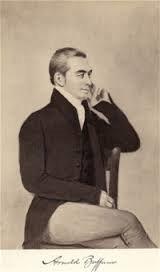

Arnold Buffum, one of Rhode Island’s leading abolitionists, was the second son among the eight children of William Buffum and Lydia Arnold. He was born on December 13, 1782 and raised in a farmhouse near Smithfield’s Union Village, now part of North Smithfield. Arnold’s childhood home, called the William Buffum House for his Quaker father who built it, still stands at 383 Great Road. William Buffum, a member of the Providence Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery, was a strong influence upon his son Arnold.

Despite his rural roots and meager education, Arnold Buffum became an entrepreneur whose main business was the manufacture and sale of hats in Providence. He also patented some inventions pertaining to his trade and raised sheep on his father’s farm as a source of felt for his hats. Business reverses during his career caused his relocation back to the family homestead, and then to Fall River and Philadelphia, and business interests even prompted him to visit Europe twice. He and his wife, the former Rebecca Gould, married in 1803 and became the parents of seven children, all of whom were raised in the Quaker faith. The most notable of these children were their daughter Elizabeth and their son Edward, who became the Paris correspondent of the New York Herald.

Despite his rural roots and meager education, Arnold Buffum became an entrepreneur whose main business was the manufacture and sale of hats in Providence. He also patented some inventions pertaining to his trade and raised sheep on his father’s farm as a source of felt for his hats. Business reverses during his career caused his relocation back to the family homestead, and then to Fall River and Philadelphia, and business interests even prompted him to visit Europe twice. He and his wife, the former Rebecca Gould, married in 1803 and became the parents of seven children, all of whom were raised in the Quaker faith. The most notable of these children were their daughter Elizabeth and their son Edward, who became the Paris correspondent of the New York Herald.

Arnold Buffum’s Quaker beliefs greatly influenced his views on slavery, and soon after William Lloyd Garrison began the publication of the Liberator in 1831, the two joined with other like-minded reformers to establish the New England Anti-Slavery Society in 1832. Garrison became the bold new organization’s secretary-treasurer, while the eloquent Buffum was selected president and the group’s first roving lecturer, a post not conducive to his economic well-being.

For the next decade and a half, Buffum traveled in New England, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Indiana, preaching the gospel of abolitionism to all who would listen, and especially to meetings of the Society of Friends. By the late 1830s, however, he broke with Garrison to support “political abolitionism” through the creation of a third-party dedicated to that goal. He accordingly assisted James G. Birney in founding the Liberty Party in 1840, and supported the Free Soil campaign of 1848. In addition to his passion against slavery, Buffum has been also described as a temperance advocate and a “lover of books.”

In 1843 a fellow passenger on one of Buffum’s European trips described him as “An Old Hickory [i.e., Jacksonian] abolitionist . . . a tall, gray-headed, gold-spectacled patriarch . . . a very sharp old fellow [who] has all his facts ready . . . abuses his country outrageously” as being proslavery, but [who] is still a “genuine democratic American.” In 1854 Buffum died near Perth Amboy, New Jersey in Eagleswood, the utopian community founded by his daughter Rebecca Buffum Spring and her husband, Marcus Spring, but he was eventually returned home to the Smithfield Meeting House for burial beside his wife Rebecca.

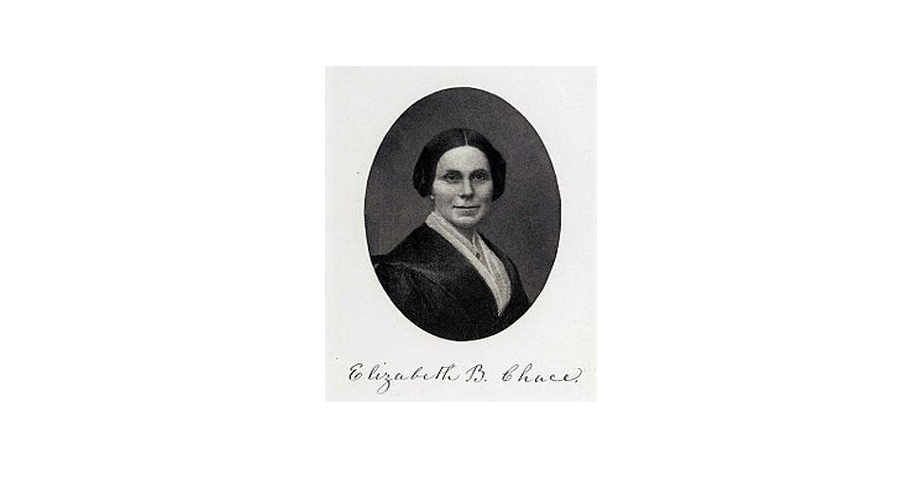

Arnold Buffum’s reform work had a great influence on his second child, Elizabeth, born in Providence on Benefit Street on December 9, 1806. In 1828 she married fellow Quaker abolitionist Samuel Chace, a Fall River textile manufacturer. Elizabeth first became publicly active in the cause of abolition in 1835 when she and her two sisters, Lucy and Rebecca, helped to organize the Fall River Female Anti-Slavery Society, a group that allied with the radical wing of the antislavery movement led by William Lloyd Garrison. The Chaces continued their abolitionist efforts after moving to the Valley Falls section of Cumberland in 1840. Elizabeth organized antislavery meetings and brought illustrious abolitionists to address them including Garrison, Sojourner Truth, Lucy Stone, Abbey Kelley, and Wendell Phillips, and she made her home a station on the Underground Railroad. She detailed these activities in an 1891 book entitled Antislavery Reminiscences.

After the enactment of the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery, Elizabeth Chace joined with Paulina Wright Davis to found the Rhode Island Women’s Suffrage Association in 1868. Chace used her position as president of this organization to address the needs of Rhode Island’s disadvantaged women and children, and she led the successful drive for the creation of the state Home and School for Dependent Children that was established in 1885. In the mid-1860s she became a cofounder of the Free Religious Association and an influential temperance advocate. She also urged reforms to benefit factory workers, especially women and children operatives, as well as prisoners and other deprived groups. She was outspoken, indefatigable, and relentless in advancing the reforms that she espoused, earning for herself the soubriquet “the conscience of Rhode Island.”

After the enactment of the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery, Elizabeth Chace joined with Paulina Wright Davis to found the Rhode Island Women’s Suffrage Association in 1868. Chace used her position as president of this organization to address the needs of Rhode Island’s disadvantaged women and children, and she led the successful drive for the creation of the state Home and School for Dependent Children that was established in 1885. In the mid-1860s she became a cofounder of the Free Religious Association and an influential temperance advocate. She also urged reforms to benefit factory workers, especially women and children operatives, as well as prisoners and other deprived groups. She was outspoken, indefatigable, and relentless in advancing the reforms that she espoused, earning for herself the soubriquet “the conscience of Rhode Island.”

Chace accomplished her noble deeds despite the great burdens and sorrows of motherhood. She and her husband had ten children in the years between 1830 and 1852, the first five of whom died of childhood diseases before the next five were born. Among those who did survive was their son Arnold Buffum Chace, the eleventh chancellor of Brown University and a renowned mathematician and Egyptologist. Even today their progeny are locally prominent in the fields of business and education.

Elizabeth Chace’s long life of reform ended in December 1899, but the memory of her achievements in Rhode Island and elsewhere persists. In 2002 she was selected as the first woman to be memorialized with a statue in the Rhode Island State House, a recognition for local women long overdue.

For further reading:

A full, though dated, account of Chace’s public life, which spanned over sixty years, is Elizabeth Buffum Chace, 1806-1899: Her Life and Its Environment (2 volumes, 1914), written by her daughter Lillie Buffum Chace Wyman and Elizabeth’s grandson Arthur Crawford Wyman. Elizabeth C. Stevens, the editor of Rhode Island History magazine, provides a more recent and scholarly account in Elizabeth Buffum Chace and Lillie Chace Wyman: A Century of Abolitionist, Suffragist, and Workers’ Rights Activism (2003).