On the morning of January 20, 1887, Isabelle Bourne, who lived in the village of Greene in Coventry, told the police that her husband, Ansel, a clergyman, had been missing for three days. He had gone to Providence on January 17 to withdraw some money from his bank, but had not returned home. An account of Mrs. Bourne’s missing person report appeared in that afternoon’s Providence Evening Bulletin, but Bourne was not located until mid-March.

On Monday, March 14, Ansel Bourne said that at about 5:00 a.m., a noise that sounded like a gunshot woke him. His bed felt unfamiliar. He felt weak, as if he had been drugged. He went to the window, opened the curtain, and had no idea where he was or how he got there.

He opened his door, heard movement in the next room, and tapped on the door. Pinkston Earle opened the door and said, “Good morning, Mr. Brown.” Bourne replied, “My name isn’t Brown. Where am I?” Earle told Bourne that he was in Norristown, Pennsylvania, and that the date was March 14, 1887. Bourne was incredulous—the last thing he remembered was seeing Adams Express Co. wagons at the corner of Dorrance and Broad streets in Providence on January 17.

Two months of his life were missing.

Six weeks earlier, a man calling himself Alfred J. Brown had arrived in Norristown and rented a room in Earle’s house at 345 East Main Street. Brown opened a small store in the front part of the room, selling candy, stationery, and other small items. The Earle family noticed nothing unusual about Brown. He was quiet, punctual, and attended church on Sundays.

When Brown identified himself as Ansel Bourne, Earle feared that his tenant had lost his mind, and sent for Dr. Lewis Read. At Bourne’s request, Dr. Read sent a telegram to Bourne’s nephew Andrew Harris in Providence, who confirmed that Ansel Bourne was his uncle. Harris said he would travel to Norristown immediately. A story in the March 19 Philadelphia Inquirer describes Bourne’s emotional reunion with his nephew on March 18, and speculates that Bourne’s family many not have received any responses to their missing person newspaper advertisements because they described Bourne as having a long grey beard, but “Alfred Brown” had a cropped beard.[1]

What happened to Bourne? He had experienced a dissociative fugue, a rare condition that causes a person to lose access to his autobiographical memory and personal identity. A person in this state might adopt a new identity, or abruptly embark on a long journey. Incidents are usually triggered by trauma of some sort. There is little medical literature on dissociative fugue, and no standard medical treatment. It has been suggested that this is so because dissociative fugue challenges the conventional understanding of reality. There may be no contemporary research on the condition because modern psychology and psychiatry have adopted models of the mind that are incompatible with the idea that people can have a lapse not simply of memory, but a lapse of selfhood.[2]

A number of cases of dissociative fugue have been documented, but Ansel Bourne’s, which received widespread publicity, may be the best known. He probably was the inspiration for the name of the Jason Bourne character created by novelist Robert Ludlum.[3]

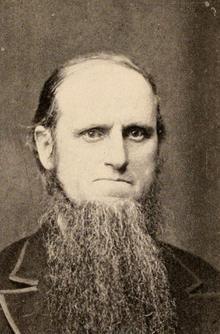

Ansel Bourne was born in New York City on July 6, 1826.[4] His father, Thomas Bourne, was a native of Sandwich, Massachusetts, and his mother, Betsey Greene, was from Warwick. His parents married in Pawtuxet on November 17, 1822.[5] When Ansel was seven years old, his parents separated, apparently because of his father’s drinking. When he was ten, his mother sent him to live with a family in Dartmouth, Massachusetts.[6] On September 4, 1839, Ansel’s older sister Lucy, then 16, married George J. Harris, 26, a carpenter and gunsmith.[7] Two years later Ansel and his mother went to live with George and Lucy in Olneyville, then part of Johnston, and Ansel was apprenticed to George to learn carpentry.[8]

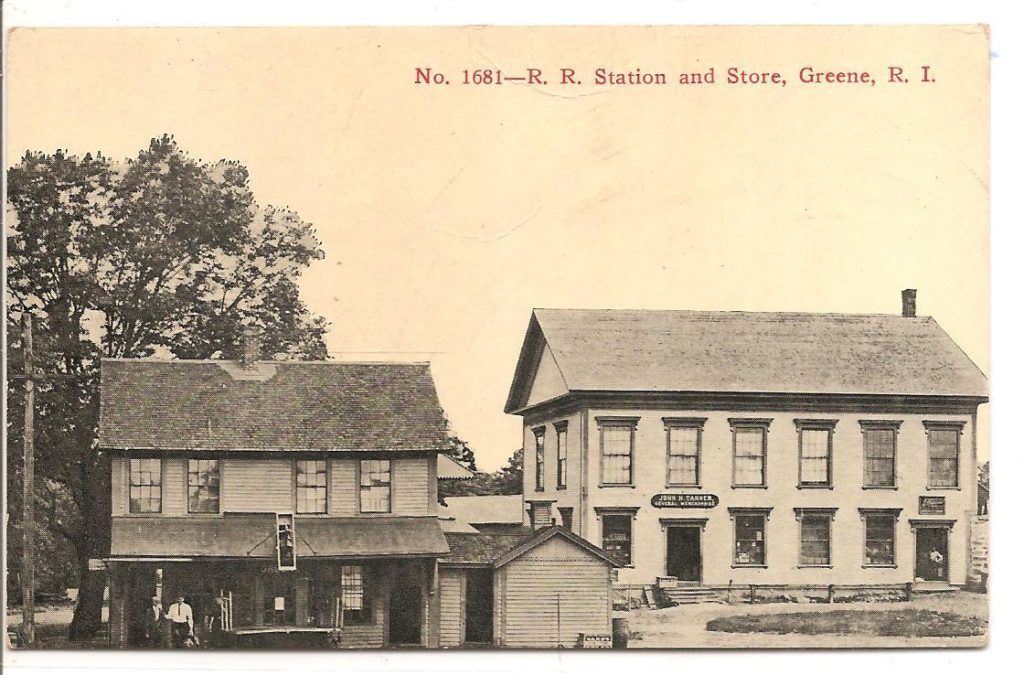

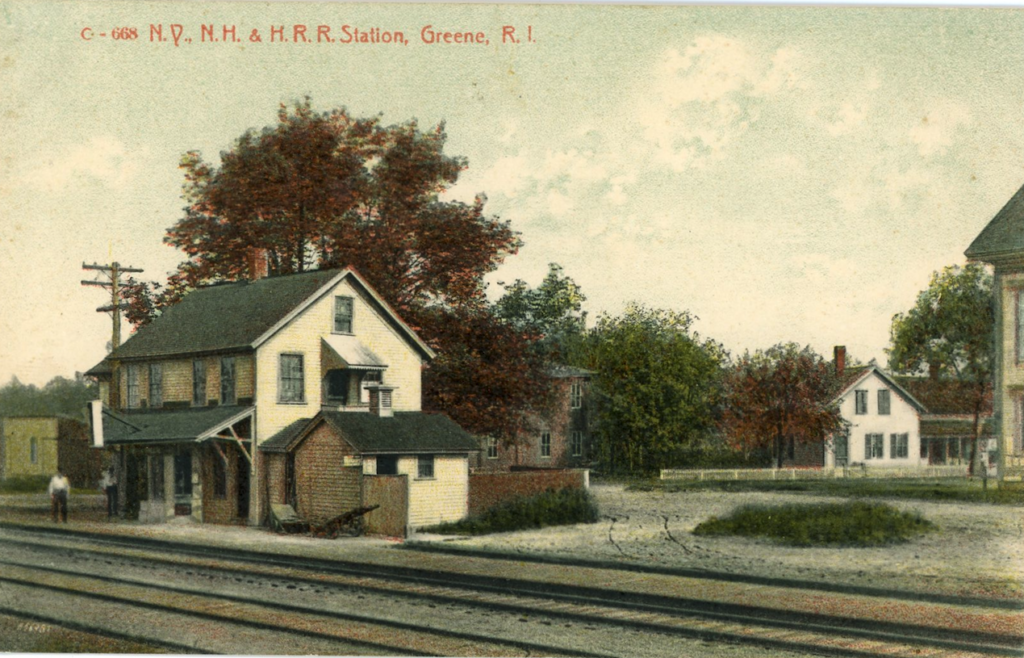

Greene railroad crossing, Greene Station (in Coventry, Rhode Island), N.Y., N.H. & H. RR (postcard, circa 1900) (Sanford Neuschatz Collection)

At the age of eighteen, Ansel set out on his own. On October 14, 1844, in South Kingstown, he married Sarah A. Woodmansee of Richmond.[9] They lived successively in Providence, Cranston, and Pawtuxet, but by 1850 they were living in Westerly.[10] Their house, which Ansel probably built, was on the east side of Beach Street near Wells Street.[11]

While he lived in Westerly, Ansel had a strange experience that revived his religious fervor. He believed that what happened to him was a miracle, but it may have been a precursor to the fugue he would experience in 1887.

Earlier in his life, Ansel had embraced religion, but by the 1850s, “his mind was under the dark and apparently unpenetrable [sic] cloud of unbelief.”[12] He hated churches and he hated ministers, including his next-door neighbor, Reverend John Taylor, the pastor of the Christian Chapel.[13]

In August of 1857, Ansel was building a house in South Kingstown for Rowland G. Hazard, who with his brother, Isaac P. Hazard, owned and operated the Peace Dale Manufacturing Company.[14] On August 6, Ansel felt ill and was brought home by a friend. He remained at home, and two weeks later began to experience intermittent periods of extreme head pain and weakness. For the next several weeks he was able to work only occasionally. On the morning of Wednesday, October 28, as he was walking from his home to the center of Westerly, the thought suddenly entered his mind that he should go to the meeting at the Christian Chapel. His next thought was, “I would rather be struck deaf and dumb forever, than to go there.” A few minutes later, he felt dizzy and sat down. Suddenly, to his horror, he could neither speak, nor hear, nor see. It seemed that God had taken him at his word.[15]

Someone found him and carried him home. Dr. William Thurston was summoned and judged Ansel to be unconscious; Ansel later said that although deaf and blind, he was aware of what was happening to him. The next afternoon, his sight returned, and he was able to communicate with his wife by writing on a slate. After spending a day reflecting on “the awful sinfulness of a life which had been brought by the hand of God to such circumstances,” he wrote on his slate that he wanted to see Reverend Taylor. When Taylor arrived, Ansel wrote on his slate an apology for his past behavior. The minister immediately forgave him and prayed with him.[16]

Ansel spent the next several days seeing, and asking forgiveness from, friends and neighbors for his real or imagined misdeeds. On Wednesday, November 11, he was carried to the Christian Chapel. He still could not hear or speak, so he wrote a message to the congregation on his slate that he was “determined to live for the honor of God,” and asked that it be read out loud. He returned to the church on Thursday, Friday, and Saturday. After the prayer he wrote on his slate was read out loud, he stood and “lifted his hands toward heaven.”[17] On Saturday, he became a member of the Christian Chapel.[18]

On Sunday, Ansel stood at the pulpit while his prayer was read. When he raised his hands, his hearing and speech suddenly were restored. As he fell to his knees and praised God, the entire congregation wept tears of joy.[19] Two weeks later, Ansel said, God appeared to him in a vision and said, “Settle up your worldly business, and go to work for me.”[20] Ansel became an evangelical preacher, although he continued to work as a carpenter. He preached at revivals and otherwise offered his services wherever he happened to be.[21]

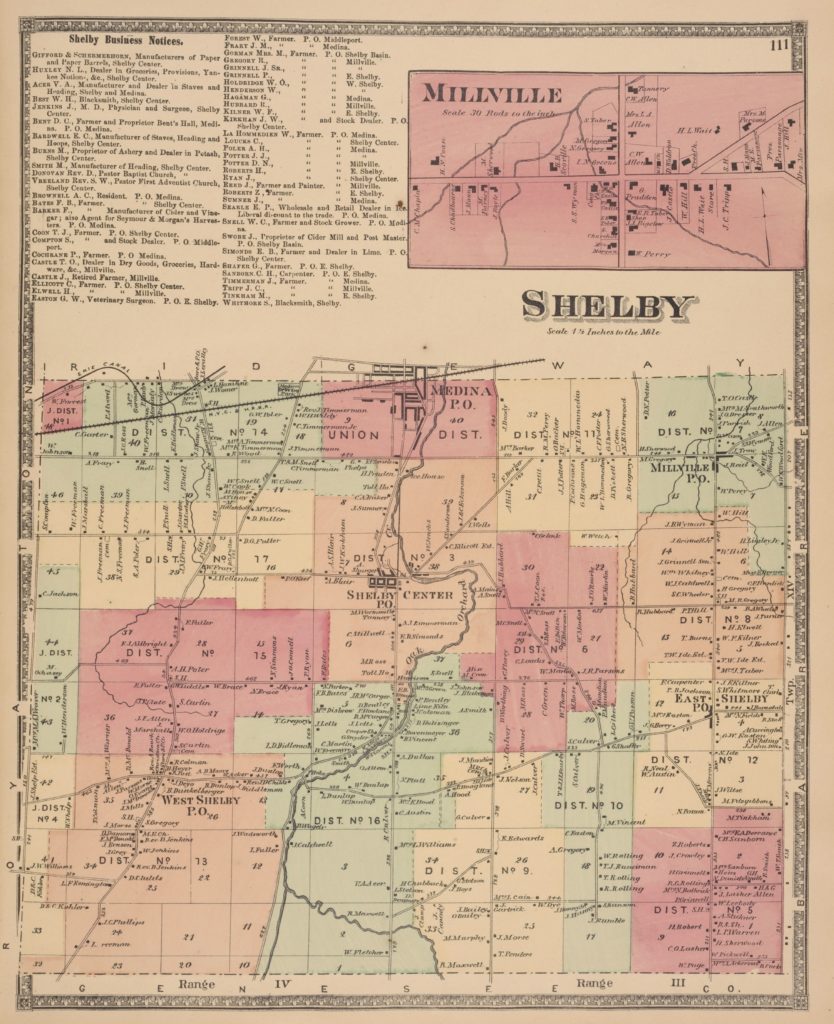

The Bourne family left Westerly in early 1860 and moved to Petersburg, Rensselaer County, in New York.[22] They relocated within New York at least twice— to Franklin in Delaware County, and to Tioga in Tioga County—before settling in Shelby, Orleans County, New York, by 1875.[23] Bourne served as pastor of the Christian Church of West Shelby for at least two years.[24]

Sarah Bourne died in West Shelby on July 8, 1881.[25] On September 8, 1882 in Johnston, Rhode Island, Ansel married Hannah Isabelle (Rice) Potter, a 41-year-old widow.[26] Bourne had probably returned to Rhode Island in 1881, after his wife died and all three of his children had married. It would not be unreasonable to assume that Bourne and Isabelle met at church. Isabelle asked him to give up his itinerant preaching.[27] He agreed, and they settled in Coventry, where he took up farming and apparently led an uneventful life until his trip to Providence on January 17, 1887.

Stories about Bourne’s episode of dissociative fugue appeared in dozens of newspapers throughout the country. Many treated his experience with derision or skepticism. According to the Brooklyn, New York, Daily Eagle, Andre Tridon, the author of Psychoanalysis: Its History, Theory, and Practice, opined that everyone has a Jekyll-and-Hyde-like double nature, and when we repress our animalistic tendencies, “the animal becomes enraged and breaks out of bonds.” As an example, he cited Ansel Bourne, “an overworked and overstudied preacher who became A. Brown, a fruit vendor.” Tridon said Bourne and others like him “were cured by self-analysis and by realizing the error of their ways.”[28]

Under the headline “More About Rev. Bourne,” a story in a Gilboa, New York, newspaper described Bourne’s Norristown experience and added, “This reminds us of our boyhood days when this individual came up to the Catskills to preach and deluded us into the belief that at one time in his Rhode Island home, where he was a very wicked man . . . he made the remark that he would rather be struck deaf, dumb and blind than to go [to church]. . . . Of course the children took it all in as true and the old hardened sinner considered it a miracle . . . if true, it is rather surprising that he should turn up in the general mercantile business in Pennsylvania after twenty-seven years of ministerial life and not know for six weeks that he was straying from the path of rectitude and virtue.”[29]

Physicians and psychologists had a much different reaction to Bourne’s experience— they found it fascinating. A number of doctors examined Bourne, the most prominent by far being Professor William James of Harvard, widely recognized as the father of American psychology. James theorized that under hypnosis, Bourne might once again become A. J. Brown and could be questioned about the circumstances that led to his personality fracture.

Bourne spent several days in the spring and summer of 1890 in Cambridge with James and a colleague. Each day, he was hypnotized and described in detail his activities between January 17 and March 14, 1887. He said he had traveled by train from Pawtucket to New York and then to Newark, New Jersey, and on to Philadelphia. The details he provided about where he stayed were later verified.

As Alfred J. Brown, Bourne gave James his correct date of birth, but said he was born in Newton, New Hampshire. He said he had endured a great deal of trouble in his life, most recently his wife’s death. But he was unable to clearly describe what happened before he found himself in a horse car traveling from Providence to Pawtucket on January 17, 1887. Everything was confused, he said; he had wanted to get away somewhere and rest. On May 31, James hypnotized Bourne and then said, “What’s your name? It’s Bourne, isn’t it ?” “No, it’s Brown.” He was awakened and re-hypnotized by James’s colleague, who asked the same question and received the same answer.[30] Brown said he had heard of Bourne but had never met him. Remarkably, he did not recognize a photograph of Sarah Bourne.

James observed that “the Brown personality seems to be nothing but a rather shrunken, dejected and amnesic extract of Mr. Bourne himself. He gives no motive for the wandering except that there was ‘trouble back there’ and he ‘wanted rest.’ During the trance he looks old, the corners of his mouth are drawn down, his voice is slow and weak, and he sits screening his eyes and trying vainly to remember what lay before and after the two months of the Brown experience. ‘I’m all hedged in,’ he says. ‘I can’t get out at either end. I don’t know what set me down in that Pawtucket horse car, and I don’t know how I ever left that store, or what became of it.’”

James had hoped to merge the two personalities to make the memories continuous but was unable to do so. “Mr. Bourne’s skull today still covers two distinct personal selves,” James said.[31]

Shelby, N.Y. Business Notices, Atlas of Niagara and Orleans Counties, N.Y. published by D.G. Beers & Co., 1875 (New York Public Library Digital Collections). The locations of Ansel Bourne’s home and the Christian Church of West Shelby are shown on this map at the northwest corner of the crossroads at West Shelby P.O.

Isabelle Bourne died in Cranston on April 14, 1910, and was buried next to her second husband John W. Potter.[32] Immediately after her death, Ansel moved to Buffalo, New York, to live with his son Alonzo and Alonzo’s family.[33] He died in Buffalo on September 6, 1915, and was buried at Mount Pleasant Cemetery in West Shelby, New York, next to Sarah.[34] The obituary in The Medina Tribune did not mention the events for which he was so famous. It said simply that “Ansel Bourne, an old and respected resident of West Shelby, passed away Monday evening at the home of his son Alonzo Bourne of Buffalo.”[35]

[Banner image: Greene railroad crossing, Greene Station (in Coventry, Rhode Island), N.Y., N.H. & H. RR (postcard, circa 1900) (Sanford Neuschatz Collection)]

Notes

[1] The Philadelphia Inquirer, 19 March 1887, 1; Ann L. Smith, “Ansel Bourne—The Later Years,” Westerly’s Witness (Westerly, R.I. Historical Society), January-February 2014, 4. [2] Rachel Aviv, “The Edge of Identity,” The New Yorker, April 2, 2018. [3] Lee Ferran, “Bourne’s Real Life Identity,” abcnews.go.com, August 3, 2007, at https://abcnews.go.com/Entertainment/story?id=3445059&page=1. [4] Wonderful Works of God: A Narrative of the Wonderful Facts in the Case of Ansel Bourne, of Westerly, Rhode Island . . . Written Under His Direction [hereafter Wonderful Works of God] (Irvington, N.J., Moses Cummings, 1858), 5. [5] James N. Arnold, Vital Record of Rhode Island, 1636-1850, 21 vols. (Providence, R.I.: Narragansett Historical Publishing Company, 1891-1912), 17:113. [6] Wonderful Works of God, 5 [7] Arnold, Vital Record, 2:21. [8] Wonderful Works of God, 5. [9] “Rhode Island Marriages, 1724-1916,” FamilySearch.org. [10] 1850 U.S. Census, Westerly, Washington Co., R.I., roll 847, p. 408A. [11] Albert P. Pendleton, “The Watch Hill Road,” Four Papers Delivered Before the Westerly Historical Society (Westerly, R.I.: The Utter Company, 1916), 28-29; Atlas of the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations (Philadelphia: D.G. Beers & Co., 1870), Westerly plate; Atlas of Southern Rhode Island (Philadelphia: Everts & Richards, 1895), Westerly plate. [12] Wonderful Works of God, 11. [13] The Christian Chapel Society, organized in 1843, merged with the First Christian Church in 1876 to become the Broad Street Christian Church. Arnold, Vital Record, 11:309. In 1857, the Christian Chapel occupied the building at 1 Granite Street that is now the Granite Theater, although the appearance of the building has been altered significantly. Granite Theater website, at https://www.granitetheatre.com/about-us/our-history (accessed April 16, 2018). The congregation probably was affiliated with the Protestant denomination now known as the “Christian Church (Disciples of Christ).” [14] Caroline E. Robinson, The Hazard Family of Rhode Island, 1635-1894 (Boston, MA: Merrymount Press, 1895), 122-123. The Hazards built a number of residences in Peace Dale for their employees. The house Bourne built could have been one of the earliest of those. U.S. Department of Interior, National Park Service, National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form for Peace Dale Historic District dated August 1986, R.I. Historical Preservation and Heritage Commission. [15] Wonderful Works of God, 14-15. [16] ibid., 19-21. [17] Ibid., 23-25. [18] Arnold, Vital Record, 11:311. Bourne’s wife, Sarah, became a member on December 6, 1857. [19] Wonderful Works of God, 27-28; Ann L. Smith, “The Strange (and Miraculous?) Case of Ansel Bourne,” Westerly’s Witness (Westerly Historical Society), November-December 2013, 3. [20] Wonderful Works of God, 33. [21] Alice B. Bodington, “Psychology: A Study in Morbid Psychology, with Some Reflections,” The American Naturalist (Philadelphia, PA: The Edwards & Docker Co.), June 1896, 30:518. [22] Ansel and Sarah were “discharged” from membership in the Christian Chapel Society on March 16, 1860. Arnold, Vital Record, 11:311. They were enumerated in Petersburg, New York, in the June 1860 U.S. census, where Ansel’s occupation was listed as “Christian minister.” 1860 U.S. Census, Petersburg, Rensselaer Co., New York, roll 848, p. 479. [23] 1865 New York State Census, Franklin, Delaware County, district 2, 7; 1870 U.S. Census, Tioga, Tioga County, New York, roll 1103, p. 365A; 1875 New York State Census, Shelby, Orleans County, sheet 38, line 32. [24] Isaac S. Signor, ed., Landmarks of Orleans County New York (Syracuse, N.Y.: D. Mason & Co., 1894), 554-555; The Medina Tribune (Medina, N.Y.), April 4, 1872 (“It is expected that Rev. Ansel Bourne will remain with the Christian Church of [West Shelby] another year.”). [25] FindAGrave.com memorial # 111399322. [26] “Rhode Island Marriages, 1724-1916,” FamilySearch.org. Isabelle had been married in succession to two Potter brothers. Her first husband, Joseph B. Potter, died only two months after their marriage in 1861. “Rhode Island Marriages, 1724-1916,” FamilySearch.org; Providence Evening Press, 11 June 1861, 3. Five years later, she married Joseph’s younger brother John, who died in 1879 at the age of 36. “Rhode Island Marriage Index,” Ancestry.com; FindAGrave.com memorial # 111667880. [27] Bodington, “Psychology,” 518; 1885 Rhode Island State Census, Coventry, Kent County, vol. 14, household 20. [28] The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Brooklyn, N.Y.), April 11, 1920, 6. [29] The Gilboa Monitor (Gilboa, N.Y.), April 14, 1887. [30] Bodington, “Psychology,” 30:514-515. [31] William James, The Principles of Psychology, 2 vols., reprint (New York: Dover Publications, 1950), 1:390-393. James made a point of observing that none of the physicians who had examined Bourne doubted his ingrained honesty, and none of his personal acquaintances were skeptical about his story. [32] “Rhode Island Deaths and Burials, 1802-1950,” FamilySearch.org; FindAGrave.com memorial # 125810902. [33] 1910 U.S. Census, Buffalo, Ward 15, Erie Co., N.Y., roll 945, p. 9B. [34] FindAGrave.com memorial # 43499985. [35] The Medina Tribune (Medina, N.Y.), Sept. 9, 1915.