“We sometimes speak of stubborn facts. Nonsense! A fact is a mere babe when compared with a stubborn theory.” – Samuel McChord Crothers

On October 7, 2017, the Hopkinton Land Trust formally dedicated its newest property, the Manitou Hassannash Preserve. The five-hour program included a ceremony conducted by Native Americans and a keynote address, “Let the Landscape Speak for Itself,” by Doug Harris, deputy historic preservation officer for the Narragansett Indian Tribe.[1]

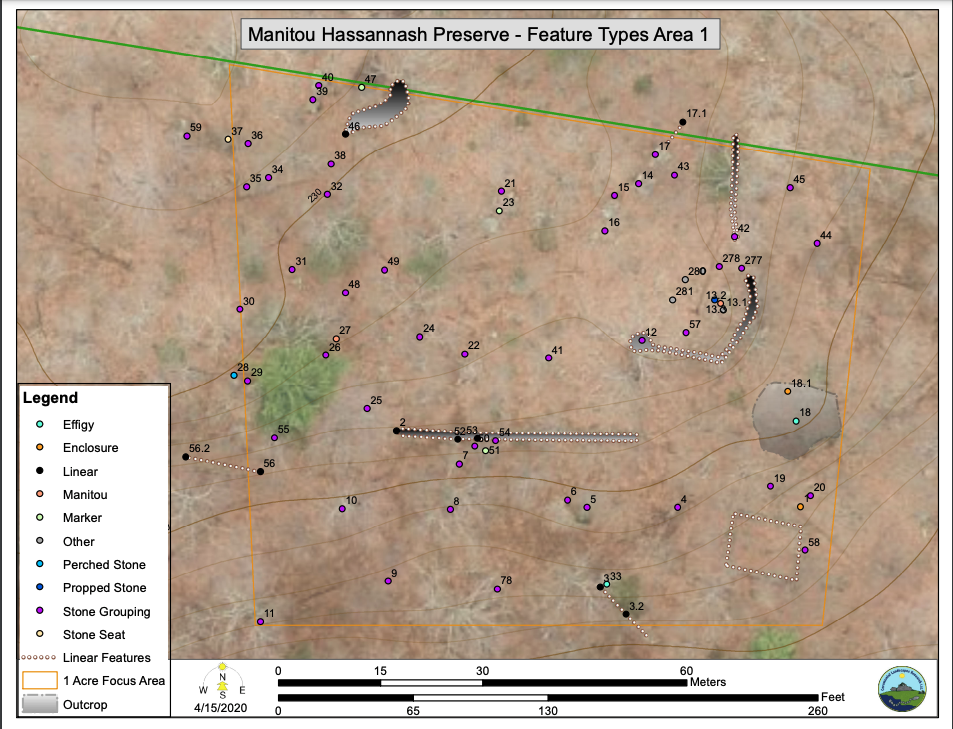

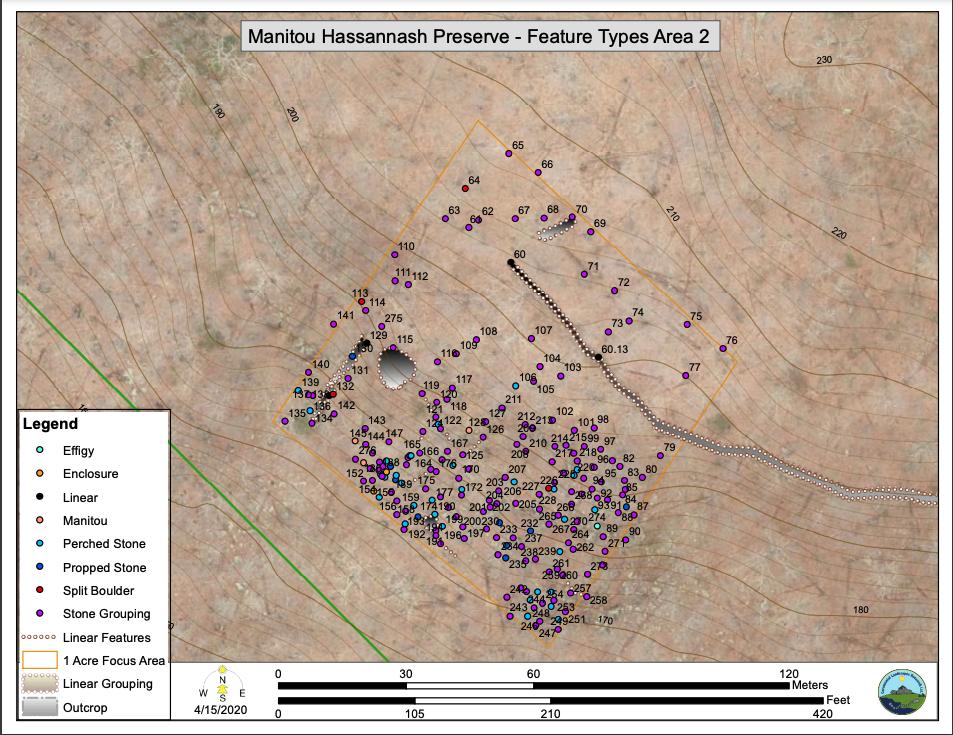

Manitou Hassannash Preserve (“spirit stone grouping”) covers 13.3 acres in the Canonchet area of Hopkinton. The lot owned by the land trust, and lots adjacent to it, contain more than two thousand hand-laid stone structures, including stone piles, standing stones, split and filled boulders, enclosures, chambers, and rows of stones.

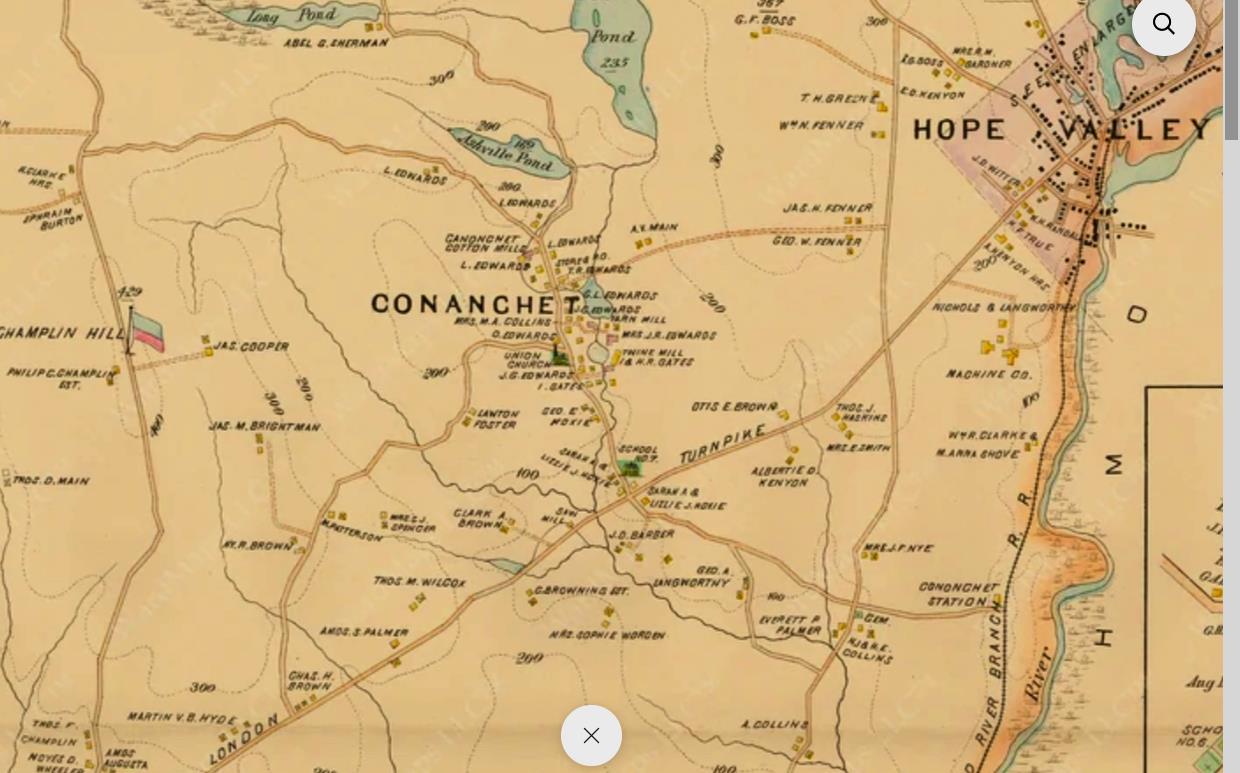

This detail of an 1895 map of Hopkinton shows the location of Canonchet (misspelled Cananchet in the map) (Everts and Richards’s Atlas of Southern Rhode Island)

The land trust, a municipal body, paid $280,000 for the property in 2014, after the prior owners had applied to the town for approval to create a new building lot on it. The people responsible for purchasing, preserving, and dedicating Manitou Hassannash believe it contains a ceremonial stone landscape built by Native Americans for religious rituals, and that many of the stone structures are animal effigies, commonly serpents or turtles; walls with niches for placement of perishable offerings to the spirits; and split stones used as symbolic entrances to the underworld.

The upland forests of the northeastern United States contain hundreds of clusters of stone structures, rock piles, and cairn fields, so it isn’t unusual for a conservation organization to own land with such structures. What’s remarkable about the Hopkinton property is not only that it was purchased for the specific purpose of preserving the stone structures on it, but that the decision to purchase the property was made without the endorsement of a professional archaeologist. The identification of the stone structures as Indigenous and ceremonial was made by local amateur historians, avocational ceremonial stone landscape activists, and Harris, the deputy tribal historic preservation officer.

The cemetery is the Thomas Brightman Lot, Rhode Island Historical Cemetery HO52, located off Lawton Foster Road North in Hopkinton. (Photo by Paul Ziobro, courtesy of CLR)

Until the 1980s, few people were interested in the stone piles found in upland forests. Most professional archaeologists believed the stone piles were left by farmers. In 1989, however, Byron E. Dix, an engineer, and James W. Mavor, Jr., a naval architect, published Manitou: The Sacred Landscape of New England’s Native Civilization. Dix and Mavor theorized that most of the stone structures found in New England forests were built in the pre-colonial period by Native Americans for ceremonial purposes, and to correctly identify them, the observer had to be willing to ignore archaeological orthodoxy. Manitou helped to inspire widespread interest in stone landscapes among antiquarians and avocational archaeologists. The New England Antiquities Research Association (NEARA)[2], founded in 1964 by avocational students of stone structures, embraced Dix and Mavor’s theory of pre-colonial Indigenous construction. Dozens of websites and blogs are now devoted to the study of these stone structures. In a 2016 article in the Journal of Ohio Archaeology, two professional archaeologists said that “the most comprehensive, ongoing rock feature research in the northeastern United States is not being conducted by professional archaeologists. The websites and publications of [NEARA], a group of primarily ‘amateur’ rock feature researchers, and of historian mother-and-son team Mary and James Gage, are far more comprehensive than the vast majority of modern archaeological publications.”

Many ceremonial stone landscape activists share an antipathy toward professional archaeology, and many agree with the position of most tribes that only Native Americans have the right to accurately identify these structures. In a resolution adopted in 2007, the United South and Eastern Tribes, Inc. stated that these structures have been used for centuries “to sustain the people’s reliance on Mother Earth and the spirit energies of balance and harmony,” and that professional archaeologists and state historic preservation officers often mistake these structures “as the efforts of farmers clearing stones for agricultural or wall building purposes,” dismiss them as insignificant, and allow them to be destroyed during development projects. Bettina Washington, tribal historic preservation officer for the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah), has said, “We do not allow non-tribal representatives to determine what is culturally relevant to our People, no matter how esteemed or how many letters follow their names.”

The National Park Service (NPS) has wholeheartedly embraced the position that a tribe’s identification of a group of stones as a ceremonial stone landscape is sufficient by itself to authenticate the nature and origin of a site. In 2008, the National Register of Historic Places found that a group of stones in Turner’s Falls, Massachusetts is a sacred ceremonial area that satisfies the criteria for placement on the national register, despite a state historic preservation officer’s determination that the site is an unfinished stone wall. In a 2017 NPS on-line publication called “Acknowledging Landscapes: Presentations from the National Register Landscape Initiative,” the NPS states:

Tribal oral histories reveal the cultural contexts of ancient ceremonial landscape features. Understanding the contexts enhances perceptions of the cultural values of landscapes shared by Native Americans from the Atlantic to the Pacific. An elder medicine man said not to rely on tribal oral history or tribal lore alone. What you must do is let the landscape speak for itself and let the tribal oral history and lore stand as witness.

Some professional archaeologists and anthropologists do support the ceremonial stone landscape movement’s core beliefs. Curtiss Hoffman, Professor Emeritus of Anthropology at Bridgewater (Massachusetts) State University, is one of the most prominent academic advocates for the movement. In Stone Prayers: Native American Constructions of the Eastern Seaboard, published in 2018, Hoffman describes the years of research he conducted “to provide quantitative support for the indigenous construction hypothesis.” Hoffman analyzed the location, arrangement, density, soil type, elevation, and proximity to stream headwaters or watersheds of 18 basic types of rock formations on more than 5,500 sites. He says his mathematical analysis of the data shows that the structures were not randomly constructed.

For many professional archaeologists, however, the assurances of a tribal elder are not sufficient evidence that a stone structure was built by Indigenous people. Archaeologists have developed several methods to determine the probable age and origin of stone structures.

Stone feature at Manitou Hassannash Preserve in Hopkinton—a serpent (002.2.1) (Photo by Paul Ziobro, courtesy of CLR)

Speaking before the Richmond Planning Board on July 13, 2021, Joseph N. Waller, Jr., a senior archaeologist at the Public Archaeology Laboratory, Inc. of Pawtucket, Rhode Island, explained how he determined that the stone piles on a client’s property in Richmond were not of Native American origin. Waller, who has deep expertise in the history and archeology of the Narragansett Indian Country, said he researched the history of the property, examined it with LiDAR (light detection and ranging, which uses pulsed radar to create a three-dimensional image), mapped the GPS location of each stone feature, spoke to the Narragansett Indian Tribe’s historic preservation officer, and examined each stone feature to determine whether it had a “metallic signature” that would be consistent with Native American occupation. The presence of brass and copper would suggest Native American origin. He said 10% to 20% of the stone features on this property had a metallic signature. When he inspected the ones that could be investigated without disturbing the integrity of the stone feature itself, he found iron spikes, plate metal, angle irons, or iron slag, all consistent with 19th century agricultural use of the property. A Planning Board member asked Waller if it is possible to determine if a stone feature is Native American in origin just by looking at how it is built. Waller said it is not. He said some stone piles are of agricultural origin while some are what the Narragansett Indians have described to him as memory piles or prayer piles. He added that no stone structure should be disturbed before its origin is determined.

As the ceremonial stone landscape movement has gained momentum, any professional archaeologist with the audacity to suggest that some ceremonial stone landscapes are not, in fact, ceremonial stone landscapes, is likely to be labeled as racist who is disrespectful of Indigenous culture. What kind of professional archaeologist would be willing to subject himself to that kind of public criticism?

In 2013, Timothy H. Ives, who is currently Rhode Island’s state archaeologist, published an article in the professional journal Northeast Anthropology called “Remembering Stone Piles in

New England.” It was followed by “Cairnfields in New England’s Forgotten Pastures,” published in Archaeology of Eastern North America in 2015. Both articles advanced the theory that most stone structures in upland forests were built by farmers in the 1800s to contain rocks and mitigate soil degradation in over-used pastures. Ives says that building stone piles was a common practice, especially in the mid-1800s when many farmers raised sheep, but gradually fell out of favor. Ives does not question the existence of stone structures that were built by Native Americans for ceremonial or spiritual purposes, but believed that most stone cairns on previously-farmed land in New England forests were built by 19th century farmers to prolong the usefulness of stony pastures overgrazed by sheep. In Rhode Island, he has said, such piles are typically located on soil unsuitable for growing crops, near farmsteads abandoned before the 1800s, and where second-growth forest has overtaken what was once a cleared farm. Ives says ceremonial stone landscape activists believe that the idea of 19th century farmers leaving heaps of stones in their fields is a white supremacist myth, and that historians and archaeologists uphold the myth to deny Indians their true religious heritage.

To say that Ives was vilified for his views would be an understatement. This e-mail, which Ives received from a NEARA member, is typical of the reaction to his first “stone piles” article: “It is distressing that you willfully ignore the documentary record of Native American stone cairns, and only manage to identify agricultural stone piles, for which there is no documentary record. None. I will be charitable and merely describe this behavior as intellectually dishonest, rather than racist as many might.” In an on-line post, NEARA member Steve DiMarzo wrote, “It is the height of elitism and disrespect for those in academia to try to tell the Narragansett Tribal Elders or for that matter any Native American Tribe what these stone structures mean! Shame on those who are still messing with the Natives 400+ years after first contact believing that they know better!”

Tribal elders and tribal historic preservation officers say that knowledge about ceremonial stone landscapes and the spiritual significance of stone have been passed down orally through the generations. But students of stone structures who dig deeply enough into the topic discover that virtually the only references to Indigenous stone structures in the Northeast in pre-1980s professional or academic literature are to stone piles, memory piles, or “taverns” constructed by the side of a road by people who pass by to memorialize a person or event associated with the location. Ives notes that the stone piles in ceremonial stone landscapes “typically occur in groups, include stones that are too heavy for flesh-and-blood humans to throw, and often exhibit the compact structure of careful placement.” He believes the ceremonial stone landscape movement “transposes the ideological mystery and power of the Indian memory pile tradition onto something that appears to be historically unrelated and far more abundant.”

A number of ceremonial stone landscape activists seem personally offended by Ives’s agricultural stone pile theory and have invested a substantial amount of time and effort in attempting to disprove it. James Gage’s article “Field Clearing: Stone Removal and Disposal Practices in Agriculture & Farming” and Mary Gage’s article “Case Study of Stone Removal Activities in Joshua Hempstead’s Diary” were published in the Bulletin of the Archaeological Society of Connecticut in 2014, and their article called “Challenging the Ives Cairnfield Formation Model” was posted on their website, Stone Structures of Northeastern United States[3], in 2021. A page on that website called “Field Clearing Sources” collects source material documenting what James Gage believes are flaws in Ives’s theory. Stone structure researcher Tim MacSweeney posted “The Process of Pasturization: A Tale of Two Tims” [NNED TO FIX] on his blog, Waking Up on Turtle Island, on March 2, 2016. An excerpt:

So, yes I’m the Other Tim, quite happy to be the Tim who sees that he is surrounded by serpent walls. I’m formally untrained in the sense that I have no degree, but I’m free to not be bound by that training, free to question the authority of the documentation, free to interpret what I think I see and speculate rather than homogenize about it ‘until the cows come home from the Euro-American pasture,’ you could say, and see how it makes sense in a Traditional Indigenous Knowledge sort of way . . . .

Anthropologists who have studied Eastern Woodland Indians apparently were not aware until the Dix and Mavor era that most of these ceremonial stone landscapes built by Indigenous people existed. Is that because tribal members kept the information a secret, as many tribal preservation officers claim? Is it because the knowledge was lost? Or is it because the belief that Indians built these structures is of recent origin? Peter Waksman, a retired software engineer from Concord, Massachusetts who maintains a blog called Rock Piles[4], has spent hours searching the forests for stone landscapes, sometime accompanied by Native Americans (including Doug Harris, the Narragansett Tribe’s deputy historic preservation officer, who is neither a native Rhode Islander nor a Narragansett), and has concluded that Native Americans did not know about these ceremonial stone structures until they were pointed out by non-Native avocational archaeologists. In a blog entry dated 1 October 2018, Waksman wrote:

I was very curious about whether the Indians already knew about ceremonial stone work . . . They did have a story about a ‘medicine man circuit’ that passed through the towns I listed [Waksman had given Harris the names of eight towns where he had found ceremonial stonework] . . . I was very puzzled by the use of quartz in rock piles and tried to pass various speculations by Doug to see what he would say. He informed me that quartz, as a white material, was more an amplifier than something with its own properties. And that is the only useful information I got from him. Also his wife, Winona, showed some puzzlement when I first showed her a rock pile, wondering if it wasn’t from field clearing and dismissing similar structures from her back yard. I really wanted to know if there was any cultural continuity between today’s Native Americans and yesterday’s rock piles. I conclude that the memories are there but vague and featureless and mostly forgotten.

During a subsequent NEARA panel discussion, Waksman wrote, the chairman of the United South and Eastern Tribes, Inc. said, “We did not know about these things . . . you showed us the way.”

If ceremonial stone landscapes can be identified based solely on the opinions of tribal historic preservation officers based on the tribes’ oral traditions, but Northeastern Native Americans didn’t know about them until recently, what is the basis for these opinions?

In 2013, when the owner of the Canonchet property now owned by the Hopkinton Land Trust first sought to subdivide it, she asked Ives, in his capacity as the state archaeologist, for his opinion on the origin and significance of the stone structures. He visited the property accompanied by Harris, at Ives’s request. In a letter dated December 12, 2013, Ives wrote, “[W]hile I cannot directly date their construction, they appear to be clearance cairns associated with past farming practices.” He added, “While I recognize and support Tribal interests in historical preservation, I cannot independently confirm Doug’s landscape interpretation because research based on historical and/or archaeological evidence is not available for this type of landscape.”

In their efforts to preserve the Canonchet site, members of the Hopkinton Historical Association, a private group, and the Hopkinton Conservation Commission, a municipal body, solicited help from Harris; DiMarzo, then the NEARA state coordinator; Mary Gage and James Gage, of Amesbury, Massachusetts; and Professor Hoffman. In a self-published e-book titled Manitou Hassannash Preserved!, Tom Helmer, a member of the historical association, describes the events that led to the land trust’s purchase of the property. In the book, Helmer, who describes himself as “a published author of a 480-page book on Colonial and Indigenous Archaeology found in a small section of Hopkinton,” says that he “chose to stand firm for tolerance of the Indigenous practices of their religion, and respect for our common cultural legacy, now entrusted to our generation’s Stewardship.” A section of the e-book called “The Narragansett Thinking on Preservation” says:

To the living culture of the Native American residents of Hopkinton, these cairns are not piles of used rocks. They are the Living Prayers of their ancestors, as spiritually alive today as the long-ago time a prayer was spoken into each rock and lovingly assembled. A portion of each prayer was a request to Mother Earth for harmony among all her creatures. What the Indigenous Peoples across America hope for is a sense of “Good Will” and Stewardship among today’s Property Owners. They cannot force this, but hope to achieve it through education.

Stone feature at Manitou Hassannash Preserve in Hopkinton—stone grouping (022.1). These photos by CLR are just of the stones at the Preserve. There are many others in the woods nearby that are not in the Preserve. (Photo by Paul Ziobro, courtesy of CLR)

Helmer recounts that when the subdivision application was before the Hopkinton Planning Board, Professor Hoffman “directly challenged the opinion of Rhode Island State’s Principal Archaeologist Dr. Timothy Ives,” but Helmer believed that Ives’s opinion “would be the deciding factor to reject all our desperation preservation efforts.” Betraying an attitude toward government that is simultaneously cynical and naive, Helmer continues,

If they were ‘Farmer Piles,’ as Dr. Ives said, he recommended the property owners should try to leave them alone, (wink-wink), but go right ahead with your plans and do whatever you want to do! The State’s Principal Archaeologist says Doug Harris is wrong. He says Doug has no evidence to prove his opinion. As for these last-minute letters, who knows who these strangers are? Are they fakes? And who is the Hopkinton Town Planning Board going to trust, when judging between similar Titles, yet expressing exactly the opposite opinion? The logical answer was clear: They would have to side with the State’s Principal Archaeologist! Seriously, how can anyone judge between conflicting, esoteric opinions? Each side’s letters are written by “Experts” All the Planning Board has is one pile of words claiming superiority over the other guy’s pile of words. Only one safe, easy choice stood out: Approve the application for the 2nd time! Hopkinton’s Planning Board will/must decide in favor of ‘Farmer Piles,’ the written opinion of Dr. Ives, the highest authority in all matters archaeological in Rhode Island. And remember, this is Rhode Island, which means to go against the flow from higher authority is to commit political suicide” (emphasis in original).

The irony of Helmer’s assertion is that other staff members at the Rhode Island Historical Preservation and Heritage Commission, Ives’s employer, did not share Ives’s opinion.

Why are ceremonial stone landscape activists so adamant in their position and so eager to criticize anyone who disagrees with them? In his book Stones of Contention, published in November 2021, Ives responds to his critics with evidence to support his position that most stone piles are remnants of agricultural activity. But the larger question he addresses is why so many people believe these stone cairns are ceremonial landscapes rather than piles of displaced rocks. Ives believes that identifying and protecting stone structures makes middle-class white liberals feel good about themselves. They know that Native Americans historically have been killed, abused, robbed, and subjugated by European-Americans, they know that some of those European-Americans probably were their ancestors, and they feel shameful about their ancestors’ actions and attitudes. Ceremonial stone landscape activism morally redeems them. Ives says:

If one dares cast aside the fashionable lens of political correctness, evidence that ceremonial stone landscape activism derives its political power from the mobilization of “white guilt” becomes glaring. Ceremonial stone landscape preservation campaigns appear to represent collective bargains negotiated across a hard socioracial line. Indian activists gain symbolic recognition, political amplification, and volunteer labor. Their white activist allies are, in turn, released from the otherwise implicit settler colonial stigma of whiteness.

One problem with this method of moral cleansing, Ives believes, is that it does not contribute to resolving cultural differences. Casting descendants of white colonial settlers in the role of oppressors and casting Indians in the role of victims perpetuates contemporary societal divisions.

Today, white New Englanders who see themselves as advocates for local Indians seem as uninterested as ever in considering just how messy and complicated their advocacy might be, or how easily negative effects can spread in the wake of good intentions. The remarkable idea of a privileged socioracial group benevolently lifting a less privileged one should always be met with remarkable skepticism.

Think of it as the “Dances With Wolves” syndrome: Lieutenant John Dunbar (Kevin Costner) is “assigned to a remote western Civil War outpost and befriends wolves and Native Americans, making him an intolerable aberration in the military.”[5] He redeems his morality by relinquishing his position of power and authority to “go Native.”

After the Hopkinton Land Trust purchased the Canonchet property, Mary Gage and James Gage, the mother-and-son team of stone structure researchers from Amesbury, Massachusetts, performed an extremely detailed analysis of the data DiMarzo and others collected at the Manitou Hassannash site and on other nearby property. The areas examined for ceremonial stone landscapes included most of the acreage comprising the farms owned by three generations of the Foster family— Lawton Foster (1767-1842), his son Jonathan (1799-1869), and his grandson Lawton II (1819-1907). Jonathan Foster was the son of Lawton Foster and Susannah Tefft. He married widow Patience Brightman, daughter of Nathan Kenyon and Sarah Tefft, in about 1818. Lawton Foster owned a 120-acre farm on both sides of what is now Route 3 in Hopkinton. Jonathan’s 50-acre farm, on the west side of what is now Lawton Foster Road North, was north of his father’s farm. Jonathan and Patience’s son Lawton II farmed 75 acres immediately north of his parents’ farm.[5]

Stone feature at Manitou Hassannash Preserve in Hopkinton—a split boulder (071.1) (Photo by Paul Ziobro, courtesy of CLR)

Stone feature at Manitou Hassannash Preserve in Hopkinton—overhead of effigy (072) (Photo by Paul Ziobro, courtesy of CLR)

These areas, as well as adjacent acreage once owned by the Brightman family, contain a number of 18th and 19th century stone walls, building foundations, and the remains of a sawmill, as well as three family cemeteries. According to the Gages, they also contain more than 2,000 cairns, or stone piles; three stone chambers; several serpent effigies; and several enclosures, spaces outlined by stone walls that delineated a sacred area where ceremonies took place.

The Gages’ self-published book, Land of a Thousand Cairns: Revival of Old-Style Ceremonies, describes their detailed analysis of the stone structures. Based on the types of structures and their proximity to each other and to streams and buildings, the Gages believe they have identified not only specific areas where Native American religious ceremonies took place, but the types of ceremonies that took place at each location.

The Gages identified more than three dozen different types of cairns ranging from the simple (one or two smaller stones on top of a boulder) to the complex (vertical walls with stone fill). They believe the diversity of designs is evidence that the cairns are not casually-built piles of rocks but ceremonial structures with particular meanings. They believe the cairns were built by Native Americans while taking part in ceremonies. Some cairns incorporate features such as niches (recessed spaces or openings covered by stones where perishable offerings are placed) or triangular stones. Some cairns are large split boulders with small stones inside the split. A split stone, according to the Gages, represents a “spirit portal to the Underworld” and the stones inside the split were left as offerings.

On Jonathan’s farm, the researchers found that “a line of large stones, some abutting each other and others closely spaced[,] were laid out in a serpentine shape, a serpent’s body. At the end is a two-rock stack, the serpent’s head.” The Gages report that several similar serpent effigies are located throughout the area , evidence that serpent ceremonies took place there.

One of the three chambers was built on a bedrock outcrop overlooking Route 3. The Gages believe the entrance is aligned with the sunrise on December 21st, indicating that it was the site of winter solstice ceremonies. They say a seasonal stream with a propped stone cairn in the middle of it probably was the site of spring rainwater ceremonies. The Gages identified a niche built into the rear wall of a root cellar that extended from a barn foundation, and note that “[b]arn root cellars did not have niches. This was a ceremonial feature built into a utilitarian structure.”

The Gages have expertise in dating different methods of stone cutting. They believe that some of the stone structures in the area were built in the pre-contact period, but many were built during the period that the Fosters were farming the land. They have determined that the stone chamber overlooking Route 3, as well as one of the serpent effigies and two of the ceremonial enclosures, could not have been built before about 1820, based on the method some of the stones used to construct them were quarried.

The Gages believe there is no plausible agricultural explanation for construction of the cairns, the chambers, or the enclosures, leading them to conclude that the property was being used for Native American religious ceremonies at the same time three generations of the Foster family occupied it. How could this be possible? The Gages say there is “a remarkably simple and logical solution to this apparent paradox.” They believe the Fosters were “Native Americans who had integrated into Euro-American society while at the same time practicing their traditional spirituality.” In other words, the Fosters were Native Americans who were “passing” as white. The Gages believe the land where their farms were located was used for Native American spiritual ceremonies before it was occupied by European Americans, and that the Fosters reestablished the ceremonial use of the property when they bought it.

The Gages acknowledge that there is no genealogical evidence that the Fosters were Native American, but add: “This is a common occurrence. In the 18th and 19th centuries many Native Americans in New England hid their ethnic identity to avoid the persistent racism of the time period. They passed themselves off as whites by adopting the outward appearances of the dominant culture. They dressed like their white neighbors, lived in wooden houses, practiced Euro-American farming and animal husbandry, and many even attended Christian religious services.”

The problem with the Gages’ theory is that while there is no genealogical or historical evidence that the Fosters were Native Americans, there is considerable genealogical and historical evidence that they were not.

Stone feature at Manitou Hassannash Preserve in Hopkinton—split boulder perched (090.4) (Photo by Paul Ziobro, courtesy of CLR)

Stone feature at Manitou Hassannash Preserve in Hopkinton—stone grouping (136.4) (Photo by Paul Ziobro, courtesy of CLR)

Due to a number of circumstances unique to Rhode Island, intermarriage between Native Americans and African Americans was not unusual in the 18th and 19th centuries. In the 18th century, Rhode Island was, relative to its size, the leading holder of enslaved Blacks in New England. Indentured Indians were likely to labor beside enslaved Blacks, especially in South County. They were drawn together not only by physical proximity but as common victims of oppression. Unions between Indians and Blacks became so common that the term “mustee,” came into use to describe a person of mixed Indian and Black ancestry. As Ruth Wallis Herndon and Ella Wilcox Sekatau have observed, during the Revolutionary War period, white record-keepers deliberately redesignated Native people as Black, replacing a cultural description with a physical one and “committing a form of documentary genocide against them.” In other places in southern New England, Native Americans were known to marry whites as well as Blacks. In Rhode Island, however, such unions were rare. There is no evidence that there were any light-skinned people of Narragansett heritage in 19th century Rhode Island who attempted to pass as white. In fact, the vast majority of mixed-race people with Narragansett ancestry in 19th century Rhode Island were of Native and African heritage, not Native and European heritage.

In 1880, the Rhode Island General Assembly bought what remained of the Narragansett Indian reservation in Charlestown in an attempt to eliminate the tribe. It was the culmination of decades of efforts to “de-tribalize” people who continued to identify themselves as Native Americans. A committee appointed to “examine the present condition of the Narragansett tribe” reported to the General Assembly in 1830 that the Narragansetts were “verging towards [a] state of complete extinction;” while the tribe claimed two hundred members, “[o]f this number however only five or six are genuine untainted Narragansetts all the rest are either clear negroes or a mixture of Indian, African and European blood.” The report concluded, “Forty years ago this was a nation of Indians; now it is a medly [sic, medley] of mongrels in which the African blood predominates.”

The probability that there were any Narragansett Indians in Rhode Island in the early 1800s who appeared to be white, or who could “pass” for white, is extremely remote. Even if such individuals existed, it is inconceivable that their neighbors would not know who they were. In 1819, the population of Hopkinton was only 1,774 and the combined population of Hopkinton, Charlestown, Richmond, and Westerly was only 6,189. Chances are that everybody knew just about everybody else in town— not only knew them, but knew who they were and where they came from.

Stone feature at Manitou Hassannash Preserve in Hopkinton—stone grouping (191.1) (Photo by Paul Ziobro, courtesy of CLR)

The commissioners appointed to administer the 1880-1884 Narragansett de-tribalization made a list of individuals entitled to share the proceeds from the sale of the reservation land. The commission conducted a series of hearings to determine the names that should be on the list. People who claimed Narragansett heritage could argue for inclusion on the list, and argue for the exclusion of others. Most of the discussion involved the identity and ethnic background of parents, grandparents, and cousins. The record of the hearings reflects virtually no references to white ancestors. The final list, known as the 1880 roll, contained the names of 324 men, women, and children. Tribal membership today is open only people who can prove descent from a person on the 1880 roll. Nobody on that roll is named Foster, Tefft, or Kenyon. If the Fosters were Narragansetts, why wasn’t their family listed on the 1880 roll? According to the Gages, it might be because the Fosters were Pequots, not Narragansetts. They say the fact that Lawton Foster was born in North Stonington, Conn. supports this explanation. However, the Foster and Lawton families were from Westerly; the first white woman believed to have settled in Westerly, in 1658, was Mary Lawton. North Stonington is adjacent to Hopkinton. The distance from Canonchet to the Connecticut state line is less than five miles. Did Lawton Foster’s parents become Indians by temporarily settling in an adjacent town across the state line?

Other evidence the Gages give to support their theory is equally speculative. They identify ceremonies that took place on the Hopkinton property by referring to practices and beliefs of the Ojibwe (Chippewa) of the northern Midwest, the Huron (Wyandot) of the northern Great Lakes, the Cherokee of the Southeast Woodlands, and the Mandan of the Great Plains, among other tribes. They believe that all Native Americans shared the same religious beliefs and conducted the same ceremonies, a belief that many professional anthropologists do not share.

There is no question that members of the Narragansett tribe have retained Native American traditions into the 21th century, but the Gages offer only lame evidence to support this. They cite a May 3, 1910 feature story in the Norwich Morning Bulletin about “the late chief, James Harris . . . a full-blooded Pequot, [and] his wife, Sarah Carlisle of Wassiac, N.Y. . . . a white girl,” who “still lives on the reservation, a fine old woman who sticks to and believes in most of the traditions of her husband’s people,”[6] and a tongue-in-cheek item published in the Bridgeport Evening Farmer in 1912 about an Indian folk tale.[7] They also note two sites they have documented: property in Charlestown occupied by the Lewis family, a mixed-race family who built an elaborate serpent effigy and ceremonial cairns in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, and property in Shelton, Conn. with a ceremonial stone landscape that was occupied between 1790 and 1880 by a free Black family with marriage ties to the Golden Hill Paugussett tribe.

The Gages assert that census data supports their theory that Lawton Foster “was a Native American living and working in the Euro-American manner while still practicing the old ceremonies.” When the 1905 Rhode Island state census was taken, they say, “Lawton the younger was vague when asked by a census taker for his religious affiliation. It hints at the possibility he did not conform to Christian practices.” Census-takers in 1905 were told to ask if each person was “Roman Catholic, Protestant, or Jew,” and if Protestant, which denomination. Lawton is listed in the census as Protestant, but, the Gages say, “other members of his household listed a denomination.”[8]

Land of a Thousand Cairns seems to rely heavily on the accuracy of census records, not only in this instance but in the sections of the book identified as family genealogies. But professional genealogists agree that census records often contain errors and should not be relied on as primary sources. U.S. censuses were hand-copied in duplicate, but the two copies often did not match either the original or each other. One analysis of the 1850 census for New Shoreham found data collection errors, simple copying errors, row-by-row copying errors, and column-by-column copying errors. People were seldom questioned individually; one person, not always the one with the best memory, usually provided information for the whole family. Some census-takers had poor penmanship and limited literacy skills, and others were just in a hurry. It is very unlikely that the 1905 census information about Lawton Foster’s religious affiliation had any particular significance. The author’s great-grandfather also was identified as Protestant in the 1905 Rhode Island census while his wife was identified as a Congregationalist, but the author is sure that her great-grandfather was not a Native American and did not take part in Indian religious ceremonies. He was probably just weeding the vegetables in the back yard on Sunday mornings while his wife and children were at church.

If, as the Gages believe, it was Lawton Foster who revived the Indigenous ceremonies or taught them to his son, he must have been an Indian. But there is no evidence that either Lawton or his wife was of Native American heritage.

In 1882, a retired Westerly farmer named George Foster submitted a brief family genealogy for publication in the Narragansett Historical Register. Foster wrote that most of the Fosters in the Westerly area were descended from three brothers— John, Thomas and Caleb— who came to Westerly from Salem, Massachusetts in about 1707. George Foster, a Quaker whose 1816 birth was recorded in the records of the South Kingstown Monthly Meeting, said he was a fifth generation descendant of John Foster and Margery Card through their son Card Foster, and he identified Lawton Foster as a descendant of John Foster and Margery Card’s son Christopher. Frederick Clifton Pierce, author of a 1,049-page Foster genealogy published in 1899, identified the John Foster who moved from Salem to Westerly as the son of Joseph2 Foster and the grandson of John1 Foster, who was born in England in 1626 and died in Salem in 1688.[9]

Lawton Foster’s mother, Anna Lawton, was the daughter of Joseph Lawton and Sarah Richmond. Joseph Lawton was a descendant of Thomas Lawton, who was born in England and settled in Portsmouth, Rhode Island, in 1639. Thomas married Elizabeth Salisbury, his son Daniel married Rebecca Mott, and his son Joseph Sr. married Mary Burrington. Anna’s mother Sarah Richmond, born in Westerly, was a descendant of John Richmond, who emigrated from Wiltshire, England about 1635 and was one of the founders of Taunton, Massachusetts. The Lawtons were members of the Society of Friends.

Lawton Foster’s wife, Susannah Tefft, was the daughter of Samuel Tefft, Jr. and Amie Gardiner. Samuel Tefft, Jr. was a descendant of John Tefft, a resident of Portsmouth by 1655. Aime Gardiner was a descendant of George Gardiner, who was in Newport by 1638.

There is no evidence that Lawton Foster’s son or his grandson or their wives were of Native American heritage. Patience Kenyon Foster, Jonathan’s wife, was the daughter of Nathan Kenyon, Jr. and Sarah Tefft. Nathan was a descendant of James Kenyon, who emigrated to Rhode Island from England and was in North Kingstown by 1670.[10] Ann (“Nancy”) Worden, the wife of Lawton Foster II, was the daughter of Benjamin Worden, Jr. and Rebecca Jones. She was a descendant of Peter Worden, who was in Yarmouth, Massachusetts by 1643.

Many of these people were related to each other by blood or marriage. Nancy Worden Foster’s great-grandmother was a Gardiner, as was Jonathan Foster’s grandmother. Amie Gardiner Tefft’s aunt Amey was married to Stephen Tefft, and Aime’s great-grandmother was Tabitha Tefft. Patience Kenyon Foster’s great-grandfather’s second wife was Mary Gardiner. Nathan Kenyon’s cousin John Kenyon married Anstis Tefft, and John Kenyon’s son George married, as his third wife, Ann Gardiner. Amie Gardiner’s great-granduncle Henry Gardiner was married to Sarah Richmond’s great-aunt Abigail Richmond. The possibility that any of these people were Native American is remote at the least.

Lawton Foster II died on November 25, 1907. His funeral took place on November 29 at Canonchet Chapel, a Seventh Day Baptist congregation.[12] According to the Gages, the practice of the “old-style ceremonies” at Canonchet died with him.

If the stone structures on the former Foster farms were not built by Native Americans during the 1800s, who built them? What purpose did they serve? Some of the stone cairns appear so intentional in their construction that it’s difficult to imagine they were built by people casually clearing stones from pastures. The cairns are so close together in some places that it would have been difficult to use the area for many practical purposes.

Two areas showing the locations and identifications of hundreds of stone structures documented within the Manitou Hassannash Preserve in Hopkinton. Many more are outside the preserve. (Maps by Eva Gibavic, courtesy of CLR)

According to the Gages, the chambers have none of the usual dimensions or features of root cellars and would have been impractical for domestic use because of their sizes and locations. What were they built for?

The rows of stones identified as serpent effigies may look like snakes to some observers, but they look to others like randomly-scattered rocks or unfinished stone walls. Ceremonial stone landscape activists seem to assume that all or most of the stones at these sites were intentionally placed at their current locations. But to make that assumption, they must ignore the fact that stone naturally moves and shifts.

Is it possible that any of these structures were built for some purpose other than those that have already been suggested? Would a thorough examination of the Canochet property by professional archaeologists yield new theories about the purposes of some of the structures?

The mystery at Canonchet may never be solved.

All photographs and maps courtesy of Ceremonial Landscape Research, LLC (see www.clresearch.org)

END NOTES

[1] Videos of the speakers are available online on YouTube at https://www.youtube.com/ (search for Manitou Hassannash Preserve). [2] New England Antiquities Research Association at http://www.neara.org/ [3] Stone Structures of Northeastern United States at https://www.stonestructures.org/index.html [4] Rock Piles at https://rockpiles.blogspot.com/ [5] Internet Movie Database at https://www.imdb.com/ [6] Neither the Gages’ book nor the report prepared for the Town of Hopkinton by Ceremonial Landscapes Research, LLC includes a map of the boundaries of the Foster family farms superimposed over the land trust property as depicted on the current tax assessor’s plat map, so it is difficult to tell exactly which part of any of the farmsteads is now part of the preserve. [7] “Basketry an Art,” Norwich Morning Bulletin (Norwich, Connecticut), May 3, 1910, 7. The story was adapted from an earlier story that ran in the New York World. [8] “Rattlers Making Merry at News of Hunters’ Lethargy: Schaghticoke Indians Tell Story of Weird Feast in Reptiles’ Den,” Bridgeport Evening Farmer (Bridgeport, Connecticut), June 3, 1912, 4. Another story on the same page, “New Wigwam of Wowompon Tribe Ready,” about the dedication of a new lodge by a local chapter of the Improved Order of Red Men, reflects the same contemporary attitude— that people claiming to be Indians were appropriate objects of humor. [9] In 1905, Lawton lived with his daughter Loanza, her husband Andrew Main, and their 13-year-old daughter Nancy. Lawton is listed as Protestant, Andrew and Loanza are listed as Baptists, and the designation for Nancy is either blank or illegible. See “Rhode Island State Census, 1905, at FamilySearch.org database with images, E.D. 253, Fam. 42 (microfilm of original documents at Rhode Island State Archives). [10] The Gages report that there was another Jonathan Foster in Westerly contemporaneously with Lawton Foster’s father Jonathan, Jr. but they identify him only as originally from Attleborough, Massachusetts and “related to the Foster family of Watch Hill.” According toPierce, he was Jonathan, born in Attleborough on June 8, 1715, the son of Major John Foster of Salem, and thus he almost certainly was a cousin of Lawton Foster.

[11] “Kinyon” is a phonetic spelling of Kenyon often used in the 18th and 19th centuries. The majority of family members in Rhode Island now use the “Kenyon” spelling. [12] “Lawton Foster Buried: Aged Canonchet Citizen Well Known in Hope Valley,” Evening Bulletin (Providence, RI), Nov. 30, 1907, 9; The Hopkinton and Charlestown R.I. Directory 1924-1925 (Providence, RI: C. DeWitt White Co., 1924), 28.SOURCES

James Gage, “Field Clearing: Stone Removal and Disposal Practices in Agriculture & Farming,” Bulletin of the Archaeological Society of Connecticut, 76:33-81 (2014).

James Gage and Mary Gage, “Challenging the Ives Cairnfield Formation Model” (2021) at https://www.stonestructures.org/index.html

Mary Gage and James Gage, Land of a Thousand Cairns: Revival of Old-Style Ceremonies, 2nd ed. (Amesbury, MA: Powwow River Books, 2020).

Mary Gage and James Gage, “How to Identify and Distinguish Native American Ceremonial Stone Structures from Historic Farm Structures,” Bulletin of the Archaeological Society of Connecticut, 77(2015), 17-40.

Ariela Gross, “Of Portuguese Origin: Litigating Identity and Citizenship among the ‘Little Races’ in Nineteenth-Century America,” Law and History Review 25 (2007), 467-512.

Thomas Helmer, Mary Gage, and James Gage, Manitou Hassannash Preserved! (Kindle Direct Publishing, 2020).

Ruth Wallis Herndon and Ella Wilcox Sekatau, “The Right to a Name: The Narragansett People and Rhode Island Officials in the Revolutionary Era,” Ethnohistory 44 (1997), 433-462.

Curtiss Hoffman, Stone Prayers: Native American Constructions of the Eastern Seaboard (Charleston, S.C.: Arcadia Publishing, 2018).

Timothy H. Ives, “Remembering Stone Piles in New England,” Northeast Anthropology, 79/80 (2015), 37–80.

Timothy H. Ives, “Cairnfields in New England’s Forgotten Pastures,” Archaeology of Eastern North America, 43 (2015), 119-132.

Timothy H. Ives, “The Hunt for Redneck Archaeology: Disentangling ‘White Guilt,’ Ceremonial Stone Landscape Activism, and Professional Archaeology in New England,” Northeast Anthropology 85/86 (2018), 47-72.

Timothy H. Ives, Stones of Contention (Nashville, Tenn.: New English Review Press, 2021).

Rhett S. Jones, “Miscegenation and Acculturation in the Narragansett Country of Rhode Island, I710-I790,” Trotter Institute Review 3 (1989), 8-16.

Timothy MacSweeney, “The Process of Pasteurization: A Tale of Two Tims” (2016) at wakinguponturtleisland.blogspot.com

Daniel R. Mandell, “The Indian’s Pedigree (1794): Indians, Folklore, and Race in Southern New England,” The William and Mary Quarterly 61 (2004), 521-538.

Charity M. Moore and Matthew Victor Weiss, “The Continuing Stone Mound Problem: Identifying and Interpreting the Ambiguous Rock Piles of the Upper Ohio Valley,” Journal of Ohio Archaeology 4 (2016), 39-71.

Norman E. Muller, “Stone Mound Investigations as of 2009,” NEARA Journal 43 (2009), 17.

John C. Pease and John M. Niles, A Gazetteer of the States of Connecticut and Rhode Island (Hartford, CT: William E. Marsh, 1819), 48.

Ann Marie Plane, Colonial intimacies : Indian Marriage in Early New England (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2000).

Report of Commission on the Affairs of the Narragansett Indians Made to the General Assembly at its January Session, 1881 (Providence, RI: E.L. Freeman & Co., 1881); Second Annual Report of Commission on the Affairs of the Narragansett Indians Made to the General Assembly at its January Session, 1882 (Providence, RI: E.L. Freeman & Co., 1882)

John A. Sainsbury, “Indian Labor in Early Rhode Island,” The New England Quarterly, 48(1975), 378-393.

Robert M. Thorson, Stone by Stone: The Magnificent History in New England’s Stone Walls (New Yok, N.Y.: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2002).

GENEALOGICAL SOURCES

James N. Arnold, Vital Record of Rhode Island, 1636-1850 (Providence, RI: Narragansett Historical Publishing Co., 1895), 7:220 (transcribed from South Kingstown Monthly Meeting records).

Gilbert S. Bahn, Patricia Warden, Rex W. Warden, The Worden surname from Peter Worden of Yarmouth to 1850 (The Author, 2002), 200-201.

Cherry Fletcher Bamberg, “Navigating the Shoals of the 1810 Census and Beyond,” Rhode Island Roots 37 (2011), 13-16.

Rev. Thomas Barber, “The Settlement of Westerly” Narragansett Historical Register (North Kingstown, RI: Narragansett Historical Publishing Co.), 1:2 (1882), 125-127.

Richard E. Coe, “Lawton Family,” typescript mss (Syracuse, NY: 1938) at familysearch.org digital images.

George Foster, “The Foster Family,” The Narragansett Historical Register (North Kingstown, RI: Narragansett Historical Publishing Co.), 1:3 (1883), 222-225.

Jeffrey Howe, “Shortcomings of the 1850 Census,” Rhode Island Roots 24 (1998), 259-264.

Howard N. Kenyon, American Kenyons : history of Kenyons and English connections of American Kenyons, genealogy of the American Kenyons of Rhode Island (Rutland, VT: The Tuttle Co., 1935), 53, 63, and 89-90.

Elva Lawton, “The Descendants of Thomas Lawton of Portsmouth, Rhode Island,” mss (New York, NY: 1949) at familysearch.org digital images.

Linda L. Mathew, “John Tefft and His Children: A Colonial Generation Gap?” Rhode Island Roots 18 (1992), 76-80.

Frederick Clifton Pierce, Foster Genealogy, Being the Record of the Posterity of Reginald Foster, 2 pts. (Chicago, Ill.: Press of W. B. Conkey Co., 1899), 2:706-708, 717.

Julia H. Quackenbush, “Lawtons of Rhode Island,” typescript (Syracuse, NY: 1939) at familysearch.org digital images.

Joshua Bailey Richmond, The Richmond family, 1594-1896, and pre-American ancestors, 1040-1594 (Boston, Massachusetts: The Author, 1897), 1, 5-7, 14, and 53.

Caroline E. Robinson, Daniel Goodwin, ed., The Gardiners of Narragansett (Providence, RI: The Editor, 1919), 5, 15, 56, and 107.

Charles H. W. Stocking, The Tefft ancestry : comprising many hitherto unpublished records of descendants of John Tefft of Portsmouth, Rhode Island (Chicago, Ill.: The Lakeside Press, 1904), 3, 6, 7, 11, and 19.

Oliver Norton Worden, Some Records of Persons by the Name of Worden (Lewisburg, Penn.: J. R. Cornelius, 1868), 32.