Providence was founded in 1636 by Roger Williams, and in 1643 Williams obtained a patent from the British crown giving powers of self-government to the towns of Providence, Portsmouth, and Newport. By 1647 Warwick was added and the government was organized at Newport. In 1663 King Charles II granted a charter to John Clarke creating the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, setting boundaries and creating a government document by which the colony was to be governed until 1843 when the first written constitution was established. Initially, freemen were required to travel to Newport, the capitol, to cast their votes for general officers. At that time voting was either by voice vote or paper ballot upon which the names of the preferred candidates were handwritten. Because traveling to Newport created hardships, especially during sowing and harvest times, a system of proxy voting was created. Each April freemen were allowed to cast their votes at town meetings; the votes were sealed, packaged, and taken to the capitol in Newport and counted on Election Day in May; those candidates with a majority of the vote were declared elected to office.

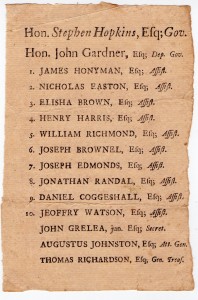

Between 1758 and 1767 Stephen Hopkins of Providence and Samuel Ward of Westerly engaged in bitter elections for governor. This prox dates to ca. 1758 (Collection of Daniel C. Schofield)

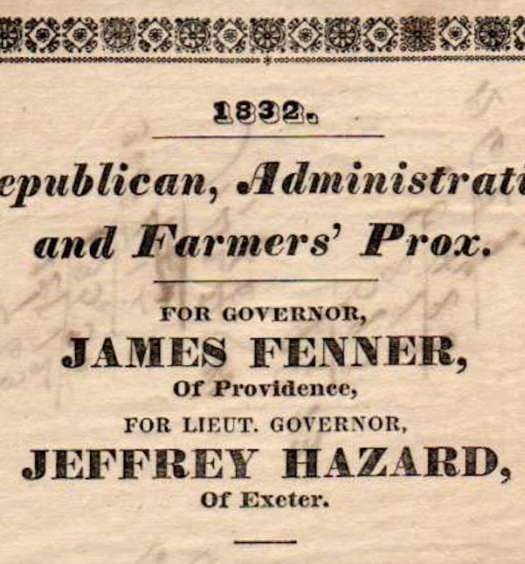

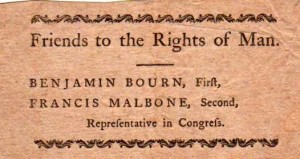

It is believed that Rhode Island was the first colony to have its voters use printed ballots, known as a prox. The earliest surviving Rhode Island printed prox is from 1743/1744, a copy of which is located at the Rhode Island Historical Society. [1] John Russell Bartlett in his Dictionary of Americanisms noted “The use of these words [prox or proxy] is confined to the State of Rhode Island. Prox means the ticket or list of candidates at elections presented to the people for their votes.” [2] Those ballots or proxies contained a list of candidates for Governor, Lieutenant Governor, ten assistants (upper house of the Assembly), Secretary, Attorney General, and Treasurer. The freemen were allowed to cross out a candidate’s name and write in a substitute. Starting in the Revolutionary period, proxies often contained slogans printed at the top, for example, “Liberty, Property & No Stamps” and “LANDHOLDERS! Beware; be firm and persevere: For united we stand, divided we fall!” The Rhode Island lower house of the legislature was elected semiannually in April and August from the various towns.

A few years after the printing of the first prox, political factions developed in the colony. The development of one of the most noteworthy battles between factions was known as the Ward – Hopkins political controversy. The noted political historian Jackson Turner Main stated: “Rhode Island produced the first two-party or more accurately two-faction system in America.” The leaders of the two factions were Samuel Ward of Westerly and Stephen Hopkins of Providence. Ward’s support came from the southern part of the colony with its center at Newport, whereas Hopkins’s support came mainly from the northern part of the colony with its center at Providence. Some of the issues and differences included taxes, debt, and paper currency. During the struggle between these two factions Hopkins was elected governor ten times and Ward three times. The controversy ended when both sides agreed on the same candidate (Josias Lyndon, who served as governor from May 1768 to May 1769) and both Ward and Hopkins retired as candidates. Ultimately Hopkins and Ward went on to represent Rhode Island in the Continental Congress.

This ticket was for the third Congress of 1792. Both Bourn and Malbone were elected at large (Collection of Daniel C. Schofield)

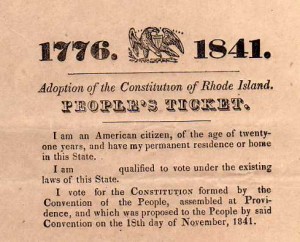

Rhode Island political factions did not end with the Ward–Hopkins period. During the War of 1812, Federalists battled Republicans; in the 1830s, an anti-Masonic faction emerged; and following the Dorr Rebellion of 1842, a Law and Order coalition made up of Whigs and conservative Democrats formed to counter the pro-suffrage movement. Special interest in elections continued into the 1850s with the advent of the temperance ticket. During the 1860s the pro-Union ticket formed, and by the 1870s and 1880s the Greenback party and the Prohibitory faction manifested themselves. It is an everyday fact of life that in a democracy politics will always be with us creating new factions.

In the early colonial years and before the use of printed ballots, freemen voted by voice in town meeting or, as already noted, on pieces of paper affixing their names to the back of the paper. Over time, political parties supplied the freemen with printed proxies. Because the freemen signed their names to the proxies, any secret vote was precluded. With any election came the possibility of fraud and abuse. Almost every election was preceded with a warning to the voters in the local newspapers of fraudulent election tickets being distributed to dupe the voters, and after almost every election the same newspapers carried accounts of stuffed ballot boxes or wholesale buying of votes by unscrupulous politicians. To curb these problems, the Rhode Island General Assembly passed a law at its March 29, 1889, session that effectively adopted an Australian type of secret ballot in envelopes. The first section of the law read:

In 1841 reformers led by Thomas W. Dorr held their own constitutional convention, the start of what was called the Dorr Rebellion. The ticket shown here was used as a ballot in an extra-legal election in December, 1841 (Collection of Russell J. DeSimone)

Section 1. All ballots cast in elections for electors of president and vice-president of the United States, representatives in congress of the United States, general officers of the state, and members of the general assembly, and all ballots upon any proposed amendment to the constitution of the state submitted to the electors for approval, after the first day of June, in the year eighteen hundred and eighty-nine, shall be printed and distributed at public expense, as hereafter provided. The printing of the ballots and instruction sheets, and the delivery of them to the several cities and towns, shall be paid for by the state. The distribution of the ballots to the voters shall be paid for by the cities and towns respectively.

With the passage of this law, the role of election tickets in Rhode Island ended except for their continued use in local elections. Numerous examples of these local tickets as they continued to be used throughout the 1890s and into the early part of the 20th century are known to exist.

These printed election artifacts are the subject of a recent study conducted by the authors. The study, while comprehensive, is not so complete as to represent every election ticket ever issued in Rhode Island during this period; however, with more than 670 tickets depicted showing individual images, measurements and brief descriptions, in addition to nearly another 1000 election tickets listed in the appendices of the study, it is an extensive look at the election process in 18th and 19th century Rhode Island. [3] The authors inspected and documented election tickets at the John Carter Brown Library, John Hay Library, Newport Historical Society, Providence City Archives, Providence Public Library’s Special Collections, Rhode Island Historical Society, Rhode Island State Archives, Warwick Historical Society, University of Rhode Island Library’s Special Collections as well as tickets in four private Rhode Island collections. In addition, Early American Imprints both Series I (Evans and Bristol) and Series II (Shaw and Shoemaker) were used. No other state is known to have conducted such an exhaustive study as that conducted for Rhode Island. A digital posting of this study is available on the University of Rhode Island’s Digital Commons webpage: http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/lib_ts_pubs/17/

[Banner image: a representative ticket for state presidential electors in the election of 1800. It marked the first time Rhode Island voters cast their choice for electors. During the first presidential election (1789) Rhode Island was not in the Union and in the elections of 1792 and 1796 the legislature selected electors (Collection of Russell DeSimone)]Footnotes:

[1]Howard M. Chapin, “Eighteenth Century Rhode Island Printed Proxies, p. 54-591 The Americana Collector; John E. Alden, Rhode Island Imprints 1727-1800 (New York: R.R. Bowker Co., 1949) x and 26. [2] It should be noted that Connecticut also used the term prox or proxy, which referred to an election or election day and not to the paper ballot. [3] There are four appendices in the study as follows: Appendix A – Tickets in the Rhode Island Historical Society; Appendix B – Tickets listed in Early American Imprints; Appendix C – Rhode Island Presidential Elector Tickets; and Appendix D – Proposed RI Constitutional Amendments and Other Referenda.