less than a year old.

The distance between Jamestown and Newport is narrowest at the entrance to the East Passage into Narragansett Bay, and with vessels traveling inbound and outbound at all times, passing through this narrow channel is somewhat like threading a needle. At 6:57 a.m. on the morning of August 7, 1958, the 260-foot long, 1,500-ton tanker S.E. GRAHAM was headed inbound for Providence from Newark with a cargo of 900,000 gallons of gasoline. The much larger 400-foot tanker GULF OIL was outbound on a voyage to Port Arthur, Texas for another cargo after having discharged 114,000 barrels of oil at the port of Providence. In the dense fog the GULF OIL struck the S.E. GRAHAM on the port bow, just aft of the forecastle, opening the No. 1 wing tank. Immediately the smaller tanker burst into flames between Bull Point, Jamestown, and Fort Adams, Newport. Although empty, the GULF OIL was covered with burning gasoline from the S. E. GRAHAM and was forced to run ashore on the west side of Fort Adams. The S.E. GRAHAM, a mass of flames, drifted ashore on the southeastern part of Rose Island. A fleet of vessels from the Navy, Coast Guard and civilian entities immediately responded to the scene, and daring rescues were performed as burned crewmen leaped or slid into the water from the two stricken tankers. A total of twenty-three crewmen from the two vessels tragically lost their lives in the disaster. Neither vessel was lost in the incident but the S.E. GRAHAM was sold for scrap after the collision and fire. The GULF OIL was pulled offshore and sold shortly thereafter. Her hull was sound, so she was rebuilt and continued to sail in the Great Lakes as late as 2006.

On August 18, 1925, a marine disaster occurred the likes of which has never happened before or since in Narragansett Bay. Six hundred and seventy seven passengers had departed from Pawtucket on an excursion aboard the steamer MACKINAC. They reached their destination, Newport, and spent a few delightful hours sightseeing and visiting the local shops. A little before six o’clock the steamer cast off for the return trip with jubilant passengers ready to head home. The 162-foot long, 512-ton steamer had just passed the Naval Training Station on Coasters Harbor Island and was opposite Coddington Cove when, without warning, her boiler exploded. The lower decks instantly filled with steam from the engine room, and the screams of men, women and children being scalded to death filled the air. Almost instantly naval forces in the area sprang into action and headed for the stricken vessel, which in the meantime had been steered to the shore by her quick thinking master, Captain George McVey. In total, more than 100 persons were killed or injured; one source reported 55 souls lost. The follow-up investigation concluded that an old and defective boiler caused the disaster. The vessel itself was not materially damaged other than to the decking and engine room but was nonetheless sold to help cover the expense of the claims of the lost and injured, which were reported as $918,000.00. Unfortunately for the claimants, the sale of the steamer brought only $10,000.00to be split among all of the victims of the disaster.

Although it was unusual for ships built on the Great Lakes to be used in open water service, the MACKINAC was so employed. A boiler explosion cost the lives of more than 55 passengers off Newport (Providence Public Library Digital Collections).

The second greatest maritime disaster in Rhode Island waters took place seven years after the Civil War. The 1,300-ton wooden-hulled sidewheel passenger steamer METIS, owned by the Providence and New York Steamship Company, was sailing eastbound for Providence. She carried 110 passengers and 45 crewmen plus a cargo of fruit and cotton valued at about $50,000. The weather was rainy with a slight breeze, not an unusual weather pattern for a late summer’s night. Westbound in Block Island Sound at the same time was the 92-ton schooner NETTIE CUSHING, from Thomaston, Maine, headed for New York City. The weather became thick as the steamer entered Block Island Sound and visibility was reduced to about a mile. Although the lights on the approaching schooner were spotted when a half-mile separated the two vessels, and that sighting was reported to the pilothouse on the METIS, the collision still occurred. It may have been from the arrogance of steamer’s helmsman relative to sailing vessels interfering with his course or an error on the part of the schooner’s captain. Regardless, the schooner struck the side-wheeler on the port side about forty feet from the stern and then fell astern of the still-moving steamer. Captain Burton of the METIS immediately called for an investigation of the forward areas by suspending a crewman over the side with a lantern; when the crewman spotted no sign of serious damage the captain decided to continue on his trip. Very soon he realized that they were, in fact, taking on water as the bow was dipping lower and lower into the sea. In a later investigation, it was determined that the point of the collision was in the area between the two forward bulkheads, an area that had not been inspected, and as the water rushed in, its weight caused the third bulkhead, protecting the engine room, to collapse. This collapse caused a loss of the ship’s power.

The side-wheel steamer METIS sunk in Block Island Sound after being struck by a sailing vessel with the loss of at least 50 passengers. Another 40 passengers survived only by the good fortune of the hurricane deck breaking free of the hull and drifting ashore at Watch Hill.

It was now clear that the METIS was going down. Those who could swim took their chances with the sea; those who could not crowded onto the highest point of the vessel, the hurricane deck, and awaited their fate. Suddenly what could only be called a miracle occurred and the hurricane deck, along with almost forty passengers, broke free of the lower hull. After drifting around for some time on this would-be raft, the deck washed ashore at Watch Hill where onlookers rushed into the water to save those who had made it that far. The volunteer crew of the Life-Saving Service and local fishermen took two rowboats out into the surf to rescue victims, saving some 32 lives. The exact loss of life aboard the METIS is not known but the estimate placed the number at more than fifty. The date was August 30, 1872, and the collision took place at about 3:30 in the morning. Those on the floating deck, after experiencing a harrowing four-and-one-half-hour trip, were rescued at Watch Hill at about 8:00 a.m.

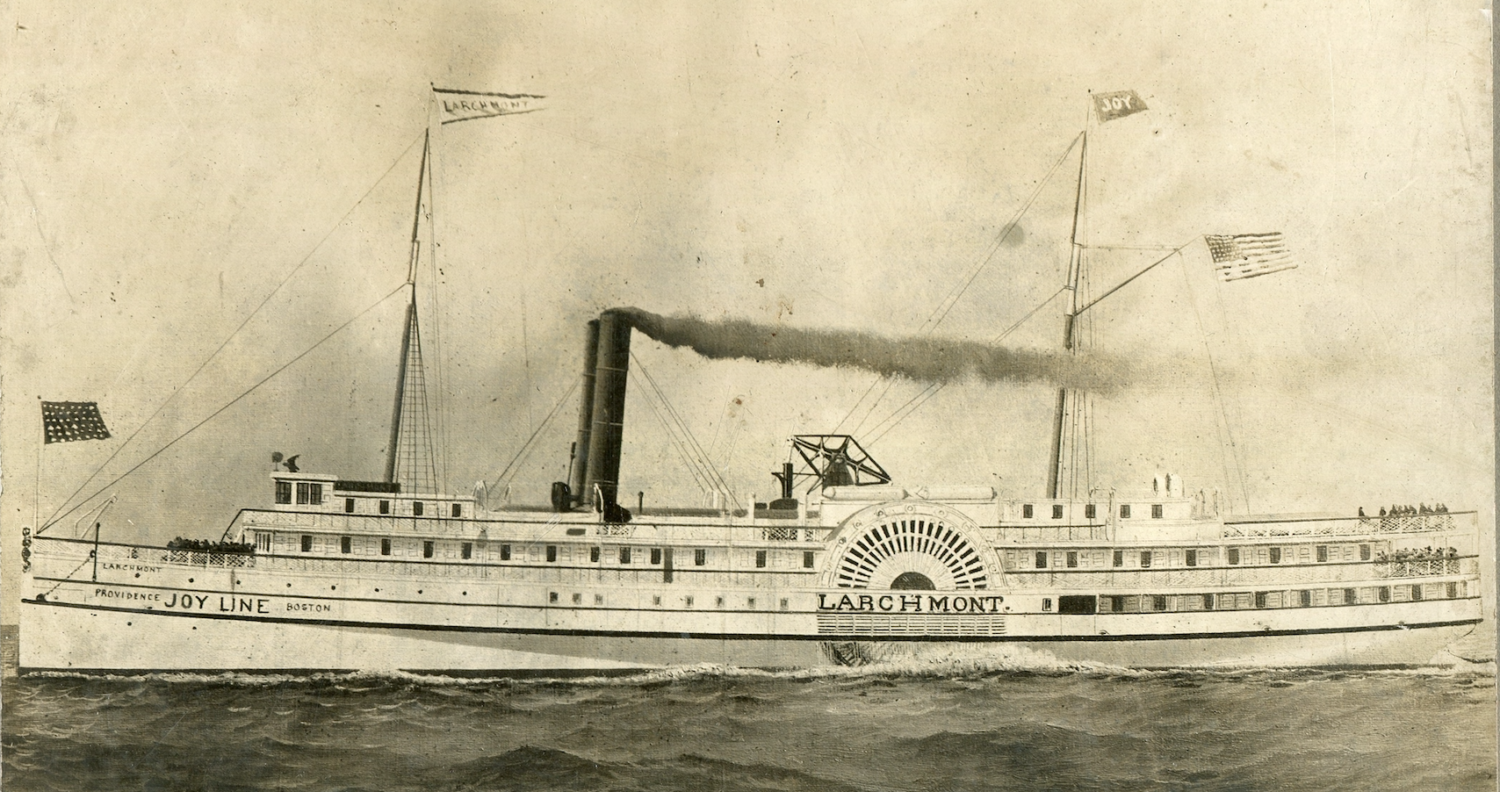

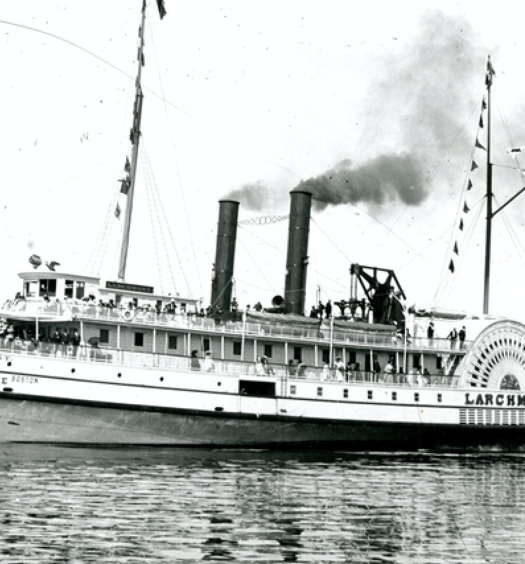

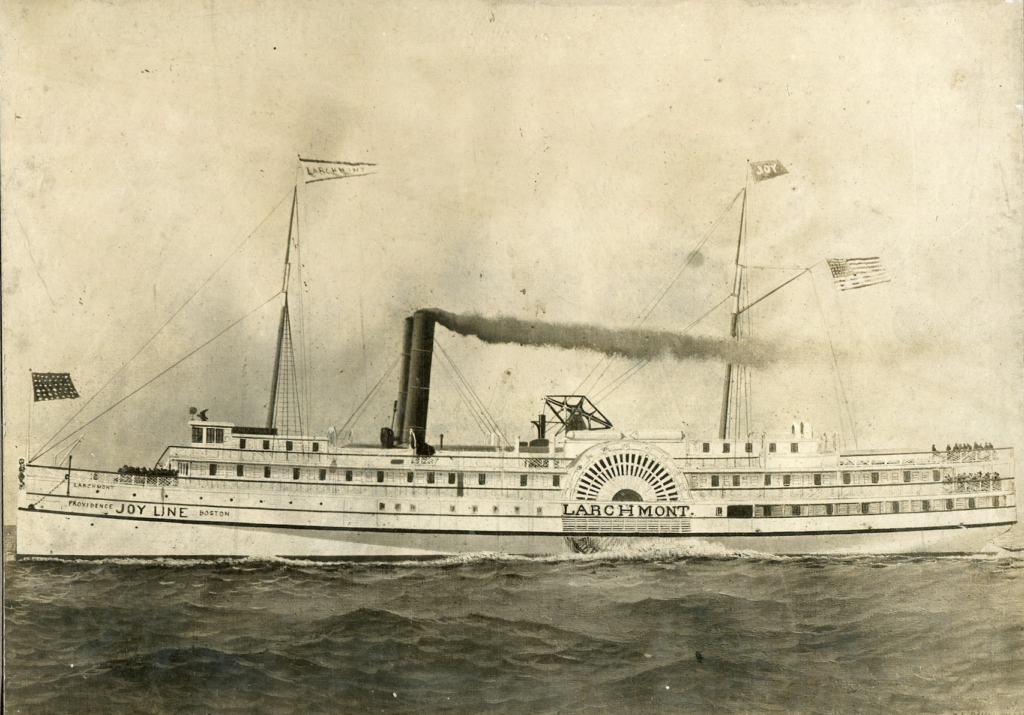

From a standpoint of loss of life there is no doubt that the very worst maritime disaster in Rhode Island waters occurred at almost the same spot where the METIS was lost in 1872, though this disaster took place thirty-five years later. As also in the case of the earlier side-wheeler, this disaster was caused by a collision between a schooner and the steamer. The steamer’s name was LARCHMONT and she belonged to the Joy Line. Her normal route was between Providence and New York City carrying passengers and some general freight. On the evening of February 11, 1907, the LARCHMONT was headed for New York. The night was clear, but the temperature was frigid, reportedly at just a few degrees above zero, with a furious northwest wind that sent the seas clear over the steamer causing her to labor heavily. Although there was no definite count of the number of passengers aboard, the estimates were as high as 150 or more in addition to the crew. In all, there were but seventeen survivors. An estimate of the time between collision and sinking indicated that just twelve minutes had elapsed. The culprit, or in this case the co-victim, was the schooner HARRY P. KNOWLTON of Eastport, Maine. She measured 317 tons opposed to the steamer’s 1,600 tons but she was reportedly carrying extra canvas to make up for lost time after having been trapped in ice in Long Island Sound before the collision. The KNOWLTON was on its way from South Amboy, New Jersey, to Boston with a cargo of soft coal. The two vessels crashed at about 10:45 p.m., about three miles southeast of the Watch Hill Lighthouse and almost due west of the northern point of Block Island. The schooner’s crew abandoned her when about a mile and a half off the beach at Quonochontaug and made it ashore in the schooner’s yawl. No one knew of the loss of the side-wheeler until the forenoon of February 12,, when bodies of the living and the frozen dead began to drift ashore on Block Island. It was widely believed that had the collision taken place in warmer months, the loss of life would not have been so severe.

Blame can be assigned to the captains of both the LARCHMONT and the KNOWLTON. Given that the night was clear, either vessel had the opportunity to steer clear of the other. There was an arrogance on the part of some steamer masters in not wanting to make way for the sailing vessels and this is most likely at least a major cause of the collision. The schooner was so heavily laden with coal that her maneuverability was, at the least, severely hampered, but she still could have tried to take some evasive action.

Without a doubt, the loss of the side-wheel steamer LARCHMONT, with only 17 survivors out of an estimated 150-200 aboard, represents the greatest loss of life in a maritime disaster in the history of Rhode Island (Providence Public Library Digital Collections).

Though countless other disasters have occurred in Rhode Island waters, and many of them have resulted in greater financial loss than the ten disasters summarized here, these were, by far, the most severe in terms of loss of life.

[Banner image: Passengers are seen on the Larchmont steamer from the Joy Line, and several flags wave from the vessel. It sank in collision with the Harry Knowlton on February 11, 1907 at about 11:30 p.m. off of Watch Hill, Block Island, with more than 150 lost and only 17 saved (Providence Public Library Digital Collections)]