In researching my last book entitled Citizen Soldiers, I came upon many references and stories of those American prisoners who suffered terribly in the makeshift jails of urban confinement or in the sugar houses and churches of New York City, and the dreaded prison hulks off Brooklyn and in Charleston Harbor in South Carolina.

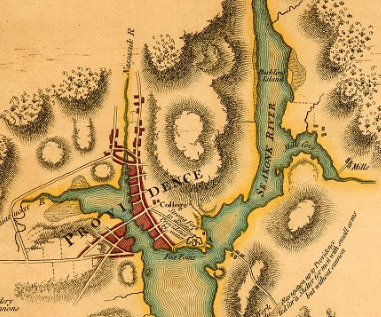

A detail of a map of Narragansett Bay by British cartographer Charles Blaskowitz showing Providence in 1777. The American prison ship was located off Fox Point. (John Carter Brown Library)

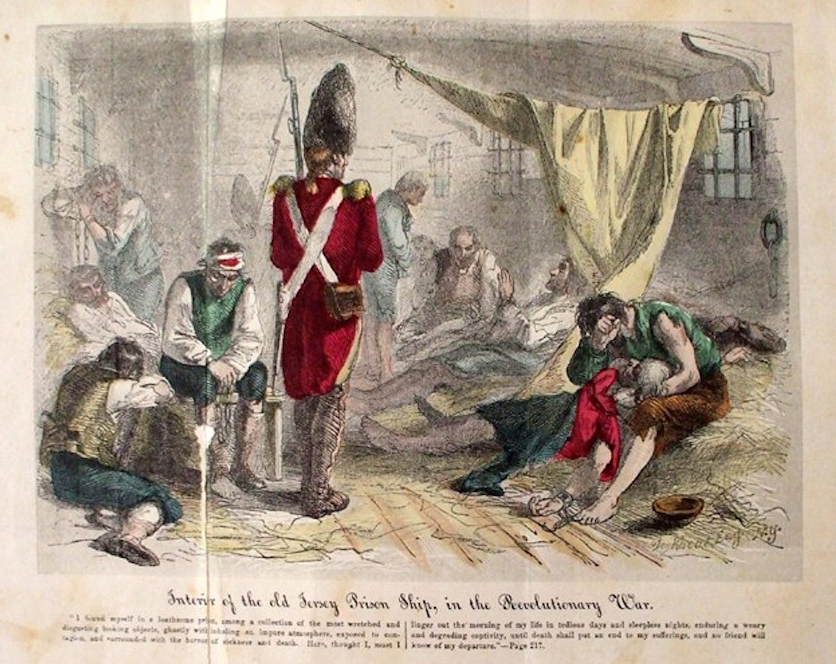

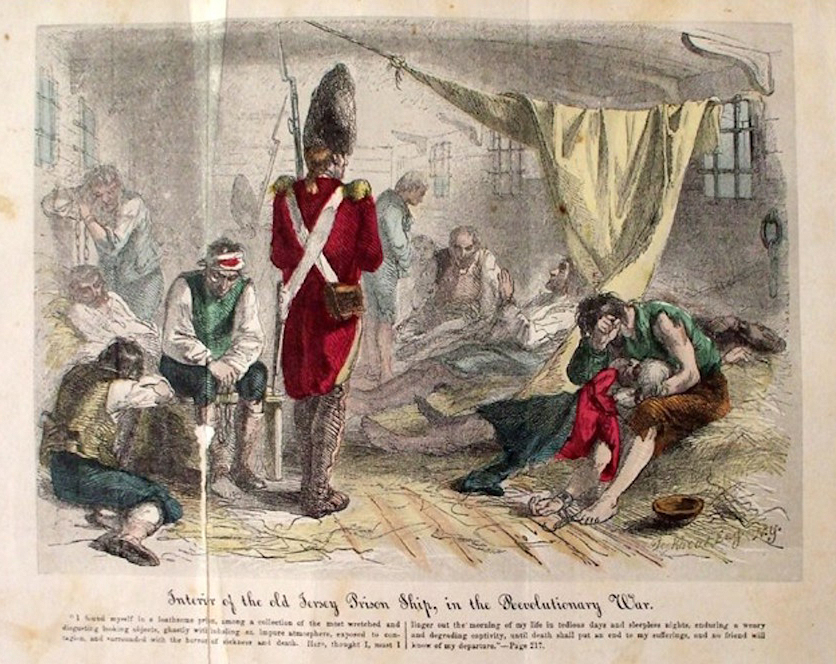

A colorized image of the dreaded British prison ship Jersey that was converted to a prison hulk and left off the Brooklyn coast.

That made me consider the fate of British and Hessian prisoners of war in American prisons. Did they fare just as poorly, or did their captors treat them well as an example in the hope of lessening the suffering of their own countrymen in the enemy’s hands?

Great Britain and the Continental Congress attempted to delineate rules for the confinement and treatment of prisoners of war, but negotiations bogged down with the Crown refusing to see American Patriot captives as anything more than “rebels” engaging in a treasonous war. Attempts soured further with the deaths of American prisoners taken at Bunker Hill.

Washington, by the close of 1776, was eager as well to exchange prisoners, and wrote numerous letters in the weeks that followed the battlefield losses in New York and Long Island. He urged:

governors, committee members and councilmen of the surrounding states”, asking “to have all the Continental Prisoners of War (belonging to the Land Service) in the different Towns in your State, collected and brought together to some convenient place, from whence they may be removed hither, when a Cartel is fully settled.[1]

In the meantime, the states were largely left to their own devices. This was advantageous to those coastal communities that held prisoners who were eager to exchange them for their own imprisoned townsmen.

Washington’s calls to collect enemy prisoners initially were generally ignored. The governments of Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island, having as indicated earlier, been left without a firm agreement from the Continental Congress, had already initiated negotiations and the exchange of prisoners with the British for some time, though there were discrepancies in the lengths of time prisoners were confined. Once the British captured Newport and the rest of Aquidneck Island in December 1776, some American prisoners were brought there and stuffed into small jails or prison ships. In 1777 and 1778, dozens died of disease as a result of unhealthy conditions on board the prison ships and poor food, leaving the prisoners vulnerable to outbreaks of disease.[2]

In the first two years of the Revolutionary War, about one hundred Rhode Islanders spent thirteen months in British confinement amidst the sugar houses and prison ships of New York, after their capture at the failed assault on Quebec in December 1775. By contrast, during this period, the time of confinement of British prisoners in the colonies was considerably less.

Rhode Island has a record of British prisoners seized by the Americans as of the Fall of 1777. It is titled, “A List of the Names, Time of Commitment, and Discharge of the Prisoners of War Committed to Providence Gaol Since the Commencement of the Present War to 5th day of September AD 1777.”[3] This document shows that the jail interred seventy-four prisoners of war over the course of 1776, many of whom were crews of British registered vessels taken by American privateers. Prisoners were kept an average of 2.2 months. The longest-held captive was John Smith and James Wilson, “committed November 16th and discharged March 3rd.” The shortest stints were by a Captain Stanhope of the ship Glasgow and his midshipman, Matthew Scanlon, who were taken prisoner on December 2nd, and released four days later. Their ship, it turned out, was actually detained on its way to New York to transport American prisoners home. Thus, it was probably an error by the American privateer to have seized the ship in the first place.

A British army guard watches over miserable American prisoners on the Jersey. Due to over-crowding, poor food, and mixing healthy prisoners with sick ones, thousands of Americans died on the Jersey (Library of Congress)

Rhode Island had written to Washington before receiving any indication of an exchange. Having seen the notice in the newspaper of Washington’s request to gather prisoners, Deputy Governor William Bradford wrote to the general on September 26, 1776:

Sir: – Having seen in the public papers that Your Excellency and the British admiral have agreed upon an exchange of prisoners in the naval department, I beg leave to apply to you in behalf of a mate of a vessel, and four seamen, all belonging to Warwick, in this state; some of whom are connected with very respectable families. They were all taken in the merchant service, and are prisoners on board one of the ships of war, now in the Sound.

We have a mate of a merchant ship, and four seamen who were taken in a transport, with part of one of the Highland regiments, to give for them. [The Americans in Boston had captured a transport ship filled with Scottish soldiers, after the captain of the vessel did not realize that the British had evacuated Boston.]

I request Your Excellency’s directions, as soon as they may be, whether we shall send the prisoners directly to you, or how I shall proceed to procure the exchange; which will much oblige many worthy people here.[4]

As with other states, Rhode Island was mindful of the tremendous expense that could arise with keeping a multitude of prisoners. As a result, to save money, the General Assembly proved to be quite lenient when petitioned for release by those captured at sea by the state’s sanctioned privateers.

In October 1776, the Assembly reviewed one such petition:

Whereas, James Smith, James Stable and Henry Barnes preferred their petition to this Assembly, setting forth that with the deepest concern they find themselves, after having been captured and brought into this state, unhappily considered as enemies to the rights, liberties, and privileges of America, and detained as prisoners; that having neither in thought, word, or deed, injured the cause of liberty, or joined, adopted or approved of, the present measures, they humbly conceive and pray that the wonted justice, mercy, and humanity of this Assembly will be extended to them… .

The Assembly granted the petitioners the right to purchase a suitable boat for their return to Great Britain, but also voted that:

two of the captains and five mates, who have last arrived within this state, be detained, to exchange for that number of masters and mates belonging to the United States of America, who are now prisoners on board the British ship of war Syren, commanded by Capt. Tobias Furneaux….[5]

The Syren was a British warship that had, after departing Newport in a storm, accidentally run aground on the coast of what is now Narragansett. Rhode Island and Massachusetts militia stationed nearby had forced the surrender of Captain Furneaux and his crew, who were brought to Providence.[6]

Connecticut’s Governor John Trumbull balked at releasing some prisoners, as the state was utilizing some of the more skilled craftsman among the prisoners to bolster fortifications being constructed on Connecticut’s vulnerable southern coastline. Trumbull informed Washington that he had no wish to release the prisoners soon and indicated that some of them might be inclined to stay, rather than return to the drudgery and danger of life in the British army. The governor empathized with “such of the Privates as are Mechanicks & some Others who have a strong inclination to Abide & remain in the Country, must be forced & Obliged to return & be exchanged.”[7]

As for those unskilled prisoners, the state sought to negotiate for exchange and by November had informed neighboring Rhode Island of the opportunity, prompting Rhode Island’s General Assembly to take action on its own:

Whereas, it appears, by express from due authority in New London, in the state of Connecticut, that a flag of truce is there arrived from Lord Howe, for a general exchange of prisoners, confined in the marine department.

And whereas, this Assembly is well informed, that a considerable number of subjects of the American states have been captured by the British navy, as well as those who sailed in American privateers, as in merchantmen; that all are promiscuously confined under decks in large numbers, in a very sickly condition, and under short allowance; therefore for the relief of such,-It is voted and resolved, that the brigantine which the masters and mates of the prizes lately captured and brought into this state, purchased agreeably to an act of this Assembly, together with each and every person who hath a permit to proceed in said brigantine, be detained, and not suffered to depart until further orders from this Assembly, that it may be known, whether if they depart from this port for Great Britain, by permission of the Assembly, a like number will be exchanged for them.

The Assembly also voted “that Thomas Church and Daniel Rodman, Esqs. Be, and they are hereby, appointed to a committee to proceed forthwith to New London, to negotiate with any person or persons, authorized by Lord Howe, an exchange of prisoners….”[8]

Faced with enormous expense in caring for the privateer’s prisoners, and wanting to alleviate the suffering of American prisoners, the Assembly clearly wanted to take advantage of any opportunity for an exchange:

Resolved, that the said committee take an authentic list of their names and stations, and confer with the person or persons authorized by Lord Howe, as aforesaid, whether if said persons be permitted to proceed from this state, as aforesaid, they will be considered as so many prisoners delivered up to Lord Howe; that upon the conditions of exchange being agreed upon, His Honor the Governor be requested to order all the prisoners in this state, that are not under said parole, to be collected together, and sent under proper guard, to the place agreed on, for the exchange, aforesaid; observing first to exchange the prisoners belonging to this state; and then for prisoners belonging to the United States in general….[9]

Prisoner exchanges continued during the war with some interruptions.

Rhode Island, with its active and often successful privateer fleet, had mostly small town jails in which to confine prisoners of war. The jail in Providence at that time, was a narrow, three storied structure that could have held but a dozen prisoners at a time. More was needed. By 1779, the city had installed a prison ship off of Fox Point, where the Seekonk and Providence Rivers flowed into Narraganset Bay.

Some prisoners had opportunity to plead their case, by petitioning the Board of War in those coastal towns that held American prison ships. One such petition came from one Benjamin Clarke who claimed that he, as happened to many, was simply swept up, or in his unfortunate case, shipwrecked into the hands of one warring nation or another. He petitioned the Board of war in Providence on February 3, 1780, explaining his circumstances:

Master of the Schooner Polly who was upset in a violent gale of wind on Thursday August 26, 1779…three men perished. I remained with four of my men on the wreck until the 30th of the month when I was picked up by Capt. Jacobs of this town in a very poor condition…he carried me into (Boston?) from thence sent me to Providence and put me on the prison ship where I now remain a prisoner at present in a very poor condition for the want of clothes and bedding. Therefore I beg the honorable Board of Warr to take my unhappy situation into consideration and Grant me the Liberty to goe to New York. I shall with the greatest honor send a man in my Room which I am shure there is Numbers of Gentlemen suffering in the same condition that I do at present…. So once more I beg of the Honorable Board of Warr to take my unhappy situation into consideration and Grant me my request which shall forever be remembered by your humble and unfortunate petitioner….

Benj. Clark

Prisoner of Warr[10]

That same meeting, another petition involved another casualty of traveling during a global war. The unfortunate prisoner was a Prussian doctor, taken prisoner by the crew of a famous Continental Navy sloop of war, the Ranger, once commanded by Captain John Paul Jones. The doctor writes at length to the Board of War of his circumstances in a most officious manner:

The humble petition of Jacob Heisser, now a prisoner of war, a native of Prussia, and in the service of his Prussian majesty…

Herewith…..that your petitioner was Doctor on board of the ship George, one of the Jamaica fleet taken by the Providence, Ranger and Queen of France, Continental frigates on the 20th of July 1779 and carried into Boston.

That your petitioner have liberty from Capt. Simpson of the Ranger[11], to come to Providence, and take the opportunity which (was) offered at that time, to ship himself on board a Vessel bound to St. Eustice, and from thence to go to Holland on his way to Prussia/having a kind of furlough only for a few months from his King, and was desirous in that time to see the West Indies, therefore entered into the Line in which he was unfortunately taken prisoner.

Upon your petitioner’s arrival here, the Vessel was gone down to Bedford, he was endeavoring to proceed there, but was stopped and confined on board the prison ship, then below Foxes Point for three months, notwithstanding there was an exchange of prisoners took place during that time with Newport, but the British having no doctor to exchange him, would not then be of the number…

Your petitioner upon the evacuation of Rhode Island [the British departed Newport in late October 1779], was transported there, (as he was informed) in order to go to New York in a flag, was put into the Provost [a jail on Marlborough Street in Newport] where he was confined upward of foure weeks, at the expiration of that time, was sent back to Providence….

Your petitioner’s health through the inclemency of the weather and distress for clothing was such as to oblige him to go to the Hospital- and when he became reinstated, lent all the assistance to the facility which he was Master of, and that his Art afforded him for upwards of seven weeks….

Your petitioner in consideration of his long and tedious imprisonment and services, prays their honor of the Gentlemen of the Board of War, will consider the hardships of his case, and permit him to go to New York on Parole, and to send a person of Equal Rank from thence to exchange him, or in failure thereof to return to his former imprisonment….[12]

The following month, however, fifteen prisoners succeeded in escaping from the prison ship in Providence. The Rhode Island Council of War determined that:

Wheras Silas Gardner and others laid before the Council an Account of them charged against the State for their Time and Expense in apprehending Fifteen prisoners who escaped from the Prison Ship at Providence, and securing and delivering them to East Greenwich….

The Council of War agreed for the state to pay “Two hundred and three pounds and two shillings for the use of himself and other Persons who assisted him in said Service.”[13]

As for the prisoners themselves, those who could be removed were quickly dispatched. An order from the Council of War the following day resolved that:

all the prisoners of war in this state, who lately made their escape from the Prison Ship at Providence, be immediately sent to Rutland, and that it be and hereby is recommended to the Deputy Commissioner of Prisoners in this State to send them forward accordingly, and that it be recommended to Colo. Greene to furnish a sufficient Guard for that purpose.

The 1st Rhode Island Regiment of Continentals, commanded by Colonel Christopher Greene and including a number of Black soldiers who gained their freedom by enlisting, marched from its encampment at John Greene’s farm in Coventry to pick up the prisoners in the East Greenwich jail and march them as ordered to the prison camp in Connecticut.

With Newport no longer in British hands, Rhode Island had to deal with British authorities in New York for prisoner exchanges. On May 10, 1780, the Council of War ordered the removal of prisoners from Newport:

Resolved that the sloop Endeavor …be chartered and fitted as a Flag at the Expense of the State to transport a number of prisoners to New York and to bring back from there an equal number of the Subjects of this and the other United States who are now prisoners in New York…

Resolved that it be and hereby recommended to Col. Greene[14] or the Commandant of the Post at Newport for the Time being to deliver to Capt. Thomas Jackson all the naval Prisoners lately arrived at Newport who are fit to be removed; he being appointed by this council to carry them to the sloop Endeavor as a Flag of Truce to New York to be exchanged for an equal number of American Prisoners.”[15]

It was the custom of all sides to permit officers who were prisoners of war the freedom to roam a city during the day, so long as they returned to their assigned quarters at night. This was not always looked favorably upon by the populace. In the case of British officers in Newport, there was probably a legitimate concern that they might assist in a British military assault on Newport. The decision was made to move the officers to an interior rural Rhode Island town. In the summer, the General Assembly decreed on July 21, 1780:

Whereas, it has been represented to this Assembly, that a number of British officers, who were captured by the fleet of His Most Christian Majesty [i.e., the French navy], are now prisoners of war in the town of Newport; and whereas, their being at large in the said town, in the present situation of affairs, may be attended with inconvenience to the public-

It is therefore voted and resolved, that it be recommended to Major General Heath to request Lt. General Rochambeau to cause the said officers to be sent to Cumberland, in the county of Providence, there to remain until exchanged, or until the further order of the said General Rochambeau….”[16]

Other prisoners who were not officers were likely confined to the “new jail” constructed in 1772 on Marlborough Street and still in existence today operating as the Jailhouse Inn. The Rhode Island regiment, as well as two independent companies—the Kentish Guards and Kingston Reds—were stationed on the island and could have been assigned to share in guarding the prisoners when they were not assigned to improving the Butts Hill fort and other fortifications o the island.

In 1781, the Council of War received another petition from the crew and passengers of a Bermuda bound vessel:

Whereas David Clegg, Master, and William Smith, mate of the schooner Flying Fish; and Samuel Spencer and Josiah Hodges (for himself, his wife, and two children), passengers in said schooner preferred a petition, and represented unto this Assembly, that being bound from New York to the island of Bermuda, of which they are all inhabitants, they were taken and brought into this state, and here detained as prisoners of war, at a great expense; and that if they may be permitted to return to the said island, they will engage upon their honors to send back, either from Bermuda or New York, a like number of prisoners of equal rank; and thereupon they prayed this Assembly to permit them, at their sole expense, to hire a small vessel, to be qualified as a flag of truce, to carry them to the said island….[17]

The Council of War granted their petition on June 1, 1781, resolving:

Whereas David Clegg, master, and William Smith, mate of the schooner Flying Fish; and Samuel Spencer and Josiah Hodges(for himself, his wife and two children) passengers in the said schooner, preferred a petition… that being bound from New York to the island of Bermuda, of which they are all inhabitants, they were taken and brought into this state, and being detained as prisoners of war, at a great expense; and that if they may be permitted to return to the said island, they will engage upon their honors to send back, either from Bermuda or New York, a like number of prisoners of equal rank … it is voted and resolved, that the prayer of the said petition be granted; they giving their paroles to the commissioner of prisoners in this state….[18]

Desiring to rid themselves of the costly responsibilities of maintaining such prisoners, Rhode Island sought to discharge them as often as could be expedient to the state.

Sometimes Rhode Island assisted neighboring states in the return of their prisoners arising from prisoner exchanges. In one such instance, the Council of War decreed in early December 1781:

It is voted and resolved, that his Excellency, the Governor, and His Honor the Deputy Governor, be, and they are hereby, severally requested to order the two flags which have lately sailed from Providence, with prisoners from Boston to New York, in order to relieve the prisoners belonging to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, into Taunton River to land them; and that His Excellency the Governor be requested to write immediately to the Governor of Massachusetts informing him that said flags will be sent there….[19]

With the war shifting to the South, the number of prisoners held in the coastal communities of southern New England lessened. When the preliminary agreement for peace was signed in Paris in June of 1782, Rhode Island was already looking ahead to recovery from the war. The members of the corporation of Rhode Island College (now Brown University) petitioned the state in May, “representing that the college edifice has been occupied for many years as an hospital and barrack for the American and French troops, and that great damage hath been done the said building…that such repairs as are absolutely necessary may be made at the expense of the public;…and that it shall not again be appropriated as an hospital or barrack.”[20]

By September 4 and 5 1782, The college corporation had granted degrees to seven students, appointed a committee to “break the seal” that still held the portraits of Great Britain’s King and Queen, and reopened the school library.[21]

[1] Jones, T. Cole, Captives of Liberty: Prisoners of War and the Politics of Vengeance in the American Revolution (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020), p. 101. [2] McBurney, Christian, “British Treatment of Prisoners During the Occupation of Newport, 1776-1779: Disease, Starvation and Death Stalks the Prison Ships,” Newport History, Vol. 79, No. 263 (Fall 2010), pp. 1-41. [3] MSS 9003, Vol. 3, p.19, Rhode Island Historical Society. [4] Bartlett, John R., Records of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Vol. 8 (Cooke, Jackson & Co., 1865), p.14. [5] Ibid., p. 15. [6] See McBurney, Christian, “‘Strange Mismanagement:’ The Capture of the HMS Syren,” in the Online Review of Rhode Island History, at http://smallstatebighistory.com/?s=syren [7] Jones, Captives of Liberty, p. 101. [8] Bartlett, Records of Colonial Rhode Island, Vol. 8, p. 16. [9] Ibid. [10] MSS 9003, Vol. 3, p. 80, Rhode Island Historical Society. [11] Among the many celebrated stories of the Ranger includes the following episode, taken from the website continentalnavy.com:

The ship Ranger again left Portsmouth [New Hampshire] on 18 June 1779 to cruise in company with the Providence and Queen of France. Cruising again off the Newfoundland Banks during mid-July, the little squadron fell in with the Jamaican fleet of about 150 ships undetected in the dense fog of early morning. Masquerading as British vessels, the three American warships sailed amidst the enemy fleet all day dispatching boarding parties manning small boats. Taking eleven prizes while not firing a shot or raising any alarm, the Continental Navy vessels and their prizes slipped away from the fleet under the cover of night. Eight of the prizes were sent into Boston accompanied by the Providence with their aggregate cargo valued over one million dollars. The ship Ranger again returned to her home port at Portsmouth where yet another re-provisioning was done.

[12] MSS 9003, v. 3, p.80, Rhode Island Historical Society. [13] Robertson, John K., Proceedings of the Committee of the RI General Assembly & The Council of War, 1778-1783 (Rhode Island Publications Society, 2019), p. 381. [14] The 1st Rhode Island Regiment of Continentals was stationed on Aquidneck Island at this time, mostly in improving the forts the troops had occupied during the earlier Battle of Rhode Island in August 1778. The improvements were intended to help defend French allies stationed in Newport against a possible British invasion of the island. [15] Robertson, Proceedings, p. 382. [16] Bartlett, Records of the Colony of Rhode Island, Vol. 9, pp. 162-163. [17] Bartlett, Records of the Colony of Rhode Island, Vol. 9, p. 163. [18] Ibid., pp. 381-82. [19] Ibid., p. 495. [20] Ibid., pp. 549-550. [20] Mitchell, Martha, Encyclopedia Brunonia (Brown University, 1993) (University Hall online edition at brown.edu, Courtesy of the Brown University Office of University Communications.)