In Rhode Island history, little is said (or known) about the Native American defenses against the colonial settlers in southern New England. Human beings had learned, early on in their development, that strength lay in numbers and that numbers gathered into a protective enclosure presented a more impressive and safer front against enemies than a single-family unit protecting themselves. A question to Ask Historian on the website reddit.com regarding the first New England native forts was answered thus: “The building of forts by local Coastal Indians, appears to have been well underway before the Europeans arrived. The conclusion from this is that they were built as defensive measures against hostile neighbors.”

With the arrival of early European explorers, the Native Americans were introduced to many new ideas, tools, weapons, construction methods, etc. Much was absorbed and adopted; some showed in the construction of defensive positions, while new weaponry made it possible for the natives to fight on an equal firepower level with the early settlers (as was seen during King Philip’s War.)

Anxious to establish trade with the Native Americans, early explorers may have assisted in the building of “trading posts” both for themselves and for their native allies. Some of these became forts. In Charlestown, Fort Ninigret is a good example. According to Ralph S. Solecki, in his “Indian Forts of the Mid-17th Century in the Southern New England-New York Coastal Area,” Northeast Historical Archaeology, vol. 22, article 5 (1993), the fort comprises a “roughly squared earthworks, each side is not quite 160 feet . . . , with a total-area of about 25,500 square feet . . . or a bit longer than half an acre. There were bastions on three of the corners. There is a continuous low embankment round the perimeter composed of stone rubble, and earth. The embankment, evidently, was thrown up to support palisade walls.” (A bastion is a projecting part—most commonly angular in shape and positioned at the corners of the fort—built at an angle to the line of a wall so as to allow defensive fire in several directions.) The fort was dated between 1620 and 1680.

Fort Ninigret, located in Charlestown, at the end of Fort Neck Road, which extends south from Post Road, near Cross’ Mills. Fort Ninigret occupies a bluff overlooking the northern end of Ninigret Pond. Originally bounded by a stonewall, the site is now outlined by an iron railing. A Niantic site, it was occupied at least twice, once between 700 and 1300 AD and again in the early 1600s.

The fort area became a park in 1883. In 1970, it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Under the direction of Bert Salwen, the area was investigated, leading to the conclusion that it was established primarily as a trading post. The Niantics, allies and relations to the Narragansetts, used the fort possibly as a defense against Pequots and settlers. Since it was built in the military architecture similar to European fort construction, it could possibly have been built as early as 1520 by Portuguese traders or by the Dutch West Indies Company traders in about 1627. Since wampum making equipment was found within the fort area, it may well have been primarily a trading post.

A second fort, Chemunganoc, built in the 1630s near Carolina, may also have been built by Dutch traders for the Niantics, perhaps to offer protection against the Pequot tribe in neighboring southeastern Connecticut. This fort, which may have been located on Shumuncanuc Hill, became a Narragansett stronghold. It was reported to have been a stone and earthworks, 60-yard square fort with no bastions. The hill name means high, enclosed place or place of refuge high up.

Prior to 1637, the Mannissean (or Niantic) people had built a stronghold on a five-acre island at the south shore of Great Salt Pond on Block Island near Indian Head Neck. Fort Island was discovered and attacked by Massachusetts colonial troops under command of John Endicott in 1637. The fort was used by the island’s native inhabitants at least until King Philip’s War (also known as Metacomet’s War or Metacom’s War, June 1675 – August 1676).

Puritan soldiers from Massachusetts, Plymouth and Connecticut shown attacking the Narragansett Fort in the Great Swamp on December 19, 1675 (New York Public Library)

In 1644, as Native Americans in New England found troubles coming amongst themselves and with the colonial settlers, the Shawomet Sachem, Pomham, separated from the Narragansett confederacy and declared support for the Massachusetts Bay Puritans. He asked the United Colonies to build a fort for their mutual protection from the Narragansetts. It has also been said that Pomham built the fort at the instigation of the Massachusetts and Plymouth colony settlers to overawe the Warwick settlers. For some time, there had been much trouble with Massachusetts, which disputed the Shawomet Purchase from the Sachem Miantonomi of the lands in Warwick near Warwick Neck.

Since Pomham also disagreed despite having witnessed the purchase, he may well have been amenable to building the fort. The remains of the earthworks of Pomham’s Fort were still visible in 2021 near the intersection of Paine and Fort Streets on the east side of Warwick Cove. The fort, earthworks with a palisaded strong house, had commanded the entrance to Warwick Cove and was said to have been unapproachable from the rear due to an impenetrable swamp.

On the east side of Narragansett Bay, King Philip’s Fort was built by the sachem, Metacom (King Philip), in the Bristol area, where the main village of the Pokanoket Indians was built. The fort was Metacom’s stronghold, built on or near Mount Hope, a 209-foot hill overlooking Mount Hope Bay. On June 24, 1675, the first battle of King Philip’s War was fought and on August 12, 1676, King Philip was driven out of the fort by English soldiers and their Native allies and perished in the Misery Swamp nearby. This effectively ended King Philip’s War in Rhode Island and the rest of southern New England. It also dispirited his increasingly few Native followers, many of whom abandoned the war effort. Other tribes in northern and western New England continued fighting into 1678.

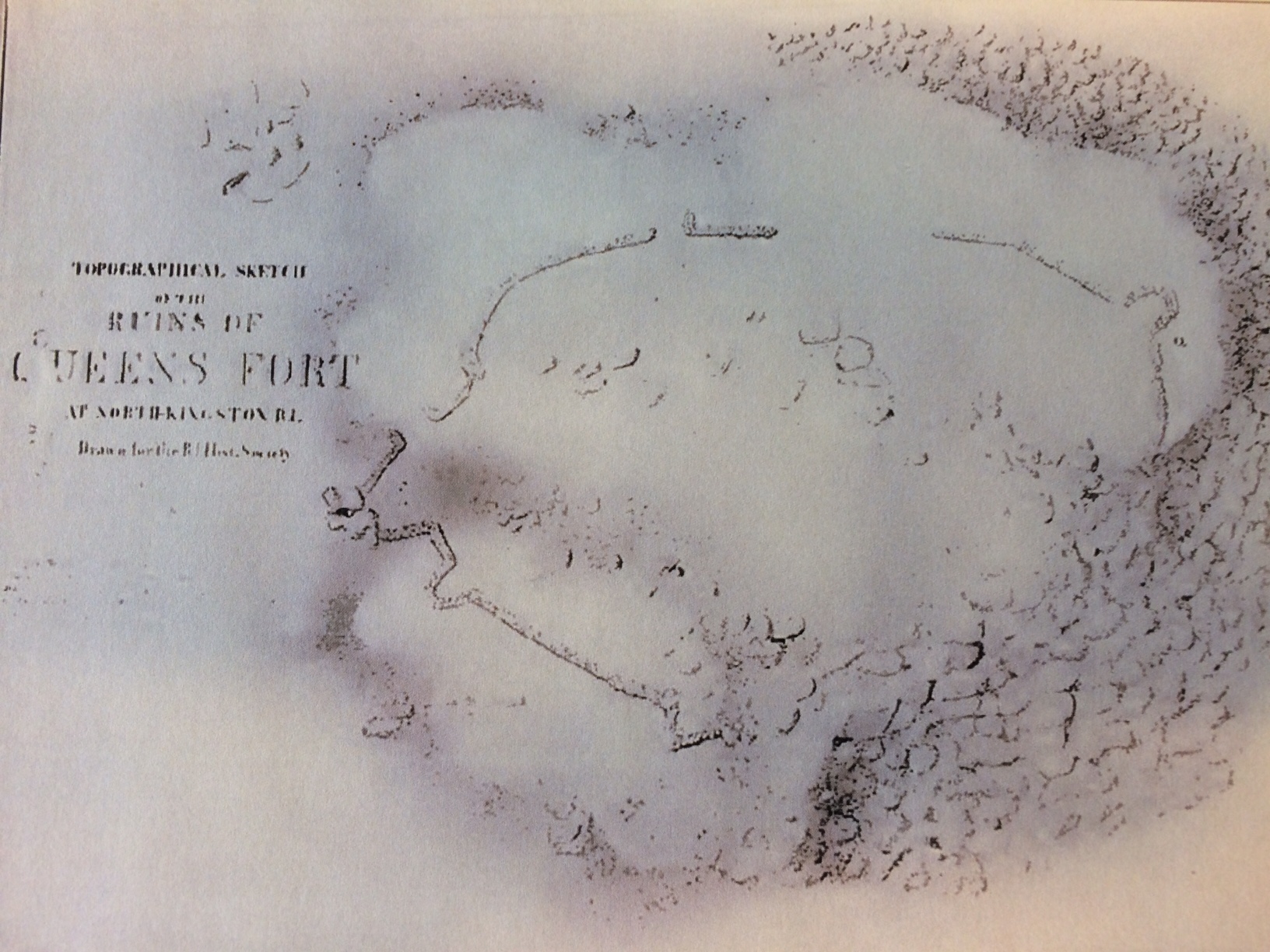

Plan of Queens Fort sketched by Henry B. Hammond, November 1865. The outline of the walls are very noticeable and mostly unbroken (Rhode Island Historical Society Collections, Oct. 1923)

The successful elimination of King Philip was the result of the colonial commander of the troops, Captain Benjamin Church, adopting the tactics of Indian warfare, whereby his men were scattered throughout the woods moving forward, instead of marching in as a block: Captain Church was the head of the first ranger outfit in America, a forerunner of today’s U.S. Army Rangers. Church’s rangers emulated Indian warfare practices, where small, flexible forces used woods and ground for cover as they moved through the area. When Philip fled into the Misery Swamp, Church surrounded it with friendly Indians and his troops spread thinly along the swamp’s edges. King Philip attempted to slip away through the swamp and was shot during his escape.

George Howe, in his “The Tragedy of King Philip and the Destruction of the New England Indians,” American Heritage, vol. 10, no. 1 (Dec. 1958), quotes Benjamin Church as stating that there was an Indian fort on the Tiverton side of the Sakonnet River in 1675. No other record of this is available.

Four forts built by the Native Americans were in existence in the 1670s south of East Greenwich on the west shore of Narragansett Bay. The best known is Canonchet Fort, or the Great Swamp Fort, located in West Kingston on an island in the Great Swamp. The fort included elements of European military fort construction.

Ralph S. Solecki, in his “Indian Forts of the Mid-17th Century,” describes Canonchet Fort as follows: “It was located in a swamp on a piece of firm ground about three or four acres in area. The fort was palisaded but was never quite finished. Inside the perimeter was reported to be a clay wall. The earthworks were built under the direction of ‘Stonewall John,’ an Indian engineer.” The fort included rudimentary blockhouses and flankers at the corners. It was said that there was a forge inside the fort, as Stonewall John was also a blacksmith. Abatis (an obstacle formed of the branches of trees, or whole trees formed in a row with the sharpened tops directed outwards towards the enemy, the row going around the outside of a field fortification) of felled trees with branches forward, some sixteen feet high, backed by a stockade of logs, surrounded the fort. Access was by a single log bridge from a large hummock, the inner end of the log set between a four-foot palisades with loopholes.

The location of the fort is not publicly known. It is not where the Great Swamp Fight monument is located in the Great Swamp in West Kingston off Route 2 (now held by the Narragansett tribe). Reportedly, archeological work is being done on what could be the site of the fort.

Here, on December 19, 1675, the Great Swamp Fight (or Massacre) occurred. Colonial troops from Connecticut and Massachusetts (with perhaps a few from Rhode Island) met at William Smith’s Blockhouse in Wickford; and under the direction of a renegade Indian, marched to the Great Swamp through a snowstorm and attacked Fort Canonchet. The frozen ground facilitated the attackers, who set fire to the structures inside the fort. Stonewall John was among those who escaped, but many occupants—including women, children and the elderly—were killed, primarily from the fire.

Stonewall John had also engineered two other forts: Queen’s Fort in the northeast corner of Exeter against the North Kingstown line and Stony Fort, near the junction of Stony Fort Road on the Exeter-South Kingstown line.

Queen’s Fort was built for Queen Quaiapen, sister of Ninigret, Chief of the Niantics, and wife of the eldest son of Canonicus. She was also known as Queen Magnus, Aaquus, and Matantuck. Near the location of her fort, she reportedly had a large village of about 150 wigwams of Narragansetts.

On December 14, 1675, a few days before the Great Swamp Fight, the troops from Connecticut, Massachusetts and Rhode Island gathered at Richard Smith’s and raided Queen Quaiapen’s village, burning it, taking 40 prisoners, and killing 50. This was recorded on December 15th, by one of the raiders, who stated that Quaiapen and 200 followers escaped to the stone fort nearby.

Carl Pallister stands in the remains of a former bastion at Queen’s Fort, November 25, 2018 (Christian McBurney)

The Queen became restless. She and her people left the fort and traveled north towards North Smithfield to seek refuge in a village in Mattity Swamp. On July 2, 1676, they were attacked in the swamp by a strong party of 300 Connecticut mounted infantry and about 100 Mohegan and Pequot allies, led by Major John Talcott. In the three-hour battle, the Queen’s people suffered 171 killed or captured. In a counter-attack, Narragansett warriors killed 38 of the attackers. The next day, the same Connecticut soldiers and their Mohegan and Pequot allies attacked remaining members of the Narragansetts at Warwick Neck. In the two raids, Quaiapen, Stonewall John, and Potuck, the queen’s chief counselor. The total killings and captures suffered by the victims in the two engagements amounted to 238.

A Boston merchant contemporaneously wrote of the raids:

In June [should be July] Major Talcott slew and took captive four and twenty of the enemy in one week’s time, and also killed the Old Queen of the Narragansett, and an arch villain of their party, who had been with then at the sacking of Providence, famously known by the name of Stonewall or Stone-layer John, for that being an active ingenious fellow. He had learnt the mason’s trade and was of great use to the Indians in building their forts, etc. [This quote is from Merchant of Boston, A New and Further Narrative of the State of New-England Being a Continued Account of the Bloudy Indian-War, from March till August, 1676 (London, 1676), 12-13.]

Queen’s Fort is preserved in a drawing made by Henry B. Hammond in 1865 and added to the collections of the Rhode Island Historical Society in 1923. Today, the site south of Stony Lane between Lantern Lane and Queen’s Fort Brook in North Kingstown and Exeter is owned by the Rhode Island Historical Society. Each year, evidence of the fort is diminished, but some of the stonewall can still be seen.

The fort is unique. It is located on top of a fairly steep hill covered in boulders with a single, winding path to the top. On three sides 200-foot-long walls, broken occasionally by huge piles of boulders, are matched on the fourth side by a massive, jumbled fall of boulders, impossible to scramble over. This boulder field formed the southeast side of the fort. Flankers and a bastion were set into the other walls. (Flankers were projections of the fort used especially to protect a flank or side of the fort). The boulders on the grounds sometimes offered spaces large enough for a man to conceal himself within.

South of Queen’s Fort and north of Canonchet Fort in the Great Swamp were two other small Native American forts. William Davis Miller wrote in his Ancient Paths to Pequot (Providence: Rhode Island Historical Society, 1936):

At a point northeast of Larkin’s Pond this path must have reached “the lower part of the Great Plain,” known even today as the Plains, probably nearby, and passing an Indian fort which was situated east of the Chipuxet on the Ministerial Road just south of the road to West Kingston. It is interesting to conjecture whether or not this was Pesicus Fort mentioned by John Winthrop in his diary:

“(1645, November) 30 we came to the trading house at Coco, Mr. Wilkox house where were 2 English yt traded for ye Dutch Govr, John Piggest & John —–, Mr. Williams man. I stepped over a trap just in ye path right agt Pesicus Fort & I saw it not before I was over it, my man calling to me of it as I stepped over it.”

It would seem quite possible that the fort by the Chipuxet was Pesicus Fort. It was obviously, from Winthrop’s diary, between Warden’s Pond and Richard Smith’s trading house. It would not appear to be Stony Fort, for we have Wait Winthrop’s word that the path by that fort was not known until later and, as the old Queen as a contemporary of Pesicus, it would not apply to Queens Fort, which fort, moreover, would not seem to have been situated on either of the Pequot Paths.

Miller continued:

Now as to this later path “by the stone fort.” The situation of Stone or Stony Fort is indicated on the map and is substantiated by an early deed. It would appear to have been a fort of some importance and from the domestic implements found in its immediate vicinity and from the large quantity of chips found, and to be found, a short distance to the northward, it may be believed to have been the center of an Indian settlement of considerable size.

Blogger JimP, in his blogpost, In Search of Rhode Island’s Lost Stony Fort, writes in his Addendum #2:

I found another reference and more information about the location of Stony Fort.

“Stony Fort is back of Carr’s, east of Arnold Sherman’s. The brook there is called Fort brook. See deed from Anthony Low to Jeffry Champlin. N. Kingstown Records.” (Collections 1835:407)

Collections of the Rhode-Island Historical Society, 1835. Vol. III. Pg. 407. Marshall, Brown and Company.

From Queen’s Fort in the northeast corner of Exeter, it was six miles southward to Stony Fort, near the Exeter–South Kingstown line on Stony Fort Road east of North Road. Pesicus or Indian Fort was built three miles southwest of Stony Fort and three miles east of Canonchet Fort on the east side of the Chipuxet River.

King Philip’s Fort was built by the sachem, Metacom (King Philip), in the Bristol area, where the main village of the Pokanoket Indians was built. This scene shows Puritan soldiers attacking the fort (New York Public Library)

Stony Fort was built to the design of Stonewall John, who was also called John Wallmaker, Stonelayer John, and Nawham. He was a Narragansett mason, blacksmith, and talented tactical designer. There have been theories put forward that he was not a Native American, based on his skill and the military architecture that was evident in both Queen’s Fort and Canonchet Fort construction. However, centuries of Narragansett tribe members have proven their ability to “read the stones” by creating magnificent and practical stone walls and other constructions from the boulders of New England. Whether it was defensive walls for a fort, boundary walls around a property, or a patio around a fire pit, Stonewall John and his descendants today knew how to work with stone!

Notes

For more on Queen’s Fort, see Christian McBurney, Queen’s Fort—Stone Refuge for Quaiapen, 1675-1676, at https://smallstatebighistory.com/queens-fort-stone-refuge-for-quaiapen-1675-1676/

For more on the Battle at Mattity Swamp in North Smithfield and on King Philip’s War, see Dr. Kevin McBride, et al., “The 1676 Battle of Nipsachuck: Identification and Evaluation,” National Park Service American Battlefield Protection Program, Technical Report (April 12, 2013), accessible at https://www.kpwar.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/FINAL-REPORT-Nipsachuck.pdf

For the information on Fort Chemanganuc and Fort Island, see northamericanforts.com/east/ri.html and search for the forts