In the vault at the South Kingstown Town Hall, tucked into the inside back cover of Town Meeting Records March 1798 to 1836 South Kingstown, there are several typewritten copies of a document titled “TOWN OF SOUTH KINGSTOWN CHARTER.” These are transcriptions of the handwritten records on pages 31-32 in South Kingstown Meeting Records 1723-1776, copied by South Kingstown town clerk Howard Perry on June 25, 1936. These copies of the original charter for South Kingstown detail why the town of Kingstown should be divided in “as near as could be into two parts” and defines the borders of South Kingstown in relation to Westerly and North Kingstown. It directs the town to elect a slate of town officers on the “first Tuesday of June Annually,” and to select jurymen for “each and every General Court of Tryal.” Finally, the Charter declares that the townspeople are “fully Authorized and Impowered to make by Laws for the better Regulation Governing and well ordering of their prudential affairs Provided that they be not contrary and Repugnant to the Laws of this Colony…”

This charter documents an important milestone in Rhode Island history: the founding of South Kingstown. Celebrating its 300th year this year and fondly referred to by southern Rhode Islanders as “SK,” the town was at one time was one of the five rotating capitals of the colony and (after May 4, 1776) the state of Rhode Island and still remains the seat of Washington County. (South Kingstown included what is now the town of Narragansett until 1911).

South Kingstown was also the first new municipality established after the turmoil of the seventeenth century. The petition to the General Assembly seeking a separate incorporation from the greater town of Kingstown established the precedent for the formation of every new town and city created in Rhode Island from a larger, preexisting polity.

This article, written in commemoration of that founding three hundred years ago, explores the events that led to the incorporation of South Kingstown in 1723. A second article that follows will address South Kingstown’s history from King Philip’s War to the early 1700s.

The First Settlers: The Narragansetts

The first settlements in what became South Kingstown in 1723 were home to the ancestors of the Narragansetts. Until recently, the lack of evidence of permanent villages led archaeologists to assume that the Eastern Woodlands peoples of southern New England such as the Narragansetts did not build them. It was hypothesized that native peoples lived in small winter-time hunting villages dispersed along internal waterways across the interior of Rhode Island and migrated in the spring to larger encampments along the coastline where they engaged in shell fishing and limited agriculture. In his innovative study of southern New England’s historical ecology, William Cronon’s description of Algonquian lifeways argued that in order to “take advantage of their land’s diversity, Indian villages had to be mobile.” In Cronon’s reconstruction, “villages tended to disperse” in the summer and “probably reassembled” in the winter. For Woodland societies in parts of New England far from abundant coastal resources available along Narragansett Bay and Rhode Island’s southern coastline, these characterizations are more apt and are also supported by historical accounts.[1]

But along the shores of southern Rhode Island, archaeologist Russell Handsman developed an alternative picture, a “homelands model” of land used by the Narragansetts:

By 3000 years ago a series of traditional homelands extended along the western side of Narragansett Bay, from Point Judith north past Wickford and Warwick to Providence and beyond…The core space of each homeland would have contained important settlement and meeting places, communal cemeteries and other sacred sites, and locations traditionally used for fishing and shellfish collecting. Dispersed beyond each core were dozens of wigwams, sometimes clustered in small hamlets, and locations where food (nut groves) and other resources (medicinal herbs, clays, and soapstone) were gathered. The ecological diversity and richness…of the…Bay and nearby wetlands, together with native ideas about resource conservation…helped to ensure that homelands were stable and permanent cultural landscapes.

Archaeologist Robert Hasenstab has also questioned whether the lack of evidence for villages is “an accurate reflection of Algonquian settlement,” or if “large settlements simply are not recognized because of ethnohistoric biases, poor preservation, or inadequate archaeological methods.” Critical of an over-reliance on shovel test pits and “CRM surveys as the source of settlement data,” Hasenstab argues that “more systematic, research oriented survey work” and “machine stripping [to] expose living floors” combined with soil coring, use of ground-penetrating radar, and magnetometers would be more likely to turn up village sites (author’s note: CRM stands for “cultural resource management”).[2]

This from the Rhode Island School of Design Museum: “For decades, this painting of a Native American sachem (chief or leader) was misidentified as a portrait of Niantic leader Ninigret II [of Rhode island]; recent scholarship indicates that the subject may be Robin Cassacinamon, an influential Pequot leader [of Connecticut]” (Rhode Island School of Design Museum)

Site RI 110 conforms to all of the…expectations used to describe a Native American village. The presence of dwellings and other structures at the site is supported by numerous post molds. Storage and other pits are ubiquitous across the entire site area. Evidence for processing activities and a wide range of artifact types [are]…consistent with a range of domestic activities carried out by both women and men. Pottery vessels…dispersed over the site area all result from processing and cooking. Additionally, stone and shell hoes, in addition to recovered maize fragments, demonstrate that horticulture was an established element in Late Woodland subsistence strategies for southern Rhode Island.

Other Native American sites in Rhode Island appear to have been established after European contact “in …settings that afforded access to trade centers and those rich in shellfish species…as wampum became economically important in the economic climate of competing native, Dutch, French, and English interests.” Dutch fur traders opened permanent trade connections with the Narragansetts following Adrian Block’s exploration of Rhode Island’s coast in 1614. And until he was killed by the Indians on Block Island in July 1636, the notorious curmudgeon and trader John Oldham had supplied the Narragansett Bay area with English goods.[3]

The First White Settlers

In 1637, only one year after Providence was settled, which concurred with the death of John Oldham, Roger Williams reports that “Canonicus Laid…out Ground for a trading house at Narragansett with his own hands” for Williams to make English goods available at Cocumscussoc, twenty miles closer to the Narragansett heartland than Providence. Williams, Jan Wilcox, and Richard Smith, Sr. established three temporary trading posts at Cocumscussoc, close by the present-day village of Wickford. Cocumscussoc remained an isolated English outpost in the Narragansett country for the next twenty years, as English settlement was limited before 1650 to Providence and Warwick on the mainland and Aquidneck Island (then called “Rhode Island”) in Narragansett Bay.[4]

Williams relocated from Providence to Cocumscussoc in 1647 and lived at or near the trading post until he left for his second voyage to England in 1651. The Narragansetts, according to Williams, often visited the trading post in groups, “ten or twenty in a Company to trade amongst the English,” and he estimated that “my trading house . . . yielded me £100 profit per annum.” This not insignificant sum of money in the mid-seventeenth century enabled Williams to “pay off the staggering debts he had accumulated moving from Massachusetts and then, later, to secure Rhode Island’s patent from Parliament. The year Williams left for England, Richard Smith, Sr. took over operation of the fortified trading post, with permission from the local sachems. Upon Smith’s death, his son Richard Smith, Jr., took over operation of “Smith’s Castle” at Cocumscussoc in 1666.[5]

In the 1660s, Jireh Bull of Newport built another trading post at Pettaquamscutt about nine miles south of Cocumscussoc, on the eastern slope of Tower Hill. Often confused with McSparran Hill, where a well-known wooden tower overlooks the Narrow River at the intersection of current Route 1 and Route 138, Tower Hill (also known as Pettaquamscutt) is two and a half miles south of the present-day wooden tower, between Torrey Road and Middlebridge. Bull settled on Tower Hill likely to be closer to Narragansett settlements such as RI 110, and likely the sachems who agreed to allow the settlement wanted a trading post located more conveniently for them than at Wickford. Bull’s trading post was also at that time within line of sight of Pettaquamscutt Rock (also known as the Treaty Rock) where in 1638 Roger Williams met with Narragansett sachems to confirm his purchase of Providence and to negotiate for the settlement of Aquidneck Island.[6]

While some accounts cite 1657 as the year Jireh Bull built his trading post, the best evidence points to his arrival in the 1660s. Land records indicate that in 1663, Bull purchased a twenty-acre house lot at Pettaquamscutt from one William Bundy and in March 1667 Bull’s “name first appears in legal documents as a resident of Pettaquamscutt.” By 1668 Bull purchased an additional 480 acres that adjoined his earlier purchase from the Pettaquamscutt Proprietors, making him at the time one of the largest landowners who actually settled in the area. By 1669 Pettaquamscutt had attracted at least six other early settlers who built homes in the vicinity. Bull’s trading post, also referred to as a garrison, was described by Connecticut colonist Wait Winthrop in 1675 as “a convenient larg stone house with a good ston wall yard before it which is a kind of small fortycation to it.” The trading post was the nucleus of the small village of Pettaquamscutt, the first English settlement in what later became the town of South Kingstown.[7]

Rhode Island’s seventeenth-century English settlements were all close to the coast and located near Native American “townes,” as Roger Williams referred to them. Consideration of larger and more permanent settlements of Narragansetts such as RI 110 in the vicinity of English villages like Pettaquamscutt made possible more extensive interactions between the English and the Narragansetts in the mid-seventeenth century than earlier interpretations might suggest.

Under the “homelands model,” and based on Roger Williams’s descriptions of the brisk business at Cocumscussoc in the 1640s, Narragansetts from their nearby settlements likely would have frequented Bull’s trading post at Pettaquamscutt on a regular basis. The Pequot Trail (later renamed the Post Road or the King’s Highway) was a well-traveled way between English and Narragansett settlements year-round.

Because the Narragansetts also practiced controlled burns of the forest twice yearly, the landscape along the road was mostly open space, and in places were probably park-like, favorable to grasses, berries, and attractive to deer and other game. The Narrow River, Pettaquamscutt’s eastern boundary, would have been visited regularly by vessels from Newport and Narragansett watercraft of various sizes.

Political and economic relationships between the English and the Narragansetts in the mid-seventeenth century in borderland settlements like Pettaquamscutt would have been conducted as exchanges between equals. This bucolic scene, however, if it ever existed, was short-lived. English land-fever took precedence over trade with the Narragansetts, a state of affairs that coincided with the demise of the region’s fur trade and turned this peaceful borderland area into a “contested frontier.”[8]

Major and Competing Land Acquisitions

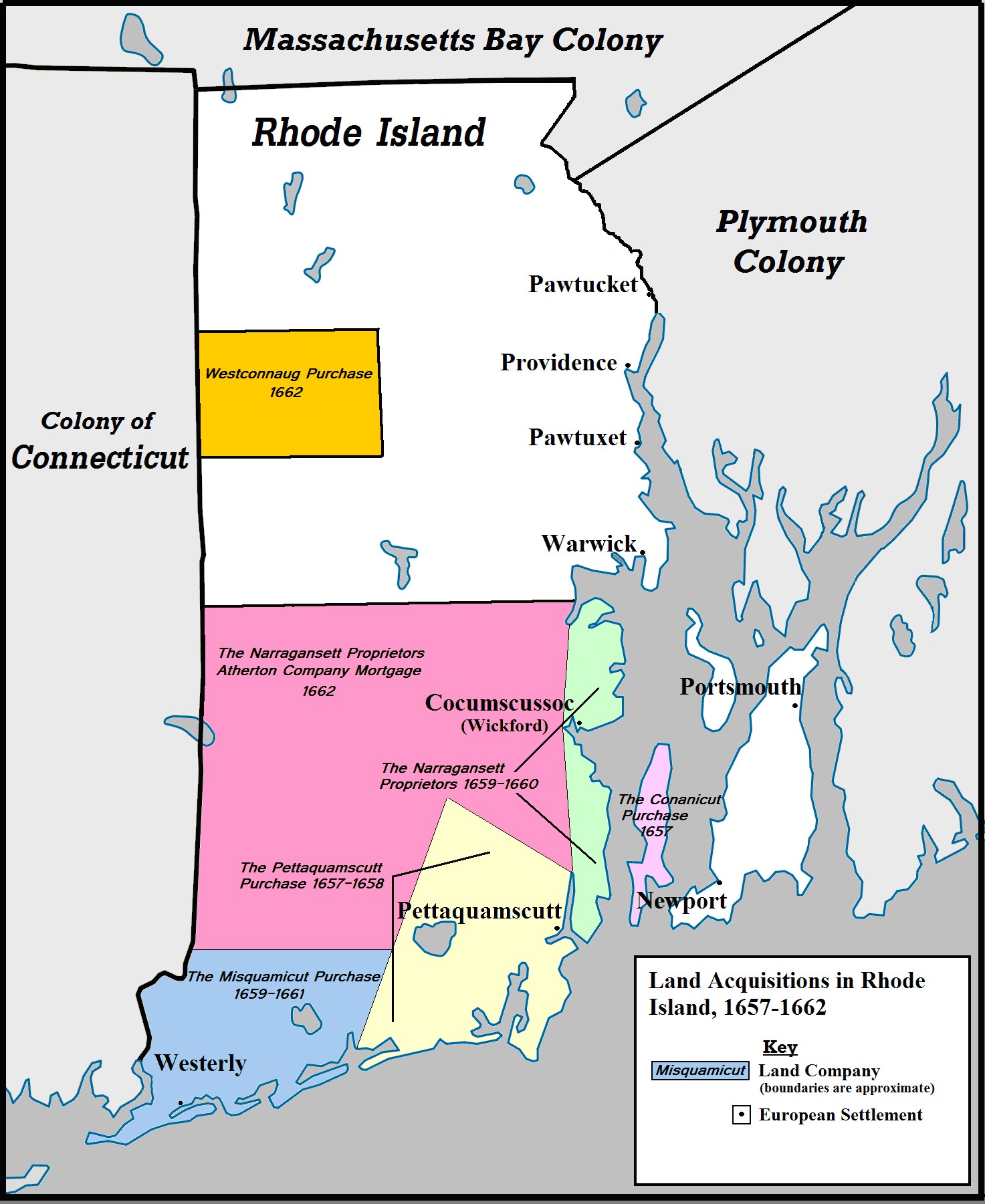

The larger area of South Kingstown can trace its beginnings of white settlement to a series of land acquisitions in the “Narragansett Country” in the late 1650s. Before Jireh Bull erected his trading post, two competing sets of English land speculators undertook a series of major land acquisitions in the area that would eventually become South Kingstown. This was the first significant transfer of Narragansett lands after the initial settlement phase from 1636 to 1643. The first, known as the Pettaquamscutt Purchase, was a series of purchases from three separate Narragansett sachems that, when put together, formed a twelve-square-mile parcel that would eventually encompass much of present-day South Kingstown and Narragansett south of Boston Neck (Figure 1). These purchases were conducted over the course of 1657 and 1658 by a group of men from Aquidneck Island with the approval of the Rhode Island General Assembly.

In 1659, another group of speculators, known as the Narragansett Proprietors, under the leadership of Captain Humphrey Atherton from Massachusetts, obtained control of Narragansett tribal lands using methods of dubious legality accompanied by the threat of war. Otherwise known as the Atherton Company, their claims (according to them) included all of the Narragansett lands south of Warwick. The foundation of their claims was based on an exorbitant and mostly invented fine that Atherton levied on the Narragansetts, which was secured by a mortgage on all the Narragansett lands. When the Narragansett refused to pay, the land subject to the mortgage underwent “foreclosure.”

The Narragansett Proprietors’ claims essentially papered over the outright theft of native lands. Though the Proprietors had also legitimately purchased Quidnesset to the north of Richard Smith’s trading post and the peninsula of Namcock (Boston Neck) to the south of Smith’s property, Rhode Island’s General Assembly condemned Atherton’s acquisitions through the mortgage as “fraud piled upon extortion” and refused to recognize any of their claims.[9]

Figure 1. Map of Land Acquisitions in Rhode Island, 1657-1662 (Mark K. Gardner; see endnotes for map credits)

The Proprietors’ foreclosure on the Narragansett’s mortgaged land was completed before Rhode Island received official jurisdiction over the territory south of Warwick in the Charter of 1663. Connecticut’s 1662 charter, argued the Puritans in Hartford, conflicted with those boundaries.

The Atherton proprietors took advantage of an arbitration clause in the Rhode Island charter that allowed local residents to decide which jurisdiction they preferred, Rhode Island or Connecticut. Since Rhode Island’s General Assembly refused to recognize any claims under the fraudulent mortgage, the Atherton proprietors simply voted their lands to be part of Connecticut. On July 10, 1663, the General Court of Connecticut established the town of “Wickforde” and appointed Richard Smith, Sr. and two others to serve as “select men at Mr. Smiths tradeing howse” with Richard Smith, Jr. to serve as “Constable for the said Town.”

Rhode Island condemned Connecticut’s claim as “legalized robbery” and in 1664 began “encroach[ing]” on Wickford despite Hartford’s claims and its appointment of officials. Meanwhile, to further complicate the jurisdiction of the Narragansett country, in 1658 Massachusetts renewed its claim to the area from Mystic River to Ashaway River—what is today Stonington and North Stonington in Connecticut—based on claims that had lain dormant since the Pequot War of 1637. Many of the settlers there, unhappy with Hartford’s refusal to grant them their own town government, allied themselves with Boston and agreed to form the town of Southerton. That same year Massachusetts also gifted “a large tract of land at Watch Hill to Harvard College” and to other Bostonians “almost the entire west half of the present town of Westerly,” though whether this section of what would later become Westerly was part of the jurisdiction of Southerton or overlapped with the Misquamicut Purchase is unclear.[10]

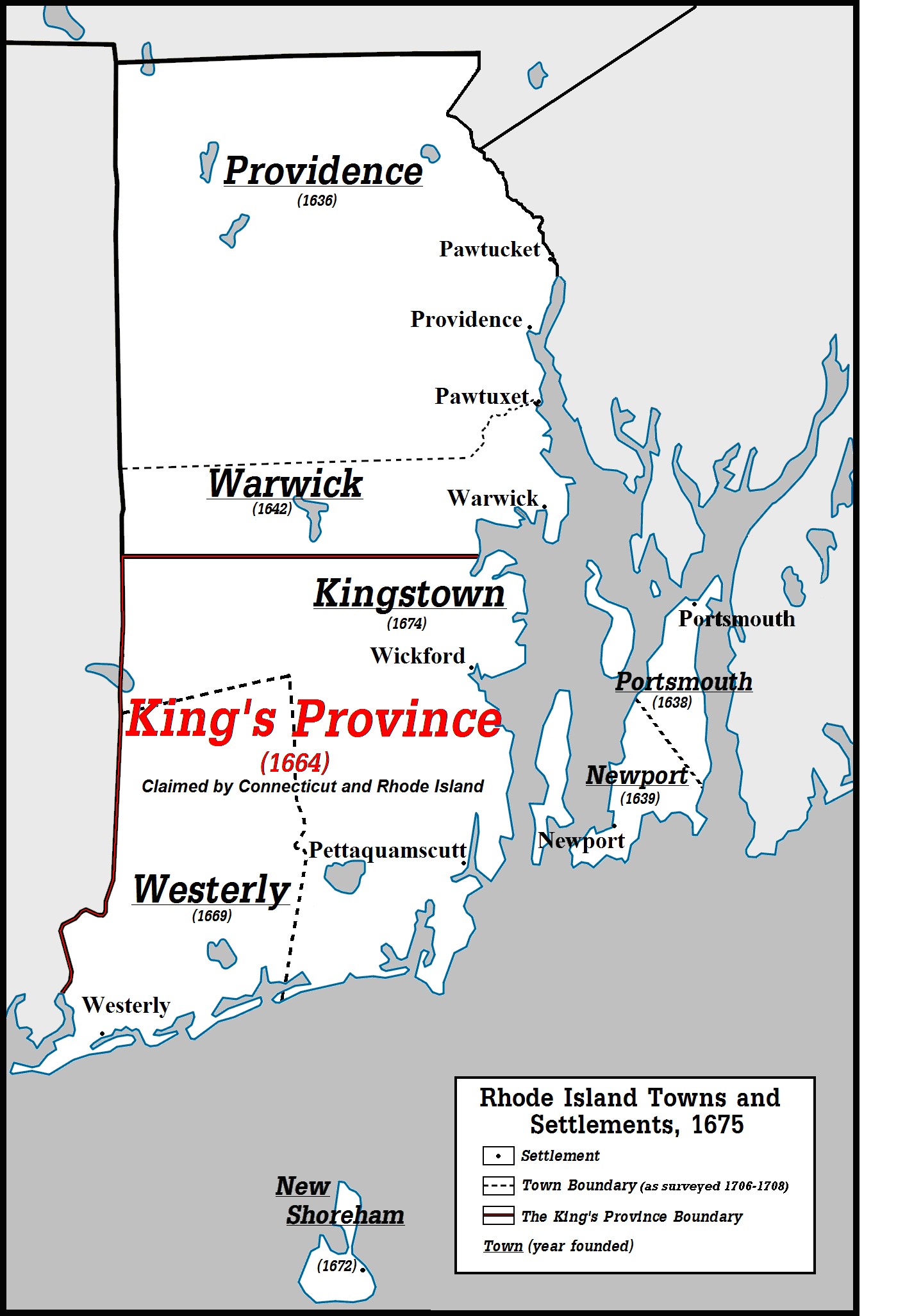

Thus began the long dispute over which colony had authority over the region. Connecticut, Rhode Island, and even Massachusetts all laid claim to some or all of the region. A royal commission was established in 1664 to get to the bottom of the conflicting land and jurisdictional claims. The commission quickly extinguished Massachusetts’s right to Rhode Island and Connecticut lands, based as it was on tenuous claims unsupported by a colonial charter. However, the commissioners could not reach consensus about the claims of Rhode Island and Connecticut over the Narragansett country. As a temporary solution, the commissioners designated the Narragansett country “The Kings Province” and placed jurisdiction with Rhode Island (see Figure 2). Connecticut and the Narragansett Proprietors immediately began a protracted series of appeals that froze the legal status of the region until the appeal process ran its course. As it turned out, that would take decades.[11]

Figure 2. Map of Rhode Island Towns and Settlements, 1675. (Mark K. Gardner; see endnotes for map credits)

Meanwhile, the colonial governments of each of Connecticut and Rhode Island appointed dueling sets of magistrates and other officials in an attempt to solidify its jurisdiction over the territory. In 1669 Rhode Island appointed four men to be “Conservators of the Peace in the King’s Province,” including “Mr. Jireh Bull…at Petaquomscut; and also…Mr. Richard Smith…about Narragansett and Acquidnessett.” In 1670, Connecticut appointed officers “with magisterial powers” in Wickford. A commission of men from both colonies that year tried to establish a mutually acceptable border, but disagreements arose over whether the “Narragansett River” set as Connecticut’s eastern border in the 1662 charter referred to Narragansett Bay or the Pawcatuck River some twenty miles west.

After negotiations broke down, officials from both sides were subjected to charges and arrests. Both colonies also tried to appoint the most prominent men living in this contested frontier to serve as the officials for their respective governments. Richard Smith, the commissioner of Connecticut’s General Court for the Narragansett Country from 1671 through 1674, was appointed a Conservator of the Peace by the Rhode Island General Assembly in 1669 and 1672, and an assistant to the governor in 1672 and 1674. Not to be outdone, the Connecticut General Court appointed Jireh Bull, Pettaquamscutt’s conservator for Rhode Island, a commissioner for Connecticut in 1673.[12]

With the jurisdictional dispute making land claims uncertain and with Puritans being hesitant to move to what could come under the control of heretic Rhode Island, few white settlers ventured to settle the Narragansett country. On October 28, 1674, the Rhode Island General Assembly incorporated the town of Kingstown in 1674, which today includes South Kingstown, North Kingstown, Narragansett, and Exeter. The new town rivaled Wickford only on paper, and had little immediate real impact. Connecticut did relocate its court for “setleing and management of gouerment in behalfe of the people seated in the Narragancet Country,” from Wickford to Stonington, perhaps in response to the creation of Kingstown.

Declaring a town around the tiny settlement at Pettaquamscutt did not inspire residents to send deputies to the General Assembly. Yet failure to send deputies to the General Assembly is not absolute proof that Pettaquamscutt lacked a local government. Westerly, for instance, was formally established as a Rhode Island town by the General Assembly in 1669 and established a local government, but over the next thirty years Westerly only rarely sent deputies to the Rhode Island legislature. While no records exist of a local government among the Pettaquamscutt settlers, this does not disprove the existence of one. If there had been a local government for Kingstown in Pettaquamscutt, its records would have been destroyed in 1675 when the settlement was burned in King Philip’s War.[13]

Likewise, despite Connecticut’s declaration that Wickford was a Connecticut “plantation,” no deputies were ever sent to Harford from Wickford, nor did Connecticut assess or collect taxes there. In the meantime, the Pettaquamscutt Purchasers simply sold off large tracts to whoever would buy them, such as Jireh Bull, while the intrigues of the Narragansett Proprietors to enjoin with Connecticut or gain support for their schemes from the Crown came to naught.

The Narragansett country remained a contested borderland; a libertarian paradise of cheap land, no taxes, and little government, despite all efforts to make it otherwise. This situation also afforded the tiny English outposts south of Warwick little in the way of security from the United Colonies of Connecticut, Plymouth, and Massachusetts, who had little regard for Rhode Island or Narragansett sovereignty. The Narragansett country also remained the home of thousands of Narragansetts, whose relationship with the United Colonies was about to take a turn from an uneasy peace to total war. Rhode Islanders did not join in the war against the Narragansett, but the small trading post settlement at Pettaquamscutt and the few other white settlers in South Kingstown would be caught in the middle.[14]

Endnotes

[1] From a conversation with curator and executive director Lorén Spears at the Tomaquag Indian Memorial Museum, Exeter Rhode Island, February 8, 2012; also see Alan Leveillee, Joseph Waller, Jr., and Donna Ingham, “Dispersed Villages in the Late Woodland Period in South-Coastal Rhode Island,” Archaeology of Eastern North America 34 (2006), 85; William Cronon, Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England (New York: Hill and Wang, 1993), 45, 47, 54. [2] Russell G. Handsman, A Homelands Model and Interior Sites A Phase II Archaeological Study of Rhode Island Site 2050, Phenix Avenue, Cranston, Rhode Island (Kingston: University of Rhode Island, Dept. of Sociology and Anthropology, Program in Public Archaeology, 1995), 4; Robert J. Hasenstab, “Fishing, Farming, and Finding the Village Sites Centering Late Woodland New England Algonquians,” in The Archaeological Northeast, edited by Mary Ann Levine, Kenneth E. Sassaman, and Michael S. Nassaney (Westport, CT: Bergin & Garvey, 1999), 140, 151-52. [3] Rhode Island Historical Preservation and Heritage Commission, Native American Archaeology in Rhode Island (Providence: Rhode Island Historical Preservation and Heritage Commission, 2002), 54; Leveillee et al., “Dispersed Villages in the Late Woodland Period in South-Coastal Rhode Island,” 78, 79, 86; Julie A Fisher, “Roger Williams and the Indian Business,” The New England Quarterly, Vol. 94, No. 3 (Sept. 3, 2021), 365. [4] Neil Dunay, Norma LaSalle, and R. Darrell McIntire, Smith’s Castle at Cocumscussoc: Four Centuries of Rhode Island History (East Greenwich: Meridian Printing Company Inc., 2003), 2, 5; Howard K. Stokes The Finances and Administration of Providence (Baltimore, MD: The John Hopkins Press, 1903), 11. For the establishment of Cocumscussoc by Canonicus see Fisher, “Roger Williams and the Indian Business,” 365, 367. [5] Fisher, “Roger Williams and the Indian Business,” 367; Dunay et al., Smith’s Castle at Cocumscussoc: Four Centuries of Rhode Island History, 2-3. [6] For general background of the early settlement at Pettaquamscutt see Walter Nebiker, Robert Owen Jones, and Charlene K. Roice, Historic and Architectural Resources of Narragansett, Rhode Island (Providence: Rhode Island Historical Preservation Commission, 1991), 7, Kathleen Bossy and A. Craig Anthony “The Pettaquamscutt Purchase,” in Kathleen Bossy and Mary Keane With Eighteen Contributing Authors, Lost South Kingstown, With a History of Ten of Its Early Villages (Kingston: The Pettaquamscutt Historical Society, 2004), 10; also see A Preliminary Report On the Excavations at the House of Jireh Bull On Tower Hill in Rhode Island / Issued at the General Court of the Society of Colonial Wars in the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, by Its Governor, Henry Clinton Dexter, Esquire, and the Council of the Society, December 31, 1917 (Providence: E.A. Johnson & Company, 1917), 7. For a history of Pettaquamscutt Rock, see William D. Metz, “Pettaquamscutt Rock Commemorated, May 11, 1958,” The Online Review of Rhode Island History (Jan. 7, 2016) at http://smallstatebighistory.com/pettaquamscutt-rock-commemorated-may-11-1958/. [7] For the construction of Jireh Bull’s garrison in the 1660s, see Colin Porter “Uncomfortable Consequences”: Colonial Collisions at the Jireh Bull House in Narragansett Country,” Rhode Island History Vol. 72, No 1 (Winter/Spring 2014), 8-15. For Wait Winthrop’s quote describing Bull’s garrison, see James Hammond Trumball (ed.), “The Public Records of the Colony of Connecticut, from 1665 to 1678; with the Journal of the Council of War, 1675 to 1678,” The Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/publicrecordsofc00unse, 338. [8] Leveillee et al., “Dispersed Villages in the Late Woodland Period in South-Coastal Rhode Island,” 75; Cronon, Changes in the Land, 49-51; Dunay et al., Smith’s Castle at Cocumscussoc, 11. Roger Williams, on page 29 of A Key Into The Language Of America, states in regard to Narragansett settlements: “In the Narigánset Countrey (which is the chief People in the Land) a man shall come to many townes, some bigger, some lesser, it may be a dozen in 20 miles travell.” Roger Williams, “A Key into the Language of America” (Bedford, MA: Applewood Books, 1997), accessed at Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_wOfpAPRxlVYC. In testimony about the lands between RI 110 and Pettaquamscutt, Wait Winthrop described the region as “ye bare Hills below the Plain which was then called Sugar Loaf Hills a great Way to ye Eastward the Country being mostly clear….” See William Davis Miller’, Ancient Paths to Pequot (privately printed, 1936), 8 (found at MSS 629 SG 12, Rhode Island Historical Society). Also see Colin Porter, “The Jireh Bull House at Pettaquamscutt: Archaeology of a Fortified House in Narragansett Country” (lecture, Aldrich House, Rhode Island Historical Society, Providence, RI, October 26, 2011). [9] Dunay et al., Smith’s Castle at Cocumscussoc, 13; Bossy et. al.,, Lost South Kingstown, 5-6; see also Elisha R. Potter, Jr., The Early History of Narragansett: With an Appendix of Original Documents, Many of Which Are Now For the First Time Published (Providence: Marshall, Brown and Company, 1835), 234-35; Sydney V. James The Colonial Metamorphosis of Rhode Island: A Study of Institutions in Change (Hanover: University Press of New England, 2000), 88-89. [10] The Public Records of the Colony of Connecticut, 1636-1776: May 1665 – November, 1677, vol. 1 (Hartford: Case, Lockwood & Brainard Company, 1850), 407; Clarence Winthrop Bowen, The Boundary Disputes of Connecticut (Boston: James R. Osgood and Company, 1882), 33-34. For Massachusetts land claims, see “The First Organized Church in New London County, An Historical Study By Hon. Richard A. Wheeler Read before the New London County Historical Society, at its Annual Meeting, Nov. 26th, 1877, Part 3” accessed August 12, 2005 – and thanks to MaryAlice Schwanke at CTGenWeb for repairing the link February 24, 2023 [http://www.ctgenweb.org/county/conewlondon/NLHistoricalChurch.htm]. [11] Wheeler, ibid.; James, Colonial Metamorphosis, 94. [12] See John Russell Bartlett (ed.), Records of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, in New England, Vol. 2 (Providence, RI: Knowles, Anthony & Co., 1856), 192, 256, 298. Originally these were commissions given to the President and Assistants of the colony “by [which] they shall keep the peace, and in case it be broke by threats, assaults, or affrayes, eyther before any of them or vpon lawfull complaint, he or they shall bind the parties by recognizance with two suffiecent sureties vnto the peace, and to appeare at that Court where such matters are to by tried…” For Smith and Bull’s appointments in Connecticut, see The Public Records of the Colony of Connecticut, 1636-1776, Vol. 2, 157, 196, 198. Smith’s allegiance appears most consistently to be pledged with Connecticut, going so far as to refuse election as an Assistant to the Governor of Rhode Island in 1673, though in a letter to John Winthrop in May 1672 he explained that he did accept an assistantship in Rhode Island that year in hopes “of furdung a comlyanc betwixt both Coloneys.” See Bartlett (ed.), Records of the Colony of Rhode Island, Vol. 2, 484; Dunay et al., Smith’s Castle at Cocumscussoc, 15. [13] Before 1696, Westerly sent deputies to the General Assembly only in 1681, 1682, and 1684. See James, Colonial Metamorphosis, 95-6; Bartlett (ed.), Records of the Colony of Rhode Island, Vol. 3, 98, 107, 150. [14] James, Colonial Metamorphosis, 93.Map Credits

Original Map Files for Figures 1 and 2

File:USA Rhode Island location map.svg, by NordNordWest

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:USA_Rhode_Island_location_map.svg>

These works are licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license, made available by the Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License: <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>.

In accordance with this license, please attribute any use of either or both of the following maps (Figure 1 and Figure 2) by the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license, by including its title and its author—Mark Kenneth Gardner.

Figure 1. Land Acquisitions in Rhode Island 1657-1662

Figure 1. Locations based on descriptions in Chapter 4, “Land Promotions and New Towns” in Sydney V. James, The Colonial Metamorphoses in Rhode Island: a Study of Institutions in Change, ed. Sheila L. Skemp and Bruce C. Daniels (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 2000), 82-100; Sydney V. James Colonial Rhode Island: A History (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. 1975), 27, and Edward T. Price, Dividing the Land: Early American Beginnings of Our Private Property Mosaic (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995), 60.

Boundary lines for land acquisitions are proximate.

Figure 2. Rhode Island Towns and Settlements, 1675

Figure 2. Sites of English settlements based on Douglas Edward Leach, Flintlock and Tomahawk: New England in King Philip’s War: frontispiece map, and Colin Porter, “Uncomfortable Consequences”: Colonial Collisions at the Jireh Bull House in Narragansett Country, Rhode Island History 72, no. 1 (Winter/Spring 2014), 2 (location of map).

Boundaries of towns based on James, Colonial Rhode Island, 84.