Many Rhode Islanders are familiar with the sinking of the U-853 off Block Island in May 1945 at the very end of World War II. German U-boats had been prowling Rhode Island waters for a long time, in fact even before the United States entered World War I. This story is about one of the most audacious U-boat encounters, that of the U-53 and its visit to Newport in the fall of 1916.

As World War I raged on land in Europe, numerous accounts of this U-boat’s visit to Rhode Island appeared in publications on both sides of the Atlantic. In October 1916, a German submarine commander scored an intelligence coup resulting from the Newport visit that directly led to the sinking of five (possibly six) vessels off the Nantucket coast. This situation created hard feelings between the British and American governments, but it also provided the U.S. Navy with a first-hand look at the advanced level of undersea technology facing the U.S. if it were to enter the war. Yet the story has been all but forgotten by the general public today.

A highly detailed report of the incident is contained in a 1920 U.S. Navy publication titled German Submarine Activities on the Atlantic Coast of the United States and Canada. More recently, Robert K. Massie’s excellent 2003 account of the British Navy in World War, Castles of Steel, succinctly summarizes the event. Here is the full story of how a daring and clever U-boat commander used a visit to Newport to add to his bag of enemy vessels, sinking five (possibly six) ships in a single day in international waters off the coast of Nantucket.

The “war to end all wars” had been raging for two years. The outcome was still in doubt and the casualties on all sides were continuing to mount at a horrifying rate. America was supplying the Allies (on a cash and carry basis) with needed materials, and was also selling some supplies to the Germans. However, British and other foreign flagged ships were suffering increasing losses as they sought to run the German blockade on the European side of the Atlantic. The U.S. had managed to remain officially neutral even after the loss of American lives from U-boat attacks, including those aboard the torpedoed Cunard liner Lusitania in 1915. After the sinking of the Lusitania, Kaiser Wilhelm ordered the German navy to observe International Prize Regulations covering attacks on merchant vessels. German submariners were told to especially avoid attacking American flagged ships, as the Kaiser wanted America to continue to stay out of the war.

By 1916, the Germans were well ahead of the Allies in submarine technology. They had excellent torpedoes for both surface and undersea launches. In addition to attack submarines, they were building a fleet of large, long-range merchant cargo submarines capable of round-trips across the Atlantic without refueling. These 1,500 ton monsters were nominally under control of the German North Lloyd Shipping Company. However, only two of the planned seven were actually used as unarmed merchant vessels. By February 1917, the remainder had been taken over by the German navy and were used as offensive weapons through the end of the war.

In June 1916, one of the merchant cargo submarines, the Deutschland (later to become U-155) successfully ran the British blockade, crossed the Atlantic and sailed into Baltimore harbor. She returned to her homeport in August with about one million dollars’ worth of rubber and precious metals in her hold. The same submarine made a second successful trip to the U.S. in November, visiting New London, Connecticut. Although the British protested the use of submarines as merchant vessels, the U.S. accepted the concept. A second cargo sub, Bremen, disappeared on her maiden voyage and was believed sunk in September of 1916 (although the actual cause of the loss remains a mystery to this day).

The combat submarine U-53, on her first war patrol after commissioning, had been sent into the Atlantic to protect the unarmed Bremen from British warships. With the apparent loss of the Bremen, U-53 was ideally positioned in the midst of the East Coast shipping lanes with a host of enemy merchant vessels as potential targets.

U-53 was under the command of Kapitanleutnant (Klt) Hans Rose (pronounced “Roos-uh”}, who had already earned a reputation as a clever and highly respected commander. His superiors had told him that if the Bremen failed to make port he was free to go after enemy merchant shipping. German submarines, although very sophisticated for their time, nevertheless, were relatively small and had a range of only about 5,000 miles. To make the cross-ocean voyage and return, Rose reconfigured his ballast and trim tanks to hold fuel and water respectively. He carried extra food and two extra torpedoes to supplement the normal load of seven. The added fuel gave the sub a range of between 8,000 and 11,000 miles (equivalent to a World War II U.S. Navy submarine). U-53 endured a rough crossing and upon reaching the U.S. coast, on September 28, picked up an American radio signal conveying information that the Bremen had failed to make port and was presumed to have been lost. With this news, Rose changed his plans.

In spite of the difficult crossing, during which the U-53 sustained some damage that could be repaired, Rose decided on a bold plan that would bring the war close to the shores of neutral America. He started to implement the first phase of his plan around 2:00 p.m. on Saturday, October 7, ordering U-53, travelling on the surface, to head towards Newport.

At about the same time, U.S. Navy Lieutenant G.C. Fulker and his crew were patrolling the waters off Rhode Island in the coastal submarine D-2, about three miles east of Point Judith when they received a radio message of a possible submarine sighting. After a brief search, Fulker spotted the German U-53 on the surface heading towards Newport. At first, the German sub shied away from the American boat which had submerged after receiving the radio message. The D-2 resurfaced, the American flag was run up, and it sailed parallel to U-53. As the two submarines reached the Brenton Reef lightship outside Narragansett Bay, Klt. Rose hailed Lt. Fulker by megaphone and asked permission to enter Newport harbor. Fulker contacted his superiors by radio and the request was approved. Rose then called back through his megaphone, “I salute our American comrades and follow in your wake.” D-2 escorted U-53 through the bay’s East Passage into the harbor, anchoring off Goat Island within sight of the Naval War College and the Newport Naval Station. Crewmen aboard the destroyers moored in the main channel rushed to see the sleek German submarine. Needless to say, the presence of this impressive German warship elicited considerable surprise and excitement among both the military authorities and the civilian population.

U-53 had been directed to drop anchor near the cruiser USS Birmingham, flagship of Rear Admiral Albert Gleaves, commanding the Newport-based Atlantic Destroyer Flotilla. Rose brought his crew on deck in full dress uniforms, replete with medals, to impress his surprised hosts. Admiral Austin M. Knight, commander of the Newport Naval Base and president of the Naval War College, dispatched a U.S. Navy officer in small boat to ask Rose about his intentions. Rose asked the officer to be taken ashore to meet Admiral Knight. Once there, Knight conducted a formal and somewhat stiff interview with Rose and informed him that he could remain in the neutral port only a few hours, or risk being interned (messages were already flying back and forth between Newport and Washington seeking guidance). Rose also visited Admiral Gleaves aboard his flagship. Gleaves, more hospitable than Knight, apologized that he could not offer Rose a drink, since the abstemious Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels had recently forbidden alcohol use aboard U.S. Navy ships.

U-53 visiting Newport Harbor, with Admiral Gleaves’s gig alongside. Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly’s October 19, 1916 edition ran a story on U-53’s visit to Newport (Naval War College Museum)

The German captain indicated that he needed no assistance or supplies and intended to leave the harbor before 6:00 p.m., well within the time frame to prevent his men from being interned. Rose was very proud of his boat and invited Gleaves and other high-ranking Navy officials and their wives aboard U-53 for drinks. He also spoke with members of the press in the three hours he was in the harbor. One enterprising reporter came alongside the submarine in a small motorboat. Asking Rose if he had come to be interned, the German captain replied that he had not, but would appreciate if the reporter would mail a letter to Count von Bernsdorf, the German ambassador in Washington. Rose handed over a thin envelope and the reporter sailed off to shore.

American officers were thrilled to come aboard U-53 and go below to get a first-hand look at the highly advanced German submarine technology. At least one was an intelligence officer who took careful notes of everything he saw. That detailed intelligence report, still on file in the archives of the Naval War College, provided a thorough review of the submarine’s capabilities and equipment. Meanwhile, U-53’s crewmen lounged on the decks, waving to and chatting with the press and local residents who came along side. The Germans even played music on their phonograph to entertain their curious audience.

The crew of U-53, which visited Newport in 1916. Rose is the third officer in from the right (Wikipedia)

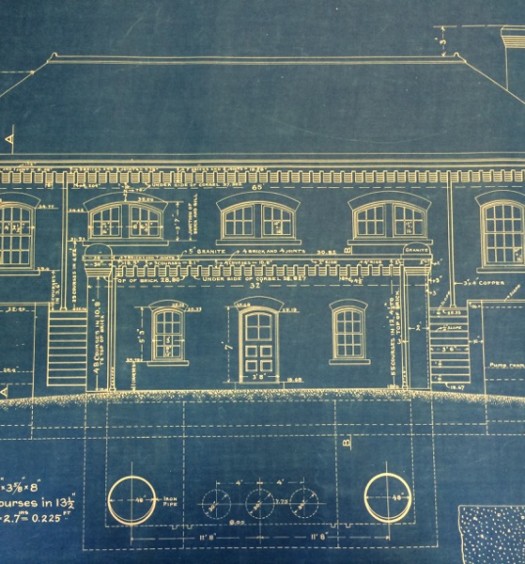

At 212 feet in length, U-53 was close in size to American submarines of the period. But with the realignment of ballast tanks to carry extra fuel, its range had been increased to far more than that of any existing American subs. U-53 was powered by two 1,200-horsepower, six-cylinder diesel engines. It had a maximum surface speed of 17 knots and could travel submerged under battery power at 9 to 11 knots. At an economical speed, it had a then astounding range of 9,400 nautical miles, more than enough for a round-trip across the Atlantic.

The boat was equipped with four 18-inch torpedo tubes, two fore and two aft (with four torpedoes loaded in the tubes and six spares (although for this trip, only four spare torpedoes were visible to those allowed to visit inside the submarine). Any remaining space had been made available for extra provisions. For surface encounters, the boat was armed with a pair of 8.8cm (3.5”) deck guns. An interesting novelty was a third periscope mounted forward of the engine room and used by the chief engineer. Crew consisted of the captain, three officers (exec/navigator, engineer and electrical/radio), and 33 enlisted men. The U.S. Navy intelligence report, echoed by the comments of those allowed aboard, described the boat as well-laid out, extremely neat and clean with “no trace of foul air anywhere.” Its radio equipment, according to Klt. Rose, could receive messages from a distance of 2,000 miles.

Meanwhile, questions and instructions were being relayed back and forth between Newport and Washington about the surprise appearance of U-53. The niceties ended quickly when Admirals Gleaves and Knight were ordered by their Washington superiors to direct Rose to leave the harbor and U.S. territorial waters immediately, which Rose did not mind since he had already accomplished his mission. While ashore at the War College, Rose had obtained a copy of a New York newspaper that carried shipping news notices. He was aware that the neutral Americans had no censorship issues preventing the publishing of such information, which was of great interest to the German submariners.

According to Lawrence Perry in his 1918 book, Our Navy in the War, getting the shipping news notices had been the real reason for Rose’s visit all along. Another unsubstantiated account, printed in the Newport Mercury a week after the incident, suggested that in the rush of visitors allowed on the boat, one man mysteriously offered 25 dollars to a boatman to take him immediately and quietly to shore. In the wake of Rose’s visit, hints of spies and intrigue abounded.

About 5:30 in the afternoon, U-53 set sail with its crew on deck waving and saluting the Navy ships at anchor. A large sailing yacht came up about 30 feet away and briefly paralleled the German boat’s course. Rose tossed out a life ring in final salute, called “good luck” and, when his boat had passed the Brenton Reef lightship into Rhode Island Sound, issued the order to dive. Newport had seen the last of its unexpected visitor. Overnight, Rose maneuvered outside the U.S. territorial waters and came to rest off Nantucket.

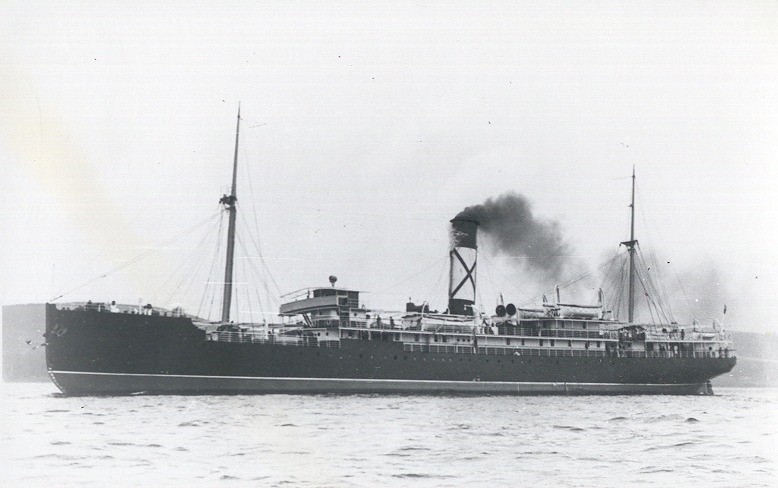

The next day, not far from the Nantucket Shoals lightship and in the principal shipping lanes to New York City, Klt. Rose and his crew stopped and sank five merchant ships: the 3,449 ton British S.S. Stephano (with American passengers aboard), the 4,321 ton British SS. Strathmore, and the 3,847 ton British S.S. West Point, followed by the 4,850 ton Dutch steamer S.S. Blommersdijk and the 4,224 ton Norwegian S.S. Christian Knudson. Rose also claimed to have sunk another British ship, the S.S. Kingston, inbound to New York, but this claim is doubtful since the Kingston was later accounted for and a ship with a similar name was not lost until 1918. Moreover, no crew was ever found from a sixth ship. According to survivors, Rose first fired torpedoes and then, using deck guns mounted on the submarine, fired twenty-five shells at the Stephano before the liner sank.

The S.S. Stephano, a British liner that had American passengers on board, sunk by U-53 of Nantucket after its visit to Newport (Wikipedia)

All passengers and crew were allowed to board lifeboats before the ships were sent to the bottom. In each case, the Germans observed existing International Prize Regulations by first determining whether the ships were carrying contraband. An American-Hawaiian line steamer, S.S. Kansan, had been stopped but was allowed to continue after Rose examined her papers.

When U-53 fired her first shots at Stephano, an SOS was radioed to shore by the targeted ship. In response, in Newport Admiral Gleaves immediately dispatched a squadron of sixteen destroyers to the scene. They were mustered so quickly that some sailed without all their crews aboard. The Americans arrived in time to rescue all crew and passengers from the stricken ships and to witness Rose continuing to pick off his remaining targets. At one point, the German skipper almost collided with one U.S. destroyer and then asked another to back away so he could get a clear shot at one of his victims. The U.S. Navy captain obliged and Rose sank the target with his last remaining torpedo.

After downing the fifth ship, Rose and his crew set sail for Germany, having accomplished everything they had set out to do. The Germans added to the confusion by changing the hull number of their U-boat, creating a myth that U-53 was not operating alone. According the U.S. Navy, the boat returned to Germany carrying hull number U-61.

U-53 evaded a number of British warships on its journey home. The Royal Navy dispatched a squadron of ships from its Halifax, Nova Scotia, base as soon as the word of the first sinking was received, but they arrived long after the Germans had departed. U-53’s successful patrol covered more than 7,500 miles without refueling.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Navy picked up and safely returned to shore more 200 survivors, including many women and children. A published account in the Newport Mercury reported that “the air was warm and the sea was calm, so that those in the boats did not suffer severely.”his When they arrived at the Government Pier in Newport, survivors were taken to the Naval Station, the Naval Hospital or in many cases, to private homes in the city. Among those sheltering survivors were members of prominent families who opened their spacious mansions. These included Mrs. French Vanderbilt (mother of Rhode Island Governor William Vanderbilt), Mrs. Alexander Hamilton Rice, Mrs. Arthur Curtiss James, Mrs. R. Livingston Beeckman, and Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt, Jr., whose son was a well-known newspaper correspondent and who was on hand to report the event. The Naval War College archives contain a number of official photographs taken of the survivors as they left the military facilities.

On December 14, 2017, the War College Museum dedicated an extensive exhibit honoring Admiral William Sims, who commanded American Naval forces in Europe following the U.S. entry into the conflict. Among the artifacts on display are memorabilia relating to the U-53’s visit, as well as a handsome model of the submarine and a torpedo gyroscope recovered when the U-boat was broken up after the war. The display also includes several images of the survivors of the German attack of the American coast.

The entire incident infuriated the British. The Germans had the audacity to pull into Newport, blatantly gather strategic information (and publicity), and depart unmolested to continue their war patrol, with the neutral Americans not legally allowed to take direct action against them.

Even though Rose had, in the minds of many, acted as an officer and a gentleman at all times, the American government was also displeased. President Woodrow Wilson told German ambassador von Bergstorff that sinking neutral ships in America’s backyard (even though outside territorial limits) was not acceptable. After some fancy American diplomatic footwork over the affair, the British calmed down.

As the war went on, the U-boats suffered extensive losses. However, both Rose and U-53 survived.

Rose ended his submarine career as the fifth highest World War I German submarine ace, sinking 79 merchant ships and one American destroyer, USS Jacob Jones DD-61. He had put the U-53 into commission in1916 and served as her commander until August of 1918 when he was transferred to another assignment. While he earned a reputation as an aggressive and successful U-boat skipper, he was also known for his humanity in a war where some U-boat commanders exhibited ruthlessness. Rose would sometimes tow lifeboats from torpedoed ships until they were in sight of land. In the case of the sinking of the Jacob Jones, he took aboard his boat two seriously wounded sailors, then radioed the position of the survivors to the British naval station at Queenstown and asked that help be sent. In a touch of irony, the skipper of the Jacob Jones, Commander David Bagley, had been aboard one of the destroyers that had responded to Rose’s sinking of the merchant ships off Nantucket back in 1916.

Some of the rescued passengers from one of the British liners after it was sunk by U-53 off Nantucket (Naval War College Museum)

Rose received a number of awards and medals during his fifteen years of naval service, including in 1917 Germany’s highest medal for valor, the Pour le Merite (oddly, using a French name for the award). Rose left the German navy at the end of World War I with the rank of Korvettenkapitan (Junior Commander). He was briefly recalled to active duty in the early days of World War II to serve as a training officer. He eventually left the service with the rank of Fregattenkapitan (one level above the rank he held in World War I) and went into private industry. He died in 1969.

A female passenger rest on her luggage after being rescued at sea after the British liner she was on was sunk by U-53 off Nantucket (Naval War College Museum)

The crew of U-53 surrendered to the Allies on December 1, 1918. The U-boat was broken up in Swansea, England in 1922.

[Banner image: The crew of U-53, which visited Newport in 1916. Rose is the third officer in from the right (Naval War College Museum)]

The writer extends a special note of thanks to the staff of the Naval War College Archives and the War College Museum for their generous assistance in locating images and reference materials related to this article.

Sources:

German Submarine Activities on the Atlantic Coast of the United States and Canada, Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, 1920, pp. 18-23. (A PDF of this publication can be found on the website of the Federation of American Scientists at https://fas.org/man/eprint/german-subs.pdf)

US Naval Institute Naval History Blog, “German Skipper Showed Compassion, Humor to His Foes,” Dec. 12, 2006, www.navalhistory.org

“U-Boat War Comes to America”, Leslie’s Weekly, Oct. 19, 1916, 424.

“German Submarine Sinks Six Ships off Nantucket,” Boston Post, Oct. 9, 1916, 1.

“German War Submarine Here”, Newport Mercury, Oct. 14, 1916, 1.

“German U-Boat Reaches Newport,” New York Sunday Times, Oct. 8, 1916, 1-2.

“Second Visit Here on an Armed U-Boat,” New York Times, June 4, 1918.

“Visit of U-boat 53 to Newport Recalled,” Newport Mercury, Sept. 15, 1939, 6.

For the vital statistics of U-53, see www.wikipedia/org/wiki/SM_U-53

For a biography of Klt. Hans Rose, see www.uboat.net/wwi/boats/index.html?boat=53

For more on Klt. Hans Rose, see www.uboat.net/men/commanders/273.html

Robert K. Massie, Castles of Steel (New York: Random House, 2003).

Douglas Botting, The U-Boats (Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1979).

Lawrence Perry, Our Navy in the War (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1918).

Edwin A. Gray, The Killing Time- The German U-Boats 1914-1918 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1972).

William Bell Clark, When the U-Boats Came to America (New York: Little, Brown, 1929).

An excellent piece of rare 16mm film on World War I German U-boats, produced by FestungNorwegen.com, can be found on the following site: