[Note from the editor: An updated version of this article is in a chapter of my book Machine Guns in Narragansett Bay: The Coast Guard’s War on Rumrunners (History Press, 2023). The chapter relies heavily on official and contemporary Coast Guard reports.]

Military forces fired no shots in anger in Narragansett Bay during either World War I or World War II. But during the intervening years, thousands of rounds of machine gun fire and one-pounder cannon were fired—at fellow-Americans. The intended victims were rumrunners who, using speedy powerboats, had picked up illegal liquor from large ships from Canada or Britain stationed at Rum Row—beyond the twelve-mile zone off the coast of New England and Long Island. The rumrunners, operating at night or in foggy conditions, would then try to evade U.S. Coast Guard patrols and cruise up Narragansett Bay for the assigned drop off point. Because buying and selling liquor was illegal under Prohibition laws, the profits from a successful voyage could be enormous. The criminal element took note.

The U.S. Coast Guard became the lead federal government agency in fighting the “Rum War” against bootleggers operating off the U.S. coast. The U.S. Navy actually lent it thirty-one of its destroyers to fight the bootleggers.

As explained in an article by Robert Geake previously posted on this website, the first victims of Coast Guard fire were the crew members of the fast boat Black Duck, thought to be owned by legendary criminal Carl Rettich. Rettich’s growing Rhode Island business suffered a setback in late 1929. Geake explains: “Early in the morning of December 29, a Coast Guard vessel came within sight of one of the most successful smuggling boats of the time. Named the Black Duck, and reputed to be owned by Rettich, the boat had just taken on 383 sacks of liquor from a British ship outside Narragansett Bay and twelve miles beyond U.S. territorial waters. Coast Guard Boatswain Alexander Cornell had tied his patrol boat to a buoy near The Dumplings, an outcropping of rocks off Jamestown, with the lights of Newport in the distance. Sure enough, at 2:15 in the morning, with the fog lifting, Cornell spotted the Black Duck drawing close to the harbor. He turned his searchlight on the speedy rumrunner and sounded his Klaxon horn, a signal for the boat to stop. When the Black Duck continued, he ordered the vessel strafed with machine-gun fire. The sole survivor of the boat, the pilot wounded in his hand, surrendered shortly afterward—three of his crewmen lay dead.” One more was wounded, and he was brought back to Fort Adams.

Few Rhode Islanders supported Prohibition. The state’s many Catholics thought it was a Protestant plot. Moreover, state residents were not pleased with this kind of violence occurring in their beloved bay. Cornell and the rest of the crew were brought before a Rhode Island grand jury, but avoided indictment. The “law-and-order” jury believed the crew had given the Black Duck sufficient warning to surrender before opening fire. There was also testimony that the machine gunner had, per orders, been firing ahead of the stern of the fleeing rumrunner, which had then veered off and into the path of the machine gun fire, accidentally killing the three crew members. Even so, the commandant at the New London Coast Guard headquarters was unapologetic, warning smugglers that his men “meant business.”

Law-abiding Rhode Islanders also feared that stray shots fired by Coast Guard vessels could harm or injure innocent citizens on the shore. At least one Rhode Islander complained that a stray bullet fired by the Coast Guard during one chase of a rumrunner became embedded in his house on the Sakonnet River.

Besides the ill-fated Black Duck, perhaps the most infamous rumrunner operating in Narragansett Bay was Monolola, a 30-foot powerboat. The vessel had three wild chases and its crew the same number of brushes with death by gunfire.

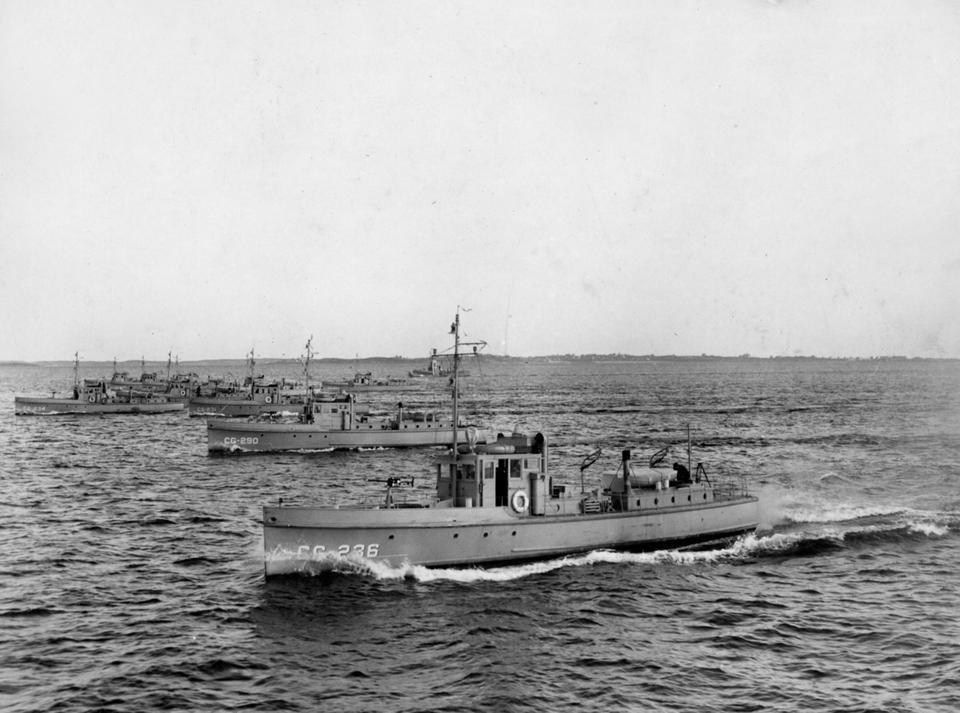

The Coast Guard’s workhorses for Prohibition enforcement were 75-foot patrol boats such as these New London-based vessels, seen in 1927. Among them is CG-290, which was later involved in the Black Duck incident. (U.S. Coast Guard)

The first incident occurred on February 28, 1930. The Coast Guard, keeping mum about the details, did not offer them to newspaper reporters, who had to rely on rumor and those who heard shots fired. It appears the Monolola was spotted entering Narragansett Bay in the morning of February 28. A Coast Guard vessel gave chase, firing its machine guns and one-pounder cannon in an attempt to stop the fleet powerboat.

According to the Newport Mercury, “It was about 11 o’clock this morning when the first shots in the chase were heard. They were reported from a number of locations. The Marine Guard on Rose Island heard them, and the government forces at the Training Station and Gould Island heard the shots, as the Coast Guard cutter repeatedly fired in an attempt to make the rum runner stop. At the time it was said the rum runner was about 200 yards in advance of the Coast Guard, both proceeding at a rapid rate.”

The newspaper report continued: “Further shots were heard from the Middletown shore, and the men on duty at the Mount Hope Bridge heard shots as the chase continued relentlessly under that structure. The farther up the bay the rum runner went, the less were its chances of escape, as there was no open water ahead. The final result was that the craft was cornered and captured.”

Before the Coast Guard could close in for the kill, the crew of the Monolola attempted to land its liquor at Salter’s Point near Fall River. But under pressure from the Coast Guard, the powerboat escaped again. By the time Coast Guard sailors found the Monolola at a dock in Fall River, its cargo, crew and registration papers were gone. It was not known if the crew had dumped the liquor in shallow water or managed to get it onshore. The Coast Guard cutter that chased the powerboat, no. 287, had been one of the vessels involved in the shooting up of Black Duck several weeks earlier. Eventually, with little proof of lawbreaking, the Monolola was released back to its owners.

The Monolola at one point on the night of February 23-24, 1931, looked like a sitting duck, but looks can sometimes be deceiving. The speedboat was spotted as it returned from “rum row,” where a British liquor supply vessel was located about twelve miles offshore. Sighted by Coast Guard cutter no. 234 at the entrance of Narragansett Bay, the chase was on. The rum runner, capable of speeds well over 30 knots an hour, compared to less than 20 by the Coast Guard vessel, easily out-distanced its rival, which fired its one-pound cannon in vain. Suddenly, near Potter’s Cove off Prudence Island, the Monolola crossed paths with another Coast Guard craft, no. 289, and the rumrunner seemed trapped.

While the Coast Guard vessels thought they had the Monolola “dead to rights,” the desperate crew on board the speedboat had other ideas. They began zig-zagging at top speed, avoiding the one-pounder and machine-gun bullets being fired at it. At one point, the speedboat came so close to the Coast Guard cutters that the sailors could read the words “Golden Wedding”—a famous brand of whiskey—on the boxes used as a barricade. After the wild chase, in which hundreds of shots were fired, the Monolola made good its escape.

The Newport Mercury reported of this incident, “Local residents watched the battle between the Coast Guard and the rum runners from the Cliff Walk and discerned the escape of a craft, which was picked up in the rays of a Coast Guard searchlight, according to report, but finally swept out to sea under a hail of bullets and disappeared.”

The motorboat was later captured, while running without lights, off Prudence Island. Its holds were inspected, but no liquor was found by the Coast Guard.

The same night, the infamous rum runner Alibi II was not so fortunate. In the early morning of February 24, a Coast Guard vessel spotted it in the Sakonnet River. After firing the usual warning shot across the bow, the rumrunner turned around and started to head back towards the open ocean. During the five-mile chase, residents of Newport and Middletown “distinctly heard” a “bombardment of one-pounder and machine-gun fire.” The Alibi II, which had previously been seized twice by authorities, had been later released pending bail. After Coast Guard patrol boat no. 235 began to gain on the heavily-laden powerboat, according to the Newport Mercury, “a flame shot from the gasoline tank, and the crew of four men immediately” jumped into a dory. The Alibi II soon burst into flames and sank. Its cargo of liquor, estimated as being worth at least $25,000, was lost. The four crew members were rescued by the Coast Guard and charges were prepared against them for violating the customs laws.

The rumrunner Nola, heavily protected by steel armor plate. It was lost in a running battle with three Coast Guard patrol boats near Vineyard Sound Lightship in December 1931 (US Coast Guard).

Whether the Alibi II was struck by cannon or machine-gun fire, thus causing it to explode, is not known for certain. The Newport Mercury was likely correct when it reported, “The Alibi II is believed to have been scuttled, owing to the fact that the craft was under government bond for two alleged previous violations of the liquor laws.” The crew probably determined that since the boat and its cargo would both be lost, it would be best for them to sink the ship so that the evidence of illegal liquor on board would disappear under the waves.

It was a busy several days. A British vessel, with a liquor cargo valued at $140,000 and sailing out of Nova Scotia, Canada, went aground the prior week on the rocks off Montauk, Long Island. The Coast Guard arranged for it to be removed from the rocks by a salvage company’s derrick. Coast Guard vessels then escorted the liquor supply vessel to New London.

Stories about the chases of the Monolola and Alibi II made front page news in dozens of newspapers across the country.

The Monolola was probably sold at auction by the federal government. As often happened when a fast rumrunner was put up for auction, the winning bidder was a rumrunner, quite possibly the same owner as before.

Almost a year later, on Monday, January 11, 1932, the Monolola had its last voyage as a rumrunner. It was again spotted and chased by a Coast Guard cutter. The Monolola was captured after an eleven mile chase by a Coast Guard cutter that had fired on the rumrunner, but without injuring anyone. Finally seized off Vineyard Sound lightship and Gay Head at 11:30 p.m., it had on board 400 to 500 cases of illegal liquor.

Four men on board the Monolola were arrested and brought, with their fast vessel, to New London. The four men gave authorities what were thought to be fictitious names. The Monolola was registered in the name of Harry Bennett of 50 Plenty Street, Providence. Fingerprints lifted from the powerboat were later identified as belonging to gangsters Joe Sousa and Robert Lawrence. (The actual owner of the boat likely was an associate of the Irish gangster Danny Walsh, who kept two luxury homes in Providence and a horse farm and mansion near the coast in Charlestown in the southern part of the state.)

Thus ended the saga of what was once described as “one of the fastest speedboats” operating in southern New England. When Prohibition ended in 1933, there was no further need for Coast Guard boats to fire at boats in Narragansett Bay or its environs.

Irving Sheldon, a member of the same Sheldon family that resided at Spindrift on the coast at Saunderstown and that gave us the World War II stories of Elisabeth Sheldon and Louise Sheldon MacDonald, still vividly remembers a summer night in the early 1930s when he saw from his family’s house on Narragansett Bay a battle between a rumrunner and a Coast Guard vessel. Irving Sheldon, now 95 years old, recalls that as a child his older brother Rhody came into his bedroom one night and woke him up so they could watch from his third floor bedroom windows the gun fight on the bay. He can remember seeing tracer bullets pierce the dark night and the red glow of bullets hot from barrel friction of a machine gun. The rumrunner was getting battered.

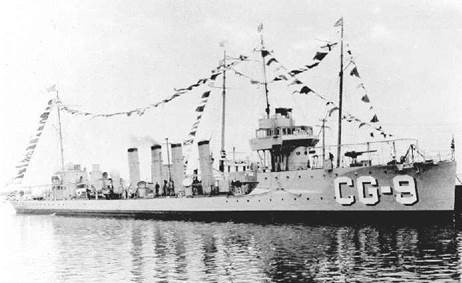

One of the Coast Guard’s new vessels in the early 1930s designed to run down rum runners (US Coast Guard)

Another Sheldon family story that may or may not involve the same incident is that the crew of bootleggers abandoned its boat and was picked up by the crew of another rumrunner. The Coast Guard vessel must have sped after the second, fleeing rumrunner, leaving the first one to drift riddled with bullet holes. The father, James Rhodes Sheldon, saw that the damaged boat had caught fire and was drifting toward a barge tied up to the Saunderstown ferry dock. This barge had a gas tank and pump used for the ferry and local recreational boats. Realizing that the fire on the damaged boat could cause the barge’s gas tank to explode, Sheldon and Wilkie, his hired employee, took out a small boat and towed the burning boat away from the gas barge. But before he left the scene, Sheldon took a wooden box from the burning boat, perhaps thinking it was illegal liquor. It turned out to have a machine gun inside of it. The family kept the gun for many years in the family’s pantry, unused, until the late 1960s when after Irving’s mother mentioned it to some Navy officers, a Navy delegation arrived the next day to take it away.

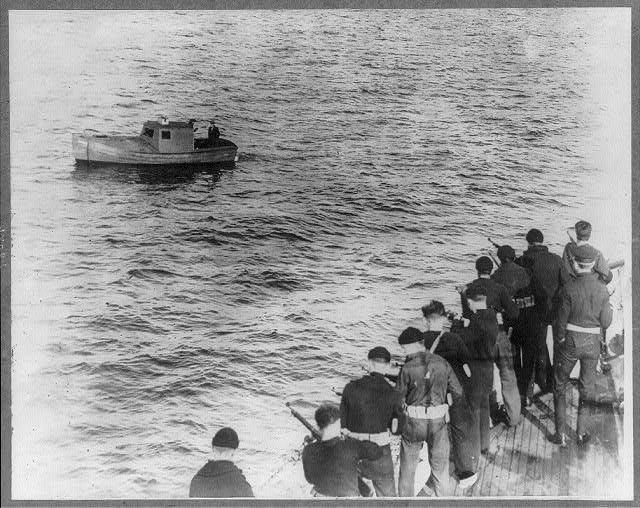

[Banner Image: James Rhodes Sheldon operating Skidaway, purportedly a former rum runner from Prohibition times that plied Narragansett Bay, circa 1938. Irving Sheldon believes it was designed by Eldredge-McInness and built at American Boatyard in East Greenwich (Elisabeth Sheldon Aschman Collection)]

Sources:

“Rum Runner Captured by Coast Guard, Exciting Chase is Staged in Newport Harbor,” Newport Mercury, Feb. 28, 1930.

“The Alibi II, Rum Runner is No More; Craft, With Cargo of Liquor on Board, Sunk by Crew,” Newport Mercury, Feb. 27, 1931

“Alleged Rum Runners, Monolola Captured,” Newport Mercury, Jan. 15, 1932

Robert A. Geake, “From Saints to Bootleggers: The Struggle for Temperance and Prohibition in Kent County, 1805-1937. Part II: Prohibition and the Gangster Carl Rettich, 1920-1937 (Feb. 25, 2015), in the Online Journal of Rhode Island History. For the link to the article, go to:

Raw Data of 160 Boats Seized Near Cape Cod and Islands During Prohibition, compiled by Ellen NicKenzie Lawson (2017), at www.smugglersbootleggersand scofflaws.com

Emails to the author from Irving Sheldon and Marjorie Sheldon, August 28 and September 1, 2017

For more on the Sheldon family at Spindrift, see Louise Sheldon MacDonald, “Growing Up at Spindrift on Narragansett Bay in the 1930s and through World War II (http://smallstatebighistory.com/growing-spindrift-narragansett-bay-1930s-world-war-ii/) and Christian McBurney, “Elisabeth Sheldon: Her Summers of 1944 and 1945 on Narragansett Bay” (http://smallstatebighistory.com/elisabeth-sheldon-summers-1944-1945-narragansett-bay/)