The United States and France have enjoyed a long and eventful relationship. We are grateful for the Comte de Rochambeau, the Marquis de Lafayette, and the Statue of Liberty given to us by France in 1886. But the two countries have sometimes eyed each other warily, as the U.S. rose on the world stage as an economic and cultural power.

Yet there was a time after World War II when people of the two countries viewed each other with deep respect and gratitude. Europe was still recovering from the war’s devastation and faced famine during the bitterly cold winter of 1947. After a postwar trip through France and Italy, journalist Drew Pearson came up with the idea of a Friendship Train filled with life-saving supplies donated by ordinary Americans. Pearson promoted the Friendship Train in his articles—and Americans responded with $40 million of food, clothing and fuel shipped to France and Italy in December 1947.

This crucial aid and its source did not go unnoticed by the French. Andre Picard, a railroad worker and war veteran, began a drive to fill forty-nine railroad cars—one boxcar for every state, plus one shared by Washington, D.C and Hawaii (which was a state at the time)—with gifts. In the end, some 52,000 gifts were donated by his fellow citizens from their meager possessions. Wines, hand crocheted doilies, worn wooden shoes, plates, dolls, paintings, ashtrays made of broken mirrors, sets of black lingerie, a church bell, even a sabre that might have belonged to Napoleon, filled the old boxcars. It was a heartfelt thank-you for American help in defeating the Nazi regime and saving many in post-war France from starvation and the political chaos that surely would have followed.

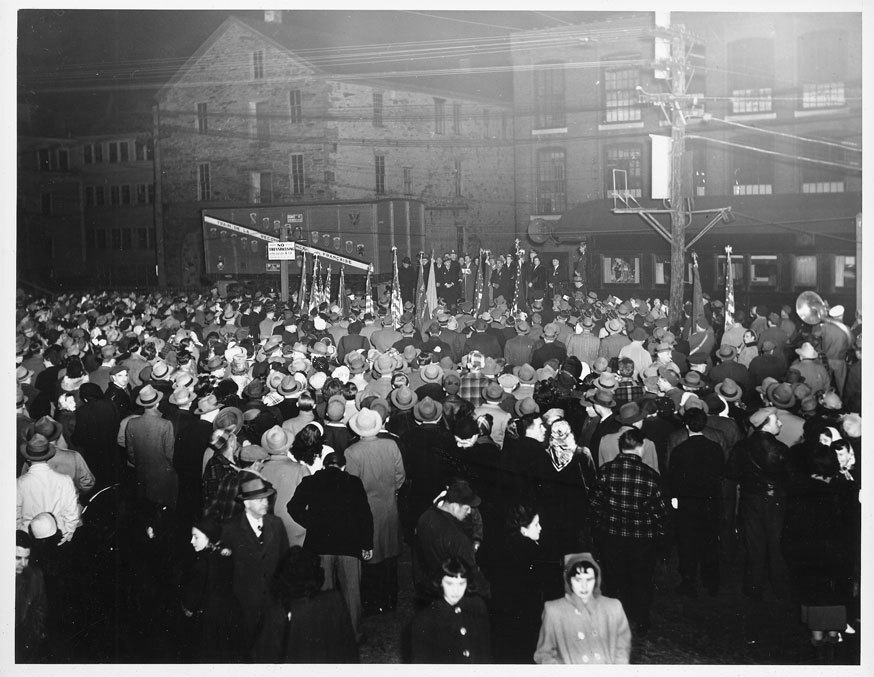

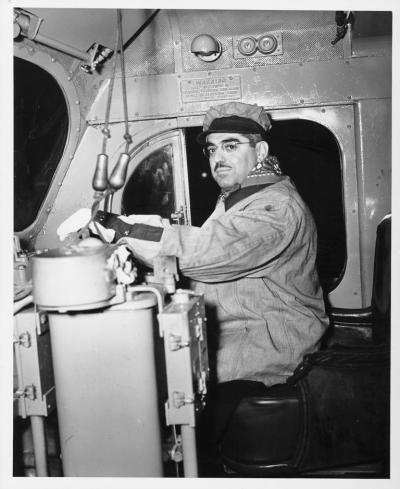

The Rhode Island Merci Train boxcar arrived at, and was accepted at, Woonsocket on February 8, 1949. Governor John O. Pastore, accompanied by bells, whistles, diplomats and soldiers in uniform, drove the fifty-two-foot-long boxcar into the Providence station under the supervision of a railroad engineer. First built in the mid-1870s for the Franco-Prussian War, the dark grey and red trains were called “40 and 8s” because they could carry forty men or eight horses.

Governor John O. Pastore at the throttle for the Merci Train boxcar, February 8, 1949 (Rhode Island State Archives)

The boxcar was displayed in front of the State House, where there was an official welcoming ceremony. Dinners were held and speeches were made. Starting on February 23, the gifts were exhibited to the public in the governor’s reception room in the State House.

The Rhode Island train carried one special treasure—a couture wedding gown with a twenty-four-inch waist, made by a dressmaker in Lyon, a city famous for its silk industry. The princess-style gown with a cathedral train, a high collar and long sleeves was made of French Jacquard brocaded satin and valued at $500, an enormous price tag in the 1940s, when the annual median family income was about $3,300.

While the gown was on display in Gladdings Department Store in Providence, the Merci Train Committee held a drawing to select a winner for this glamourous gown. But the committee set two conditions: the dress had to fit and the bride had to get married that September. A total of 104 women applied and Lillian Weimar of Westerly won the drawing. Lillian was a twenty-five-year-old clerk at the Seidner’s Mayonnaise factory in Westerly. Her father had entered her name in the drawing without informing her. Lillian, four feet ten inches tall, had the prescribed twenty-four-inch waist and a September 19th wedding date. And appropriately enough, she was born in Paris; her mother was French and her father had served with the U.S. military during World War I.

The official try-on for the dress was the 1950s equivalent of a major media event. Lillian and her mother traveled by train into Providence on August 1st and were met at the station by reporters, politicians and a representative of the French Consulate. After breakfast in the library at the State House, they proceeded to Gladdings for a fitting. According to her daughter, Janet Vetelino, on first seeing it Lillian did not like the gift of luxurious French chic; she had already bought fabric for a gown and the buttoned-up neckline was a little too prim for her taste. But it was a beautifully made, hand-stitched creation and she was proud of its connection to her native country. Even so, “she was very laid back about the whole thing,” said Janet, who took care of the dress after her mother died.

After her wedding Lillian lent the dress to a bridal fashion show, but mostly it was stored in a garment bag and was soon forgotten. After her death it was donated by her children for permanent display at the Rhode Island Historical Society’s Museum of Work and Culture in Woonsocket.

Other gifts in the Rhode Island Merci Train ranged from the mundane (a box of roll-your-own cigarette papers awarded to the Veterans Home in Bristol), to the exquisite (an eighteenth century silk fan now in the collection of the RISD Museum).

By 1949, the 40 and 8s, officially known as “Train de la Reconnaissance Française,” were considered antiques. They had been used to transport soldiers to battlefields during two world wars. Each soldier standing upright with a rifle had two square feet of space. Without seats, windows, toilets or sleeping accommodations, they were meant for the serious business of war.

While the gifts were on display in the statehouse, the train toured Rhode Island accompanied by parades and welcoming committees. It was fitted out with rubber tires so that a “float” locomotive could tow it through the cities and towns. After the buzz died down, a decision had to be made about what to do with the boxcar. It was turned over to the care of an American Legion unit in Burlingame State Park in Charlestown (the state park had been converted from a Civilian Conservation Corp camp in the 1930s to an army camp during the war).

Gifts from the Merci Train exhibited at the State House, February 1949 (Rhode Island State Archives)

When the camp was demolished the boxcar ended up on the property of Charlestown junk dealer Irving Crandall. It sat there, neglected and abused, for almost thirty years. It was open to the elements, parts were vandalized and homeless people made fires inside to keep warm.

In 1995, an East Greenwich couple, Fred and Betty Tanner, read about the train’s deplorable condition in the Providence Journal. Fred had a passion for trains—at the time, he owned the Newport Star Dinner Train. The Tanners found the train wreck at Crandall’s junkyard on Ross Hill Road and bought it for $800. They transported it to their property on Frenchtown Road hoping that someone would undertake its renovation. In 1998 French émigré Jacques Staelen of North Smithfield and Alphonse Auclair of Woonsocket, wondering what happened to the historic boxcar, tracked it down and found it on the Tanners’ property. Staelen described it as “more charcoal than wood.” The Tanners donated the relic to the Rhode Island Historical Society and in 1999, fifty years after it first arrived, the train was transported at their expense, from East Greenwich to Woonsocket with much pomp and ceremony.

The northern Rhode Island mill city was an appropriate home for the Merci Train. Woonsocket called itself “la ville la plus Française aux Ḗtats Unis”—the most French city in the United States. French-Canadian immigration to Woonsocket had begun in the 1840s. As late as the 1950s seventy-five percent of the city’s population was of French-Canadian heritage. And it was a close-knit community that fought to retain use of the French language in public, and maintained a culture that centered on family and the Catholic Church. The textile manufacturing city supported French-language newspapers, radio stations and movies.

Before it could be displayed with any civic pride, the Merci Train needed serious repairs. Students in a Construction Technology class at Woonsocket Career & Technical Center, as well as those at the Paul Primavera Education Center in Bellingham, Massachusetts, tackled the extensive repair and restoration project. The rotted cedar side panels and the oak floorboards were stripped off and the steel frame was sandblasted. The missing wheels were not replaced. Thirty-five shields representing French regions that contributed the gifts are arranged diagonally on both sides of the train. Thirty-three of the original shields were donated by a Westerly doctor who found them in an antique shop and realized what they were after also reading about the train in the Providence Journal.

Finally, in 2005, the ancient car, looking much as it did in 1949, was installed in the Lt. Georges Dubois Veteran’s Wing of the Rhode Island Historical Society’s Museum of Work and Culture in Woonsocket. Even that was a challenge. The 10½-foot wide car was cut in half lengthwise so that it could be eased through the 6½-foot wide museum door. Then it was welded together around a wood post that supports the building. It currently stands in a space designed to look like a rural French railroad station.

Surprisingly, Fred Tanner believes that the museum’s restoration “totally destroyed the car.” In an e-mail from the Dominican Republic where he now lives, Tanner wrote that when he and his late wife visited the museum they were “horrified at the demise of this great historical treasure.” He believes that for its age and use the train was in remarkably good condition and should have been restored, not completely rebuilt. He was also appalled that the museum considered selling pieces of the original boxcar in its gift shop.

It should be noted that Italy and the Netherlands also sent tokens of appreciation for American aid during the grim winter of 1947. But their gifts were monumental, government to government. They were not the personal, everyday objects that were distributed directly from the French people to the Americans. Italy sent four huge bronze men and horse sculptures in the Art Moderne style. In the early 1950s they were installed on the abutments of the Arlington Memorial Bridge and Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Bridge in Washington, D.C. In 1954 the Netherlands also expressed appreciation with the gift of a forty-nine bell carillon that can be heard daily near the United States Marine Memorial in Arlington Ridge Park across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C.

[Banner Image: Rhode Islanders greet the Merci Train, probably on February 8, 1949, in Woonsocket (Rhode Island State Archives)]Bibliography

Providence Journal, Aug. 14, 1995

Providence Sunday Journal, Feb. 2, 1999

Woonsocket Call, February 21, 1999

Valley Breeze, January 27, 2005

Good Old Days Magazine, Jan/Feb 2013

www.Mercitrain.org

U.S. Government, Bureau of Labor Statistics

A special thank you to each of (i) Janet Vetelino, who shared memories of her mother’s wedding dress and donated it to the Museum of Work and Culture after Lillian’s death, (ii) Irene Blais at the Museum of Work and Culture, who has collected a folder full of newspaper articles about the Merci Train, which she generously loaned to the author, and (iii) Fred Tanner, who took time from his church volunteer work in the Dominican Republic to write about his involvement with the Merci Train.