In November 1637, the General Court of Massachusetts Bay Colony convicted Anne Hutchinson of heresy and banished her from the colony. More than just a founding mother of Portsmouth, Rhode Island, she can be considered a founding mother of religious tolerance in America.

Illustration of Anne Hutchinson preaching in her house in Massachusetts. No contemporary drawing of her exists (Harper’s Monthly, Feb. 1901)

Born Anne Marbury on July 17, 1591, in Alford, England, Anne Hutchinson was raised with no formal schooling, as was common for the times. However, she was well-educated by her father Francis Marbury, a clergyman, schoolmaster, and Puritan reformer. Her father instilled in her an ability to think critically, an uncommon confidence in her own goodness, a strong religious faith, and a desire to demonstrate that faith to others.

In 1634, Anne, her husband William, and their 11 children crossed the Atlantic to the new colony. A female colonist wrote of the wilderness they found: “the air is sharp, the rocks many, the trees innumerable, the grass little, the winter cold, the summer hot, the gnats in summer biting, the wolves at midnight howling.”

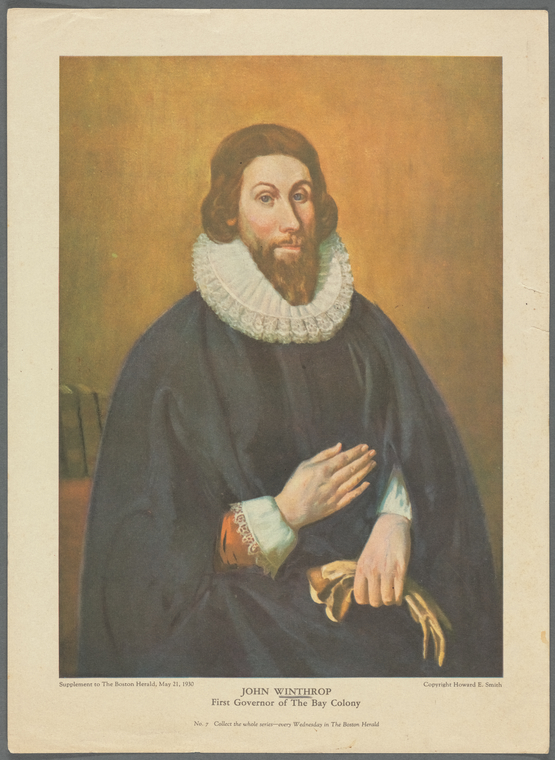

Only four years earlier, a group of Puritans formed the Massachusetts Bay Colony under a royal charter. The Puritans had been harassed and even imprisoned in England for their religious beliefs, specifically the desire to “purify” the Church of England by removing all practices and rituals of the Roman Catholic Church. In the New World, they were free to create a “true” society and state. Theirs would be a “city upon a hill,” as John Winthrop, the first governor, stated in a speech, a near theocracy in which religious and political leadership was closely intertwined.

It is difficult for us today in the increasingly secular Western world to grasp how religion pervaded life for these Puritans in the 1630s. Europe was in the midst of the Thirty Years War, the last of Europe’s religious wars, which saw most of Europe riven by political-religious violence. In daily life the average colonist was constantly concerned with her/his soul and salvation. The devil’s temptations and the potential for sin were ubiquitous.

Winthrop, as the leader and governor of this burgeoning colony, saw himself as the Moses of a new Exodus, establishing a New Jerusalem and initiating essentially a Second Protestant Reformation. To be sure, he would be ever vigilant for anything or anyone who might threaten this vision.

The first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, John Winthrop, took the lead in persecuting Anne Hutchinson (New York Public Library Digital Collections)

It is also difficult today, with the many advances in women’s civil and political rights over the past century, to comprehend how unusual Anne Hutchinson stood in her day. She was well known among the colonists for her services as a competent nurse and midwife. Primed by her father for spiritual instruction, with a gifted mind and strong will, she began a year after her arrival to hold weekly meetings with women in which she discussed the weekly sermons given by the colony’s ministers. Beyond the sermons she also incorporated discussions of scripture and theology. This occurred at a time when women could not vote, teach outside the home, or hold public office.

Initially a handful of women came to the meetings, then scores. Eventually she crossed a red line: she invited men into her circle. Her commentary on the ministers’ sermons became longer and more critical, and she began discussing scripture and theology more generally. She emphasized especially that a soul’s salvation depended on a “covenant of grace” rather than a “covenant of works.” Salvation was a gift and not an objective goal one could win with right actions.

Anne Hutchinson proved to be too great a threat to Winthrop and the other political and religious leaders of the colony. Some viewed her as a witch; others saw her as possessed by the devil. Winthrop called her an “instrument of Satan,” an “American Jezebel,” and suspected her of aiming to establish a “community of women” to nurture “abominable wickedness.”

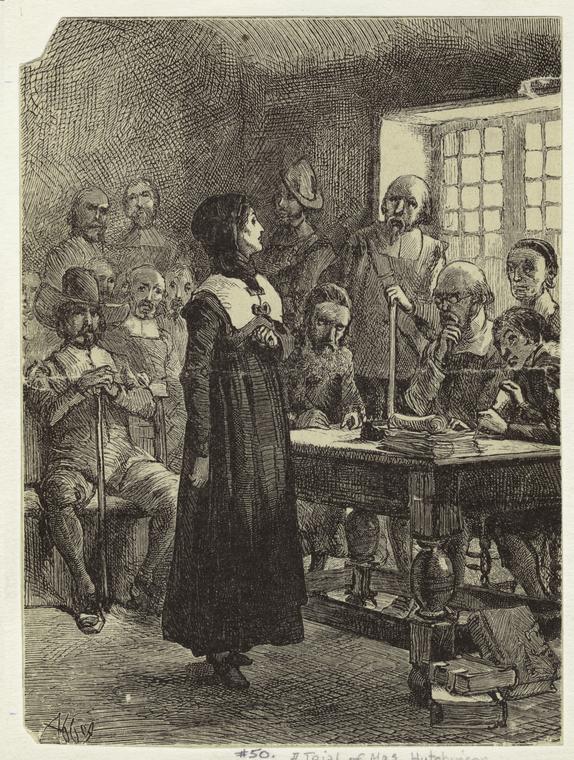

It was a cold November day when she was called before the General Court of Massachusetts, a group of 40 black-clad men at the meeting house in Cambridge, led by Winthrop. Hutchinson was 46 years old, pregnant, of average height, the mother of 12, and grandmother of one. With a white coif covering her head and a white linen smock and neckerchief, the rest of her clothing was black. She was forced to stand while the men sat on benches.

Anne Hutchinson at trial in Massachusetts Bay. Edwin Abbey Austin, artist, circa. 1876-1881 (New York Public Library Digital Collections)

“Anne Hutchinson is present,” announced a male voice. Winthrop began: “Mistress Hutchinson, you are called here as one of those that have troubled the peace of the commonwealth and the churched here.” “You are known to be a woman that hath had a great share in the promoting and divulging of those opinions that are the cause of this trouble ….”

Ending his opening remarks, he stated: “If you be in an erroneous way we may reduce you . . . . If you be obstinate in your course then the court may take such course that you may trouble us no further.”

Hutchinson, probably the first female defendant in the New World, stood steadfast after he finished and replied: “I am called here to answer before you, but I hear no things laid to my charge.”

Anne remained strong and steadfast during the two-day ordeal, fortified by her sure knowledge of divine succor. Before her husband, their eleven children, and she had departed England in 1634, she had had a vision of the adversity to come. She would find herself in the role of Daniel of the Old Testament. Daniel, a Jew, was serving in the administration of the Babylonian empire of King Darius. The other high administrators were jealous of his favored relationship with the king, and so they reported that Daniel had broken the law by praying to his Jewish god, Yahweh, rather than to him and the Babylonian gods. The king was forced to have Daniel thrown into a lions’ den; however, Daniel remained unharmed. King Darius was so stunned that he ordered Daniel released and also converted to Judaism.

“It was revealed to me,” Anne recalled, “that [some] should plot against me, and I should meet with affliction. But the Lord bid me not fear.” God said to her: “I am the same God that delivered Daniel out of the lions’ den. I will also deliver thee.”

Statue of Anne Hutchinson at the Massachusetts State Capitol (New York Public Library Digital Collections)

The General Court combined the powers which our Constitution, 150 years later, divided into three branches: the executive, the legislative, and the judicial. As historian Eve LaPlante points out, “This court’s vast power over the populace limited people’s freedom to a degree that is unimaginable today. People were banned … from wearing any fur, lace, or colorful cloth, and all citizens, whether or not they were church members, were required to attend Sunday services.”

Throughout the two-day trial, the governor and other magistrates questioned her on her authority to conduct religious meetings, called “conventicles,” which had grown in size from a few women to 80 or so women and men. The magistrates and she both rooted their arguments in holy scripture, the ultimate source of knowledge and truth in that day. Religion infused each day of their lives, not just Sundays, and was the prism through which they interpreted reality.

The magistrates questioned her further about her reported criticism of the colony’s ministers, her denial of the importance of performing good works as a sign of salvation, and her claims of divinely-inspired prophecy, a gift which Puritans reserved solely for ministers.

Hutchinson skillfully parried these accusations with quotes from scripture. She argued that testimony given by some magistrates was based on private conversations. Women had no public role in Puritan society. She argued then that she could not be charged and condemned for private opinions and actions.

On the second day of trial, Hutchinson—emboldened by her performance on the first day and convinced of her divine support—could not resist speaking in a manner that would lead to her conviction: she began to preach to the court. In doing so in this public proceeding, she played into the hands of her enemies. Literary scholar Lad Tobin described her speech as a “final act of defiance.”

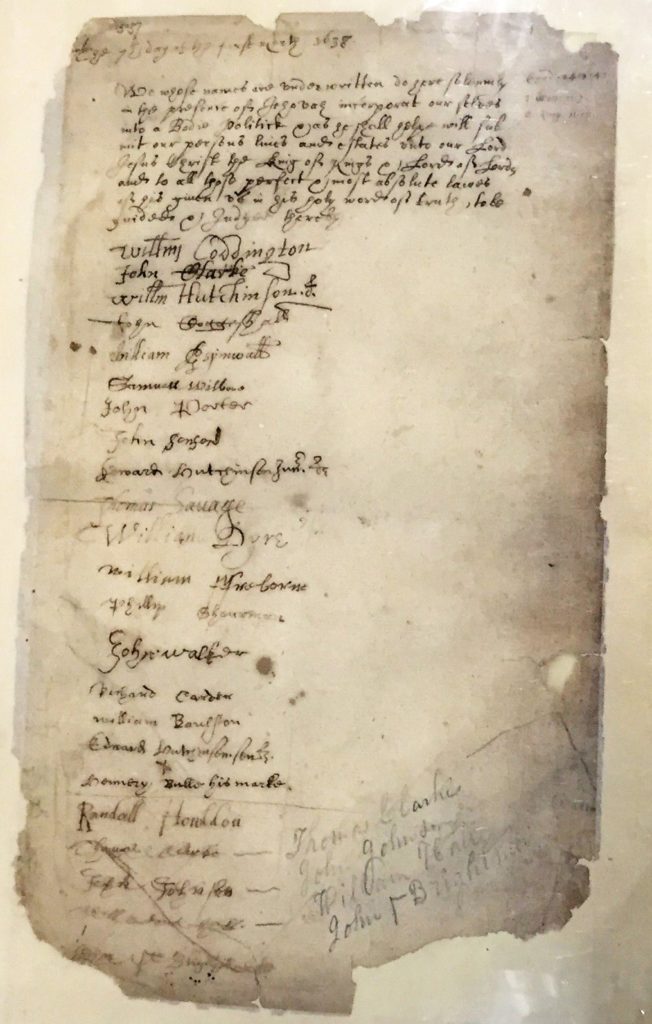

According to the Portsmouth History Center: “The Portsmouth Compact was a document signed on March 7, 1638 that laid the foundation for the establishment of the town of Portsmouth on Aquidneck Island later that spring. It was the first document in history that severed both political and religious ties with mother England.” (Rhode Island State Archives)

After being asked to explain how she knew she had received divine revelation, she answered: “By the voice of his own spirit to my soul.” She claimed: “… the Lord showed me what he would do for me and the rest of his servants!” … “And therefore I desire you ,…, to consider and look what you do. You have power over my body, but the Lord Jesus hath power over my body and soul.” She claimed direct connection with God, and this was heresy.

She then prophesied the doom of the colony. “I know that for this you go about to do to me, God will ruin you and your posterity, and this whole state!”

With such forceful and heretical statements from Hutchinson, Winthrop had what he needed to convict her. Pointing at her, he exclaimed, “This has been the ground of all these tumults and troubles. This is the thing that has been the root of all the mischief.”

In the end, Hutchinson was charged with heresy for her claims of divine revelation and with sedition for her criticisms of the colony’s ministers. Winthrop concluded: “Mistress Hutchinson, the sentence of the court you hear is that you are banished from our jurisdiction as being a woman not fit for our society ….”

Hutchinson was allowed to remain in the colony until the following spring. Until her departure, the “prisoner,” as Governor John Winthrop called her, was required to remain isolated at the home of Joseph Weld in Roxbury. She took her Bible, her Herbal (guide to medicinal plants), and winter clothes. During these winter months, she studied scripture, sang psalms, prayed and meditated, and saw her mid-section grow with her sixteenth pregnancy.

At the same time, husband William and other male followers met secretly and made plans to begin a new settlement. They wanted good soil, access to fresh water and wood, a milder climate, and religious freedom from the Massachusetts colony.

Initially planning on Long Island or New Jersey, they decided to settle on Aquidneck Island, at the urging of Roger Williams, the founder of Providence.

On March 7, 1638, a group of men—eventually 23—signed the Portsmouth Compact, incorporating themselves into a “body politic.” Anne’s husband, William, signed it third, behind William Coddington and John Clarke. With the help of Roger Williams, these men acquired the island from the Narragansett sachems (chieftains) Miantonomo and Canonicus, for a collection of beads, coats, and hoes. They decided to settle on the northeast section of the island, which the Indians called Pocasset. The settlers soon changed the name to Portsmouth, after the English port city from which some had sailed.

The church trial of Anne Hutchinson was held on March 15 and 22, 1638, in the Boston meetinghouse. The church leaders held documents which described her numerous “errors” in belief on such arcane subjects such as the mortality of the soul, the resurrection of the body on the last day, and the necessity of the saved to follow earthly laws.

Sign for Founders’ Brook Park and the Anne Hutchinson Memorial off Boyd’s Lane in Portsmouth (Fred Zilian)

On the first day, a number of church elders attacked her with vengeance. Thomas Shepard asserted that it was “not God’s spirit but her own spirit that hath guided her hitherto—a spirit of delusion and error!” … “For she is of a most dangerous spirit, and likely with her fluent tongue and forwardness in expression to seduce and draw away many….” John Cotton, the religious leader she had followed for over 20 years, gave her the final “admonishment.”

In a signed document on the second day of her trial, she noted her errors repentantly; however, many church elders continued to scold and reproach her. Reverend John Wilson said: “I look at her as a dangerous instrument of the Devil, raised up by Satan amongst us to raise up divisions and contentions, and to take away hearts and affections one from another.” He proceeded to cast her out of the church.

Followed by a number of her supporters, Hutchinson walked to the door, stopped, turned around and faced the elders and magistrates, and said: “The Lord judges not as man judges. Better to be cast out of the church than to deny Christ.”

On April 1, 1638, the banished Hutchinson, with horses, carts, family, and friends, began a six-day walk to Aquidneck Island. She traveled the last leg by boat and arrived at the new settlement in Portsmouth, described by Eve LaPlante as the “windswept marsh, beach, pastureland, and pebbled cove of her new home.”

Regrettably, under threat of Massachusetts asserting its control over Rhode Island, Hutchinson, after her husband’s death in 1641, decided to move to the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam (current day New York City) in 1642. Unfortunately, the Hutchinsons got caught in the middle of a conflict between the Dutch government in New Amsterdam and the local Siwanoy Native Americans. She and most of her family were killed in an attack by some Siwanoy warriors the following year.

Sign at the Anne Hutchinson Mary Dyer Memorial Herb Garden at Founders’ Brook Park in Portsmouth (Fred Zilian)

Today both a river and a parkway in southern New York bear her name. Massachusetts governor John Winthrop had labeled her “this American Jezebel,” yet in 1987 Massachusetts governor Michael Dukakis formally pardoned her.

Founders’ Brook Park and the Anne Hutchinson Memorial are situated off Boyd’s Lane in Portsmouth. There one finds a shaded glade with benches, marble markers with quotes from Hutchinson, the Founders’ Brook with a small waterfall, an herb garden in honor of Anne Hutchinson and Mary Dyer (another female religious martyr from Rhode Island), and a copy of the compact which was the basis of Portsmouth’s government.

[Banner image: Anne Hutchinson at trial in Massachusetts Bay. Edwin Abbey Austin, artist, circa. 1876-1881 (New York Public Library Digital Collections)]

Bibliography

Conley, Patrick T. Rhode Island’s Founders (Charleston, SC: History Press, 2012).

LaPlante, Eve. American Jezebel (NY: Harper Collins, 2004).

Stensrud, Rockwell. Newport: A Lively Experiment, 1639-1969 (London: D Giles, 2015).