Although the death rate of King Philip’s War, which raged in New England from 1675 to 1676, was higher among Americans than either the American Revolution, Civil War, or World War II, its story has struggled to survive the test of time.[1] A war that saw the destruction of numerous Rhode Island towns—including Providence, Warwick, and Wickford—is not taught in many Rhode Island schools today.

Even so, the conflict between King Philip and his allied tribes and the English colonists was pivotal in Native American and English relations in New England. In fact, historian Jill Lepore sees it as the “defining moment, when any lingering, though slight possibility for [Indian] political and cultural autonomy was lost.”[2]

Thankfully, monuments and historic sites related to King Philip’s War are scattered throughout Rhode Island and serve as quiet reminders that parts of what we today call New England were once dominated by Algonquin tribes. Unfortunately, most of these monuments go unnoticed as they are dedicated to a story many have never heard.

Perhaps even more unsettling is that the monument dedicated to the Great Swamp Massacre—likely the war’s most critical battle and one that would have a lasting effect on the Narragansett tribe—is probably not placed on the actual battleground. The questionable placement of this monument has driven numerous history buffs, historians, and archeologists to search for the actual site of this battle. To fully appreciate the importance of this battle and the controversy surrounding the placement of its monument, one must first understand the role it played in King Philip’s War.

The story of the Pilgrims who first landed in America to escape religious persecution is well known, but the events that occurred after that are not so well known. After a catastrophic first winter, in which the white settlers received life-saving assistance from the Wampanoag tribe, Pilgrims began to spread out into southeastern Massachusetts in settlements. The great wave of white immigrants from England started with the Puritans, who founded Boston in 1630 and began to develop settlements throughout modern-day New England, living alongside the Algonquin tribes. According to historian James A. Warren, from about 1620 to 1650 “relations between the natives and the English were marked by mutual accommodation, peace, and growing prosperity for Indian and Puritan alike.”[3] However, as English farms began to spread to traditional Indian hunting grounds, English colonists slowly encroached on the natives’ land and showed little respect for their way of life.

Meanwhile, free thinkers like Roger Williams and Anne Hutchinson moved into Rhode Island, which was dominated by the Narragansett tribe, along with the smaller Wampanoag tribe.

The Pokanoket, a branch of Wampanoag nations, whose territory spanned what is now Bristol County in Rhode Island and lands to the east in Massachusetts, was one of the staunchest defenders of tribal rights. King Philip, the man for whom the war was named, became Sachem of the Pokanoket in 1662 after his brother was poisoned, reportedly by English colonists.[4] Although never officially proved, this incident set the tone for Philip’s relationship with the English for years to come.

Tensions reached a boiling point in early 1675 after the English thought that Philip had ordered the execution of John Sassamon, a Christian Indian who was friendly with the English. Since no English colonists were involved in the crime as either victims or witnesses, they should have allowed the Native Americans to settle the dispute independently. However, the Plymouth government aggressively (and foolishly) interceded and charged three Wampanoag Indians with killing Sassamon.[5] This encroachment on Indian affairs was an intentional insult to King Philip and was the breaking point for King Philip and the Pokanoket tribe.

Fighting first broke out on June 20, 1675, when a group of Pokanokets ransacked English homes in Swansea. Violence escalated on June 24, when nine additional Swansea colonists were killed by the Pokanoket tribe.[6] After failed peace attempts by the English, Philip and his warriors were soon joined by neighboring tribes. Indian raids spread throughout Massachusetts, Connecticut, and as far north as present-day Maine and New Hampshire. These raids were as destructive as they were horrifying. When Springfield, Massachusetts was raided by Nipmuc and Agawam Indians in October, over 300 homes were destroyed.

By December 1675, white colonists had experienced seven months of humiliating defeat and remained in constant terror. Still, what frightened colonists the most was the specter of the most numerous and strongest Algonquin tribe, the Narragansett. Its leaders watched closely on the sidelines, often giving little evidence of whether they supported the Indian rebellion or the English colonists. James Warren, in his book Gods, War, and Providence, mentions “about the best that can be said with certainty about Narragansett intentions in the fall of 1675 is that they remained ambivalent.”[7] This ambivalence did not sit well with the colonists. Therefore, with fear as their motivator, the United Colonies of New England declared war on the Narragansett people and instructed the English military to strike “with full power for the treating surprising fighting killing & effectual subduing & destroying of the Narrowganset Enemy.”[8] The colonists would shortly strike “with full power” and in a manner so devastating it is understandable why the conflict was later labeled the “Great Swamp Massacre.”

English colonists from Plymouth, Massachusetts and Connecticut attacked on December 19, 1675, in the township of South Kingstown, Rhode Island, near what is now West Kingston. English troops and about 150 Indian allies attacked a Narragansett fort on a raised piece of land surrounded by a “Great Swamp.” They were supposedly assisted by a Narragansett traitor in finding the best path through the thick swamp to the fort. Although surprised Narragansett warriors were able to defend themselves at first, the English troops eventually penetrated the fort. Once General Winslow and his troops entered the fort, the fight quickly turned in favor of the English.

The colonists were eventually instructed to burn the fort and its dwellings and storehouses. The ensuing fires forced “many Narragansett men, women, and children” to be “driven by flames and muskets to their death.”[9] The number of Narragansett “fighting men” killed that day is uncertain but estimates are as high as 700.[10] But the more unsettling calculation was made by James Warren in estimating that “four hundred noncombatants were killed…mostly by fire.”[11]

Although victorious that day, the battle caused more problems for colonists. It was the catalyst to unleashing about 1,000 Narragansett warriors into the fight as well as one of the greatest military strategists of the war, the sachem Canonchet. The colonists’ fears about Narragansetts’ ability to bolster the Indian raids were confirmed as they continued to watch as their towns were raided for the remainder of 1675 and into 1676.

Rhode Island towns found themselves utterly defenseless facing the Narragansett. Not even Roger Williams, a longtime friend of the Narragansett tribe, could stop Canonchet from raiding and destroying 100 houses in Providence (Canochet did spare the lives of Providence residents). Old Rehoboth, located in modern-day East Providence, also had its homes destroyed and supplies stolen. In Warwick, all but one of house was burnt to the ground. Pawtuxet and what is now Wickford suffered from a similar fate. By March 1676, most of the colonists ended up deserting the area south of the Pawtuxet River.[12] Many fled to Aquidneck Island.

The destruction to the colonists’ towns that ensued after the Great Swamp Massacre made the battle an important turning point. However, it would have a much longer lasting effect on the Narragansett people as they were no longer merely innocent bystanders in this war. They were now official enemies of the colonial government and were soon forced to suffer the same fate as the other Algonquin tribes who fought alongside King Philip.

By the spring of 1676, food shortages and the failing Indian leadership eventually allowed the English to take control of the war. One of the most devastating blows to the Indians came in April when Canonchet was captured near present-day Cumberland and eventually killed. This loss helped trigger the removal of the powerful Narragansett tribe from the war.[13] Then, in June, Benjamin Church, a colonial military leader from Little Compton, convinced the female Sachem, Awashonks and her Sakonnet warriors to make peace with the English. To do so, they had to turn on Philip. Finally, in August, King Philip was killed in present-day Bristol. His death for the most part ended the conflict. The war lingered in the north for a few more years until 1678 when the Treaty of Casco was signed and ended hostilities in Maine. Meanwhile, the white victors sent many Indian captives (even some who had been their allies) to the Caribbean to be enslaved.

Given the dramatic events, it is hard to say why King Philip’s War gets so little attention today. Still, thankfully, its related monuments and historical sites are nestled throughout Rhode Island as silent reminders of the war’s historical significance. Whether you live near the beaches of Narragansett Bay, the woods of Cumberland, or one of Rhode Island’s picturesque port towns, odds are you reside within a 15-minute drive of one of the war’s homages to former battlegrounds.

Those of you from Bristol have probably driven down Metacom Avenue but may not know that the street is named after King Philip—Metacom was his indigenous name. While on Metacom Avenue you can swing by Mount Hope, the location of King Philip’s death in 1676. Also there is the wonderful rock called King Philip’s Seat, said to be the site Philip’s councils. The land is held by Brown University and unfortunately is currently off limits to visitors.

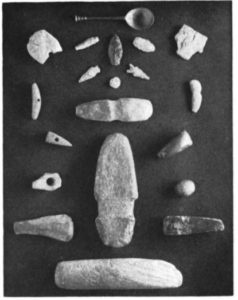

Relics that were found in the vicinity of the Great Swamp Monument location. These relics convinced the Societies of Colonial Wars of Rhode Island and Massachusetts that the battle took place on the Clarke farm.

Canonchet, the Narraganset sachem who destroyed Providence, is commemorated by an impressive modern sculpture at the corner of Ocean Road and Beach Street, in plain view of the Narragansett Towers.

Visiting the following locations allows you to stand where Native Americans and English colonists participated in the war over three hundred years ago. Next time you’re in Providence, stop by the intersection of Canal Street and Smith Street to see where a 71-year-old Roger Williams unsuccessfully pleaded with Canonchet’s men to stop terrorizing the city.[15] From there, the historical sites linked to this conflict span the state. You can head to Smithfield and find the location of the Nipsachuck Swamp Fight. Then, take 295 east to Nine Men’s Misery in Cumberland. When leaving Cumberland, you can follow the Massachusetts state border southeast to Little Compton where you can find Treaty Rock, the site where Benjamin Church convinced Awashonks to make peace with the English.

Every year, history buffs and locals visit the Great Swamp Massacre monument hoping to be at the location of this brutal and monumental battle. Unfortunately, skeptics have argued that the place they are visiting is not the actual site of the battle, that the monument is misplaced. This doubt is tied to a search that began hundreds of years ago.

The search for this historic battleground was by no means an aimless hunt through the aptly named swamp in South County, the Great Swamp. There are dozens of firsthand accounts from those who participated in the battle that have helped to guide the exploration. First, we know that the night before the battle, the Plymouth, Massachusetts, and Connecticut troops spent a frigid night camped out at the Jireh Bull Garrison on Tower Hill in present-day Narragansett. Then, on the morning of December 19, the troops began an arduous march to a swamp seven miles west, led by a captured Narragansett Indian by the name of Peter. When finally arriving, the soldiers referred to the location as a great swamp—today we know it as the Great Swamp Management Area located in South Kingstown. The exact path they took there is unclear but one soldier wrote that they arrived at the swamp and “came up with the enemy” sometime “between 12 and 1.”[16] Although one can assume that the soldiers must have been happy that their hike was completed, they were quickly reminded of the fight that lay ahead of them as they observed the Narragansett fort. Historian George Bodge, in his book, Soldiers of King Philip’s War, quotes a seventeenth century historian who may have spoken with soldiers:

The Fort was raised upon a Kind of Island of five or six acres of rising Land in the midst of a swamp; the sides of it were made of Palisadoes set up right, the which was compassed about with a Hedg of almost a rod Thickness.[17]

After setting their fear aside, the colonists attacked the fort and defeated the Narragansett tribe only after burning everything in sight, including about four hundred innocent civilians and all of their food supplies. Once the fight finished, the soldiers quickly departed the swamp and made the arduous march in deep snow back to Richard Smith’s trading post (now Smith’s Castle) outside Wickford. After putting together all this information, one can deduce that on the afternoon of December 19, 1675, hundreds of Narragansett men, women, and children, were brutally massacred on a raised piece of land located in what we today call the Great Swamp Management Area. This does provide a wonderful starting point, but the Great Swamp Management Area has over 3,000 acres of wetlands filled with numerous patches of raised land, thereby providing several possible locations for the battle. Yet in the late eighteenth century, the president of Yale College visited one of these raised pieces of land and found items that looked to be relics of the Great Swamp Massacre.

On May 28, 1782, the Reverend Ezra Stiles, the former minister of the First Congregational Church in Newport, on his way back to Yale College, decided to swing by a farm owned by the Clarke family in South Kingstown. The farm was about seven miles from Tower Hill and lay on the outskirts of the “Great Swamp.”[18] While on the Clarke farm, Stiles located a “swamp islet” where he found burnt corn remains, two Narragansett burial grounds, and a bullet lodged near the center of a fallen oak tree that was surrounded by one hundred rings that showed the tree’s age. The one hundred rings surrounding the bullet could indicate that it was lodged there around the time of the Great Swamp Massacre.[19] Stiles, convinced that these relics were remnants of the battle, concluded that this “swamp islet” was where the “great slaughter” had occurred about 100 years earlier.[20] These findings remained quiet until about a century later, in 1891, when George Bodge supported the claim that the raised land on the Clarke farm was the site of the battle. Bodge stated:

The place could be easily identified as the battlefield, even if its location were not put beyond question by traditions and also by relics found from time to time upon the place. It is now, as then, an “island of four or five acres” surrounded by swampy land. The island was cleared and plowed about 1775, and at that time many bullets were found deeply bedded in the large trees; quantities of charred corn were plowed up in different places, and it is said that Dutch spoons and Indian arrow-heads, etc., have been found here at different times.[21]

A decade later, historians George Ellis and John Morris further publicized the farm as the location of the Great Swamp Massacre when they stated in their 1906 book King Philip’s War, that “the island upon which the fort was located lies between Usquapaug River and Shickasheen Brook and may be reached by a drive of two and a half miles from Kingston station.”[22] (Kingston Station refers to the train station in West Kingston.)

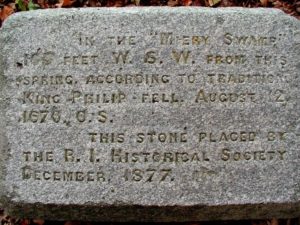

In 1906, confident that the battle had taken place on the Clarke’s Farm, the Societies of Colonial Wars of Rhode Island and Massachusetts erected a monument in South Kingstown to honor those who lost their lives in the Great Swamp Massacre. The monument can be found today by following Route 2 south into South Kingstown, where about a mile south of the Route 138 intersection will be found a dirt road called Great Swamp Monument road. At the end of the road is a 26-foot granite monument that reads:

Attacked within their fort upon this island, the Narragansett Indians made their last stand in King Philip’s War and were crushed by the united forces of the Massachusetts Connecticut and Plymouth Colonies in the “Great Swamp Fight,” Sunday, 19 December, 1675.

Circled around the structure are four boulders, each having one of the names of the colonies that fought against them that day; Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Plymouth.

It is understandable why the Societies of Colonial Wars was convinced that the Clarke farm was the site of the battle—its location and Indian relics found there make for powerful evidence. However, skeptical historians and archeologists would later poke holes in the validity of this evidence while also finding other viable locations for this historic battle. Perhaps the most complete critique comes from historian Eric Shultz in a book he co-authored, King Philip’s War. Shultz masterfully uncovers doubt in the validity of the bullet evidence by referencing Joseph Granger, a student who worked with professional anthropologists from the universities of Rhode Island, Columbia, and Yale to excavate the Great Swamp in 1959. Granger stated, “it is unlikely that such trees [as the two oaks] would have been left standing in a village located specifically for firewood availability as much as for protection.” Shultz adds to Granger’s doubt that there would have been any trees to shoot during the battle as there are no firsthand accounts from soldiers that mention trees being in the fort. Then, when reviewing the other relics found by Stiles in 1782, Shultz deemed them to be somewhat disappointing. He states that “the minister fails to mention the kind of substantial discovery of artifacts and “footprints” that would be left behind by a large, densely populated Narragansett Village.” It is interesting to note that local residents visiting the monument in the 1930s and 1940s also came up empty handed when looking for Indian artifacts. However, those searches were not professionally completed, so it is plausible that they were not equipped with the necessary resources to find the artifacts.

When Joseph Granger dug test pits at the monument in 1959 he found them to be sterile, a term used by archeologists to mean “an excavation layer or deposit in which there are no cultural materials or evidence of human occupation or activity.”[23] Finally, it is important to remember the sheer size of the great swamp that surrounds the monument and the other possible raised lands that could have hosted the battle. Of course, changes in water levels in the swamp over the centuries make the task to find the historic site even more difficult.

One of the raised lands is called Great Neck, which some believe to be the location of the fight. When the site was excavated in 1959 by professional anthropologists, they found “nearly 2,000 pieces of bone, pottery, sea shells, ornaments and stones.” Bullets and burnt corn remnants have also been found along the northern perimeter of the swamp, another possible location of the fort. Then, in 1993 when a more complete archaeological study of the Great Swamp was conducted by members of the Public Archaeology Survey Team, they discovered some of the most powerful evidence to date. Shultz mentions how the “Archeological teams inspected all of the plowed fields within the Great Swamp Wildlife Reservation, nineteen in total” and “one in particular yielded artifacts that might finally indicate the location of the Great Swamp Fight.” Shultz further quotes the findings of the study in great detail:

The exact location of these findings has been kept a secret by the archaeological team for the purpose of preservation, but they have disclosed that it is not at the site of the memorial. Therefore, we now not only know that the evidence used to support the original placement of the monument’s location is currently in question, but that there are perhaps even more viable options for the site of the Great Swamp Massacre. Unfortunately, that is where the work ends and until further effort is put forth, all one can do is question the accuracy of the monument’s placement. It would be foolish not to appreciate the amount of exploration and research done by historians, anthropologists, and archaeologists to find the Great Swamp Massacre’s location. However, it is reasonable for one to expect even more research to be done considering what the monument means to the surviving Narragansett tribe today.

The Great Swamp Massacre marked the violent beginning of the Narragansett tribe’s fight for survival. After being forced into the war by that bloody battle, the Narragansett eventually faced the same devastating fate of racial discrimination, poverty, and slavery as the other Algonquin tribes that fought alongside King Philip. Thankfully, the tribe survives to this day and its members still pay tribute to their ancestors who lost their lives in that great swamp over three hundred years ago. Every December 19th, the Narragansett people can be found at the monument singing songs, storytelling, and partaking in ritualized “wailing.”[25] It is hard not to be moved by the appreciation they have for their ancestors’ sacrifices, but at the same time it is troubling to think that they might be mourning at the inaccurate location. The true location of the fort and battleground must be located not only because of its historical significance but out of respect for the Narraganset tribe members who survive today.

[Banner image: The Great Swam Monument today]

Bibliography:

[1] Eric B. Schultz and Michael J. Tougias, King Philip’s War (Woodstock, Vermont: The Countryman Press), 5. [2] James A. Warren, Gods, War, and Providence: The Epic Struggle of Roger Williams and the Narragansett Indians against the Puritans of New England (New York, New York: Scribner, 2018), 246. [3] Warren, Gods, War, and Providence, 4. [4] Schultz and Tougias, King Philip’s War, 22. [5] Warren, Gods, War, and Providence, 208-209. [6] Schultz and Tougias, King Philip’s War, 42. [7] Warren, Gods, War, and Providence, 226. [8] Schultz and Tougias, King Philip’s War, 248. [9] Ibid., King Philip’s War, 260. [10] Ibid., 263-264. [11] Warren, Gods, War, and Providence, 232. [12] Douglas Edward Leach, Flintlock and Tomahawk: New England in King Philip’s War (1958; reprint, New York; Norton 1966), 166. [13] Schultz and Tougias, King Philip’s War, 61. [14] Ibid., 287. [15] Ibid., 283. [16] George M Bodge, Soldiers in King Philip’s War (Boston, Massachusetts: David Clapp & Son, 1891), 126. [17] Ibid., 137. [18] Franklin Dexter, editor, The Literary Diary of Ezra Stiles, vol. 2 (New York, New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1901), 23. [19] Schultz and Tougias, King Philip’s War, 270. [20] Dexter, ed., The Literary Diary of Ezra Stiles, 23. [21] Bodge, Soldiers in King Philip’s War, 131. [22] George W. Ellis and John E Morris, King Philip’s War (New York, New York: The Grafton Press, 1906), 149. [23] Schultz and Tougias, King Philip’s War, 270-271. [24] Ibid., 271-273. [25] Rick Holmes, “On the Road with Rick Holmes: A massacre hidden in the swamp | Video”. Providence Journal. https://www.providencejournal.com/opinion/20180726/on-road-with-rick-holmes-massacre-hidden-in-swamp–video (September 5, 2020).

Suggested Reading:

- King Philip’s War by Eric B. Shultz and Michael J. Tougias

- If you are interested in visiting the different historical locations tied to King Philip’s War across New England, then this book is a must read. After a quick overview of the war in chapter one, chapter two discusses the different historical events that took place across New England during King Philip’s War, how they affected the war and the community, and directions on how to find them today. This book is what inspired me to write this article.

- God, War, and Providence by James A Warren

- This book does a wonderful job of discussing the relationship between Roger Williams and the Narragansett tribe during the seventeenth century. Warren notes how the book “tells the remarkable and little-known story of the alliance between Williams’ Rhode Island and the Narragansetts, and their joint struggle against Puritan encroachment.”