After the French Revolution, while tensions between Great Britain and the new French revolutionary government were growing, the disruption with trade to the West Indies was acute, especially for Rhode Island, whose economy depended on the trade to regain its footing after this country’s own Revolutionary War. When war broke out on the high seas in 1793, tensions between America and France were exacerbated after French privateers took American merchant ships as prizes, while a United States delegation sent to Paris struggled to even get a hearing.[1] The British also treated American merchant ships with disdain, boarding them by force and impressing any British-born man aboard into the Royal Navy.

During these years of turmoil, while some prominent Rhode Island merchants still in the Africa trade turned their attention to the growing market for slaves in Havana, Cuba, others looked toward the U.S. South. Trade with the southern colonies had been productive before the war, but the popular appeal of those liberties stated in the Declaration of Independence, along with a decreased demand in nearby settled areas, led several port cities, especially in the Carolinas, to ban the importation of slaves. The prime port in the region for the slave trade then became Savannah, Georgia, which still allowed the terrible trade.

The reluctance of substantial merchants to trade with the South merely opened the door for others, often with little or no experience, to exploit the slave trade. Such was the case with shipbuilder and ship captain Caleb Eddy of Warren, Rhode Island, who undertook what turned out to be a less than profitable venture from 1795 to 1797. We know what happened because the ship’s log kept by the ship’s mate has survived.

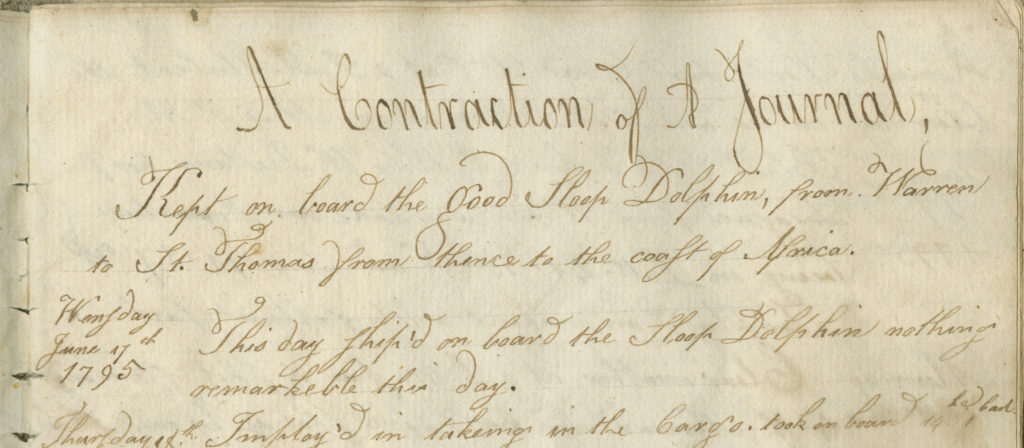

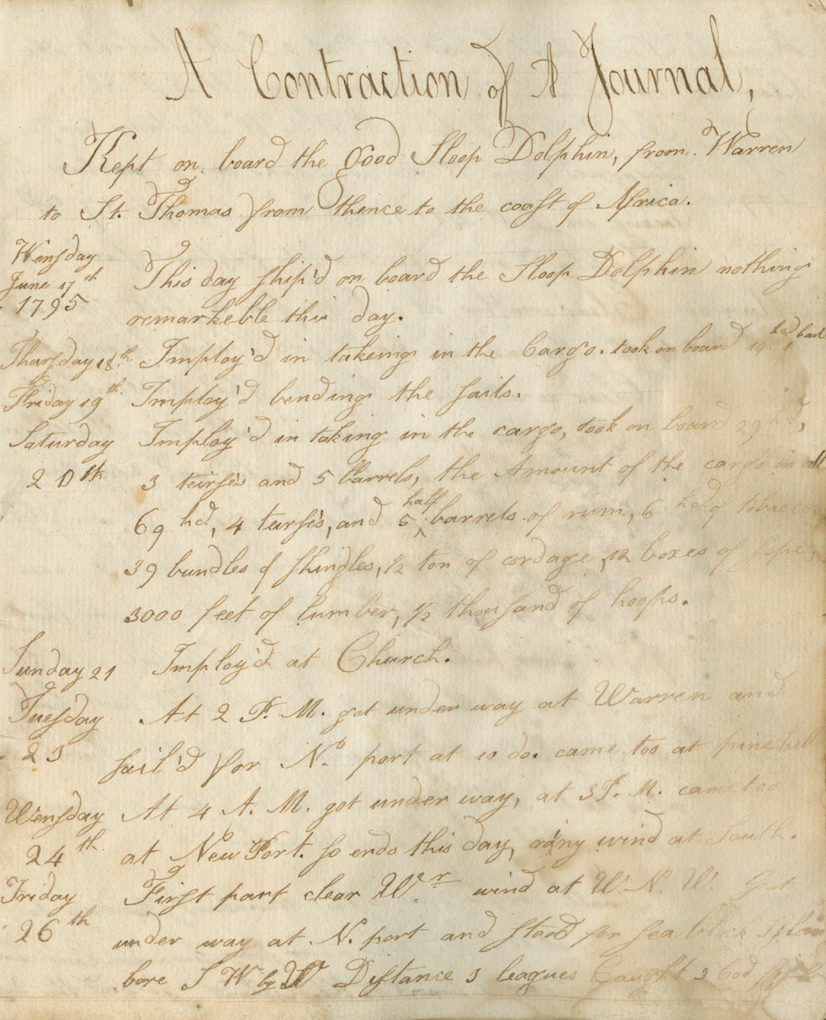

Banner from the cover page of Ship’s Log of the Dolphin, Rising Sun, Fame and William, Warren, R.I., commencing June 17, 1795 (Rhode Island Historical Society)]

The sloop Dolphin left Warren with Captain Eddy and crew on June 21, 1795, sailed the short distance to Newport, and was then bound “to St. Thomas from Hence to the coast of Africa.” On board was placed cargo intended for purchasing slaves, including 6 hogsheads and 5 half barrels of rum, 6 hogshead of tobacco, 39 bundles of shingles, 3,000 feet of lumber and “1/2 thousand of hoops.”

On the 29th, the crew noticed a ship standing “Norward and Eastward,” whose top mast was “Shod.” It was the ship Sally from Baltimore. That afternoon a small boat bearing the Sally’s captain, John Hutchinson, arrived with its occupants asking for a supply of water and food. Captain Eddy complied, giving them a hogshead of water, fifteen gallons of rum, molasses, a bushel of meat, a bucket of bread, and other provisions, for “she was full of famished passengers and short of provisions.”

On July 6, the crew believed they had come within five leagues of Bermuda, a mistaken notion because they were actually off the coast of Puerto Rico. The following day they encountered a brig from Surinam bound for Rhode Island under command of Allen Jacobs.

At 8 a.m. on July 21, the sloop Dolphin arrived at St. Thomas. The crew mailed letters home and went to Blackbeard’s Castle while the ship lay at anchor.

The reason is not clear, but Captain Eddy apparently did not consider his sloop fit for the voyage to the African coast. He apparently sold the Dolphin, perhaps to one Captain Usher with whom he went ashore, and purchased the sloop Rising Sun. On July 26, all hands were sent on board the Rising Sun.

The sloop weighed anchor on August 14, and within a few hours caught sight of a French privateer carrying eighteen cannon, but the Rhode Islanders managed to avoid a confrontation. The next day however, six leagues away from where they had departed, the crew spied “a ship to the westward.” The log reported:

She [the enemy ship] fired 4 shot and we hove to. She stood to the Southard and we sailed away again…we saw the ship under our lee. She fired several shots which whistled among our rigging and ordered us to heave too under her lee. He [the captain of the enemy ship] sent his [small] boat on board for Captain Eddy and his papers. After examining and searching the chests and vessel and threatening to carry him [Captain Eddy] into Martinique they brought him on board and let us go.[2]

The Dolphin continued on its journey to Africa. Light breezes stalled its passage. Some of the crew spied a devilfish but lost half their harpoons trying to haul it in. By the first days of October they were enduring “fresh gales and thick weather,” but by forty-nine days out they spied the Canary Islands. The weather cleared, and on October 15 the crew spotted turtles in the water, lowered a boat and caught two of them, as well as a fish, by the end of the day, “which gave us all a fine dinner.”

Cover page of Ship’s Log of the Dolphin, Rising Sun, Fame and William, Warren, R.I., commencing June 17, 1795 (Rhode Island Historical Society)

Early in the morning of October 21 the crew “saw the land which we supposed to be the Royal [illegible], as at 12 we spoke to a boat from Royal [illegible] bound to the Isles Delos.” Then the crew “at 2 pm hove out the small boat and Capt. Eddy went onboard the schooner for information. At 3 he returned. At 4 saw the Isles Delos as we suppose but the weather makes the land appear odd. There being no people on board the schooner but blacks except one mulatto we liked not there company. At 6 pm we loaded our guns not knowing what they might do . . . .” But no confrontation occurred and the Rising Sun carried on its journey along the West African coast.

On November 4, Captain Eddy made its first purchase of slaves, using goods he had brought from Rhode Island, probably mostly rum and some manufactured products. He placed twenty-one slaves aboard his sloop, along with some water, and wasted little time clearing the decks and leaving by 5 pm. Eddy stopped the following day at “Bonnas Island.” On the 12th, the crew spent the day “imploy’d in landing the cargo and ventures.”

On Friday, November 20, at 2 a.m. the ship’s mate wrote in the ship’s log, “we had a heavy Tornado which caused us to drag our anchor and let go the big one. . . .” The following morning the crew heard news from the ship Liberty “lying at Surilona [Sierra Leone] belonging to Providence. She had made some trade at Goree, and on her passage down from thence the slaves killed Capt. Potter who commanded the ship and cut 1 man very bad, but the rest, with killing one slave drove the rest overboard which was but 6 in number and they took the ship again.” This is all the ship’s mate wrote about this awful struggle between cruelly treated and desperate slaves and the Rhode Island crew that tried to carry them across the Atlantic Ocean.

The Rising Sun put in for repairs and one “Mr. Cleveland” was sent with trade goods to find provisions and acquire slaves along the river Sherborough. The plan was for Cleveland to return to the ship by January—with its cargo of enslaved persons—when the sloop would set sail again.

On December 14, Captain Eddy boarded a brig from New York where he heard news of “the sickness in that Citty which raged to a great height.” The reference was probably to a yellow fever outbreak in the summer in New York City. So far the crew had avoided spending much time on land in Africa and so far had not contracted any serious illnesses. The crew spent Christmas on board the Rising Sun with the gift of a quarter of a goat for their dinner sent from the doctor on land.

On January 14 the Rising Sun was still anchored offshore. Captain Eddy boarded a ship from Providence, “Commanded by Captain Sterry who informed him of some very melancholy deaths” on December 24 of “Capt. Cook arrived here from Rhode Island from which we got information of Captain Edward Gardner at Goree. . . .” The sad news so affected the mate that he put his thoughts into verse:

We in this early youthful age,

Can ease our minds to think of home;

It often makes us for to rage

To think we are obliged to roam.

On February 18, Captain Eddy with four hands took a longboat to search for the long missing Mr. Cleveland along the river Sherborough. Several days later, a Captain Harris arrived from Warren and brought letters from the families of the Rising Sun’s crew. On the 24th, the longboat returned without either Captain Eddy or Mr. Cleveland.

Finally, sickness began to spread among the crew and their human cargo. Two sailors were recorded on March 6 as being “very ill” suffering three days of fever. On Sunday, March 13, Doctor Everson, who had been on the island seven years and expected to set sail as a passenger, died unexpectedly.

Captain Eddy did not return to the ship until April 9, when the crew learned that he had spent ten to twelve days on a “Bento Island” schooner, sick with fever. The captain was better by May, but then the weather turned, and in June, the ship endured another storm, which caused some damage to the sloop. On July 7, the ship’s mate recorded, “Throughout these 24 hours hard gale and raining attended with heavy thunder.” The next day, “The wind still continuing to blow a gale with rain and our vessel’s bottom being so foul that she will not work to windward and the sea running bad we run under the lee of the Island and lay off on until the tide made against us. Then we stood to Northward.”

On July 11, the crew heard of another savage attack on slavers sailing a brig from New York which had left St. Croix. The brig had encountered men in three canoes who wanted to trade for rum. Once on board, the men lashed the captain to a gun and heaved him overboard, and then massacred the remaining crew.

Captain Eddy and his crew brought the Rising Sun ashore for repairs, but found her “very much eaten by the worms.” A makeshift jury on shore (“all the white men on the island”) condemned the ship as being “unfit for Sea.” This was a disaster for the Rhode Islanders. They would have to find another way to return home.

Captain Eddy had the “small” (meaning younger) slaves placed on shore. Two adult slaves brought ashore resisted, and as a result were severely whipped. Two crew members went aboard a “Seralon” (Sierra Leone) sloop and set out with that vessel.

The next morning Captain Eddy and the remaining crew members went on the sloop Fame and “agreed to work our passage to Boston.” It appears Captain Eddy brought on board the Fame the slaves he had previously purchased. The sloop made its way to Bence Island, and then to Sierra Leone where the crew picked up water and provisions before departing for New England on September 30.

A strong wind kept the Fame leeward off the Cape and prevented her from getting away. By mid-December the sloop had made some headway but then encountered “Almost a continual gale of wind from SW to NW which has obliged us to lay too the greatest part of the week.” By Christmas the weather had turned, and the joint crew found themselves “not far from Bermudas making the rest of our way to Charleston” in South Carolina. On the evening of January 13 the crew spotted the Charleston lighthouse and weighed anchor. On January 16 the mate recorded that “at 4pm arrived in the town after a passage of 11 weeks from Seraleon off the Coast of Africa.”[4]

Eddy delivered the papers of the Rising Sun to the Harbor Master and caught a coastal sloop back to Newport, Rhode Island. The mate who kept the log, and the rest of the crew of the former Dolphin, Rising Sun, and Fame, signed aboard the schooner William, bound for Boston. The 114 slaves on board the Fame were also brought to the attention of the Harbor Master. Presumably, they were eventually carried to Savannah or Havana and sold at a local slave market.

In January 1797 Zachary Macaulay, governor of the new British colony of freed slaves at Sierra Leone, wrote in his diary the story of Caleb Eddy and his ship. His summary shows how easily an amateur such as Eddy could get into the slave trade and what dangers an amateur like Eddy faced:

Capt. Eddy commanded a Brig in which was embarked the united fortunes of his Father, his Uncle, and himself. He had never before been to the Coast of Africa, but hearing the slave trade was gainful they resolved to risk in it the fruits of many a year of hard & honest Industry & the hopes of two large families of Children. They made no doubt of doubling their Capital in one voyage. In this hope Eddy came on the Coast 18 months ago, Cleveland & [an English trader] took his Cargo at a rate which was likely to verify his most sanguine expectations. He was to receive so many prime Slaves in three weeks. Cleveland left him at the Bananas [i.e. small islands, off Sierra Leone] & took the goods in his craft into the Sherbro whence he was shortly to remit the Slaves. Month after month however has passed & no Slave has been yet received by Eddy. Cleveland continues in the mean time in the River & trades with the Ships at Cape Mount careless of his promises. The worm has taken possession of the American Brig & it is now condemned. The Crew have perished, at least many of them thro’ want & sickness & the Captain is now seeking a passage back to his friends after having lost almost every farthing of their property & his own. The only thoughts he seems to entertain are those of revenge. “He will make interest in Providence (his town) for a ship he will come out & seize every man woman and child on the Bananas till he has paid himself,” and I make no doubt he will do so.[5]

Eddy and the rest of his crew had been double-crossed by Cleveland. Eddy, despite his bluster, did not return to the Africa coast to seek his revenge.

Understandably, Eddy never again captained a ship to the West Indies, though he likely invested in some voyages. He continued as a “merchant” in Warren, expanding his business interests with the purchase of a lot in Hartford, Connecticut in 1811, in partnership with fellow slaver and merchant Ebenezer Cole.

The “Capt. Potter” the ship’s mate wrote of in the log was another newcomer to the trade. Abijah Potter, the son of Job Potter, a farmer in Gloucester, Rhode Island. He was forty-three years old when twenty-five year old Ammasa Smith of Newport partnered with him in the slave venture.

Captain Potter sailed the Liberty from Providence and reached the African Coast, but was killed during the aforementioned slave uprising, which occurred between Goree Island and Sierra Leone. Potter left a wife and three children back in Gloucester.[6] Amassa Smith remained in Newport to become one of the most affluent and influential financiers in the city.

[Banner Image: Banner from the cover page of Ship’s Log of the Dolphin, Rising Sun, Fame and William, Warren, R.I., commencing June 17, 1795 (Rhode Island Historical Society)]

Notes

[1] Gordon Wood, Empire of Liberty (New York, Oxford University Press 2009), 194. [2] Ship’s log of the Dolphin, Rising Sun, Fame, and William, Warren, R.I., June 17, 1795, MSS 828, Box 12, folder 2, Rhode Island Historical Society. [3] Ibid. [4] Ibid. [5] Quoted in Alexander Boyd Hawes, Off Soundings, Aspects of the Maritime History of Rhode Island (Chevy Chase, MD: Posterity Press, 1999), 144 (citing Journal of Zachary Macaulay, Jan. 17, 1797, Huntington Library). [6] See www.ancestry.com/genealogy/records/abijah-potter_76174755