This is a most welcome book. Books on Roger Williams can be hard for the average reader to read. In part, this is because sixteenth century English language is so different from modern English. In addition, Roger Williams’s sixteenth century world was vastly different from the modern world we now inhabit and so that can be disorienting as well.

The approach the authors take in this book is effective. They select choice documents, organized mostly by topics, rather than straight chronology. They provide a well-written, informative introduction to each document. Accordingly, it is not always necessary to read each document closely—although doing so often brings surprises.

I also appreciated the way that the authors obtained succinct analysis in emails from various Roger Williams experts, including from noted historian Glenn LaFantasie. They also included many quotes from Chrystal Mars Baker, a Narragansett and Niantic educator who, understandably, has strong views of Williams as well as other White settlers in early Rhode Island.

By employing these methods, I found that I retained more than I usually do with a traditional biography of Williams.

Topics covered include Williams’s banishment to Providence, his establishment of the settlement of Providence, promoting liberty of conscience and separation of church and state, obtaining charters for Rhode Island, navigating relationships with Narragansetts, Wampanoags, and other tribes, and the tragedy of King Phillip’s War.

As with any good historians, a primary goal of the authors is to correct myths. They point out that Williams has a tradition of being seen as a solitary leader and in command of Providence. But the reality is that Williams was in the middle of numerous debates and had to use persuasion to get his way with his independent-minded neighbors.

The authors also point out that Williams is rightfully known for promoting his ideas of liberty of conscience and separation of church and state. Undoubtedly, these were revolutionary ideas at the time—and Williams was well ahead of his time on these issues. But the authors point out that Williams constantly debated Massachusetts ministers, especially the Puritan John Cotton, and that Williams argued vociferously with Quakers.

The authors further point out that Williams is portrayed by modern interpreters as a friend of Native Americans. “What Cheer Netop,” is a well know phrase connected to Williams, implying that Williams and the Narragansetts had a friendly, positive relationship. But the authors persuasively make the case that the truth is more complicated. Yes, Williams spent time with the Narragansetts, enough that he wrote the first ethnographic study of a North American Indian tribe—A Key Into the Language of America, published in 1643. He even argued to John Winthrop that Massachusetts Bay obtained its land from the Massachusetts tribe illegally (whereas he had obtained land from the Narragansetts legally).

On the other hand, after the bloody defeat of the Pequots by Connecticut Puritans in 1637, the authors have a letter from Roger Williams requesting a young Pequot captive to be his servant. (The authors did not indicate any documents supporting that the request was granted.) Even so, Williams argued with Winthrop that captive Pequots should not be enslaved for life and should instead only serve for a term of years, an argument that put Williams in a distinct minority among Whites at the time. Yet Williams, in his letters to Winthrop, called Native Americans “Savages” and “Barbarians.” While these were negative terms, they also indicated that they were not Christians. On the other hand, Williams must have spent hundreds of hours in the homes of Narragansetts and being around them in order to have authored his book on the Narragansett language and their culture and beliefs.

The authors further include a document in their book that makes clear that Williams was organizing a group of Narragansett captives, after the end of King Phillip’s War, to be sold outside of Providence, probably to be enslaved. This made Williams a man of his times, as Whites throughout North America at this time sought to sell Indian captives outside of their jurisdiction as slaves. The authors do concede that it is not known if the captives served as indentured servants or were enslaved for life, or whether they were kept in Rhode Island or transported to say, a Caribbean Island controlled by Great Britain. I suspect it was the latter.

The authors mildly criticized Williams for intensely debating Quaker leaders in Newport. I think the criticism is a bit harsh. As the authors point out, authorities in Massachusetts Bay disliked Quakers so much that they had hung four of them (one was Mary Dyer from Portsmouth). As the authors also point out, Williams never disputed the right of the Quakers to practice their religion in Rhode Island. But ministers from traditional denominations, such as Puritans and Baptists, intensely disagreed with the Society of Friends (Quakers) in their religious practices and interpretations of the Bible. Williams fit that tradition; at least he did not try to execute them. Still, the Quakers made great inroads in Newport and other parts of Rhode Island in the late seventeenth century.

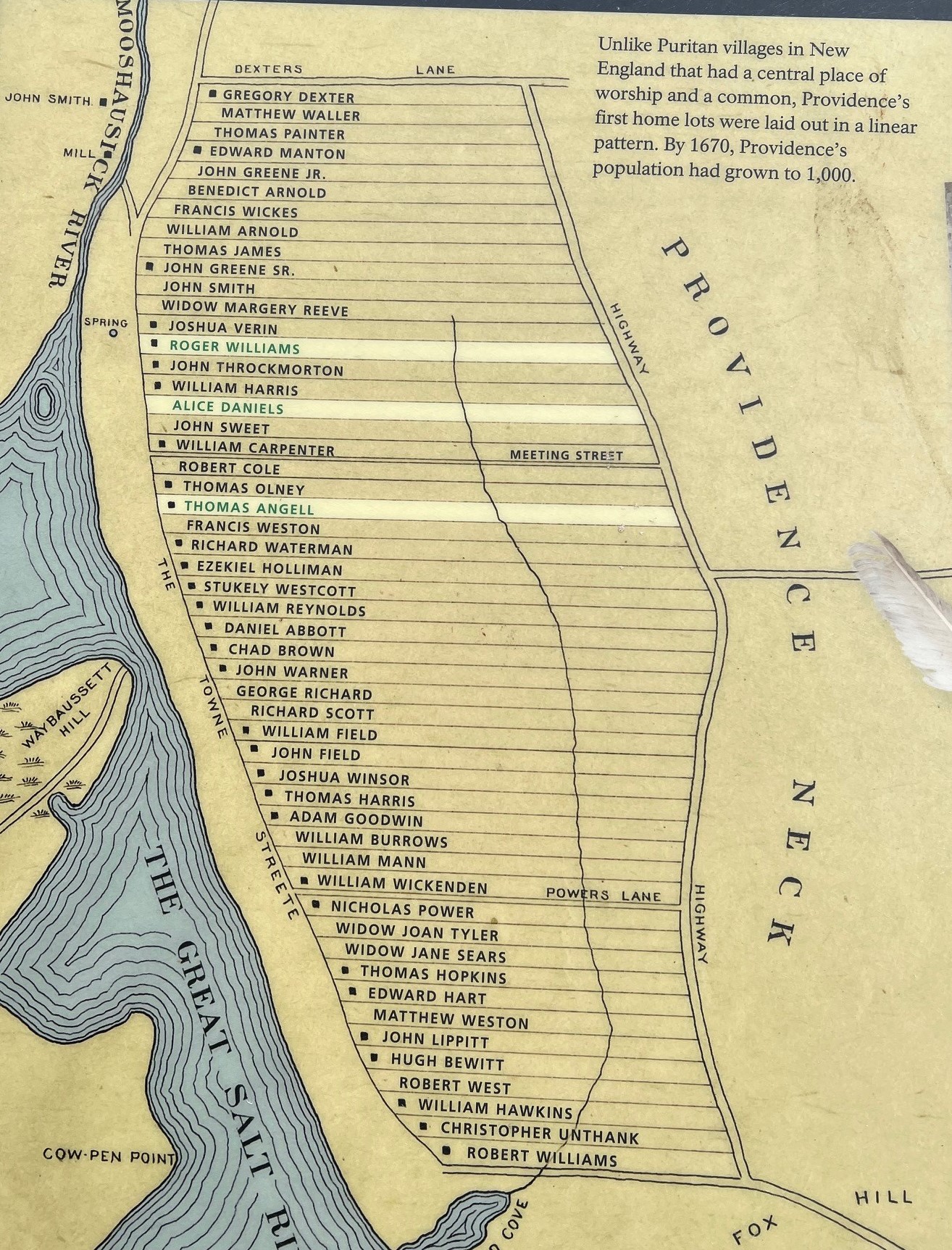

Map showing allotments of land and houses in Providence, circa 1670. The map states that “By 1670, Providence’s population had grown to about 1,000.” (Roger Williams National Memorial, Providence)

One of my favorite Williams letters comes early in the book. As a young religious graduate student on the make, he was searching for a teaching position with a wealthy family in England. The 26-year-old Williams tried to persuade the 77-year-old Lady Barrington that she should hire him quickly so he could provide her with religious instruction as she was so old and her hair so gray that she did not have much time left on earth. Needless to say, Lady Barrington did not hire Williams.

The material on King Phillip’s War in this book is remarkable. For one, while not mentioned by the authors, I believed the tradition that the Narragansetts, in revenge for the surprise attack by Massachusetts, Plymouth and Connecticut soldiers against the Narragansetts at their stronghold in South Kingstown (known as the Great Swamp Massacre), burned the houses at Providence, but did not kill any settlers. The implication was that the Narragansetts liked the White settlers but needed to at least burn buildings to sate the need for revenge. But that is not accurate. When Narragansett warriors burned the houses at Providence, most of the town’s settlers were safe inside a fort. Those who were not, including several women, were killed by the raiders.

I thought the most fascinating letter was by Williams explaining to his brother on Aquidneck Island what happened on that fateful day. Some Narragansett minor sachems invited him outside to discuss the situation, although he was warned not to go near houses where young warriors were doing their violent work. In their introduction to this letter, in part, the authors write compellingly (at page 326):

With the air thick from the smoke of smoldering English homes and farms, Williams and Native men from various tribes confronted each other, both looking for reasons and explanations for the others’ actions. What unfolds is a rare look into the differing perspectives on the war and its meaning at a particular raw moment. The Natives pointed to specific betrayals, including the taking of Native land and joining with Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay against the Narragansett (which Williams denies). Interestingly, both sides claim God was on their side and pointed to evidence for that in recent victories. Williams, clearly exasperated, speaks rather menacingly to the assembled Native soldiers, stating that “God would help us to Consume Them” and that “King Charles would spend Ten Thousands before he would lose this Country.” Williams ends the letter to his brother by instructing colonists in Newport to build forts and hunker down or else they would meet the same fate as Providence.

Reading Roger Williams certainly establishes that Williams, when the chips were down, allied himself with the Whites in Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth, and Connecticut, rather than with the Narragansetts and Niantics with whom he got to know so well. He appeared to be caught in the middle, not wanting the Narragansetts to participate in King Phillip’s War or to be abused by fearful Whites. But the war, which had the highest death rate among Whites of all wars in the United States, forced everyone to pick a side. If Williams had picked the side of the Narragansetts, he might have wound up executed by Whites, as was the White settler from Kingstown, Joshu Teft. If the Native peoples had emerged victorious in King Phillip’s War, what would have been the fates of the White captives? It was an existential conflict for both sides.

Most of the documents written by Roger Williams are letters to John Winthrop and other Massachusetts Bay leaders. Williams was trying to ingratiate himself with them, so that the larger and stronger colony would not gobble up tiny Rhode Island. It would have been amazing to have a transcript of the hundreds of hours of conversations Williams had with Narragansett sachems and other tribal members, but they were not kept (unsurprisingly). We do have Williams’s comment that “It is a strange truth that a man shall generally find more free entertainment and refreshing amongst these Barbarians [i.e., Narragansetts and other Indians], than amongst thousands that call themselves Christians.”

The authors of Reading Roger Williams have impressive backgrounds. Linford D. Fisher is an associate professor of history at Brown University and has written two books, including one on Roger Williams. Sheila M. McIntyre is an associate professor of history at the State University of New York in Potsdam. Julie A. Fisher is a historian and educator, and the author of an excellent, underrated book, Ninigret, Sachem of the Niantics and Narragansetts: Diplomacy, War and the Balance of Power in the Seventeenth-Century New England and Indian Country.

Remarkably, there is another book on Roger Williams focusing on original documents that was recently published. The title of the book is Roger Williams and His World: A History in Documents, by Roger Williams University professor Charlotte Carrington-Farmer and published by the Broadview Press. I have not read this book—yet.