No doubt about it, in the decades leading up to the Civil War, a small, but dedicated group of African-American activists, including George Downing of Newport and Ichabod Northup, Ransom Parker and James Jefferson of Providence, advocated for the rights of citizenship to be extended to all Rhode Islanders. Fifteen years earlier, in November 1841, Northup and Parker, both long-time residents of Providence, petitioned what was known as the Landholders’ Constitutional Convention for “equal participation in the rights and privileges of citizenship.” A month earlier, Northup, with the help of Alexander Crummell, a young black minister at Christ’s Church in Providence, wrote a strongly worded petition to the People’s Convention put on by the Rhode Island Suffrage Association calling for the removal of a “white only” clause from voting rules. In line with many northern states during the second and third decades of the nineteenth century, Rhode Island had barred black citizens from voting. By 1828 the black citizens of the state began to petition for the return of the franchise they once enjoyed. With the establishment of the Suffrage Association in 1840, blacks believed that they too would be included in the powerful reform movement. They were sorely disappointed however, when they learned that the final version of the “People’s Constitution” excluded blacks from voting. Spurned by the Suffrage Party, black communities across the state backed the existing Charter government during the upheaval of what became known as the Dorr Rebellion in the spring of 1842.

The activism of Northup and Ransom eventually paid off in the wake of the Dorr Rebellion, as Rhode Island became the only state in the antebellum period to re-enfranchise African Americans. Following the short-lived rebellion, blacks were re-instated with full voting privileges in a newly drafted constitution.[1] However, Northup and Ransom were not finished. Adopting the equal rights language of the Dorrites, Northup and Ransom, shifted their efforts to integration of public schools in Providence, Bristol and Newport where the greatest population of African Americans resided.[2] Colored schools in these three coastal communities were inferior to their white counterparts and black students were barred altogether from attending high school. Many of the same reformers who were successful in regaining the franchise in the fall of 1842 for black Rhode Islanders were now intent on securing a fair education for their children.

In the late 1850s, George Downing (1819-1903), owner of a successful hotel in Newport and a catering business in Providence, along with Jefferson, Northup and Parker, began a protracted battle for equal school rights and the removal of what they labeled the “remnant of slavery and barbarism.” As George Henry, a prosperous citizen in Providence’s black community, noted “my proposal was to petition the General Assembly that my child should go to school in my own ward, where I pay taxes and vote.”[3] In 1854, Downing, a graduate of Hamilton College in New York, opened the Sea Girt Hotel in Newport. A year later he was corresponding with Charles Sumner and others in nearby Massachusetts where school desegregation had already taken place. By 1857, Downing embarked on a plan to provide equal access to education. Downing, better able financially than his fellow associates, underwrote the cost of their campaign.[4] As Downing’s daughter noted in a brief sketch of her father’s life, his “efforts in his adopted state, Rhode Island, were signally effective.

It was mainly through Downing’s efforts that desegregation in the public schools was abolished. For twelve years he besieged the legislature, till victory was won, he and others at the time refused to support the Republican party’s nominees and put up their own candidates, making the school question an issue.”[5] Downing was by all standards of his day a respected and successful businessman. His hotel and catering businesses catered to the elite of society, but his skin color barred him from full acceptance into elite society. As the late Rhode Island historians Charles and Tess Hoffman noted, “Downing had learned a hard lesson—that the white power structure of Newport and Providence would continue to do business with him, but they would not invite him into their homes and clubs nor his children into their schools.”

Undeterred by social proscription Downing and his fellow activists lobbied for equality before the law. In a public letter entitled “Will the General Assembly Put Down Caste Schools?” black reformers detailed their grievances. They noted the inferior schoolhouses their children attended and the indifferent teachers assigned to these schools. However, their main point was that even if their schools were on par with the white-only schools, they would still protest as separate schools “set us apart, make us a proscribe class, and thereby cause us to feel …. as an inferior, a despised class to be looked down upon.”[6]

In January 1858, Downing representing all the memorialists on their petition to abolish school segregation, testified before the General Assembly’s House Committee on Education. Also appearing before the Committee, but in opposition to the petition were Reverend Samuel Wolcott and Charles Parkhurst, Esq., who “spoke of the efficiency and the great good accomplished by the colored schools in this city, and thought their abolition would prove detrimental to the best interest of those sought to be benefited thereby.”[7]

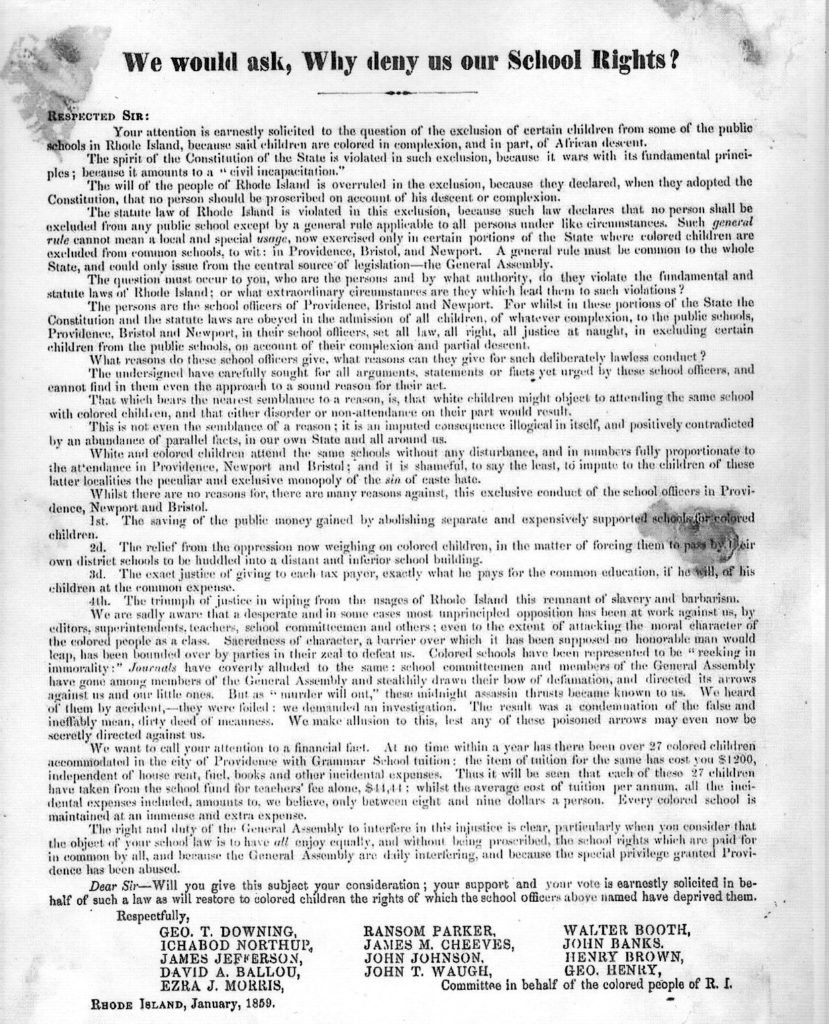

The following month the Committee on Education referred the memorial back to the full House without any recommendation. There was no action on the part of the Assembly for the remainder of the legislative session. Undeterred, the reformers sought redress with the Providence School Committee, but that too proved unsuccessful. “We shall not desist until we obtain our rights,” declared Downing, Jefferson, Northup and Parker in 1859. A broadside issued by a committee on behalf of the colored people of Rhode Island noted when referring to the segregation still practiced in Providence, Newport and Bristol that the “will of the people of Rhode Island is overruled in the exclusion, because they declared, when they adopted the Constitution, that no person should be proscribed on account of his descent or complexion.”[8] (Figure 1)

An 1859 broadside calling for an end to segregation in the school systems of Providence, Newport and Bristol (John Hay Library, Brown University)

In another handbill from 1859, Northup called on white citizens to recognize that the state had no “truer sons, either in war or peace.”[9] Northup referenced the efforts of his own father during the American Revolution.[10] He urged citizens to reject the U.S. Supreme Court’s recent ruling in Dred Scott v. Sanford (1857) that stated African Americans had no rights—a ruling that white citizens were required to respect. At a meeting of the Rhode Island Anti-Slavery Society, Downing called on New England abolitionists to devote energy to the school question. Downing even went so far as to ask the state to pay for the expense of his children’s schooling as they were excluded from public schools.[11] A formal petition for equal rights was then made to the General Assembly. The editors of the Providence Journal were opposed to the idea and argued in response that “social equality” was not something the city’s school committee should be worried about. In January 1860, another petition was sent to the Assembly calling for the enactment of a law by which “all the inhabitants of the state may be secured in the enjoyment of their public school rights.” The racist editorial board of the Providence Evening Press was thrilled when the “amalgamation school bill,” as they labeled it, went down to defeat in February 1860.

In 1862, as the nation’s leading abolitionists continued to urge President Abraham Lincoln to issue an emancipation proclamation, Northup, Ransom, and Jefferson called upon the General Assembly to “remove” what they labeled as the “last remaining relic of Slavery.” Calling for their “constitutional rights,” the petitioners demanded equal protection of the laws. Segregation was damaging to their children’s “intellectual and moral improvement” and needed to end. In January 1864, a petition written by Francis Jackson, a black waiter from Providence, and signed by over 370 other black citizens, was sent to the Assembly. “We the undersigned Colored Citizens would respectfully represent, that we are deprived of our just and Constitutional rights. Our Children are deprived of equal School privileges with the children of white citizens. They are subjected to hardships that others residing in the same districts are not. They are forced to walk long distances to reach the proscribed schools assigned them and are deprived of the advantages of the High School altogether.” In language similar to that used by the NAACP in the 1940s and ’50s, the petition declared that black children were “suffering from a feeling of social degradation” and did not receive the “benefit” that arises from “equal” education.

The large petition prompted the Committee on Education to hold public hearings throughout the year. Recognizing the monumental changes that had been brought about by the Civil War and the civil rights bills being debated in the U.S. Congress, a minority report from the Committee declared that the “great events of the time” are all “in favor of the elevation of the colored man.” They are all “tending to merge the distinctions of race and of class in the common brotherhood of humanity. They have already declared the negro and the white man to be equal before the law; and the privileges here asked for by these petitioners are simply a necessary result of this recognized equality.” A.M. Gammell and Charles Holbrook proposed a bill that mandated that “no distinction shall be made on account of race, color or religious opinions,” for admittance to schools in the state. However, in the end the committee, led by Republican Senator James DeWolf Perry of Bristol, the grandson of the notorious slave trader James DeWolf, recommended that each city and town be allowed to choose whether or not to integrate.

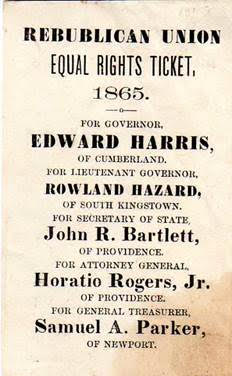

In 1865, frustrated by the lip service their petitions had received over the years and especially feeling rebuked by Governor James Smith, Downing published an “Address to Negro Voters” backing a different slate of candidates in the April election of general officers. A Republican Union ticket under the banner of Equal Rights proposed two well-known abolitionists, Edward Harris and Rowland G. Hazard, for governor and lieutenant governor. (Figure 2) However, the defection from the mainstream Republican ticket failed and Smith was re-elected by a wide margin.

By the fall of 1865 Newport’s School Committee under the chairmanship of Thomas Wentworth Higginson, a noted abolitionist, Civil War general and personal friend of Downing, voted to abolish its colored schools. With its colored schools in deplorable condition, the town of Bristol opted to close them rather than incur the cost of repair, thus leaving Providence as the only school system in the state with segregated education. With the intense debate in the U.S. Congress over a monumental civil rights bill, the tide of opinion within the General Assembly began to change. On March 7, 1866, the Rhode Island General Assembly finally passed a statute that mandated that “no distinction be made on account of the race or color of the applicant.” A decade’s worth of activism had finally paid off.

[Banner Image: Students in the Adams School in Ypsilanti, Michigan still attended segregated schools in 1907, the year of this photograph (Ypsilanti Historical Society)]For more on George Downing, click on the following link for one our previous articles, Patrick T. Conley’s “George T. Downing: Rhode Island’s Most Prominent African American Leader”:

Bibliography

Bartlett, Irving H., From Slave to Citizen: The Story of the Negro in Rhode Island, Providence, RI: Urban League, 1954.

Chaput, Erik J., and Russell J. DeSimone. “Strange Bedfellows: The Politics of Race in Antebellum Rhode Island.” Common-Place 10, no. 2 (January 2010), at www.common-place-archives.org/vol-10/no-02/chaput-desimone/.

Cottrol, Robert J. The Afro-Yankees: Providence’s Black Community in the Antebellum Era. (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1982).

Downing, George T. et. al, To the Friends of Equal Rights in Rhode Island, privately published, 1865.

Grossman, Lawrence. “George T. Downing and Desegregation of Rhode Island Public Schools, 1855-1865.” Rhode Island History 36 (November 1977), 98-105.

Henry, George. The Life of George Henry. Together with a Brief History of the Colored People in America (Providence, RI: H.I. Gould & Co., 1894).

Washington, S.A.M. George Thomas Downing: Sketch of His Life and Times (Newport, RI: Milne Printery, 1910).

Weeden, J.E. Speech of … in the House of Representatives …on Equal School Rights of Colored Children (Providence: A. Crawford Greene, 1865).

Endnotes

[1] For a detailed account of black re-enfranchisement in Rhode Island see: Erik Chaput and Russell DeSimone “Strange Bedfellows: The Politics of Race in Antebellum Rhode Island,” Common-Place 10, no. 2 (January, 2010) at www.common-place-archives.org/vol-10/no-02/chaput-desimone/. [2] Most of the towns in antebellum Rhode Island had too small a colored population to accommodate colored schools; it was only in was only in the larger towns of Providence, Bristol and Newport that separate accommodations were needed. [3] Henry, The Life of George Henry, 67. [4] Grossman, “George T. Downing and Desegregation of Rhode Island Public Schools, 1855-1865,” Rhode Island History 36 (November 1977), 101. [5] Washington, George Thomas Downing, 19-20. [6] Cottrol, Afro-Yankees: Providence’s Black Community in the Antebellum Era, 96. [7] Providence Daily Journal, January 23, 1858. [8] Broadside “We would ask, Why deny us our School Rights?”, 1859. [9] See Ichabod Northup’s broadside “READ! An appeal from a colored man whose Father fought in the Revolution,” February,1859, in the Rhode Island Historical Society collections. [10] Ibid. [11] Providence Daily Post, March 1, 1859.