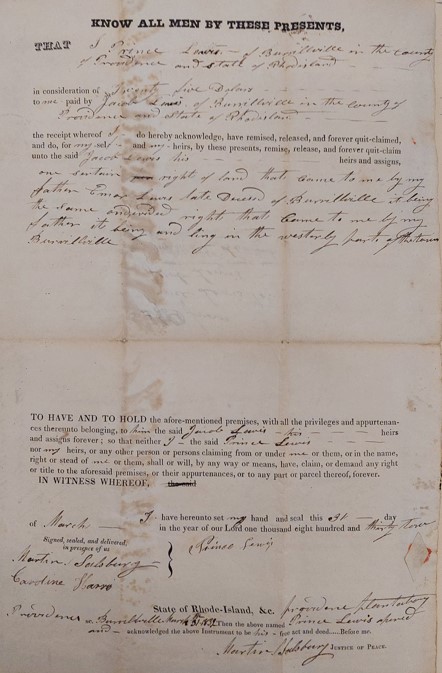

In its September 1840 term, the Providence Supreme Court published an especially peculiar document. The court’s order in Burrillville, a seemingly-simple inheritance dispute, combined handwritten text with printed character in its ruling. While the Judge’s reasoning sprawled from margin to margin in an elaborate cursive hand, Burrillville’s court order featured that handwriting alongside printed text—a nineteenth-century fill-in-the-blank sheet.[1] Thirty-one years earlier, during the Rhode Island General Assembly’s February 1809 term, Bennett Wheeler printed another innovative document. With Oldstyle numerals on each page, new ornamental figures between sections, and diminuendo at the start of each bill, the Wheeler-Jones 1809 report created its own typography.[2] Ever since the inception of the Blaew Press in Providence, local newspapermen were faced with a pressing question: how should they format their documents?[3] Many developed their own typographies, and the Rhode Island courts were no exception.

Order from Rhode Island’s General Court of Trials in 1729. The mixture of handwritten text and printed word defines Burrillville’s typography.

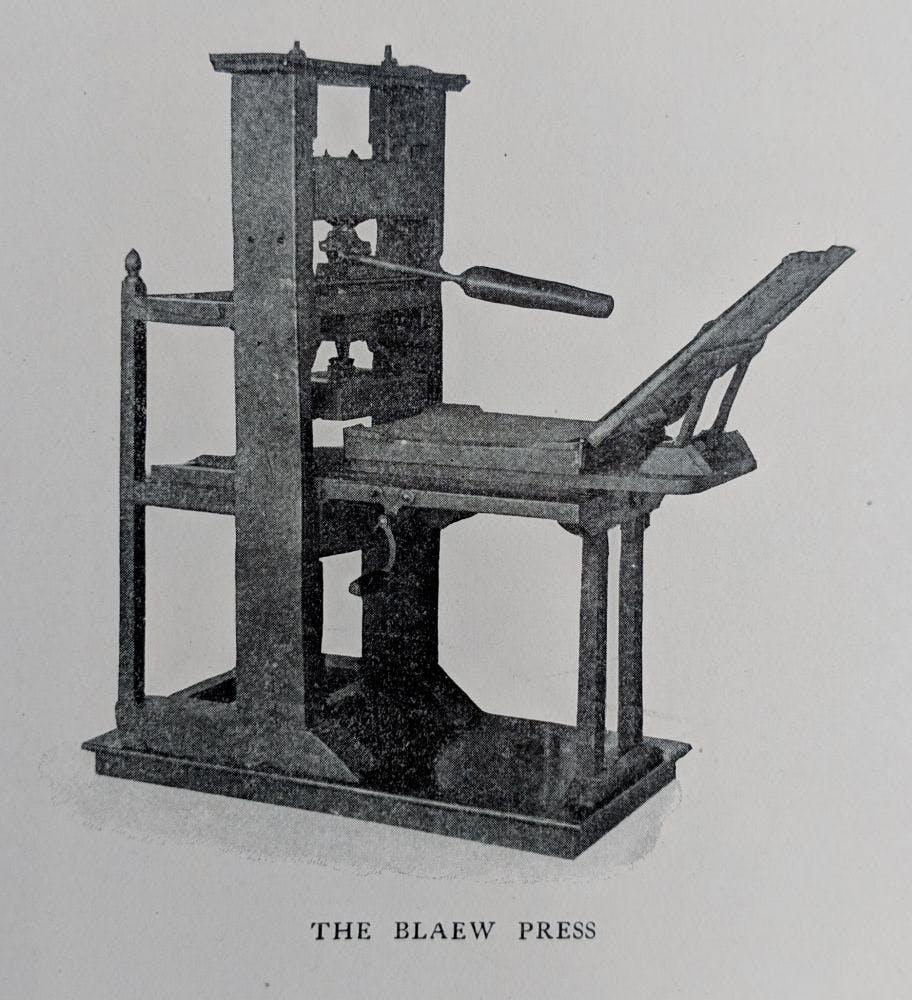

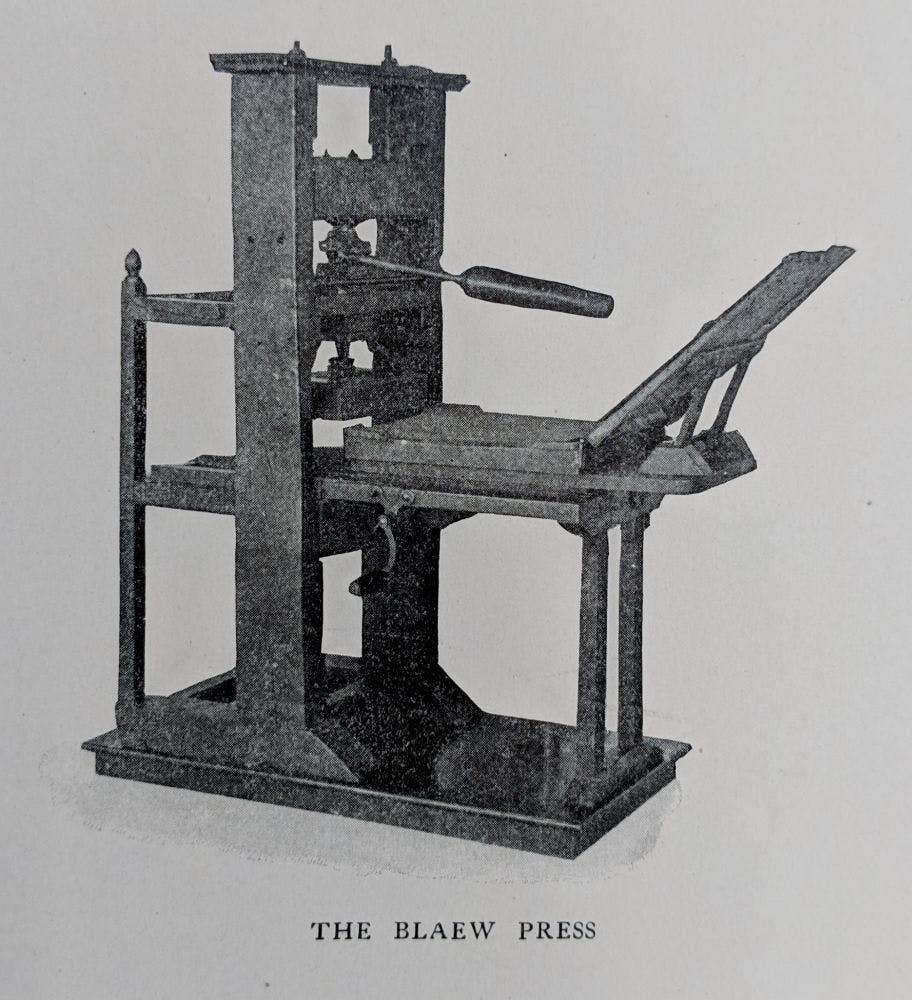

While printers like Oliver Farnsworth and John Carter typeset for the Providence Court of Common Pleas, the state underwent a revolution of printing technology. From 1810 to 1840, Rhode Island transitioned from a mercantile to a manufacturing economy. The state was rapidly industrializing and needed more efficient ways to spread information.[4] Hence, newspapers rose and so did legal texts.[5] Lawyers needed to own collections of previously-decided cases that interpreted newly-enacted statutes and the old common law, under both federal and state law, in order to argue for their clients and to advise them.[6] As Providence’s printing culture matured, so too did its legal field.

Interested in the intersection between Rhode Island’s printers and lawyers, I ask two questions in this article. First, how did the typography of the Rhode Island courts change from 1800 to 1857? Second, who was responsible for those changes? My answer comes in just as many parts. First, Rhode Island’s Court of Common Pleas and Supreme Judicial Courts varied the typographies of their orders, complaints, and judicial opinions based on diminuendo stylization, figure style, and typeface choice. Second, state-contracted printers at the Rhode Island General Assembly like Oliver Farnsworth and Sidney S. Rider were partially responsible for creating that judicial typographic canon.

Most students of the past overlook a document’s formatting. After all, what matters to the historian is what a document says, not what font it employs. Contemporary typographers beg, however, to differ. Robert Bringhurst, in his seminal work on text formatting, asserts that “well-chosen words deserve well-chosen letters.” Typography is an aesthetic medium like any other; a document’s typesetting tells historians how its makers and readers likely saw it.[7] Was the document a warning from the Providence Supreme Court? Or was it an advertisement begging passersby to purchase a new product?

As the Rhode Island courts typeset their documents, printers in Providence developed their own journalistic formatting. Various newspapers, such as the Providence Journal, rose to prominence, but many just as quickly faded into obscurity.[8] State contracts were panacea to Rhode Island printers; securing one ensured job security and local clout.[9] Providence’s newspapermen, when contracted by the General Assembly, joined a new lifestyle where the government became their patrons. The “patronage of the press,” as Culver Smith calls it, guaranteed that the work of local printers was a crucial facet in Providence’s politics.[10] From 1800 to 1857, the printers of Rhode Island were not just formatting the written word; they were packaging and spreading information for their political benefactors.

The Old State House, built in 1741. It originally housed the Rhode Island General Assembly in Newport (John T. Hopf).

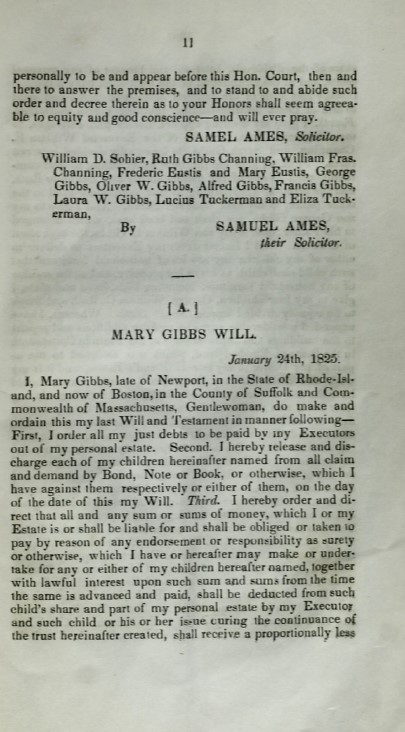

Before 1800, the Rhode Island General Court of Trials developed a unique typography. Judges wrote their opinions by pen in a sprawling cursive hand. Sometimes, as with Burrillville, judges annotated complaint sheets by juxtaposing printed text with handwritten notation.[11] By the end of the eighteenth century, most judges added to Burrillville’s typography. Rather than just writing by hand, they combined print and handwriting.[12] Dozens of cases, from property disputes in Fireson v. Buliod to criminal ones in Mabone, codified a clear judicial style. By the turn of the century, a court document looked a certain way and it exuded a certain formality.[13] Ultimately, the formatting of the eighteenth century was mostly in pen, not print.[14]

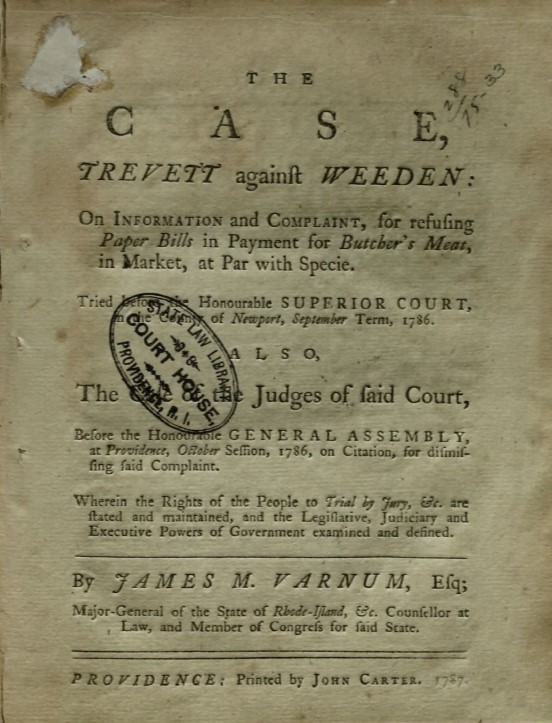

Within that culture, Rhode Island’s Supreme and Common Pleas Courts modified the typographies of their contemporaries, and they did so in three ways. First, court printers shifted between inserting or omitting diminuendo (the transition from larger letters at the start of a section to smaller ones). In the famous Trevett v. Weeden decision, John Carter typeset using enlarged, heavy, non-ornamental letters. The Rhode Island General Assembly, in its 1822 term, typeset with a similar style. For the next twenty years, the no-diminuendo format persisted in most General Assembly documents, up until Crawford Greene’s 1853 printing of Sohier v. Williams.[15] These diminuendo-omitters overlapped between the court and the legislature. In other words, the style of the General Assembly bled into the style of the court and vice versa.

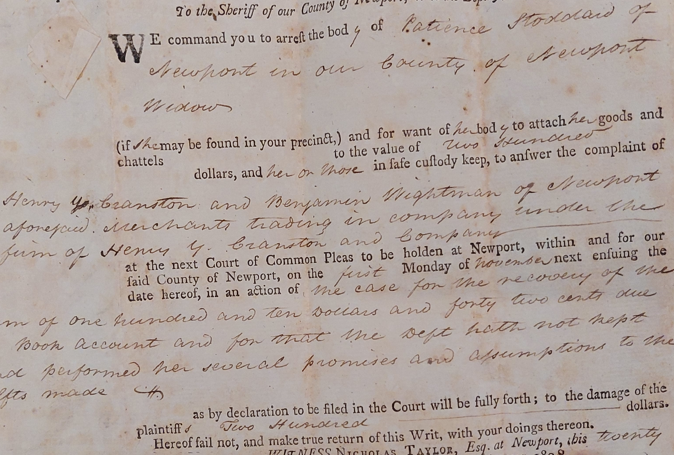

While many typeset without diminuendo, just as many did. In the late eighteenth century, a string of cases immortalized diminuendo in the court’s orders. 1771’s Brenton v. Stoneman, 1774’s Stoneman v. Bannister, and 1775’s Stoneman v. Prior among others did exactly that.[16] With their heightened size and weight, the diminuendo figure demands the attention of the reader. At the turn of the century, diminuendo-printers continued that stylization. 1808’s Cranston v. Stoddard, 1809’s Wyatt v. Standhope, and 1821’s Hill all invert Carter’s non-ornamental typography.[17] Instead, they cherish the loudness and boldness of an enlarged letter.[18]

Second, court printers switched between using lining and Oldstyle figures. For the last decades of the eighteenth century and the first of the nineteenth, most court documents used Oldstyle numerals. Oldstyle numbers are set at varying heights and widths, while lining ones are all the same height.[19] By the 1850s, nearly all court-issued documents featured lining numerals. Phinney v. Phinney, for instance, paginated with standardized numbers.[20] Conversely, the documents of the early 1800s like Wyatt v. Standhope, Cranston v. Stoddard, and the 1802 reports of the Rhode Island General Assembly, all paginate with Oldstyle figures.[21] The choice between different numerals is a deliberate one, and has been ever since the inception of the written number.[22] Perhaps the printers of 1840s Providence used lining figures for heightened legibility. Or perhaps the printers of the early nineteenth century valued the stylization of the Oldstyle numeral more.[23] Despite the intentions of their printers, the Rhode Island courts began to format their numbers differently as the nineteenth century reached its midpoint.[24]

The Blaew Press, a quintessential printing press for Rhode Island’s early newspapermen (New York Historical Society).

Third, the courts’ documents featured new fat-faced and roman typefaces. While fat-faces feature ornate, thin curls attached to heavy cross-sections, romans are smaller and less embellished (think of the Times New Roman typeface). The second typographic camp, the romans, is almost entirely from judicial complaint forms rather than General Assembly reports. Sohier v. Williams prominently sets its text with a thin gothic serif. Trevett v. Weeden too follows Sohier’s style by choosing a roman typeface.[25] The list continues: Cranston v. Stoddard, Stoneman v. Bannister, Flagg v. Franklin, State v. Hopkins, etc.[26] Most importantly, the typefaces of these documents were less embellished than their peers. While the General Assembly Reports of 1822 set themselves with an ornate and loud fat-face, the printers of the courts chose a different route.[27] To them, the rule of law deserved its own style, and that style was swathed in refinement.

The fat-face is as different from the roman as a typeface can be.[28] The romans of Sohier and Cranston are formal. Their letterforms are clear, standardized, and elegant. Fat-faces, on the other hand, are even more formal; they embellish text with a stylized sweep or ornate overture. Starting in its 1822 term, the General Assembly typeset the main body of its reports in a thin fat-face. Until 1827, that trend continued, and it did so (with less prevalence) into the Assembly’s 1850 term.[29] Few judicial opinions or complaints followed, however, that typographic trend.[30] Throughout the period, it seems, one typeface reigned with supremacy while a divergent faction of printers rebelled.[31]

With the first question answered, that brings us historians to the second: who was responsible for these typographic changes? Several were responsible, and by piecing together remnants of their signatures and styles, I inferred that a few prominent printers were the driving forces of Rhode Island’s judicial formatting. The first two are Oliver Farnsworth and Bennett Wheeler. John Eliot Alden’s Rhode Island Imprints, the quintessential text on printing in Rhode Island for the eighteenth century, projects that both men printed for a few years after 1800. Farnsworth moved to Newport in 1798 only to print there until 1805.[32] Since 1779, Wheeler printed in Providence and continued his line of work until 1804.[33] Their tenures as Rhode Island newspapermen coincide with their roles as state printers. The General Assembly Reports from 1799 and 1800 credit Farnsworth for their publication. Farnsworth likely continued printing for the General Assembly until his 1805 termination, as the General Assembly’s typography remained largely unchanged until afterwards.[34] Likewise, Wheeler’s publications for the General Assembly began in the mid-1780s and continued into the first decade of the nineteenth century.[35] The Wheeler typography, with its Oldstyle numerals, diminuendo and roman typefaces, resurfaced outside the General Assembly. So do Farnsworth’s fleur-de-lis ornaments.[36] While the reports of the General Assembly provide the clearest clues as to who developed the formatting of the Rhode Island courts, it is clear that those typographies spread beyond their fields.[37]

Cranston v. Stoddard, a later example of Burrillville’s hybrid typography. It prominently features diminuendo.

Lastly, a cohort of three printers named Brown, Greene, and Rider modified the typesetting of Wheeler and Farnsworth to shape the formatting of the courts. Hugh H. Brown’s formatting of the 1814 through 1817 General Assembly Reports added lining figures to Carter’s unembellished typography.[38] Sidney S. Rider’s printing of State v. Gordon continues that modification by using lining figures and unembellished section breaks.[39] Crawford Greene’s Sohier v. Williams returns to Farnsworth’s original 1799 General Assembly formatting, but adds several more unique ornaments for section breaks.[40] Brown, Greene, and Rider each added his own personal stylizations to the canons of their forebearers.

While few documents survive accrediting court typography to an individual printer, we can surmise that the world of legal printing during the early nineteenth century was in flux. To answer this article’s second question, an enmeshed string of printers developed the courts’ formatting.

One of John Carter’s earliest printed judicial opinions. Trevett v. Weeden (1786) canonized the Carter typography into the courts’ style.

The typesetting of the law oftentimes goes unnoticed, but it should not. Legal books and legal practitioners live in a symbiotic relationship; if books were important to the practice of the law, which they were, then their publication deserves serious attention.[41] The unnamed web of printers living in Rhode Island from 1800 to 1857 shaped the presentation of statutes and judicial opinions alike. In 1847, Joseph K. Angell became Rhode Island’s first court Reporter of Decisions. His duties were to typeset the documents of the Supreme Court and ensure they follow professional conventions.[42] Soon after, the typographers of the court were immortalized in print, unlike their predecessors. Recovering the forgotten history of Oliver Farnsworth and Sidney Rider, for example, reminds historians of the unglamorous underside to the law. Rather than challenging the ideals of this fledgling nation, Rhode Island’s printers shaped the formality and very image of the courts.

Crawford Greene’s 1853 printing of Sohier v. Williams. The document uses a standard roman typeface with no diminuendo.

Bibliography

Adorno, Theodore. “Punctuation Marks.” The Antioch Review 48, no. 3 (1990): 300-05.

Alden, John Eliot. Rhode Island Imprints, 1727-1800. Providence: R.R. Bowker Co., 1949.

Bowen, Henry. “January 1822.” Legislative Report, Providence, 1822.

Bowen, Henry. “January 1842.” Legislative Report, Providence, 1842.

Bowen, Henry. “January 1848.” Legislative Report, Providence, 1848.

Bringhurst, Robert. The Elements of Typographic Style. 2nd edition. Vancouver: Hartley & Marks, 1992.

Brown, Glenn, and Maude Brown. A Directory of Printing, Publishing, Bookselling & Allied Trades in Rhode Island to 1865. New York: New York Public Library, 1958.

Butterick, Matthew. “Alternate Figures.” Practical Typography, accessed 2 May 2022, https://practicaltypography.com/alternate-figures.html.

Catich, Edward M. The Origin of the Serif. Davenport: The Catfish Press, 1968.

Chrisomalis, Stephen. Numerical Notation: A Comparative History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Court of Common Pleas, Newport, November 1808, Cranston and Co. v. Stoddard (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, R.I.).

Court of Common Pleas, Newport, November 1809, Wyatt v. Standhope (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, R.I.).

Court of Common Pleas, Providence, September 1851, State v. Becly (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, R.I.).

Durfee, Thomas. Gleanings from the Judicial History of Rhode Island. Providence: Sidney S. Rider, 1883.

Eddy, Samuel. “February 1799.” Legislative Report, Providence, 1799.

Eddy, Samuel. “February 1809.” Legislative Report, Newport, 1809.

Eddy, Samuel. “February 1815.” Legislative Report, Providence, 1814.

Eddy, Samuel. “February 1817.” Legislative Report, Providence, 1817.

Eddy, Samuel. “June 1813.” Legislative Report, Providence, 1813.

Eddy, Samuel. “March 1809.” Legislative Report, Providence, 1809.

Eddy, Samuel. “October 1814.” Legislative Report, Providence, 1814.

“February 1802.” Legislative Report, Providence, 1802.

“February 1804.” Legislative Report, Newport, 1804.

“February 1805.” Legislative Report, Providence, 1805.

General Court of Trials, F.4, September 1729, Oliver Arnold v. Joseph Bennet (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, R.I.).

General Court of Trials, F.4, September 1729, Stephen Gardner v. Robert Olds (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, R.I.).

General Court of Trials, F.5, September 1729, Major Fairchild v. Benjamin Sawdy (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, R.I.).

General Court of Trials, F.5, September 1729, Joseph Maxon v. Caleb Church (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, R.I.).

General Court of Trials, F.9, September 1729, John Rodman v. William Brightman (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, R.I.).

General Court of Trials, F.11, September 1729, Samuel Rodman v William Clagget (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, R.I.).

Hoeflich, M. H. Legal Publishing in Antebellum America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Inferior Court of Common Pleas, Newport, 1784, Rumreil v. Heffermon (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, R.I.).

Inferior Court of Common Pleas, Newport, May 1750, Mumford v. Jeffries (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, R.I.).

Inferior Court of Common Pleas, Newport, May 1754, Mitchel v. Pinnegar (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, R.I.).

Inferior Court of Common Pleas, Newport, May 1767, Rumreil v. Dennis (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, R.I.).

Inferior Court of Common Pleas, Newport, May 1771, Brenton v. Stoneman (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, R.I.).

Inferior Court of Common Pleas, Newport, May 1786, Flagg v. Franklin (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, R.I.).

Inferior Court of Common Pleas, Newport, November 1743, Pinnegar v. Sanders (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, R.I.).

Inferior Court of Common Pleas, Newport, November 1753, Grant v. Rumneil (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, R.I.).

Inferior Court of Common Pleas, Newport, November 1756, Indictment of Christian Renshon (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, R.I.).

Inferior Court of Common Pleas, Newport, November 1758, Hunt v. Pinnegar (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, R.I.).

Inferior Court of Common Pleas, Newport, November 1774, Stoneman v. Bannister (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, R.I.).

Inferior Court of Common Pleas, Newport, November 1774, Stoneman v. Prior (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, R.I.).

Inferior Court of Common Pleas, Newport, November 1774, Treville et al. v. Bannister (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, R.I.).

“January 1836.” Legislative Report, Providence, 1837.

“January 1843.” Legislative Report, Providence, 1843.

“January 1846.” Legislative Report, Providence, 1846.

“May 1827.” Legislative Report, Providence, 1827.

“May 1850.” Legislative Report, Providence, 1850.

Mendeloff, Nathan H. “A Checklist of Rhode Island Imprints, 1821-1830.” Master’s thesis, Catholic University of America, 1954.

Providence Typographical Union. Printers and Printing In Providence, 1792-1907. Providence: Providence Printing Company, 1907.

Rider, Sidney S. Biographical Memoirs of Three Rhode Island Authors: Joseph K. Angell, Frances H. (Whipple) McDougall, Catharine R. Williams. Providence: Sidney S. Rider, 1880.

Smith, Culver H. The Press, Politics, and Patronage: The American Government’s Use of Newspapers, 1789-1875. Athens, GA: The University of Georgia Press, 1977.

Superior Court of the Judicature, Court of Assize, and General Gaol Delivery, Newport, 1779, Bailey Estate (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, R.I.).

Superior Court of Judicature, Court of Assize, and General Gaol Delivery, Newport, March 1776, Fitzgerald (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, R.I.).

Superior Court of the Judicature, Court of Assize, and General Gaol Delivery, Newport, March 1796, Indictment of Judith Mabone (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, R.I.).

Superior Court of Judicature, Court of Assize, and General Gaol Delivery, Newport, September 1736, Fireson v. Buliod (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, R.I.).

Superior Court of the Judicature, Court of Assize, and General Gaol Delivery, Newport, September 1736, Matheson v. Spencer et al. (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, R.I.).

Superior Court of the Judicature, Court of Assize, and General Gaol Delivery, Newport, September 1736, Snow v. Pain (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, R.I.).

Superior Court of Judicature, Court of Assize, and General Gaol Delivery, Newport, September 1786, Trevett v. Weeden (R.I. State Law Library, Providence, R.I.).

Supreme Judicial Court, Providence, September 1840, Burrillville, Overseers of the Poor (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, R.I.).

Supreme Judicial Court, Providence, 1853, William D. Sohier, Trustee, et. al., Complainants v. John D. Williams, et. al., Respondents (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, R.I.).

Supreme Judicial Court, Providence, March 1821, Thomas Hill v. Scituate Overseers of the Poor (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, R.I.).

Supreme Judicial Court, Providence, March 1840, State v. Hopkins (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, R.I.).

Supreme Court, Providence, March 1844, State v. Gordon and Gordon (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, R.I.).

Supreme Court, Providence, March 1854, State v. Charles Reynolds and Michael McGivern (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, R.I.).

Supreme Court, Providence, September 1854, Dorcas Phinney v. John Phinney (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, R.I.).

Surrency, Erwin C. A History of American Law Publishing. Dobbs Ferry: Oceana Publishing, 1990.

Notes

[1] Supreme Judicial Court, Providence, September 1840, Burrillville, Overseers of the Poor (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, Rhode Island). [2] Samuel Eddy, “February 1809” (Legislative Report, Newport, 1809), 1-38. [3] Providence Typographical Union, Printers and Printing In Providence, 1792-1907 (Providence: Providence Printing Company, 1907), 7. [4] Nathan H. Mendeloff, “A Checklist of Rhode Island Imprints, 1821-1830” (master’s thesis, Catholic University of America, 1954), 5. [5] Thomas Durfee, Gleanings from the Judicial History of Rhode Island (Providence: Sidney S. Rider, 1883), 88. [6] M. H. Hoeflich, Legal Publishing in Antebellum America (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 2. [7] Robert Bringhurst, The Elements of Typographic Style, 2nd ed. (Vancouver: Hartley & Marks, 1992), 18. [8] Mendeloff, “A Checklist,” 16. [9] Ibid., 13. [10] Culver H. Smith, The Press, Politics, and Patronage: The American Government’s Use of Newspapers, 1789-1875 (Athens, GA: The University of Georgia Press, 1977), xi-xii. [11] Burrillville; See also General Court of Trials, F.4, September 1729, Oliver Arnold v. Joseph Bennet (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, Rhode Island). [12] See Inferior Court of Common Pleas, Newport, May 1771, Brenton v. Stoneman (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, Rhode Island). [13] While by no means comprehensive, the following list gives a good representation of the handwritten judicial formatting of the eighteenth-century Rhode Island courts. See Superior Court of the Judicature, Court of Assize, and General Gaol Delivery, Newport, 1779, Bailey Estate (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, Rhode Island); Brenton v. Stoneman; General Court of Trials, F.5, September 1729, Major Fairchild v. Benjamin Sawdy (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, Rhode Island); Superior Court of Judicature, Court of Assize, and General Gaol Delivery, Newport, September 1736, Fireson v. Buliod (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, Rhode Island); Superior Court of Judicature, Court of Assize, and General Gaol Delivery, Newport, March 1776, Fitzgerald (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, Rhode Island); Inferior Court of Common Pleas, Newport, May 1786, Flagg v. Franklin (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, Rhode Island); General Court of Trials, F.4, September 1729, Stephen Gardner v. Robert Olds (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, Rhode Island); Inferior Court of Common Pleas, Newport, November 1753, Grant v. Rumneil (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, Rhode Island); Inferior Court of Common Pleas, Newport, November 1758, Hunt v. Pinnegar (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, Rhode Island); Superior Court of the Judicature, Court of Assize, and General Gaol Delivery, Newport, March 1796, Indictment of Judith Mabone (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, Rhode Island); Superior Court of the Judicature, Court of Assize, and General Gaol Delivery, Newport, September 1736, Matheson v. Spencer et al. (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, Rhode Island); General Court of Trials, F.5, September 1729, Joseph Maxon v. Caleb Church (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, Rhode Island); Inferior Court of Common Pleas, Newport, May 1754, Mitchel v. Pinnegar (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, Rhode Island); Inferior Court of Common Pleas, Newport, May 1750, Mumford v. Jeffries (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, Rhode Island); Inferior Court of Common Pleas, Newport, November 1743, Pinnegar v. Sanders (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, Rhode Island); Inferior Court of Common Pleas, Newport, November 1756, Indictment of Christian Renshon (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, Rhode Island); General Court of Trials, F.9, September 1729, John Rodman v. William Brightman (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, Rhode Island); General Court of Trials, F.11, September 1729, Samuel Rodman v William Clagget (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, Rhode Island); Inferior Court of Common Pleas, New port, May 1767, Rumreil v. Dennis (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, Rhode Island); Inferior Court of Common Pleas, Newport, 1784, Rumreil v. Heffermon (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, Rhode Island); Superior Court of the Judicature, Court of Assize, and General Gaol Delivery, Newport, September 1736, Snow v. Pain (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, Rhode Island); Inferior Court of Common Pleas, Newport, November 1774, Stoneman v. Bannister (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, Rhode Island); Inferior Court of Common Pleas, Newport, November 1774, Stoneman v. Prior (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, Rhode Island); Inferior Court of Common Pleas, Newport, November 1774, Treville et al. v. Bannister (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, Rhode Island). [14] It is a common misconception to state that legal publishing before 1800 was nonexistent since “the amount of legal printing between the establishment of the printing press in Massachusetts in 1636 and 1800 is impressive.” Erwin C. Surrency, A History of American Law Publishing (Dobbs Ferry: Oceana Publishing, 1990), 9. [15] Superior Court of Judicature, Court of Assize, and General Gaol Delivery, Newport, September 1786, Trevett v. Weeden (R.I. State Law Library, Providence, Rhode Island); Henry Bowen, “January 1822” (Legislative Report, Providence, 1822), 1-45; “January 1836” (Legislative Report, Providence, 1837), 1-55; Supreme Judicial Court, Providence, 1853, William D. Sohier, Trustee, et. al., Complainants v. John D. Williams, et. al., Respondents (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, Rhode Island). [16] Brenton v. Stoneman; Stoneman v. Prior; Stoneman v. Bannister; Treville et. al. v. Bannister. [17] Court of Common Pleas, Newport, November 1808, Cranston and Co. v. Stoddard (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, Rhode Island); Supreme Judicial Court, Providence, March 1821, Thomas Hill v. Scituate Overseers of the Poor (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, Rhode Island); Court of Common Pleas, Newport, November 1809, Wyatt v. Standhope (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, Rhode Island). [18] See “February 1804” (Legislative Report, Newport, 1804), 1-20; Samuel Eddy, “March 1809” (Legislative Report, Providence, 1809), 1-28. [19] Matthew Butterick, “Alternate Figures,” Practical Typography, accessed 2 May 2022, https://practicaltypography.com/alternate-figures.html. [20] Supreme Court, Providence, September 1854, Dorcas Phinney v. John Phinney (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, Rhode Island); Supreme Court, Providence, March 1854, State v. Charles Reynolds and Michael McGivern (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, Rhode Island). [21] Wyatt v. Standhope; Cranston v. Stoddard; “February 1802” (Legislative Report, Providence, 1802), 1-11. [22] Stephen Chrisomalis, Numerical Notation: A Comparative History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 1-34. [23] See Theodore Adorno, “Punctuation Marks,” The Antioch Review 48, no. 3 (1990): 300-05. [24] For more examples of lining figures in nineteenth century Rhode Island judicial documents see: Hill; Hunt v. Pinnegar; “May 1827” (Legislative Report, Providence, 1827), 1-8; Samuel Eddy, “October 1814” (Legislative Report, Providence, 1814), 1-50; Samuel Eddy, “February 1815” (Legislative Report, Providence, 1814), 1-30; Samuel Eddy, “February 1817” (Legislative Report, Providence, 1817), 1-40; “January 1822,” 1-10; Court of Common Pleas, Providence, September 1851, State v. Becly (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, Rhode Island). For more examples of Oldstyle figures see Matheson v. Spencer et al.; Cranston v. Stoddard; Stoneman v. Prior; Stoneman v. Bannister; Treville et al. v. Bannister; Wyatt v. Standhope; Samuel Eddy, “February 1799” (Legislative Report, Providence, 1799), 1-21; “February 1802,” 1-15; Samuel Eddy, “June 1813” (Legislative Report, Providence, 1813), 1-35. [25] Trevett v. Weeden; Sohier v. Williams. [26] Cranston v. Stoddard; Inferior Court of Common Pleas, Newport, May 1786, Flagg v. Franklin (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, Rhode Island); Supreme Judicial Court, Providence, March 1840, State v. Hopkins (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, Rhode Island); State v. Reynolds and McGivern; Treville et al. v. Bannister; Stoneman v. Bannister. [27] “January 1822.” [28] See Edward M. Catich, The Origin of the Serif (Davenport: The Catfish Press, 1968), 12-13. [29] “January 1822,” 1-12; “May 1827,” 1-5; Henry Bowen, “January 1842” (Legislative Report, Providence, 1842), 1-25; “January 1843” (Legislative Report, Providence, 1843), 1-27; “January 1846” (Legislative Report, Providence, 1846), 1-17; Henry Bowen, “January 1848” (Legislative Report, Providence, 1848), 1-78; “May 1850” (Legislative Report, Providence, 1850), 1-11. [30] A few did mix different typefaces. See Cranston v. Stoddard; Matheson v. Spencer; “January 1822,” 1-12; Hill; Hunt v. Pinnegar; State v. Reynolds and McGivern. [31] Another interesting dimension where court typographers innovated was in ornament usage. See “January 1802,” 1-20; “February 1799,” 1-10; “February 1809,” 3-12; “October 1814,” 1-15; “February 1815,” 1-20; Sohier v. Williams; Trevett v. Weeden; Brenton v. Stoneman; Hill. [32] John Eliot Alden, Rhode Island Imprints, 1727-1800 (Providence: R.R. Bowker Co., 1949), 625. [33] Alden, Rhode Island Imprints, 631. [34] See “January 1802,” 1-20; “February 1804,” 1-10; “February 1805” (Legislative Report, Providence, 1805), 1-5; “February 1799,” 1-10. [35] Interestingly enough, both Wheeler and Farnsworth were prominent newspapermen of Rhode Island throughout their professional careers. Not only was Farnsworth a bookbinder and book seller in Newport, he also printed papers ranging from the R. I. Republican to the Weekly Companion and Commercial Centinel. In much the same way, Wheeler printed the American Journal and General Advertiser. Glenn Brown and Maude Brown, A Directory of Printing, Publishing, Bookselling & Allied Trades in Rhode Island to 1865 (New York: New York Public Library, 1958), 63, 179; Alden, Rhode Island Imprints, 429. [36] “March 1809,” 1-20; “February 1799,” 1-15; “February 1802,” 1-15. [37] “January 1822,” 1-20; “February 1809,” 3-12; “October 1814,” 1-15; “February 1815,” 1-20; “May 1827,” 1-5. [38] “October 1814,” 1-15; “February 1817,” 1-10. [39] Supreme Court, Providence, March 1844, State v. Gordon and Gordon (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, Rhode Island). [40] Sohier v. Williams. [41] Hoeflich, Legal Publishing, 171. [42] Sidney S. Rider, Biographical Memoirs of Three Rhode Island Authors: Joseph K. Angell, Frances H. (Whipple) McDougall, Catharine R. Williams (Providence: Sidney S. Rider, 1880), 21-22.