While Massachusetts and Connecticut by the early 1800s had instituted reforms reducing the severity of corporal punishment, Rhode Island had not. Consider the crime of perjury before a court. According to Rhode Island’s criminal code, a convicted individual was to be punished, in the discretion of the judge, with a variety of possible punishments, including standing four hours in the pillory, cropping of the ears, and/or branding with a hot iron.

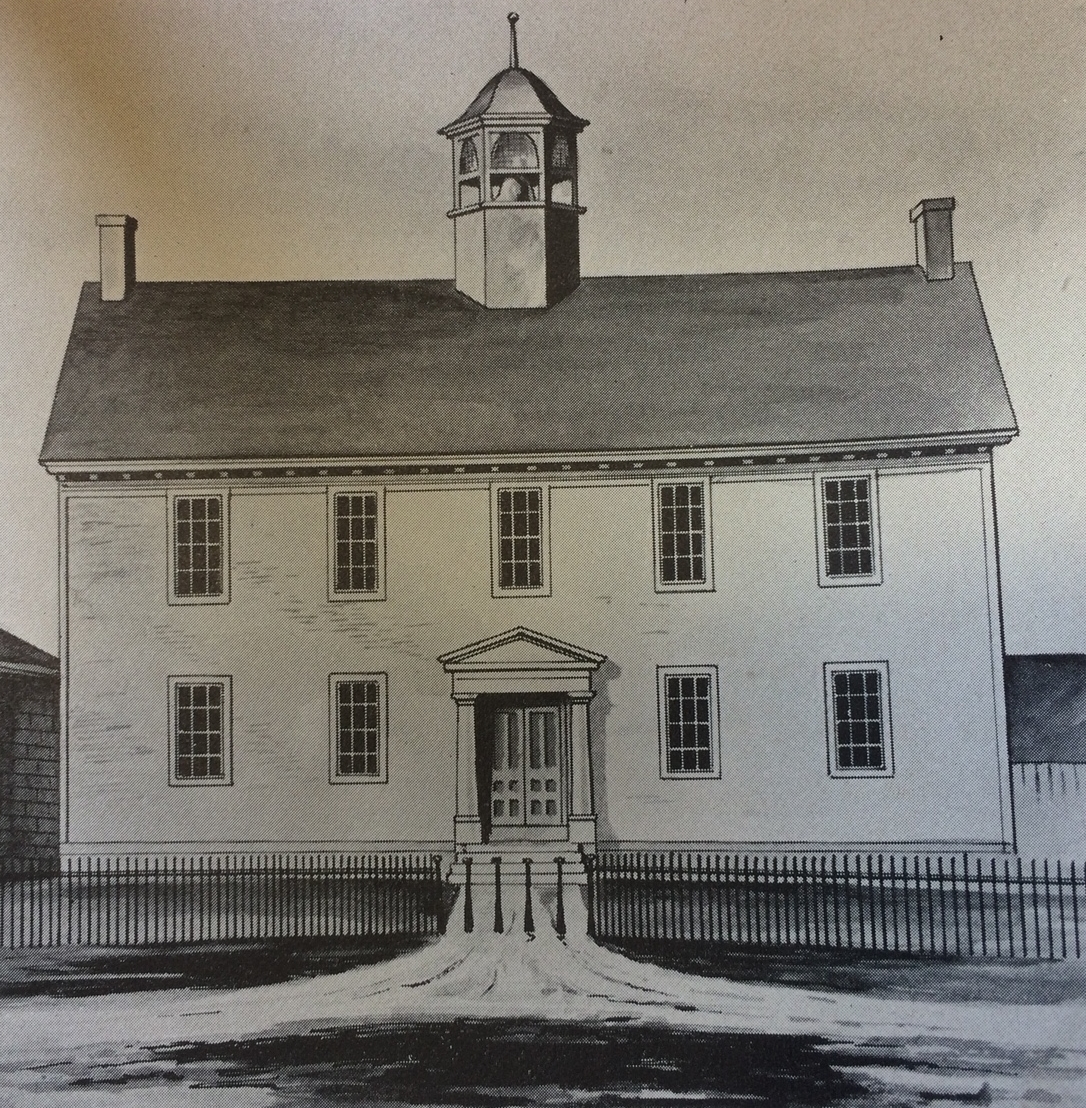

This article focuses on the Court House and County Jail at Little Rest (whose name was unfortunately changed to Kingston in 1825). The Court House and County Jail served Washington County. (The Court House now houses the Kingston Free Library and the last County Jail houses the South County History Center). Reform at the state level would change how punishment was imposed in Little Rest.

The Washington County Court House, by Henry Walling, 1857. The building looked much the same when it was built in 1776. The mansard roof the building now has was added in 1876. Jonathan P. Helme, who was born in Little Rest in 1809, recalled from his boyhood two times when the pillory was used in Little Rest, both times in front of the Court House. (Author’s Collection)

In the early 1800s, corporal punishment continued to be inflicted at Little Rest. A person found guilty of a petty theft crime typically was ordered to pay the victim money for losses suffered and to pay court costs. If the guilty person refused to or could not pay the amounts ordered, he or she would instead be subject to corporal punishment. For example, in 1796, in a justices court held in Little Rest, two white women, Mary and Rebecca Jones, were found guilty of stealing a few pewter plates, forks and knives. They were assessed fines to pay the victim, witness fees and court costs. If they failed to pay the assessed amounts, they were to “be whipped ten stripes each on the Naked Back.” They could not pay the money, so it appears they were whipped. Presumably, their clothing had to be taken off their tops, a further humiliation.

Sometimes, the crime was deemed so serious that the convicted criminal could not avoid whippings by payment of fines. For example, in 1791, in another justices court session in Little Rest, for the dual crimes of forging a court order and stealing a horse, Caleb Church was ordered to be whipped by the Washington County sheriff an equal number of times on a Wednesday, Friday and the following Monday.

Many of the prisoners who could not pay their fines and were therefore subject to corporal punishment were black. In 1801, Bristol Gardner, a black woman found guilty of theft, was whipped at the end of a cart through the streets of Little Rest. In the same year, Jacob Lewis was whipped. In 1802, Plato Babcock was found guilty of theft, served at least five months in jail, and was whipped by jailer Robert Helme, which according to Helme “paid his fine for stealing.” In 1807, Prince Watson, another black man, was convicted of theft; when he refused to or could not pay his fine of five dollars, he was whipped.

In the early 1800s, it appeared that crimes involving money and property were punished more harshly and were more likely to involve corporal punishment than violent crimes against persons. In 1808, George Northrop, a white man, was convicted of theft and whipped. In 1813, James Short, a white man convicted of forging a note, was sentenced to have a ‘piece of each of his ears cut off” while standing in the Little Rest pillory for an hour. In 1825, Palmer Hines of North Kingstown was convicted of setting fire to a barn filled with nine tons of hay, nine hogs and farming utensils. He was sentenced to pay a fine of $1,000, to be imprisoned in the Little Rest jail for four years, to have his ears cropped, and to be branded with the letter “R” (for Rogue). In 1823, William Bowen of Charlestown, for forging a $5 bank note, was imprisoned for six months in the Little Rest jail. In 1818, Thomas James of West Greenwich stole about $45 in cash and goods from Thomas Taylor’s general store in Little Rest. He was sentenced to six months in jail and to be whipped “39 stripes on the Naked Back.” In 1826, Benjamin Church stole only about $7 of gin and brandy from the Reynolds Tavern in Kingston, but was sentenced, in addition to repay the amount and court costs, to be imprisoned in the Kingston jail for two months.

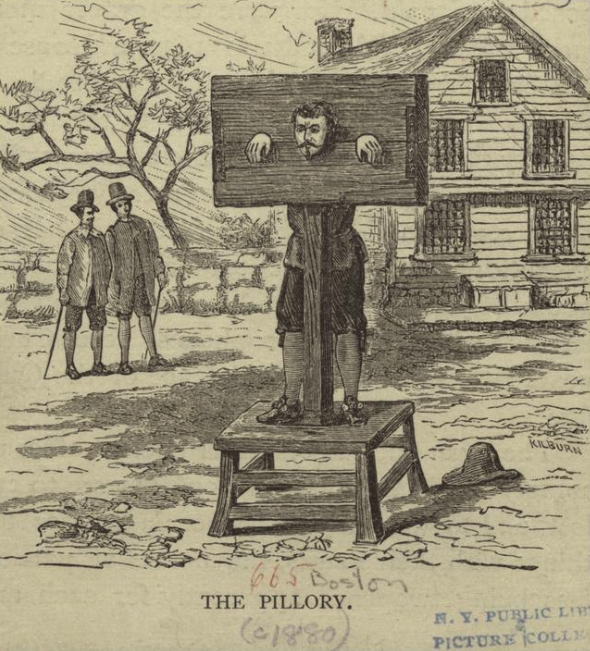

The use of a pillory for punishment for breaking the law in colonial times (New York Public Library Digital Collections)

By contrast, violent crimes against persons were not punished as harshly—at least in proportion to their crimes. In 1814, a South Kingstown white man who was convicted of burning and choking to death a five-year old girl, was sentenced to pay a fine of $2,000 and to be imprisoned for six years. In 1827, four Exeter residents were convicted of beating a four-month old infant to death, but each only received a six month prison sentence. In 1824, William Casey was convicted of beating and choking his wife, but he was sentenced only to remain in jail until his $30 fine and court costs were paid. In 1815, Jeremy Bradford stabbed a man with a knife, causing a four-inch gash, but was sentenced only to remain in jail until he paid a $50 fine and court costs. In 1825, two men who were convicted of beating a man “so that his Life [was] Greatly Dispaired of” received a sentence of only a fine and one month in jail.

It appears that in some instances the criminal law in this age cared more about property damage than criminally wounding or killing a human being. Perhaps part of that feeling was inspired by the thought of debtor’s prison that could result from the loss of property or money.

Jonathan P. Helme, who was born in Little Rest in 1809, recalled from his boyhood two times when the pillory was used in Little Rest. In one case, a convicted forger was sentenced to be cropped in the ears and branded while being held in the pillory in front of the Court House. Cropping entailed hacking off a piece of the victim’s ear. The sheriff carried out the sentence and, with blood running from his ears, the man was returned to the jail. In the second case, the victim was ordered to stand in the pillory for an hour. A crowd watched the punishment with “the boys throwing eggs, dirt, etc…, at the time he was exposed.”

Newspaper commentators began criticizing the use of whippings as inhumane in the 1820s, but it had no effect on the conservative law-and-order types These included Elisha R. Potter, Sr., a prominent politician and landowner from Little Rest (I grew up in his house). In 1822, the General Assembly appointed a committee of three men; including Potter, to undertake a revision of the criminal code, with a view, according to a newspaper, “of multiplying the cases in which the punishment of whipping, cropping, and branding may be inflicted.” This development caused alarm in neighboring Connecticut, where a New London newspaper lamented that Rhode Island “continues proof against the improvements of the age, and disgraces herself and the Union, by adhering to all these relics of feudal barbarism, not to be endured in a republic.” Even though Potter favored expanding the crimes in which corporal punishment could be inflicted, the majority of the committee favored simply limiting the discretion of the court in applying corporal punishment. Christopher Bickford, in his Crime, Punishment and the Washington County Jail, Hard Time in Kingston, Rhode Island, writes:

The problem for Potter, along with other law-and-order advocates, was his perception that the laws of Rhode Island were not being consistently applied. The apparent willingness of the Legislature to release convicts from jail and of judges to remit sentences of whipping, they thought, was breeding a disrespect for the law that they considered dangerous and unhealthy.

Part of the problem was that the state refused to create a single state penitentiary, a reform that had been adopted in many states. Until a proper prison was built to house prisoners on a long-term basis, corporal punishment would continue to be part of the penal system. When every prisoner in the Kingston jail broke out in January 1827, the Providence Daily Journal commented that “this is another proof of the necessity of erecting a states prison.”

Elisha R. Potter, Sr. became the most vociferous opponent of a state prison, mostly because he feared it would raise taxes on landowners like himself. In 1832, he stated bluntly that he was against the building of a state penitentiary and was “in favor of cropping, branding, and whipping.” Potter believed (with little evidence) that only one in fifty convicts was native born and that public whipping would drive off foreign rogues. When 1,600 Rhode Islanders presented a petition to the General Assembly protesting such mutilation of prisoners and the lumping together of prisoners in small county jails, and supporting the construction of a state prison, Potter responded that the petitioners paid little in taxes and that the funding for the state prison would have to come from banks and the land—in other words, the taxpayers of Washington County.

A heavy newspaper campaign and circulation of a detailed report in January 1834 favoring reform finally won over public opinion. In a referendum in April 1834, Rhode Island voters supported the construction of a state prison 4,433 to 502. In 1838, a new state prison, with forty cells, opened in Providence.

The General Assembly also enacted legislation reforming the criminal code in 1838. The three punishments included in the new code were “separate confinement in the state prison at labor, imprisonment in a county jail, and pecuniary fine.” As a committee report stated, “In substituting these for whipping, cropping, branding, and pillory, the committee believe they have carried out the intention of the General Assembly in the erection of a State Prison.” Under the code, all those sentenced to imprisonment for a period longer than one year were to be placed in the state prison, not the Kingston jail or any other county jail. Rather than hold those convicted of serious crimes such as murder and rape, the county courts would only hold those charged of such crimes until the trial had been completed. The list of capital crimes was reduced to murder and arson. (A committee had proposed that Rhode Island “try another experiment” and become the first state to abolish the death penalty entirely, but the proposal was narrowly defeated.)

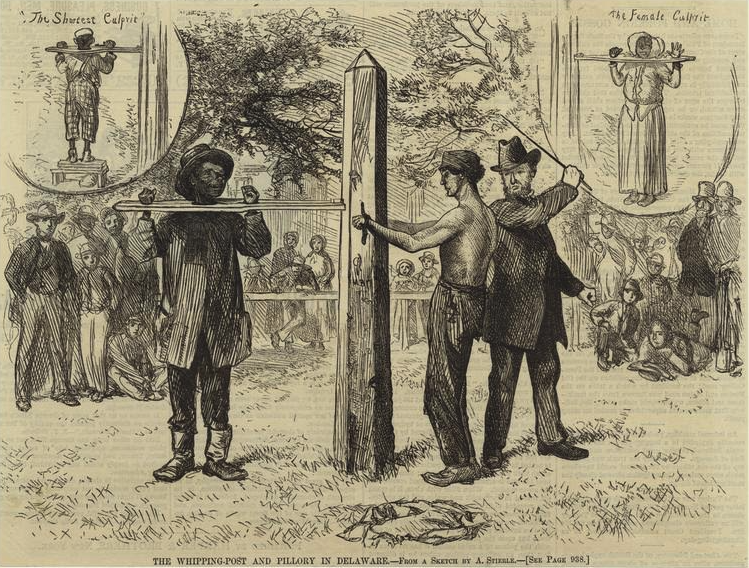

Showing a whipping post on the right, with a white man being whipped as punishment, and a pillory on the left, in Delaware. The use of the whipping post and pillory continued in Delaware into the 1900s (New York Public Library Digital Collections)

Those convicted of serious property crimes were no longer subject to corporal punishment or death sentences. For example, in 1851, two men who broke into a bank in Westerly and stole $15,400 in bank bills were sentenced to eight years in the state prison in Providence “at hard labor.”

One area that was not significantly reformed was imprisonment for debt. Much of the legal system in the county, starting from the local justices courts and ending in the jail in Kingston, was devoted to insuring that creditors were paid amounts owed to them. The sad story of many insolvent debtors is told in the hundreds of petitions for relief that jailed debtors submitted to the General Assembly, which granted only about half of them. In 1803, debtor John Phillips of Hopkinton said that he had spent a total of four years in jail, and in 1814 Simon Hazard of South Kingstown reported that he had been jailed three times for petty debts. On one occasion, the debt itself was only 48 cents but the jailer’s fees had raised it to $3.25.

Elisha R. Potter, Sr. did introduce and push through bills in 1830 in the General Assembly to exempt females from prison for debts, to forbid corporal punishment for debtors, and to abolish imprisonment for a debt of less than $5. But Potter led the opposition to passage of laws to abolish all imprisonment of debtors.

Historian Peter Coleman believes that reformers may have had difficulty rousing public opinion because the bankruptcy laws may have been viewed as being fairly lenient. For one, by posting a bond, jailed debtors had the “liberty of the yard” (the privilege of walking outside the jail cells) and could practice their crafts during the day. Debtors, generally had two options. First, they could take the “poor man’s oath,” which “Nailer Tom” Hazard traveled to Little Rest in 1822 to inquire about for his son. This approach forced the creditor to choose between releasing the debtor’s debts or holding him in jail at the creditor’s expense. Holding a debtor in jail gave the creditor revenge, but it was likely to cost him even more money. Alternatively, the debtor could petition for the benefit of the Act of June 1756, which required the debtor to make a full disclosure of his property, which was then distributed among creditors. If the debtor did not make an honest inventory, the General Assembly could send the debtor to prison until full disclosure was made. In Little Rest, Thomas Potter, the tavern keeper and merchant, in 1769, and Samuel Casey, the silversmith, in 1770, and William Lunt, the Revolutionary War pensioner and barber, in 1813, used this option. Debtors could also be released if they signed notes promising payment at a future date.

Jonathan Helme recollected two shocking (and perhaps exaggerated) examples of local residents who were imprisoned for debt by their creditors in the Washington County jail. In one case, the debtor was a storekeeper in a neighboring village who was jailed after his business failed. His creditors kept him in jail by paying the jailer one dollar a week. Helme stated that “His wife came to see him once a fortnight, bringing him clean clothes, and something to eat (as he had the liberty of the yard) and kept ‘old bachelor’s hall’ for more than fifteen years.” The man died not long after his release at to age of 76. In the other case, a Baptist minister was imprisoned for debt. He was a talented minister but had a weakness for rum and fell behind in his rent and grocery bills. Since he could not post a bond, he did not obtain the “liberty of the yard.” He was confined with others in one of the cells “in the common jail.” After his release from jail, another creditor sued him and sent him back to jail, “so that it was some time before the old minister could get home to his family or church.” Writing in 1874, Helme wrote that “there have been a great many attempts to eradicate this barbarous law from the statute book, but it has as yet only been modified.”

Daniel Stedman of Wakefield, in his journal in June 1832, noted that a local debating society debated the issue of whether imprisoning debtors should be abolished, and the consensus was that it should be abolished. Christopher Bickford found that the number of debtors in the county jails steadily decreased after the Civil War, but that the laws permitting imprisonment for debt remained on the books into the 20th century.

While the “warning out” of town of transients continued as a practice throughout the 19th century, there were some improvements in the harsh treatment of the poor. By around 1810, the practice of jailing adults who were the parents of illegitimate children had ceased. By the 1830s and 1840s, many towns, including South Kingstown, had “town farms” that housed the poor. The town farms provided shelter, food, clothing and work. While town farms were sometimes subject to severe rules, they were more humane than the system of “binding out” poor persons who were town charges to strangers.

Peace Dale’s Thomas R. Hazard, the author of The Jonny-Cake Papers, was the state’s most important reformer of the poor laws. In a shocking report in 1850, he criticized the continuing use of “binding out” town charges, which had not been completely abolished in Rhode Island towns. He bluntly stated that Rhode Islanders would not put out their cattle as they let out their poor. He explained the benefits of town farms and asylums. He recommended the abolition of dark rooms, dungeons, chains, and corporal punishment in dealing with the poor, which the. General Assembly quickly did.

In 1847, the Butler Asylum for the insane was opened in Providence due to the gifts of many benefactors, including the Hazard brothers of Peace Dale. Beginning in 1855, the South Kingstown Town Council began paying the hospital for caring for a few townspersons.

Sources:

This article is based on a chapter that appeared in Christian McBurney, A History of Kingston, R.I., 1700-1900, Heart of Rural South County (Pettaquamscutt Historical Society, 2004) (currently on sale at Wakefield Books and Picture This).

This article relies heavily on Bickford, Christopher, Crime, Punishment and the Washington County Jail, Hard Time at Kingston, Rhode Island (Pettasquamscutt Historical Society, 2002), 31-38 & 46-49; see also Brennan, Joseph, Social Conditions in Industrial Rhode Island, 1820-1860 (The Catholic University of America, 1940), 144-49.

For the sentences of whipping in default of paying fines, see in South Kingstown Town Hall the South Kingstown Justices Court Records, 1796-1806, Cyrus French, Justice, Dec. 6, 1796 (Mary and Rebecca Jones defendants; for stealing two plates; ten lashes each on the “Naked Back” if fines not paid); South Kingstown Justices Court Records, 1793-98, Levi Totten, Justice, May 20, 1794, 28-30 (Peter Freeman, a “molatto,” for stealing small items including a linen handkerchief; thirty lashes on his “Naked Back” if fines not paid). Mary and Rebecca Jones may have been whipped, as they were not able to pay all of the court costs. The General Assembly ended up paying fees to justices and sheriffs handling the case and witness fees. Rhode Island Acts and Resolves, Oct. 1797 Session, v. III, 25.

For the whipping sentence for Caleb Church, see Rhode Island Acts & Resolves, June 1791 Session, v. I, 22-23.

For crimes involving money and property, see in the Rhode Island Judicial Archives in the Washington County Superior Court Records, Oct. Sess. 148-19 (Short); Oct. 1825 Sess. 581-82 (Hines); April 1823 Sess. 418-20 (Bowen) April 1818 Sess. 69-71 (James); Oct. 1826 Sess. 607 (Church).

For violent crimes, see ibid., April 1814 Sess. 166-69 (five-year old victim); April 1827 Sess. 666-71 (four-month old victim); April 1824 Sess. 469-70 (Casey); April 1815 Sess. 230; Oct. 1825 Sess. 583 (“Life … Greatly Despaired of”).

For the background on the debtor laws, see Coleman, Peter, J., The Transformation of Rhode Island, 254; Coleman, Peter J., “The Insolvent Debtor in Rhode Island, 1745-1828,” William & Mary Quarterly 22: 413, 429 (1965) (J. Philips and S. Hazard); Brennan, Joseph, Social Conditions in Industrial Rhode Island, 144-45.

For Helmes’s anecdotes, see Helme, Jonathan, Recollections of South Kingstown,” manuscript at Kingston Free Library. Helme did not cite these anecdotes in the version of his reminiscences that appeared in the Providence Journal on October 31, 1874. He wrote that the first instance of corporal punishment was for counterfeiting, but he probably meant forging. Criminals had turned from counterfeiting bills and coins in the 18th century to forging bank notes and promissory notes in the early 1800s. The victim could also have been Palmer Hines of North Kingstown; who in 1825 was convicted of setting fire to a barn filled with nine tons of hay, nine hogs and fanning utensils. He was sentenced to pay a fine of $1,000, to be imprisoned in the. Little Rest jail for four years; to have his ears cropped, and to be branded– with the letter “R.”

For the 1851 bank theft case, see in the Rhode Island Judicial Archives the Washington County Superior Court Records, Feb. 1851 Sess. 630-35 (State v. John Collins; State v. Henry Dasey).

For Thomas Potter petitioning the General Assembly for relief under the Act of 1756, see in the Rhode Island Judicial Archives the King’s County Superior Court Records, Nov. 1768 Sess. 229.

For Samuel Casey’s petition of insolvency to the General Assembly, see Petitions to the General Assembly 1770-72, No. 9, Rhode Island State Archives.

For William Lunt’s insolvency, see in the Rhode Island Judicial Archives the Washington Court Supreme Court Records, April 1813 Sess. 122.

For Potter’s support of the bills for minor relief of debtors, see Providence Journal, Jan. 15-16, 1830 & June 21, 1830. For Potter’s opposition to debtor relief, see also Field, Edward (ed.), State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations (Mason, 1902), vol. I, 314.

For Hazard’s journal entry; see Hazard, Caroline, Nailer Tom’s Diary (Merrymount Press, 1930), 587 (Nov. 11, 1822).

For Stedman’s journal entry, see Oatley, Henry Clay, Jr. (ed.), Daniel Stedman’s Journal, 1826-1859 (Rhode Island Genealogical Society, 2003), 112. In October 1793, the General Assembly voted “that the Liberties of the Gaol-Yard in the County of Washington by extended so far Eastward as to allow the Prisoners who have the Liberty thereof to pass into the State-House in the aforesaid County.” Rhode Island Acts & Resolves, Oct. 1793 Session, v. I, 20. In 1811, a debtor held in the Little Rest jail, James Rose, did “break the wall of the said jail and then removed a piece of plank and made his escape.” Washington County Supreme Court ‘Records, 1811 Sess., 84-85.

For Thomas Hazard and his movement to improve the treatment of poor persons, see Brennan, Joseph, Social Conditions in Industrial Rhode Island, 142-44.

For the use of Butler Asylum, see in the South Kingstown Town Hall the South Kingstown Town Council Records, v. 8, 132 (Nov. 1, 1855 meeting).