The 17th century brought enormous changes to the Western Hemisphere, commonly called the Americas. European explorers and settlers claimed land in North and South America for economic, sovereignty, political or religious reasons. But the common bond between them was the use of enslaved Africans as the chief labor force to clear land, build cities and harvest the cash crops that would make men and communities wealthy beyond imagination. The introduction of African bondage was a transformative experience that lasted over a span of four centuries and shaped the settlement, economic, religious and cultural growth of the Western Hemisphere.

What stands out about the enslavement of African people in the Americas as compared to slavery throughout world history is the unique concept of confining slavery to a single race and that children of enslaved mothers were born into slavery to serve for the remainder of their lives. This brutal system of inheritable servitude impacted the lives of tens of millions of displaced Africans and dramatically shaped the settlement and formation of the Americas.

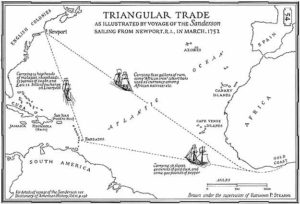

Map showing the voyage of the slave ship The Sanderson, sailing from Newport, RI, in March 1752 (Raymond Stearns)

It is important to note that while slavery was long established on the African continent, it was not the race based and transferable condition that was uniquely established in the Americas. Slavery in the Americas was also uniquely characterized by active participation of most European countries in search of land, conquest, settlement, colonies, and economic exploitation.

Those honored men, women and families that first settled in Rhode Island nearly four centuries ago, brought with them to these shores an unconquerable sense of religious toleration. As persecuted religious minorities, they built not only a new home, but create a place where anyone, regardless of religious bearings, could settle and prosper. But Rhode Island during those early years also embodied a distinct irony: while Rhode Island was founded on the principles of religious freedom and civil liberties, its people developed into the leading slave traders of any of the British thirteen colonies in North America.

As Rhode Island colonists prepared to go to war with Great Britain over taxation without representation, these same colonists enjoyed, directly and indirectly, economic prosperity through enslaved African labor.

“If you say you have the right to enslave (Negroes) because it is for your interest, why do you dispute the legality of Great Britain’s enslaving you?”

– A True Son of Liberty, Newport Mercury, January 8, 1768

Only a small fraction of the estimated ten million enslaved Africans brought to the New World in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries end up in British North America. The vast majority of African captives were shipped to South America (particularly Brazil) and the Caribbean islands. The first of these “forced immigrants” arrived in the Colony of Rhode Island sometime around 1652 and the first documented slave ship, the Sea Flower, arrived in Newport in 1696. The Rhode Island Black Heritage Society, in a comprehensive assessment of early Black history in Rhode Island, noted, “The Slave Trade Empire in Rhode Island began sometime around the latter part of the 17th century and slavery grew under the auxiliary enterprise of barrel-making, molasses and rum.”[1]

The African Slave Trade and Rhode Island share common origins. Newport, for example, one of the most prosperous seaports in British North America, experienced unprecedented growth during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, mostly through the production and export of rum, spermaceti candles, cod fish, and enslaved persons. Many of the enslaved Africans who arrived in Newport originated from the Guinea, Gold and Cape Coasts of West Africa. Many also came to Newport from West Africa via the British Caribbean islands of Barbados and Jamaica. By the middle of the eighteenth century, the population of Africans in Newport reached 17 percent of the total population; most of them were enslaved but some were free persons.[2]

From a series of letters between Jewish merchants based in Newport, Aaron Lopez and Jacob Rodriquez Rivera, and their ship captain William English, a vivid account of the deep connections between colonial Rhode Island, the Caribbean and West Africa is revealed. The letters show the transatlantic trade between Newport, Gold Coast, Jamaica and eventually back to Newport. An example is this letter, from Captain William English, then at the coastal West African slave trading town at Anamaboe (now called Anomabu), dated July 15, 1773, to Aaron Lopez and Jacob Rodriquez Rivera of Newport:

I have enclosed you Bill of Landing for 30 slaves. I hope you will not take amiss my leaving these 10 slaves behind as my provisions expends fast and I am afraid of sickness getting among the slaves I have on board. The few slaves I have is very good and healthy at present, and have not lost 1 slave yet. Thank God for it.[3]

The peculiar institution of slavery had its start and evolution with the sea. And in colonial Rhode Island one of the best paths for African freedom and prosperity led back to the sea. Early American maritime industry was a meritocracy. Crew were hired based on their skill and ability, not on race. In his award winning book on African American seamen, W. Jeffery Bolster points out that seafaring was one of the most significant occupations among both enslaved and free African heritage men in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.[4] In his ground-breaking study of the slave trade in Rhode Island, Jay Coughtry estimated that African heritage seaman comprised up to 21% of Newport crews engaged in Caribbean, European and African voyages.[5] Ironically, this significant percentage of African heritage mariners, particularly from Newport, created a troubling situation when they served on slave ships, as explained below.

By way of historical practicality, the use of African mariners on slave vessels, notably those travelling from the African Coast to the Caribbean, was directly related to the sickness and mortality rate of white crewmen. The trans-Atlantic slave trade voyage at the time was commonly referred to as the “white man’s grave,” due to lack of resistance to African and Caribbean diseases such as Yellow Fever. The use of African crew members who were already exposed and resistant to these diseases, protected not only the stability of the crew, but ensured completion and profitability of the slave voyage.[6]

This concern for African crew participation in the trans-Atlantic slave trade became a significant concern for a group of free Africans in eighteenth-century Newport. During much of the eighteenth century, Newport was a major American slave port and a substantial part of the town’s residents were enslaved Africans. Between 1705 and 1805, Rhode Island merchants at Newport, Bristol and Providence sponsored over 900 slave voyages to West Africa, with Newport merchants accounting for over 600 of those voyages.[7]

Rhode Island slave merchants, particularly in Newport, specialized in bartering with African agents along the African coast, where slave prices were cheaper than larger slave markets on the coast. Enslaved Africans were purchased directly from African go-betweens rather than the traditional European middleman. The “Black Trade” as it was known became a major issue to address within the Free African community in Newport. Fort William at Anomabo along the Gold Coast was the most active African slave port in British North America, and Newport was by far the most important slave port in the British North American colonies. The Rhode Island merchants were a fixture at Anomabo; a 1770 list of ships at anchor at Fort William included fourteen vessels, most from Rhode Island.[8]

Quaker Joseph Wanton, governor of the colony of Rhode Island from 1769 to 1775, like many Newport merchants, was an active participate in the slave trade at Anomabo. In the following passage, he admits his participation in the slave trade to the Quaker meeting:

I Joseph Wanton, being one people called Quakers and conscientiously scrupulous about taking an oath upon solemn affirmation, say that on the 1st day of the month commonly called April A.D. 1758 I sailed from Newport in the Snow, King of Prussia, with a cargo of 124 hogsheads of rum, 20 barrels of rum, and other cargo; that on the 20th day of May, I made Cape Mount of the west coast of Africa; that I ran down the coast and traded until I arrived at Anuunabibo [Anomabo], where, while at anchor, on the 23 day of the month called July, when I had on board 54 slaves.[9]

Ironically, many Rhode Island slave merchant ships active in the trans-Atlantic slave trade had on board some African heritage crew members who became actively complicit in the trading of fellow Africans. This was evidenced by the 130-ton brigantine, Prince George, which sailed out of Newport in 1758 for the West African Coast and transported 151 enslaved Africans from the Gold Coast to Barbados. Participating on the ship’s voyage were African heritage crew members Joseph Hull, Cuff Godfrey, Prince Lillibridge, Negro Amas, James Tosh and Thomas Atwood’s “Negro Scipio.”[10]

The use and benefit of having African heritage crew members on slave voyages served more than the added disease resistant manpower to operate the vessel. African crew members also acted as translators aboard slave ships with a keen knowledge of coastal locations and logistics.

As early as 1780, free Africans in Newport had assembled and established the Free African Union Society for the purpose of promoting, preserving and protecting African rights in Newport and America. This self-help African organizational concept later extended to New York, Philadelphia, Boston and Providence, Rhode Island. On October 6, 1791, the Newport group composed and forwarded a letter to other African organizations opining that Africans who participated in the slave trade would not be welcome as members of their societies. While there are no extant Newport records of Africans denied or expelled from membership because of slave trade participation, the fact the formal notice was drafted and publically conveyed provides a glimpse into the real concerns and the complexity of human relations during the early formation of America and our shared, and often tragic, past.

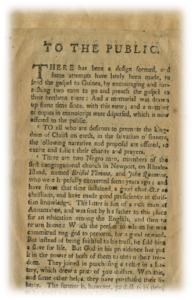

Plea to raise funds to send volunteers John Quamino and Bristol Yamma from Newport back to Africa (courtesy of Rhode Island Black Heritage Society)

Be it Remembered, and it is hereby made known to all whom it may concern, that the Africans, the Natives of Africa, residing in Newport, we the committee of the African Union Society, taking into consideration, thought it our indispensable duty not to associate ourselves to those who are of the African race that do, or hereafter be the means of bringing, from their Native Country, the males, females, boys & girls from Africa into bondage, etc. that hurt of themselves and the Inhabitants of the country or place where they may be bought and sold, and that we the said Committee, for ourselves and the Members of the said Union Society, whom we represent, will not, directly or indirectly, receive any of our acquaintances, Fathers, brothers or other relations into this Society, who is or shall be the means of bringing into slavery or bondage, any of their nation, or others being Africans or Natives thereof, the Natives that are commonly called by Inhabitants in Newport, Negroes, & the Inhabitants of the United States of America in general. Whereas at the last Meeting of the present committee, it was proposed that it was not right & just to encourage those blacks who were the means of bringing or transporting from Africa into this country the natives of Africa or elsewhere to make slaves, to the great hurt of the Inhabitants of any part residing there in said places, that those who were guilty of such acts, being blacks, should not enter into this Society as members thereof, that so long as they were guilty, or did persist in said trade, should not enter into said Society, nor be entitled to the privileges & advantages that any other Member might be benefited thereby, this being a rule of the present committee. At a meeting of the committee of the African Union Society, held in Newport and on the first Thursday evening of October, being the sixth day of said month, Anno Domini, 1791, at Mr. John Green’s.[11]

African heritage men also served within the maritime industry as a means to raise money for the purchase of their enslaved families. Free African John Quamino was born around 1740 in the coastal town of Anomabo on the West African Coast. The name Quamino or Quamine is the English phoneticized pronunciation of the name Kwame used by the Akan people of the Gold Coast from the tradition of providing the day name for boys born on Saturday. John Quamino arrived in Newport around 1754. Several historical accounts describe his father as a prominent member of his tribe who entrusted his son to a white slave merchant to be brought to America for education; but that John was unscrupulously sold to a Benjamin Church of Rhode Island and enslaved. While enslaved in Newport, Quamino was trained as a barrel maker and had access both to education and religion. He became an active member of Newport’s First Congregational Church. In 1773, Quamino purchased his freedom from the proceeds of a town lottery. Later that year, his life radically changed through an inventive plan conceived by two of Newport’s leading ministers.

That same year, Reverend Samuel Hopkins of the First Congregational Church and Ezra Stiles Newport’s Second Congregational Church, collaborated on a plan to send two African men back to Africa to promote the Christian religion and begin to evangelize the continent. They secured two volunteers, Quamino and a Bristol Yamma, both of whom were sent to study at the College of New Jersey (today’s Princeton University) under President John Witherspoon. A circular letter made available to the public sent by Hopkins and Stiles from Newport on August 31, 1773 stated:

There has been a design formed, and some attempts have lately been made, to send the gospel to Guinea, by encouraging and furnishing two men to go and preach the gospel to their brethren there. And a memorial was drawn up some time since with this view, and a number of copies in manuscript were dispersed, which is now offered to the public.

To all who are desirous to promote the kingdom of Christ on earth, in the salvation of sinners, the following narrative and proposal are offered, to excite and solicit their charity and prayers.

There are two Negro men, members of the first congregational church in Newport, on Rhode-Island, named Bristol Yamma, and John Quamine, who were hopefully converted some years ago, and have from that time sustained a good character as Christians, and have made good proficiency in Christian knowledge. The latter is son of a rich man in Anamaboe [Anamabo], and was sent by his father to this place for an education among the English, and then to return home. Which the person to whom he was committed engaged to perform, for a good reward. But instead of being faithful to his trust, he sold him as a slave for life. But God in his providence has put it in the power of both of them to obtain their freedom. They joined in purchasing a ticket in a lottery, which drew a prize of 300 dollars. With this, and some other helps, they have purchased their liberty. The former is however, fifty dollars in debt, as he could not purchase his freedom [for] under 200 [dollars]; which he must procure by his labor, unless relieved by the charity of others.

These persons, thus acquainted with Christianity, and apparently devoted to the service of Christ, are about thirty years old, have good natural abilities, are apt, steady and judicious, and speak their native language, the language of a numerous, potent nation in Guinea, to which they both belong. They are not only willing, but very desirous to quit all worldly prospects and risk their lives, in attempting to open a door for the propagation of Christianity among their poor, ignorant, perishing, heathen brethren.

The concurrence of all these things has led to set on foot a proposal to send them to Africa, to preach the gospel there, if upon trial they shall appear in any good measure qualified for this business. In order to this they must be put to school, and taught to read and write better than they now can ; and be instructed more fully in divinity, &c. And if, upon trial, they appear to make good proficiency; and shall be thought by competent judges to be fit for such a mission, it is not doubted that many may be procured, sufficient to carry the design into execution. What is now wanted and asked, is money to pay the debt mentioned, and to support them at school to make the trial, whether they may be fitted for the proposed mission.[13]

Both Quamino and Yamma did not complete their education, as the plan to send them to Africa was disrupted with the start of the American Revolution in April 1775. It must have been a bitter realization for them that they would not soon return to Africa. For Quamino, and as with many of his fellow African brethren, the sea was a fast means to earn money to purchase the freedom of his wife and children. He enlisted in a crew for an American privateer vessel, whose crew would share in any captures. But Quamino was killed at sea serving on board the American privateer during the early days of the war, giving his life in service to a fledging America that continued to uphold the brutal practice of African heritage bondage.[14]

One existing historic site that is also an invaluable repository of information on African heritage mariners is the “God’s Little Acre” section of Newport’s Common Burying Ground. Recognized as having perhaps the largest and oldest collection of markers of enslaved and free Africans from the colonial American era, many existing markers document mariners. For example, leading Newport merchant John Bannister frequently recorded the use of enslaved and free Africans in his ship journals, including Fortune Cahoon, Quash Dunbar, and Hercules Brown, all buried within God’s Little Acre.[15] The burial marker in God’s Little Acre for Adam Miller indicates that he was a mariner who died at sea in 1799.

The gravestone in “God’s Little Acre” in Newport states, “Adam Miller, who died at sea, 1799, aged 43 years ….”

Many enslaved Africans chose the path to freedom as runaways through the sea. In reviewing runaway slave advertisements of the time, there are a significant number of enslaved servants who escaped from one slave community to “hide in plain sight” within other New England coastal urban centers. This logical action found enslaved Africans fleeing from New London or Boston to live relatively free lives in, say, New Bedford, Newport and Providence; many of these escapees joined crews on sailing vessels. African heritage crew members served in every capacity aboard vessels; they often started as cooks and cabin boys and often times were promoted to able-bodied seamen.

Enslaved and free Africans, through their keen intellect and seamanship, found many paths to living productive and fulfilling lives, despite the harsh restrictions of the slave institution in early New England. In colonial Rhode Island one of the best paths for African heritage men seeking freedom and then prosperity led back to the sea. Their story is one of resiliency, perseverance and “creative survival.”[16]

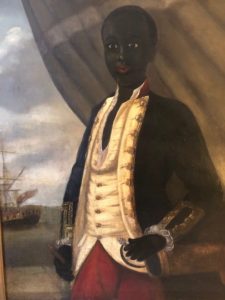

While the face of the sailor was found to have been painted in the 1970s, the image still represents the many African heritage mariners who worked at sea from Rhode Island and other coastal communities during the 18th and 19th centuries (Christian McBurney)

[Banner image: Fort William at Anomabo in Ghana, formerly a slave trading post (Keith Stokes)]

Notes:

[1] Rhode Island Black Heritage Society, A Heritage Discovered: Blacks in Rhode Island (1984), p. 5. [2] William Dillon Piersen, Black Yankees: The Development of an Afro-American Subculture in Eighteenth-Century New England (University of Massachusetts Press, 1988), p. 15. [3] Quoted in Bulletin of the Newport Historical Society, vol. 66 (July 1927), p. 23. [4] W. Jeffery Bolster, Black Jacks: African American Seaman in the Age of Sail (Harvard University Press, 1988), pp. 5-6. [5] Jay Coughtry, The Notorious Triangle: Rhode Island and the African Slave Trade, 1700-1806 (Temple University Press, 1981), p. 60. [6] Ibid., p. 154. [7] Ibid., pp. 239-285. [8] Randy J. Sparks, Where the Negroes Are Masters, An African Port in the Era of the Slave Trade (Harvard University Press, 2014), p. 165 [9] William P. Sheffield, Privateersmen of Newport, An Address before the Rhode Island Historical Society (John P. Sanborn Printer, 1883), pp.28-29. [10] Quoted in ibid. pp.28-29. [11] Brigantine George, 1757-1782 Privateer of War, Christopher Champlin Papers, Microfilm, E445, Reel 1-9, Rhode Island Historical Society. [12] Records of the Free African Union Society, Newport Historical Society. [13] Reverend Samuel Hopkins, Memoirs of the life of Mrs. Sarah Osborn (N. Elliot Bookseller, 1814), pp. 78-80. [14] Piersen, Black Yankees, p. 58. [15] Marian Desrosiers, John Bannister of Newport, The Life and Accounts of a Colonial Merchant (McFarland, 2017), p. 92. [16] The term “Creative Survival” was coined by the Rhode Island Black Heritage Society in 1984 in an exhibit on the Providence black community in the nineteenth century.